CHAPTER XI

The "Slander Campaign"

British experience in two world wars had indicated that any women's service soon after organization would become the target of slanderous charges, which would lower morale, alarm parents, and make it impossible to secure a large corps except by drafting women. However, the WAAC had appeared to be relatively free of such charges during its first few months. It was therefore prematurely hoped that the American public had, since the early attacks on the Army Nurse Corps, outgrown the use of moral charges as a means of opposition to women in public life.

Record of the WAAC's First Year

This hope was sustained by the fact that the Corps' record, as it reached the milestone of its first birthday in May of 1943, remained good beyond even the highest expectations. Recruiting, training, and supply difficulties had had little if any effect upon the efficiency of WAAC units in the field. The War Department, which had supported military status in advance of proof of WAAC efficiency, now found its action justified by all field reports. From North Africa, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower's headquarters expressed enthusiasm for the performance of the first WAAC company and forwarded requests for hundreds more enlisted women, without whom, it was declared, it was "literally impossible to conduct effective administration." The theater requested that these units "be given earliest priority . . . and shipped at expense of ground force replacements." 1 Equally important for public opinion, both health and discipline in North Africa had been good, and there had been only one pregnancy, that of a married woman.

From the secret antiaircraft artillery experiment, which was concluded about this time, came an official report that Waacs could fill more than half of the jobs in AAA units, and were "superior to men" in many operations requiring dexterity.2 War Department files abounded in reports of sudden conversion, such as that of the post commander who informed Col. Frank U. McCoskrie that Waacs would be sent to his post only "over my dead body," but who, a few months after their arrival, was discovered to be not only alive but writing to Des Moines for two more companies.3 From other station commanders came similar indorsement.4 The commanding general of a port of embarkation wrote, "I am greatly impressed with their discipline, intelligence, efficiency, and devotion to

[191]

duty. They have raised the standard of discipline of the command." Similar comment was received from the Signal Corps, Air Forces, Adjutant General's Department, and service commands, respectively: "Proved its value in hundreds of departments"; "Their work is splendid"; "looking forward to receiving more Waacs"; "highest type of intelligence and aptitude"; and so on.5

An Army Service Forces inspector in May of 1943 reported, after a visit to Waacs in the field:

My impression in general of WAAC personnel is:

1. They are doing a fine job in the training center . . . .

2. They are performing the jobs to which assigned . . . in an excellent

manner.

3. The officers and enlisted personnel with whom the Waacs work are more than

satisfied with the efficiency and manner in which the women perform their tasks,

as well as their attention to military courtesy.

4. The WAAC personnel is happy and doing a fine job.

5. The conduct of the WAAC personnel both on the job and after working hours is

satisfactory . . . . The using people heartily endorse the use of Waacs and want

to know when they are going to get more.6

Remarks of service commanders at a conference in July of 1943 likewise indicated that they were unanimously satisfied with their WAAC personnel and had experienced no noteworthy difficulties except in recruiting.7

A newspaper commented in July, near the first anniversary of the Des Moines

school:

The life history of the Waacs reads like the proverbial American success story.

At their inception they were offered a chance to make good at only a handful of

noncombatant jobs then considered suitable for women. Within little more than a

year they had proved so effective that the Army now urgently asks that their

ranks be increased to 600,000.8

In the summer of 1942 only four jobs had been authorized for Waacs; in the summer of 1943 Waacs were already filling 155 different Army jobs, and the number was increasing daily. In 1942 it had not been supposed that the WAAC's range of usefulness would require assignment other than to the Army Service Forces; in mid-1943 Waacs were already assigned to every major Army command in the United States and to two active overseas theaters; they were stationed in forty-four of the forty-eight states. In 1942 the admission of women even to auxiliary status appeared risky; in 1943 the War Department entertained no further doubts about the wisdom of full integration of women into the Army.9

General Somervell noted, in commending General Faith, "The excellent discipline, military courtesy, and appearance of the Women's Army Corps . . . are equalled by few and surpassed by no other group in the Armed Services." 10

Statistical records in May of 1943 showed that, in spite of the brief lapse in recruiting standards, Waacs still surpassed in qualifications both the civilian average and that of Army men. The "average" Waac at this time was a mature woman, 25 to 27 years old, healthy, single, and without dependents. She was a high school graduate with some clerical experience. According to information derived from

[192]

psychiatrists' interviews, she was inspired to enter the WAAC chiefly by a desire to do war work of a more active and responsible nature than was generally possible to a woman in civilian life. Of the small number of her eligible American sisters who were similarly inspired to the extent of getting an application blank, she was the one in three who completed it, after which she had survived tests and interviews that eliminated half of her fellow applicants. Before shipment to her job in the field, she had cost the Army only four weeks of basic training but no specialist training, which had not, for the average woman, proved necessary to successful assignment. On the men's AGCT test, she made an average score of 109. At her field station, she accepted assignment to routine clerical work although she would have liked to drive a truck. She had not yet been promoted, and her rank remained that of auxiliary (private), at $50 a month.11 She constituted a permanent and reliable type of employee, not being subject to transfer to combat duty, nor to the usual causes of turnover in civilian personnel.

From the public viewpoint the Corps' moral record was even more important than its job efficiency. Statistical records indicated that, even with the brief lapse in standards during February and March, enlisted women's morality exceeded the civilian average. The WAAC rate of venereal disease was almost zero; many WAAC units had not experienced a single case, while training centers generally encountered only cases that had been undetected by faulty enlistment examinations. Even including cases existing before enlistment, the incidence in the WAAC was far below that of either the Army or of women in civilian life. As for pregnancy among unmarried women, the rate in the WAAC was about one fifth that among women in civilian life. This record was even better than that reported in 1942 by the British women's services, which was itself better than that of British civilian women.12

However, by May of 1943 it was already known within the War Department that the American corps, in spite of its actual record, was not to escape the traditional fate of slanderous attack, which became familiarly known to the Department's investigators as the "Slander Campaign," sometimes also called the "Whispering Campaign" or "Rumor Campaign." The slander campaign was, as its name implied; an onslaught of gossip, jokes, slander, and obscenity about the WAAC, which swept along the Eastern seaboard in the spring of 1943, penetrated to many other sections of the country, and finally broke into the open and was recognized in June, after which the WAAC and the Army engaged it in a battle that lasted all summer and well into the next year before it was even partially subdued.

It was WAAC Headquarters' belief at the time that full and early publicity on the record of the WAAC's first year might have prevented what followed. However, during the period when the slander campaign took shape and gained momentum, it was the policy of the War Department

[193]

Bureau of Public Relations to permit no specialized attention to the WAAC. There was no central agency charged with securing and releasing the true record and statistics of the Corps' first year; news stories on WAAC life were generally limited to those; which news media secured and presented for clearance. The Bureau's Radio, Press, Pictorial, and Publications Branches all handled WAAC news releases separately and without co-ordination of policy.

General Marshall and others evidently supposed that there existed some central publicity group for the support of recruiting; as late as January of 1944 General Marshall addressed a memorandum to the "WAC Recruiting Section, Bureau of Public Relations," although there was actually no such agency.13

To make up for the lack of a publicity campaign from the Bureau of Public Relations, the Director attempted to bring enough WAAC public relations personnel into her own office to supply good material to news media and guide them toward desired policies. For this purpose, she was allowed a small Office of Technical Information (OTI), such as other administrative services had, chiefly designed to check releases for technical inaccuracies but not to promote publicity. In the WAAC's first months the Director requested a larger allotment for this office, on the grounds that the WAAC must recruit personnel and was the object of more "extraordinary public interest'" than other administrative services. The Services of Supply refused this request on the grounds that men's organizations, such as the Chemical Warfare Service, did not have a larger allotment.

Even had more personnel been allotted it, the WAAC OTI was not allowed by the Bureau of Public Relations to handle publicity. In April of 1943, the OTI appealed to the bureau for permission to contact editors directly to get more accurate and positive articles in magazines and journals, since the "personnel shortage" in the bureau had apparently made it impossible for that agency to achieve the desired results. In reply, the Bureau of Public Relations published a directive that all inquiries concerning the WAAC received by WAAC Headquarters would be referred to the Bureau of Public Relations, and that inquiries received by the bureau would be handled by it without reference to the WAAC except by telephone.

The extent to which the WAAC OTI was allowed to influence the bureau's decisions was limited; in June, General Surles reminded the Director by personal letter that when his Review Branch asked any OTI for comment, it desired only views on security and accuracy, and not opinions on method of presentation or tone.14 Projects originated by the WAAC were frowned upon; thus, when the Director desired to use the WAAC Band on a radio program, the bureau vetoed the idea on the grounds that "publicity is moving along very well and the orderly procedure of it should not be disturbed too often by special appearances." 15

Under this system, press comment on the WAAC varied. Many newspapers faithfully and favorably reported all that was furnished them, although this was not plentiful enough to build public knowl-

[194]

edge and acceptance to a degree that would insulate the WAAC against the later rumors. Certain anti-Administration newspapers from the beginning made the WAAC the subject of caustic comment, evidently regarding the Corps as a New Deal creation. Even in the most favorable press, there was a natural tendency for "news" to consist of those items amusing or spectacular enough to reach reporters directly, such as stories headlined, STORK PAYS VISIT TO WAAC NINE DAYS AFTER ENLISTMENT,16 or, ARE WOMEN PERSONS? DEBATED BY HOUSE VETERANS COMMITTEE.17 There was also a tendency for headlines to include the word WAAC in reporting all accidents, murders, suicides, and family troubles involving a member of the Corps; a headline that might more properly have read ARMY OFFICER TRIED FOR BIGAMY became, instead, WAC BRIDAL BRINGS TRIAL.18 Even when friendly newspapers arranged for visits of their own reporters and photographers or foreign correspondents, the results frequently tended toward the coy or frivolous rather than a serious emphasis on actual WAAC jobs.19

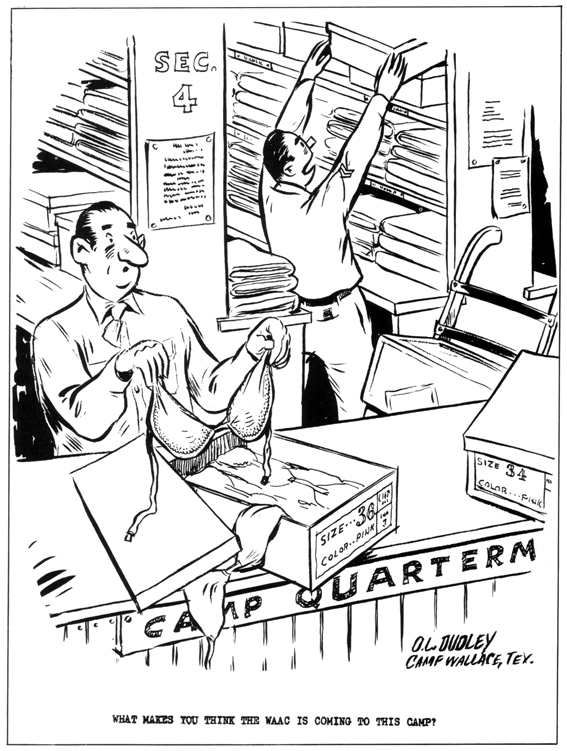

Also, from the first, cartoonists had found the WAAC amusing and had contributed caricatures which ranged from light humor to emphasis on anatomical detail. Of these, a training center commandant protested to WAAC Headquarters: "There seems to be no restraint on funny papers and cartoons with the WAAC as subject matter." He was informed that "legally there is nothing that can be done to restrain cartoonists from caricaturing the WAAC." 20

The more extreme actually were seldom commercial cartoons, but were more often soldier products from camp newspapers, which held with rather monotonous lack of originality to the idea that the best way of ridiculing a woman was to exaggerate those portions of her figure that differed from the masculine version. Although peculiarly masculine garments were not considered funny, the mere depiction of a brassiere, empty or otherwise, was alone enough to seem comic to cartoonists.21

Certain clergymen had also published their protest against the Corps as an improper place for young Christian women. Of these, the Catholic chaplain at Fort Des Moines wrote:

It is unfortunate that the few clergymen who have sounded off against the Corps get so much publicity, while the thousands I know who are in favor of it get little or no publicity . . . . I have had to have three masses every Sunday-about 1,400 Waacs each Sunday.22

Attacks by Private Letter and Gossip

These relatively minor cases of poor published and broadcast publicity or ill chosen humor bore little resemblance in degree of virulence to the slander campaign which followed, and which had an entirely different character. The first manifestations of a deeper change in public opinion came early in 1943, when there began to be evidences of more vicious attacks on the Corps spread by word-of mouth gossip and by private letter. Some of these were merely the "nut" letters that any organization might expect; quite often these included miscellaneous charges of

[195]

[196]

vice in the armed forces, or attacks on "the people in the White House" for permitting card playing and drinking by soldiers.23

Some letters were more dangerous than their character warranted. A typical example was a letter from an Army nurse to an Arkansas radio evangelist, which began, "I am a Christian and a member of the . . . Church and hate sin as bad as anyone." She then alleged that Waacs at training centers were lined up naked for men medical officers to inspect, that no sheets were used on examining tables, and that medical officers showed Waacs pictures of naked men and of men sitting on toilets. She concluded, "Christ loves these girls and I know he does not like for them to have to line up naked and it is embarrassing for our girls every month. Please send me your book The Truth About the Mark of the Beast, also Satan's Children."

The radio evangelist naturally became indignant and wrote his senator, saying that he intended to warn Arkansas parents and, "I am not going to permit Arkansas to become a Socialist State under the New Deal." He also sent copies of the letter to the governor, the Secretary of War, and three editors. 24 Upon the senator's request, an Army inspector general flew to Arkansas, launched a full-scale investigation, and discovered that none of the allegations was true and that the nurse in question was currently hospitalized with a diagnosis of mild psychoneurosis; she had also written similar letters about the Army Nurse Corps.

This, of course, was merely one of hundreds of such letters; the WAAC seemed to be a favorite target of mentally unbalanced persons. Unfortunately, although disproof for such allegations was readily available, it did not always reach all who had heard the charges.

Other scattered reports indicated that the WAAC was also encountering gossip and animosity from more responsible elements of the population. This was particularly true around all training centers, where numbers of Waacs were so great as seriously to inconvenience civilian users of streetcars, shops, and beauty parlors. An Army Service Forces inspector noted that, while Des Moines merchants and civic leaders had offered much co-operation, certain citizens were displeased, and added:

It seems that any dislike of WAAC personnel is not caused by disorderly or promiscuous conduct, but rather by the fact that the WAAC personnel, in the strength superimposed upon a city the size of Des Moines, makes it appear that they take over the town at such times as they are free, particularly Saturday and Sunday, which causes some amount of inconvenience. . 25

Investigation at Des Moines by the Army's Military Intelligence Service was unable to discover any basis for such dislike except "resentment on the part of local citizens . . . to the presence of strangers who they feel are usurping the old settlers in restaurants, stores, theaters, and hotels."26 The Director of Intelligence, Seventh Service Command, after investigating Fort Des Moines, said "It was conclusively determined during the course of the investigation that the morals of the members of the Corps are exceptionally and surprisingly good." 27 He

[197]

pointed out, however, that one example of WAAC misconduct in a bar would create much more gossip than identical conduct by scores of local civilian women.

As WAAC companies spread to the field, similar local animosity was sometimes noted near these units. For example, USO facilities and Stage Door Canteens at times discouraged or prohibited attendance by Waacs, defending this action by saying that Waacs broke rules by going outdoors with men between dances; which hostesses could not do. Waacs felt that they were not welcomed simply because USO hostesses were not interested in raising the morale of military personnel except of the marriageable variety.28

Another variety of gossip began to plague the WAAC perhaps more than any other in the spring of 1943. It arose from the fact that the public began to attribute to the WAAC certain misconduct which, upon investigation, proved to be that of civilian women in near-military uniforms. For example, an Army recruiting officer in Louisiana reported that Waacs, probably on leave from the Fifth Training Center, were drinking heavily in Shreveport bars and taking men to their hotel rooms. Investigation by the provost marshal revealed that the women in question were indeed conducting themselves as stated; they were not Waacs but "a group of women ordnance workers wearing a uniform identical with that of the WAAC except for insignia.'' 29 The Women Ordnance Workers, better known as WOWS, were civilian employees of Army Ordnance; although the majority of such employees did not wear uniforms or misconduct themselves publicly, a certain number caused rumors in all parts of the country. For instance, Ninth Service Command and AAF authorities in California both protested to the Director that some of the Wows were drinking to excess and engaging in barroom brawls, and being mistaken for Waacs. Investigation disclosed that the Wows at Stockton Ordnance Depot were wearing khaki shirts and skirts, garrison caps, and enlisted men's or officers' insignia.

The ordnance depot, after the investigation, ordered removal of Army insignia, but allowed retention of the uniform, which was optional with such workers all over the nation. Their winter uniform was of olive-drab elastique, like a WAAC officer's except for patch pockets and garrison caps; they also wore depot sleeve patches and miniature shields and ordnance insignia. Being civilian workers, they were under no restrictions as to conduct, hours, or neatness.

The same ordnance depot, like hundreds of other Army installations, also employed civilian women drivers who were allowed to wear khaki shirts, slacks, and garrison caps, with sleeve patch and shield insignia. The same region in California also had a civilian volunteer group, the Women's Ambulance and Defense Corps of America, which had a khaki uniform with Army insignia of rank and the letters WADC on a sleeve patch; these women, however, were forbidden by their bylaws to drink in uniform.

[198]

The Ninth Service Command investigators, after study of uniforms of the WOWS, women drivers, and WADC, concluded that the public was undoubtedly taking all of them for Waacs, unless they investigated insignia and button design closely.30

This was only the beginning of what seemed to be an attempt by every woman in America to get herself into a military uniform without the inconvenience of subjecting herself to WAAC discipline. Civilian clerical workers in many Army offices bought officers' "pink" skirts and olive-drab jackets with gold buttons. The Civil Air Patrol women were authorized by the AAF, without clearance from WAAC Headquarters, to wear WAAC uniforms with red braid and silver buttons. Even the WAAC "Hobby Hat" was not sacred; secretaries at Valley Forge Military Academy wore a close copy, with a uniform almost indistinguishable from a WAAC officer's. When WAAC authorities protested this to the academy, they were informed by the professor of military science and tactics that the uniform was not at all similar since the skirt had a pleat and the buttons had the academy crest and not the WAAC eagle. At Fort Devens a soldier's wife was found wearing a WAAC uniform with gold U.S. Army buttons and her husband's insignia; she said the uniform was one that "they sold in Philadelphia" to girls whose husbands were in the service.31

Eastern stores advertised a "junior WAAC uniform" in sizes up through 14 guaranteed to be "an exact copy of the real WAAC uniform." The Quartermaster General informed the Director that its sale was not illegal, although its wearing by an adult might be, depending on circumstances.32 A New York manufacturer supplied dress shops all over the country with a uniform quite similar to the Waacs', advising them:

STAKE YOUR CLAIM. There is a vast new field open for you in selling to the army of Women Volunteer Workers-Air Raid Wardens-Minute Men-Canteen Workers-USO and scores of others. ALL DOING THEIR PART AND ALL WANTING TO DRESS THE PART.33

It was doubly annoying to WAAC Headquarters that these concerns were able to get olive-drab and khaki cloth in the early months when The Quartermaster General was still unable to get it for WAAC uniforms.

These department store uniforms were bought and worn not only by volunteer workers but by scores of organized prostitutes in Eastern cities. Staff Director less Rice of the Third Service Command, working with the provost marshal, gathered and forwarded to WAAC Headquarters irrefutable evidence of this practice. The streetwalkers, known as Victory Girls, were discovered in Harrisburg, Newport News, Baltimore, and other cities, wearing uniforms of material and cut very similar to the WAAC's. One was apprehended by military police while trying to buy a furlough-rate railroad ticket. Another was discovered when authorities checked a report that a WAAC officer was drunk in a disreputable Harrisburg hotel. The proprietress of a Baltimore clothing

[199]

store claimed that she was doing a good business in sale of these uniforms and "desired to know if she was doing wrong in selling them.34 At the Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation, the camp followers, dressed in khaki skirts and shirts, were so bold as to wait outside the gate, claiming that they were Waacs and picking up soldiers as they left the port. Here, the commanding general ordered the enrolled women to pin their insignia on the collars of their cotton shirts, at that time contrary to uniform regulations, so that they could be distinguished from prostitutes in khaki shirts and skirts.35

Gathering together all these examples, Director Hobby requested the Army Service Forces to amend Army regulations so as to forbid the civilian use of WAAC uniforms and insignia, or that of any insignia, buttons, and clothing which very closely resembled the WAAC items. She also asked that the Quartermaster Corps and Army Exchange Service co-operate in discouraging manufacturers of these uniforms. Since the Army controlled the manufacture and sale of all material used in commercial manufacture of Army officers' uniforms, it could, by withholding material, force most manufacturers to cease wasting it in the production of nonmilitary uniforms.

However, the Army Service Forces rejected the Director's idea, saying that it would be too difficult to enforce and that the Quartermaster Corps and the Exchange Service already co-operated with manufacturers of male officers' uniforms, so that no new instructions to them were necessary. The ASF added "Due to the fact that the WAAC is a comparatively new corps, the casual and uninformed observer is apt to believe that every woman in o. d. uniform is a Waac. It is believed that this situation will be overcome in due course." 36

The Quartermaster General soon afterward authorized the lend-leasing of 5,000 WAAC winter uniforms, left surplus by the collapse of recruiting, to the French "WAAC" in North Africa-at that time a part-native corps without military organization. The Director shortly received a flood of derogatory letters from soldiers, in parts of North Africa where there were no Waacs, who nevertheless alleged that Waacs were disreputable in both appearance and conduct, wore earrings and bobby sox with uniforms, also long hair down their backs, and obeyed no military commands.37

By late spring, even before the Cleveland Plan was launched, rumors were more widespread, more consistent, more vicious, and the tempo of their occurrence had quickened. Director Hobby and War Department officials now began to suspect that Axis agents had taken over the sporadic stories and were systematically spreading certain definite rumors in an attempt to discredit and wreck the WAAC and thus impede the Army's mobilization. This theory was supported 'by the fact that the onset of the more vicious rumors followed immediately after the Congressional hearings in March of 1943, in which Army

[200]

leaders had asked Army status for the WAAC and had emphasized that thousands more women were sought to allow more men to be sent to strengthen the fighting front. The Waacs already obtained, it was said; would release for combat a number of men equal to that which had just defeated the Germans in North Africa.

As early as 18 May 1943, Director Hobby wrote to General Grunert that "there have been many indications of an organized whispering campaign directed against the WAAC" and asked investigation. The Army Service Forces sent the request for an investigation to G-2 Division, General Staff. which in turn sent it to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, claiming that it was out of the Army's jurisdiction.38

By early June, the situation was so far out of control that G-2 Division reversed its stand and requested the FBI to allow it to act. In a letter to the FBI, G-2 Division said:

Consequent to the formation of such a women's auxiliary to any of the military services, a certain amount of indecent humor was to be expected. However, the inevitable so-called humor first has been supplemented and subsequently has been replaced by a circulation of plainly vicious rumors . . . what appears to be a concerted campaign has assumed such proportions as seriously to affect morale and recruiting.39

Supporting evidence for this view was plentiful. An identical rumor appeared almost simultaneously in New York, Washington, Kansas City, Minneapolis, and other cities, to the effect that large numbers of pregnant Waacs were being returned from overseas. Camp Lee, Virginia, was swept suddenly by the report that any soldier seen dating a Waac would be seized by Army authorities and given medical treatment. A widely repeated rumor circulated at Hampton Roads to the effect that 90 percent of Waacs had been found to be prostitutes, 40 percent of them pregnant. In the Sixth Service Command an apparently organized rumor appeared in many localities to the effect that Army physicians examining WAAC applicants rejected all virgins. In Philadelphia a "War Department Circular" with obscene anatomical "specifications" was reproduced and widely circulated, finally being found even in the foxholes of New Guinea. From Florida there came numerous identical stories that Waacs openly solicited men and engaged in sex acts in public places.40

One favorite theme for these organized rumors was that Waacs were issued prophylactics or were required to take such items with them when they left the barracks, so that they could fulfill the "morale purposes" for which the Army had really recruited them. It was this story that finally brought the whole slander campaign into the open. Until this time, Army and WAAC authorities had felt it wiser to ignore all rumors, since to deny any publicly would merely have given them greater circulation. However, on 8 June 1943, the charge that Waacs were issued prophylactics was made in a nationally syndicated column, "Capitol Stuff," in the McCormick chain of newspapers, by a columnist

[201]

THE PRESIDENT AND MRS. FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT visit the Waacs in the spring of 1943. Above, Mr. Roosevelt reviews the troops al Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia. Below, Mrs. Roosevelt with Director Hobby and Col. John A. Hoag, commandant of First WAAC Training Center at Fort Des Moines.

[202]

who had continuously opposed Administration measures. It was noted that in the weeks preceding the appearance of the column Mrs. Roosevelt had visited the Waacs at Des Moines and the President himself had reviewed those at Fort Oglethorpe, after which he had informed the press that "those of us who have seen the work they are doing . . . have only admiration and respect for the spirit, the dignity, and the courage they have shown."41

On 8 June the column stated:

Contraceptives and prophylactic equipment will be furnished to members of the

WAAC, according to a super-secret agreement reached by high-ranking officers of

the War Department and the WAAC Chieftain, Mrs. William Pettus Hobby . . . . It

was a victory for the New Deal ladies . . . . Mrs. Roosevelt wants all the young

ladies to have the same overseas rights as their brothers and fathers.42

There was actually no truth in the statement. The Army did provide free prophylactic equipment for men, and it appeared theoretically possible that some station in the field might have attempted to apply the same rule to women. However, the most thorough investigation by Army operatives from G-2 Division failed to produce any such evidence. These operatives reported:

There is apparently no factual basis for the . . charge that contraceptives and prophylactics are issued to WAAC personnel. It is indicated that these articles are not even generally purchased in Post Exchanges and drug stores by individuals in the WAAC; in all cases of recorded sales the purchasers have been married women.43

It was G-2's opinion that the "super-secret" document referred to was a War Department printed pamphlet for the WAAC, Sex Hygiene, which prescribed six lectures to be given WAAC officers and officer candidates, to equip them to give their women a suitably modest version of the Army's required hygiene course for men.44 This was, however, an unsensational document, part of the routine training course, which prescribed standard subjects no more radical than those given in high schools and colleges-feminine anatomy and physiology, the nature and dangers of venereal disease, and the facts about menstruation and menopause-and which said nothing whatever about the issue of contraceptives. Its wording had in fact been carefully reviewed by the Director, and its presentation limited to trained WAAC officers, because of the British experience:

Exaggerated rumors appear to have gathered about hygiene lectures in the forces .... The mental reaction of a girl unaccustomed to attributing precise meanings to words, and bewildered by the impact of new and unfamiliar terms, must be kept in mind.45

G-2 described the pamphlet as "'an excellent, frank, and wholesome manual . . . [which] counsels continence."46 It definitely did not authorize any issue of contraceptives, and did not even tell the women what they were or how to use

[203]

them. This, just published on 27 May 1943, could have been the "agreement" mentioned in the 8 June column, although it was not "'super-secret" or even secret or confidential but merely restricted to military personnel. Save for this, G-2 found that no directives on the subject had ever been issued by WAAC Headquarters except one letter in May, in answer to an inquiry, which said definitely that Waacs would not be given even so much as instruction in the use of prophylactics, much less the prophylactics themselves.47

The War Department thus was in an excellent position to force the columnist to retract his statement. The question was whether it would be wise to lend the affair the dignity of a formal War Department denial. Many of the Director's advisers counseled against it, pointing out that persons would read the denial who had never read the attack, and that the present distress, anger, and humiliation experienced by the Director and all other Waacs would in time be forgotten. On the other hand, the shock which the column had caused the Waacs and their families was so great that an immediate denial seemed necessary to preserve the faith and self-respect of the Corps. An Army officer described a typical reaction in the WAAC company on his post:

It raised hell with that company. Long distance calls from parents began to come in, telling the girls to come home. The younger girls all came in crying, asking if this disgrace was what they had been asked to join the Army for. The older ones were just bitter that such lies could be printed. It took all the pride and enthusiasm for the Army right out of them. 48

An enlisted woman described the same reaction; she said:

I went home on leave to tell my family it wasn't true. When I went through the

streets, I held up my head because I imagined everybody was talking about me,

but when I was at last safe inside our front door, I couldn't say a word to

them, I was so humiliated-I just burst out crying, and my people ran and put

their arms around me and cried with me. I couldn't understand how my eagerness

to serve our country could have brought such shame on us all.49

Director Hobby herself, when she gathered her staff to tell them what had happened, broke down and was unable to continue speaking. The severity of the reaction of all Waacs, in whatever ranks, could be explained only by the fact that all, at this date, were the early pioneers whose enlistment had been motivated by a perhaps impractical idealism, intense enough to sustain them through the supply and training problems of the first winter, but too intense to receive such a gross attack with the indifference its inaccuracy merited.

Director Hobby therefore made the decision to reassure the women and their parents by public denials, whatever the effect on newspaper readers. Such denials were thereupon immediately made by the President and Mrs. Roosevelt, by Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, by General Somervell of the Army Service Forces, by members of Congress, and by Director Hobby and other WAAC officers. The President told his press conference that it was a "deliberate newspaper job" and that the reporter had merely taken orders

[204]

"from the top."50 Mrs. Roosevelt in her press conference on 8 June stated that rumors about misconduct among Waacs in North Africa were Nazi propaganda, and that "Americans fall for Axis-inspired propaganda like children."51 Naturally, she said, the Germans were interested in discrediting an organization that released so many men for the fighting front.52

Secretary Stimson's denial was the most publicized, and did in fact reach many people, especially on the west coast, who had never heard of the columnist or the rumors:

Sinister rumors aimed at destroying the reputation of the Waacs are absolutely and completely false. Anything which would interfere with their recruiting or destroy the reputation of the Corps, and by so doing interfere with increase in the combat strength of our Army; would be of value to the enemy. The repetition of any unfounded rumor . . . is actually an aid to the enemy.

He pointed out that reflection on the WAAC was reflection on the whole of American womanhood, and that to malign the nation's women could easily destroy the morale of men at the front." 53

In addition, General Somervell told a Congressional committee that the rumors were spread by a person sympathetic to the Axis and that the Waacs were "your and my daughters and sisters" and entitled to respect.54 Representative Edith Rogers told Congress that "nothing would please Hitler more" than to discredit Waacs and American women. Representative Mary Norton said, "Loose talk concerning our women in the Armed Services cannot be less than Nazi-inspired.55 Director Hobby told reporters that there was "absolutely no foundation of truth in the statement."

Under the barrage, the columnist was forced to retract his statement, which he did, although protesting that his information came from an "intelligent and trustworthy" official who swore that "his eyes had passed over" the alleged secret paper.56 Nevertheless, three years later, religious publications were still to be found reprinting the story, and actually attributing the columnist's lines to Director Hobby. Director Hobby's picture was labeled "Astounding Degeneracy," and one article continued, "Mrs. William Pettus Hobby, chieftain of the WAC, says, 'Contraceptives and prophylactics will be furnished to members of the WAC according to a super-secret agreement reached by high-ranking officers of the War Department.57

Investigation by Intelligence Service

In June, a full-scale investigation of possible Axis influence in the rumors was launched by the Army's Military Intelli-

[205]

gence Service. The Federal Bureau of Investigation gave the Army full permission, in this one instance, to investigate persons who might otherwise fall under the investigative jurisdiction of the FBI.58

A more exhaustive investigation could scarcely have been made than that which Military Intelligence now undertook. First, Army agents covered sections of the nation near large WAAC installations, such as training centers. At Des Moines, for example, more than 250 interviews were held with a cross section of the local citizens, in an effort to expose the source of the rumors. Next, specific stories all over the nation were tracked down to their beginnings, each involving a large file of notes and records.59

The report reached a conclusion far less pleasant than the theory of Nazi

activity:

There is no positive evidence that rumors concerning the morality of WAAC

personnel are Axis-inspired. There is some evidence that the Axis-controlled

radio has followed a line of rumors already widely circulated by . . . Army

personnel, Navy personnel, Coast Guard personnel, business men, women, factory

workers and others. Most . . . have completely American backgrounds.60

Evidence indicated that in most cases the obscene stories had been originated by men of the armed forces at about the time of the change from the "phony war" to real combat in North Africa, and of Congressional publicity on the thousands oh women sought to release men for combat. From Army and Navy men, the stories had spread rapidly, first to their wives and women friends, and thence to the whole population. Eventually the rumor spreaders included, according to G-2 secret files:

(1) Army personnel. "Army officers and men who resent members of the WAAC . . . who have obtained equal or higher rank than themselves." "Men who fear they will be replaced by Waacs." "Male military personnel who are sometimes inclined to resent usurpation of their long-established monopoly." "Soldiers who had never dated Waacs . . . [or] had trouble getting dates."

(2) Soldiers' Wives: "Officers' wives over bridge tables." "Women whose husbands are shipped overseas.''

(3) Jealous Civilian Women: "Local girls and women who resent having the Waacs around." "Younger to middle-aged women who deplore the extra competition." "Women who ordinarily participate in community enterprise and who are losing publicity as a result of women in uniform."

(4) Gossips: "Thoughtless gossiping men and women." "Men [who] like to tell off-color stories."

(5) Fanatics: "Those who cannot get used to women being any place except the home." "Those whose rabid political convictions cause them erroneously to see in the WAAC another New Deal creation."

(6) Waacs: "Disgruntled and discharged Waacs." 61

A typical example of an unfounded rumor that spread in the standard pattern was the case involving a Midwestern city and the surrounding area. In this city, agents reported, enlisted men and officers in bars had begun the rumors with statements of which the more printable included, "Waacs are a bunch of tramps"; "All Waacs have round heels"; and "Waacs are nothing but prostitutes." In small towns nearby, officers' wives soon

[206]

afterward stated to friends that Waacs were really taken into the service to take care of the sex problems of soldiers. An Army chaplain then advised Waacs not to re-enlist in the WAC. The rumors spread to Protestant and Catholic ministers in the vicinity, who then urged Waacs to get out of the service. These were investigated by the FBI for sedition in urging desertion.

Agents were not able to verify even one case of pregnancy of an unmarried Waac in that area, or any other notorious misconduct.62

In New England, especially in the Fort Devens area, agents found that a number of stories about mass pregnancy, venereal disease, and immorality had originated with military personnel. The G-2 report added:

Military personnel, commissioned and enlisted, were found to be a prolific fountainhead of WAAC rumors. Soldiers who had never dated Waacs, and consequently didn't know whether the stories were true, accepted the tales as gospel. Army nurses are allegedly jealous of the Waacs because the latter are promoted more rapidly, receive more publicity, and encroach on the nurses'' dating territory. The wives of men replaced by Waacs are said to be angry because their husbands are sent overseas as a result of the Waacs supplanting them. No subversive intent is apparent in either case.

Soldiers in the Fort Devens area were credited by investigators with originating the rumor that "fantastic" numbers of pregnant Waacs had been sent back to Lovell General Hospital from North Africa. Agents descended on that hospital's records "without prearrangement" and reported, "No record of a pregnant Waac was found." In fact, no Waacs pregnant or otherwise had ever been returned from North Africa to Lovell General Hospital. Another Fort Devens' rumor among military personnel was that the WAAC venereal disease rate was skyrocketing. When 6,000 women were examined, only 11 cases were discovered, 8 of them having existed before enlistment and having been undetected by entrance examinations. This, agents said, was a rate which was "less than any civilian community.'" A third rumor in New England was that Waacs were officially advised to utilize contraceptives. Agents interviewed hundreds of Waacs and were unable to find even one who had ever been so advised; the Catholic chaplain also asserted that no Waacs in the area had ever to his knowledge been given such advice. 63

In the Fort Des Moines area, where Waacs had been longest, rumors were not so vicious; the attitude of male military personnel, originally quite hostile, had reportedly upon closer acquaintance taken a marked change for the better. The Director of Intelligence, Seventh Service Command, concluded, "It is obvious that the Corps members, by force of their own composite opinion, do much to enforce proper conduct and freedom from even the appearance of evil on the part of other members.64

Agents at Fort Des Moines reported that no soldier could be found who had ever had sexual intercourse with a Waac; in fact, most had trouble getting a date. Sales of contraceptives at local drug stores had not gone up. Waacs drank less in public than civilian women, and it was found that "merchants agree Waacs are more courteous and patient, meet obligations more readily." All interviewed who knew Waacs placed the sexual morality of the

[207]

average member as higher than that of the average civilian girl. Nevertheless, a relatively few instances of drunkenness and misconduct had made a proportionately greater impression on local citizens. Since Waacs originally did not have to wear uniforms off duty, local citizens also showed a tendency to consider any drunken woman a disguised Waac, until training center authorities forbade wearing of civilian dress in the Des Moines area.65

Near the Fifth gaining Center, a Capt. Charles S. wrote a Waac friend that he had heard there were 165 "pregnated" Waacs in one month at Camp Polk, and that before members went out on passes they were required to show that they had contraceptives with them. When asked for proof by Military Intelligence, Captain S. was, agents said, "much chagrined and embarrassed."66

In the area around Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia, agents reported evidence that rumors had been spread by men who resented WAAC rank or who thought they would be shipped overseas as soon as enough Waacs could be recruited to replace them. Local girls and women had picked up the rumors; one admitted to agents that she had spread stories which were not true but that. "I just get tired of seeing them around." A rumor about 100 pregnancies was traced to the local WCTU. Again, statistics failed to support the charges. Of 14,000 women trained or processed since the training center opened, three had been hospitalized for drunkenness, and eight had venereal disease, which agents described as a "negligible" percentage of cases compared to civilian rates. Hotel owners and the director of the Chamber of Commerce said Waacs conducted themselves better than civilian girls.67

Investigation at Daytona Beach

The most extensive training center investigation was conducted at Daytona Beach, where the Second WAAC Training Center and General Faith's headquarters had operated in the midst of a resort city. In January Director Hobby had renewed her attempts to get the women out of the city area, and in March the Services of Supply approved construction of classrooms and one theater but again refused to approve construction of recreational buildings.68

As a result, large numbers of recreation seeking Waacs descended on the city nightly, provoking much civilian resentment and some of the most serious allegations encountered by investigators. At first these objections concerned only the crowding and food consumption by Waacs: one winter resident, who described himself as "a lover of the locality and its facilities as an adorable resort," wrote his senator to denounce WAAC service as "a grand vacation at Government expense . . . the Army group monopolizes our few sizeable restaurants to the detriment of civilians." Investigators found that most such complaints came from about 15 percent of the local residents described as "well-to-do property owners . . . the

[208]

elderly conservative type."69 Another civilian criticism alleged that WAAC messes wasted food so that their garbage cans were filled to overflowing while Florida civilians went hungry under the administration's food rationing system. Instead, investigators found that the disposable garbage rate in WAAC messes was only half that of the Army rate; the local garbage collector, when interviewed, stated that what he found in WAAC garbage cans was far less than that from "civilian sources."70

Rumors nevertheless grew more vicious. It was said that WAAC trainees drank too much; that they picked up men in streets and bars; that they were registered with men in every hotel and auto court, or had sexual relations under trees and bushes in public parks; that there was a nearby military hospital filled to overflowing with maternity and venereal disease cases. Finally, it was seriously stated that Waacs were touring in groups seizing and raping sailors and Coast Guardsmen.71

To evidence to support such statements could be found by military intelligence operatives, or by independent investigations by the Fourth Service Command, or by Colonel Clark of WAAC Headquarters.72 The alleged government maternity home was nonexistent; only 18 pregnancies had been discovered. 16 of them among married women; inspectors could get locally only hearsay and gossip but "no single piece of correspondence which would indicate any tangible item."73 Although the center had almost 10,000 trainees, the military police report for a typical Saturday night revealed a total of only 11 delinquencies:

2 kissing and embracing in public

1 no hat on

2 injured in auto accident

1 without identification card

1 walking with officer on street

2 found intoxicated

1 AWOL returned

1 "retrieved from Halifax River in an intoxicated condition"

11 Total

This was accounted a remarkable record in view of the fact that, among the thousands of women at the Second Training Center in this first week of May. 1943, many were the mental, moral, physical, and psychological problems that had been accepted in such large numbers before the restoration of recruiting standards. However, it was admitted that rumors would naturally spread through the local civilians if even one Waac out of 10.000 had to, be retrieved from the Halifax River every Saturday night.74

The inspectors and the local authorities

[209]

unanimously blamed the location and the lack of recreational facilities. The area was described as the week-end mecca of soldiers and sailors from surrounding military and naval stations. An Army investigator observed, "From Saturday noon until midnight Sunday, Daytona Beach takes on an atmosphere of a large coeducational institution at which the home team has just won an important football game."75 One officer reported. "It was a crazy idea to try to set up a Military Training Center in a place: like this where the girls live in hotels and are surrounded by a carnival atmosphere." 76

The Fourth Service Command inspector general recommended more recreation facilities so that trainees would not need to roam the city at night. The military intelligence operative agreed: "It is the opinion of this officer that recreational facilities are inadequate." 77 Ninety percent of the women had, he said, stayed in their quarters and suffered low morale, while only about 10 percent were seen in the city, but this 10 percent totaled a thousand women. General Grunert, who investigated in person, immediately telegraphed his office:

RECREATION FACILITIES AVAILABLE TO WAAC TRAINING CENTER HERE AT DAYTONA BEACH ARE SO GROSSLY INADEQUATE AS TO MAKE IT NECESSARY TO RECONSIDER THE QUESTION OF PROVIDING TWO SERVICE CLUBS . . . . PRESENT USE OF INADEQUATE CIVILIAN FACILITIES HAS RESULTED AND WILL CONTINUE TO RESULT IN COMPLAINTS AND RUMORS AS TO DRINKING AND IMMORALITY AND DEPLETION OF CIVILIAN FOOD SUPPLY . . . . TAKE UP THIS MATTER WITH COMMANDING GENERAL ARMY SERVICE FORCES AT ONCE FOR EARLY ACTION. 78

Now, belatedly, Requirements Division, ASF, reversed its earlier disapprovals and approved Director Hobby's four-month old recommendation for two service clubs, but the time required to bring them into operation was considerable, and in any event the damage was irretrievable.79

In addition, inspectors blamed some rumors at Daytona Beach on the conduct of female dischargees who remained about town "'conducting a campaign against the WAAC.80 General Faith noted that, in the weeks before recruiting standards were restored, about one half of 'l percent of the women sent him had previous records which warranted their immediate discharge, and that in addition another 4 percent were guilty of "unseemly conduct . . . specifically, drinking, boisterousness, and petting in public parks and on benches.'" The remaining 95 percent he believed to be of exemplary conduct and discipline, a good statistical average for any civilian community. General Faith stated, "I am convinced that faulty recruiting is the primary cause of the conditions described." 81

No matter how promptly such women were discharged, civilian gossip had opportunity to multiply their numbers and to confuse the conduct of dischargees with that of trainees. WAAC military police attempted to take uniforms from dischargees who were wearing them for a purpose other than the official one of return to the place of enlistment, but in one such case a woman discharged for neurosis promptly ran screaming into the street disrobed, causing even worse public comment.

[210]

Colonel Clark, who investigated for WAAC Headquarters, said:

Being considerably alarmed by rumors . . . I took the trouble to ascertain from

the hospital records the true facts with regard to pregnancies and venereal

diseases. These figures are statistical and incontrovertible . . . . It will be

seen at a glance that the experience of this center in this respect has been

unusually fortunate . . . . It is extremely unfortunate that we have no recourse

against these scurrilous and slanderous charges.82

The Army did have one recourse, and that was to abandon all city property-a

move also dictated by the shrinking enrollment. At this, a local newspaper

columnist cried:

It may be that the present scare that the War Department would forego Daytona

Beach . . . will close the traps of some of the scandal mongers . . . . Had it

not been for the coming of the Waacs, Daytona Beach would by now have been a

ghost town.83

In July, the Waacs gave up the leased city buildings and withdrew within the cantonment area, and the local radio station broadcast, "Cool Daytona Beach can once again accommodate thousands of summer visitors." 84

It was from overseas, where most soldiers had not as yet seen a Waac, that the worst opposition came. The Office of Censorship ran a sample tabulation and reported that, of intercepts of soldier mail which mentioned the WAAC, 84 percent expressed disfavor and most advised a woman not to join; some threatened to jilt or divorce her, as the case might be, if she did join.85

The only Waacs then overseas were some 200 in North Africa and about 600 bound for England, but, according to the soldiers' reports, each must have been shipped home pregnant several times. A counterintelligence operative, sitting in a restaurant next to an Army major, heard him say loudly that the Army had sent "a whole boat-load" home and that it was "difficult to keep Waacs at any station over there for any length of time without fully two-thirds of them becoming pregnant." 86 A civilian just returned from North Africa cautioned his women friends against joining the WAAC because of the low moral character of nurses and Waacs, but when pressed for facts was unable to furnish the names of any specific persons or places, and admitted he had no direct knowledge of the matters 87

One favorite rumor was that General Eisenhower had said that he didn't want Waacs "'dumped on his command area." Foreign correspondents interviewed General Eisenhower and found that he had not only requested Waacs but said he would get British servicewomen if American ones were not sent. One reporter discovered that Waacs in North Africa lived in a convent under strict discipline, rose early to catch a 6:00 A.M. military bus to town, worked hard all day; securing enthusiastic recommendations from supervisors, and retired to the convent for an 8:00 P.M. curfew. He therefore failed to see how their night life could be very exciting. 88

[211]

Among all the comments reported in later samplings by the censors, who of course had no power to delete them, there were many praising the Corps and its work, but not one reported instance in which a man advised a woman to enlists.89 Typical soldier comments, from many units and from widely separated parts of the world, were:

Wife of one of the men in my company joined the Wacs. She simply wrote and told him that, tired of living off the fat of the land, she had enlisted. With no further ado, the man wrote his father's attorney to institute divorce action . . . and is at present engaged in cutting off her allotments, changing insurance beneficiaries . . . .

You join the WAVES or WAC and you are automatically a prostitute in my opinion.

I think they are great organizations, but I don't want any wife, or future wife, of mine joining them.

Are you going in the Wacs, Mother? If you did or do, I will disown you.

Velva, please don't join the Wacs. I have good reasons for not wanting you to. I persuaded my sister not to. Some day I'll tell you why.

You ask me to tell you what I think of the Wacs and Waves with the idea of you joining in mind. Darling, that sort of puts me on the spot. If the idea of you joining were not involved, I would say that they have proven a proud, worthwhile part of our armed forces.. But from the standpoint of you joining is something else again . . . very emphatically I do not want you to join.

I think it is best that he and Edith are separating, because after she gets out of the service she won't be worth a dime . . . . I would not have a girl or wife if she was in the service even if she was made of gold.

Any service woman-Wac, Wave, Spar, Nurse, Red Cross-isn't respected.

I told my Sis if she ever joined I would put her out of the house and I really meant it. So if you ever join I will be finished with you too and I mean it.

I think it is enough to say that I am not raising my daughters up to be Wacs.

It's no damn good, Sis, and I for one would be very unhappy if you joined them . . . . Why can't these Gals just stay home and be their own sweet little self, instead of being patriotic?

I just spoke to a couple of officers one of whose wife was so smart she joined and then told him. To give you an idea of what officers think . . . he told his wife to get a divorce. The other officer had to really tell off his daughter before she got such ideas out of her head.

Darling for my sake don't join them. I can't write my reasons because the censors won't let it through.

Honey don't ever worry your poor head about joining the Wacs for we went over all that once before, Ha! (Remember, over my dead body. Ha! Ha!) You are going to stay at home.

I would rather we never seen each other for 20 years than to have you join the Wacs. For gosh sakes stay a good girl (civilian) and I'm not just kidding either.

Ruth asked about the Wacs. The idea is noble but the widespread attitude of the public is narrow and bad. So I definitely don't recommend it.

I don't want you to have a thing to do with them. Because they are the biggest houres (I hope this gets through the censor.) Lousey, boy, they are lousey, and maybe you think my blood don't boil and bubble . . . . God, I'd disown anybody who would join.

The practice of women in the Army, still in my mind, is a glorified form of cheap bolshevism.

Lets not say no more about the auxiliaries for the idea makes me mad in the first place

[212]

and I don't want you galavanting around over the country for another thing. You will be better off chopping cotton . . . .

Your letter shocked me so and it was not appreciated by no means. If you join the Wacs, you and I are through for good, and I'll stop all allotments and everything.

I remember distinctly telling you before that your joining the WAC was one thing I would not tolerate. I told you distinctly that I didn't want to discuss it. Why do you persist' . . .

The service is no place for a woman. A woman's place is in the home.

About joining the Wacs the answer is still NO. If they really need service women let them draft some of the pigs that are running around loose in every town.

When you asked me the first time whether you could join the Wacs I refused and I meant that for all time. I want to come home to the girl I remember.

I cannot put this on paper how I feel and I am ashamed to tell my fellow officers. She cannot even consider herself as my wife from now on. I am stopping all allotments to her and am breaking off all contacts with her. Why she did such a thing to me I cannot understand. My heart is broken.

Get that damn divorce. I don't want no damn WAC for a wife.

In the last year of the war a censor summarized the situation:

Comments on the WAC continue to reflect much credit on their ability. Their

military bearing and adaptability to military life bring praise . . . [but]

there is no indication of a lessening of U.S. troops' opposition to friends and

relatives joining. WAC individuals indicate their disillusionment.90

In the spreading of rumors, the Waacs themselves were far from guiltless. Letters written home by disgruntled individuals frequently contained remarks about food, living conditions, and forced association with low and unsympathetic characters. For example, a young woman just arrived at a new station wrote her father:

Dear Pop:

Please don't show this letter to Mom. This place is like a concentration camp

and the C. O. and the First Sergeant have driven one girl to suicide and three

to going AWOL. The girl who went AWOL last night was a fine, clean girl, and

when she refused to submit to her Boss he threatened to court-martial her on a

trumped-up charge. A boy in Co. ". killed himself last night, I saw the note he

left with my own eyes. Two Chaplains have gone AWOL this week and can't be

found. Please don't worry. I'll stick it out as best I can, but it is leaving

its mark.

Somewhat naturally, her father sent this letter hastily to his congressman, who sent it to the Secretary of War, saying, "I have known her all of her life and have always found her to be honest, reliable, and trustworthy." A formal investigation was immediately held, at which it was discovered that none of the allegations was true: "Complainant stated that she addressed the letter to her father while in a mood of depression following her arrival at Camp D--. She acknowledged that the statements in her letter were based upon hear-say."91

The faulty recruiting techniques of the past months also resulted in receipt by civilians of long, incoherent letters from mentally disturbed individuals concerning persecution by officers, general misconduct among all officers and noncoms, or at least those who got promotions, and unwarranted punishments for the writer. Most alleged that they were sending copies to newspapers and friends. Investigation

[213]

of such cases ordinarily disclosed only that the writer "had great difficulty in adjusting to the military service,"92 or had just been discharged.

With the approach of the conversion to the Women's Army Corps, many women deemed undesirable members of the company were refused re-enlistment by their commanding officers; these included neurotics, behavior problems, and other troublemakers. Recruiters came to dread the return of one of these rejects to her community, knowing that she would probably spread ridicule and falsehoods about the Corps.93

The Question of Axis Influence

Army intelligence agents at this point began to concentrate upon tracking down individual stories with, originally, the hope that Axis agents would be found at the source. In only one case was there any such Axis connection: this was the rumor about the return of thousands of pregnant Waacs from North Africa. When this was painfully traced to its beginning, it was found to be based on an actual incident in which the first three Waacs were shipped home, two sick, one pregnant, the latter having been for some years the lawful wife of an Army officer who had spent a leave with her a few months before.

The Axis radio station DEBUNK then broadcast in English to North Africa the modest amplification that 20 Waacs had been returned for pregnancy. This broadcast, however, was less effective than that of a Coast Guard lieutenant who told friends at the Capitol in Washington that he was a member of an armed guard which was required on a ship bringing back 150 pregnant Waacs "to keep some of the women from jumping overboard." On a train from Washington to New York, a Navy commander gave the number as 300. By the time the figure was given in Minneapolis by a Navy enlisted man, it had reached 250,000. When questioned by the Office of Naval Intelligence, the Coast Guard lieutenant said, "It was spoken in jest." He was, the Navy said, then "admonished." The Navy commander had the misfortune to relate his story on the train to a man whose daughter was a Waac; this man took his name and wrote the Secretary of War. The Secretary of War asked the Secretary of the Navy for action. The commander then wrote the Waac's father, "The private conversation in which we engaged informally seems to have been seized on by you as the basis of some far-extending investigation, in which I do not intend to become involved." The War Department was not informed whether any action had been taken against the commander. 94

No other cases showed even a trace of Axis influence. A typical case was that of an insurance salesman in Philadelphia who wrote an Army officer that WAAC conduct was deplorable. When military agents appeared in his office and pressed for details, he alleged that Waacs had at various times accosted him and his friends, entered his hotel room, and showed him contraceptives in their purses. He refused to give names of the men friends who he

[214]

said were present when the alleged offenses occurred. His neighbors were asked for opinions as to his reliability and described him as "not reliable," "know-it-all," "a blowhard." He was not an Axis agent.95

Miss Helen A., a businesswoman in New York City, wrote Army authorities concerning the disgraceful situation at the --- Hospital ofJersey City, where, she alleged, there were 50 pregnant Waacs. When questioned by intelligence officers, she admitted that she had heard that story from a friend, Miss W Miss W. said she had the information from another friend who was having a baby at the hospital and heard two nurses in conversation outside her door. However, Miss W. finally admitted that the real source was a conversation she had overheard between two unidentified women sitting at the next table in a restaurant. The hospital submitted four affidavits to show that no Waac, pregnant or otherwise, had ever been there. Confronted with this evidence. Miss A. reportedly said that she "regretted writing the letter." None of the individuals concerned were Axis agents.96

In South Dakota, a civilian woman who had been assisting recruiters told them that she could no longer help recruit women unless they took steps to see that no more Waacs were sent overseas "to be tempted." She had heard that 5,000 had just been sent home from England for pregnancy. Recruiters told her that she must be wrong, since there were not that many Waacs in England, but she replied that she had the facts from her son, Capt. Harvey H., a medical officer in England. Recruiters reported this to the Director, who promptly wrote to the European theater requesting that they call to Captain H.'s attention "the implications of such statements on American woman-hood." Scarcely was Captain H. threatened with court-martial in England than his father telephoned from South Dakota to tell the Director that the whole thing had been a misunderstanding. None of the family were Axis agents.97

One of the lengthiest investigations concerned a suspected Nazi in New Jersey, Hugo S., recipient of the Iron Cross and former Bund member. This individual, working at his bench in a war plant, observed to fellow employees that 500 pregnant Waacs had just arrived in New York from overseas. A fellow worker, whose daughter was a Waac stationed overseas, promptly knocked him down and reported him. Intelligence agents made every effort to prove that Mr. S. was acting as a Nazi agent in repeating this rumor, but were unable to do so. Several weeks before, Representative Daniel S. had risen in the Massachusetts legislature to make the same charge. He alleged that the story was told him by an Army medical officer whom he refused to name, and the representative was not a Nazi agent.98

Even when a rumor could be traced to its originator, there was no legal means of punishing loyal American citizens for gossip. An Axis agent, if proven such, could have been jailed had he spread identical stories with intent to hinder mobilization. Members of the armed forces could be punished only if it could be proved that they used their position to

[215]

spread false official information detrimental to the war effort. Director Hobby reluctantly recommended such action to Waacs who reported, for example, that an instructor in an Army school had told his class that Waacs were "a prostitute Army," that an officer's wife had told everyone in a beauty shop that large numbers of Waacs were pregnant, and other such cases. Observing, "It is a bitter thing that this had to happen in the Army family," Director Hobby advised that in every such case the offender's name be obtained and a report made for investigation of the charges.99

The conclusion that Axis agents were not primarily involved was supported, after the end of the war, by captured German intelligence files. These indicated that German agents had collected newspaper clippings and other public announcements, and were well aware of the Corps' strength and the plans to recruit more womanpower, as well as of the plans to place the WAAC in the Army. However, there was no indication that the Germans had placed secret agents on this project, as they had on others; apparently they were content with information gleaned from news and radio sources. If any orders had been given to spread rumors, they were not recorded.100

It proved all but impossible for a Waac to defend herself or the Corps against the various rumors. For example, a young recruiter, in her speeches to civic groups, attempted to spike the rumors by telling the absolute truth: not that all Waacs were angels, but that only one Waac in the area had ever been picked up by military police; only one out of many drank heavily; the local police chief reported "very little trouble"; only nineteen women of thousands trained had ever been discharged for pregnancy and she "understood" that all nineteen were married. Spectators reported that "it appeared to give them more to talk about.101

At least one constructive countermeasure was put into effect by WAAC Headquarters. A planeload of the most prominent leaders of the Catholic, Jewish, and Protestant faiths had been carried to Fort Oglethorpe and Fort Des Moines for a visit shortly before the newspaper columnist's attack. They were given opportunity to inspect chapels, hospitals, clubs, and barracks, to talk to the staff and trainees, and to hold religious services. As a result, immediately after the attack, these clergymen issued a signed statement to the newspapers, saying, "We feel that parents concerned about the moral and spiritual welfare of their daughters can be reassured. A hopeful harbinger of the new world is evidenced by the sacrificial contribution which American women are making through the WAAC. [It] will strengthen their character." Monsignor Michael J. Ready told the Waacs, "We're proud of you." Dr. Carroll C. Roberts wrote the Director, "We were all deeply conscious of the earnestness of the young women and the quiet dignity with which they carried out their work.102 These statements were reinforced by articles and

[216]

CLERGYMEN VISITING FORT DES MOINES. They are accompanied by (left) Maj. Margaret D. Craighill, Col. Frank U. McCoskrie, and the Director of the WAAC.

pictures in religious magazines by a group of religious writers and editors who received a similar plane trip.103

There was also some evidence that the newspaper blasts concerning Axis sympathizers, even though mistaken in where they placed their blame, had some effect in convincing rumormongers that they might be aiding the enemy.

Congressional committees were so alarmed by the rumors that, two days after the F3 June "Capitol Stuff" column appeared, they summoned Director Hobby to appear and bring statistics on the actual cases of pregnancy and venereal disease. After seeing these, they expressed a desire to be of assistance, and suggested that the Director publish the figures and some of the actual cases of rumor spreading, to prove to the public that WAAC morality was superior to that of civilian women.104 One Congressional committee stated:

[217]

The committee wishes to express its unqualified endorsement of this organization land] feels constrained to voice its condemnation in no uncertain terms of those who malign this splendid group of patriotic women. Certainly no self-respecting patriotic American would indulge in such a cowardly, contemptible, despicable course.105

Army commanders at many stations also immediately made their stand known to

the troops; one stated to the men:

We have gained aid and help from the women of America. If we do anything to make

their lot uncomfortable or unhappy, if we fail to give them a maximum amount of

respect, if we fail to behave always as gentlemen, we have not only lost a

contribution towards winning this war, but we have also lost some of the finer

qualities of manhood.106

Others in Congress and elsewhere took the attitude that the stories were merely good clean fun and that the Waacs were spoilsports to object to them. According to a member from Alabama, WAAC stories were "like traveling salesman jokes" and he looked upon them as "the way this country keeps its sense of humor.107 General Marshall was later to suggest that responsible Army officers might be able to distinguish between clean fun and a dirty joke by asking themselves if the stories would appear equally funny if circulated about Army wives and daughters instead of about Waacs. To Director Hobby for the WAAC, General Marshall wrote:

To me, one of the most stimulating aspects of our war effort has been the

amazing development of the WAAC organization in quality, discipline, capacity

for performing a wide variety of jobs, and the fine attitude of the women themselves.

Commanders to whom the Waacs have been assigned have spoken in the highest terms

of their efficiency and value. The best evidence in the matter are the demands

now being made on the War Department for increased allotments of WAAC

organizations . . . .

I wish you would reassure your subordinates of the confidence and high respect

in which they are held by the Army.108

WAC leaders were later to conclude that the whole slander campaign had been to some degree unavoidable. In this, the British precedent of identical slander in two world wars lent strong support. One WAC leader commented, "Men have for centuries used slander against morals as a weapon to keep women out of public life." Mrs. Hobby, after a lapse of some five years, remarked, "I believe now that it was inevitable; in the history of civilization, no new agency requiring social change has escaped a similar baptism. I feel now that nothing we might have done could have avoided it.109

[218]

Page Created August 23 2002