CHAPTER XII

July-September 1943: The Conversion to Army Status

By the middle of, June 1943, after delay caused by the slander campaign, the WAC bill was at last nearing approval by Congress.1 The Auxiliary Corps faced its final and most severe test, for every member must choose honorable discharge or immediate enlistment in the new V1lomen's Army Corps, Army of the United States. Neither the modern Army nor any other women's service had ever faced such a trial, and no precedent existed as to how many of the enlisted personnel would depart when given such an opportunity.2

It had been known for some time that certain clauses in the pending WAC legislation would probably give every member of the WAAC the right to elect immediate honorable discharge rather than to enlist in the new WAC when it should be established. The Army's Judge Advocate General ruled that it did not lie within the Army's power to transfer women from the WAAC to the WAC without their consent, since only a selective service law could place a citizen under court-martial jurisdiction without his consent.3 At first, few departures had been anticipated, but in june, following the newspaper attack, Colonel Catron was obliged to inform the War Department: "It looks as though more members of the old WAAC than we had anticipated have it in mind not to join the WAC.4

Reporters and editors, sensing a spectacular story in the offing-possibly the end of the Corps itself-demanded confirmation of the fact that "the Army is very much worried about the WAAC situation." When estimates of probable losses were refused them, some intimated that they would publish estimates of their own.5

Director Hobby stated, just before the bill passed, "My feeling is that we don't want them if they don't want to stay in. I would hate to lose a great many but I would rather have a smaller Corps of women who are dedicated to this service. This is something that a woman must want to do if she stays in." 6 She therefore refused to take steps to persuade women

[219]

to stay by emotional appeals or any other means.

The WAC bill itself, as it neared passage, offered women the mixed blessing of Army status, but few other inducements. Little was left of the simple version proposed by the War Department, which would have placed few limitations on the Secretary of War's power to decide administrative matters. The Congressional situation had continued unfavorable all spring. In April the War Department became so alarmed at the rejection of the Navy bill to send Waves to foreign countries that it withdrew the WAC bill entirely and submitted it again in May.7

Even so, a number of amendments had to be accepted: the Corps was to last only for the duration plus six months; it was limited to women aged 20-50 years; its commanding officer could never be promoted above the rank of colonel and its other officers above the rank of lieutenant colonel; its officers could never command any men unless specifically ordered to do so by Army superiors; physicians and nurses could not be accepted because of the Medical Department's insistence on autonomy.8 Many even more hampering amendments had been narrowly averted the Senate's proviso that the Corps expire on 1 January 1945, and the House's attempts to limit the Corps to 150,000, to set the top age at 45, to forbid WAC officers to be assigned to Army jobs, and to deny all dependency benefits to women but all these were eventually eliminated in conference. Director Hobby stated that she was willing to accept any amendments if only the bill might pass. 9

Just as they had been a year previously, the efforts of the Army's highest authorities were required to secure Congressional approval. General Marshall urged passage of the bill in a letter to Chairman Andrew J. May of the House Military Affairs Committee, and also intervened to secure the new age limit of 20-50, which would admit more recruits than the previous 21-45 limit. General Somervell was also summoned to testify when the Military Affairs Committee seemed about to disapprove the bill because of the erroneous idea that Wacs would be used to displace Civil Service workers in Washington. This had actually been done on a large scale by the WAVES without Congressional disfavor, but never by the Army. "They've got the Waacs and the Waves confused," noted the Office of the Secretary of War.10

The bill to establish a Women's Army Corps in the Army of the United States was passed by the Senate on 28 June and

[220]

signed by the President on 1 July 1943.11 On 5 July, in the presence of General Marshall and other dignitaries, Director Hobby took the oath of office as a colonel, Army of the United States, thus becoming the first woman to be admitted to the new component of the Army. 12

The passage of the bill was the cause of general pride and pleasure to Waacs throughout the world. The commanding general of the Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation wrote to Colonel Hobby:

You would have been amused and, I think, pleased at the reaction of our personnel here to the news that the legislation had gone through. The Port Band at mess time. accompanied by a large part of our Headquarters Detachment of enlisted men, proceeded to the WAC barracks and serenaded the girls with "You're in the Army Now." and "This is the Army, Mr. Jones." and a general jollification ensued.13

Actually, "You're in the: Army Now" was somewhat premature, for the WAAC did not automatically become the WAC. The law gave the Army ninety days to arrange for the dissolution of the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps. By the thirtieth day of September, all Waacs must be enlisted or commissioned in the WAC, or discharged, for the WAAC would cease to exist.

The following ninety days of the summer of 1943, informally called The Conversion, were perhaps the busiest in the history of the Corps. WAAC Headquarters' fourteen-hour day now approached a twenty-four-hour one as WAAC officers worked throughout the night to type, sort, and fold informational material and stuff envelopes. Director Hobby canceled all travel plans for July and August. and the headquarters braced itself for three months of the most intense activity the Corps had yet experienced.14

WAAC Headquarters was immediately hit by "a flood of requests for information regarding the changeover." 15 Stations in the field had had no instructions or advice as to the nature of the conversion, and knew only what they read in the newspapers. Some stations immediately began to let women go home if they wished, without proper authority;16 others began to swear them into the Army, also without authority-in fact, some enlisted women were sworn in by WAAC officers and served for months without ever knowing that they were not in the Army. 17

Director Hobby had foreseen this confusion and had asked the War Department to permit her to send the complete conversion plan to the field far in advance of the event. This conversion plan had actually been carefully prepared over the past six months by WAAC Headquarters and The Adjutant General's Office, and included a detailed timetable based on T Day or 'transfer Day. Women who desired to transfer to the WAC must complete a

[221]

certain application form, must pass a stricter Army medical examination, and must also be recommended by their commanders. It was intended that this processing be completed by 1 September 1943, on which date Waacs all over the world would be sworn in with mass ceremonies.18

G-1 Division of the General Staff had refused the request to communicate this plan to the field in advance of the passage of legislation, stating that such action might be illegal or might adversely influence Congress, and had told the Director, "There will be plenty of time."19 The Director persisted and finally, only a week before the passage of the bill, succeeded in getting a confidential letter sent to all commands, giving an enlistment plan that could be put into effect under any probable wording of the legislation.20

On I July 1943, a few moments after the bill was signed, Director Hobby telegraphed all Army commands telling them to begin the processes of this letter, and to abide by WAAC Regulations until new ones could be published. Unfortunately, the letter itself had not yet had time to filter down to most Army stations, since it had to be relayed through several command echelons, and those women who wished to leave, and their parents, became immediately frantic for reassurance. When the Director saw how little information had reached the field, she chose six of the Corps' best officers and sent them on tour to carry correct procedures to every WAAC company; she herself visited as many as possible.21

Even after stations received instruction, the apparently simple process soon proved unbelievably complicated: all of the administrative problems of the Auxiliary here converged and demanded a final definitive solution as to the exact status of its members in all legal matters before WAAC records could be closed out. Some of these questions, but not many, could be answered by WAAC Headquarters. A number of red-bordered immediate-action letters were published by The Adjutant General, at WAAC Headquarters' request, to get answers to the field before 1 September, while others were answered by telephone and telegraph.22

In addition, there were about twenty major issues which neither the Army nor WAAC Headquarters had the power to decide; these were submitted to the Comptroller General, but decision was not received on some cases until the following October and November. Most stations desired especially to know whether WAAC service might be counted as Army service for purposes of longevity pay. Most Waacs and Army stations felt strongly that it should, since in actual conditions of daily living there was virtually no difference in WAAC and WAC life, which continued without a break in its routine. The Army Service Forces blamed the Director's

[222]

Office for the delay in answering such questions, and one of General Somervell's consultants pronounced its organization "inadequate," saying, "Simple questions such as 'Does my service in the WAAC count so far as longevity benefits are concerned?' are unanswered. It is possible that five minutes would be required to settle a question of this type; the only possible answer is yes." 23 As a matter of fact, the only possible legal answer was no, and after some years of controversy and attempted corrective legislation, the answer was still no.24

Some Comptroller General decisions decided such issues as the fact that Waacs were not entitled to re-employment rights even if they enlisted in the WAC, since they had not gone directly from their civilian jobs to the Army; this issue was not finally settled until 1946 when corrective legislation was secured. It was also found that Waacs who enlisted in the WAC forfeited their eventual travel pay home upon discharge, and were entitled only to pay to the place where they joined the Army, their present station; correction of this matter luckily did not require legislation and was made by the Comptroller General in time to prevent wholesale failure to enlist.25

Still worse field confusion resulted when the physical requirements were changed in mid-August. For two months before passage of the bill, Director Hobby had argued with The Surgeon General over the physical standards, which she wished to adjust so as to admit every Waac who had been qualified upon her enrollment and who had since given satisfactory service, even though her physical condition might have declined since her enrollment. She felt strongly that these women should be admitted to the WAC and given remedial treatment if necessary. This The Surgeon General refused, stating that routine granting of administrative waivers would negate the desired screening by virtually blanketing the WAAC into the WAC. Director Hobby especially objected to the high visual standards, seldom needed by enlisted women, and directed that her office "go to bat with the Surgeon General." Toward the end of June, G-1 Division decided in favor of The Surgeon General, and directives for physical examinations here published accordingly.

By August the numbers of Waacs rejected for physical reasons became so excessive that the decision was reversed, Colonel Hobby's plan accepted, and all discharges for physical reasons were stopped until the requirements were corrected. This action could not authorize recall of women who had already been discharged under the old standards, and considerable inequality of treatment to individuals resulted.26

[223]

Meanwhile, station commanders were alarmed to note that, during the two month period of indecision and confusion, many women who had at first intended to enlist were changing their minds. The delay between passage of the bill on 1 july and the scheduled date for mass swearing in on 1 September gave parents, friends, and former employers time to urge a return home. Moreover, Army supervisors were found to be offering certain women high civilian salaries to leave the Corps and continue in the same jobs as civilians-the advantage being, from the officers' viewpoint, that the women could then date officers and live where their quarters and hours were not supervised. This practice became so widespread that Colonel Hobby was able to collect evidence of it sufficient to secure an Army Service Forces directive forbidding such offers. Meanwhile, at stations where such transfers had already occurred, remaining Waacs were: found less disposed to continue under military restrictions and enlisted wages.27

In late July, as the evidence of suasion by relatives and employers mounted, it was directed that each station swear in its company as soon as it was ready, instead of waiting for the scheduled 1 September date for mass enlistment. Only WAAC officers were required to wait until 1 September. Where 95 percent or more of a company intended to enlist, it was suggested that a mass ceremony be held with appropriate publicity.28

This move proved successful and field companies raced to be the first to enlist. One Army Service Forces and two Army Air Forces companies tied for first place, each with 100 percent enlistment.29 Others had only a few losses, chiefly for physical disability, and throughout August these were sworn in as fast as possible.

As the WAC waited to discover what the total loss would be, it became evident that there was considerable variation from station to station-some losing none, some losing 5 or 10 percent, many about 20 percent, and others as much as 50 percent. When the loss figures from their several stations were compared, higher commanders were presented with what amounted to a chart of relative efficiency in personnel management. Air and service command headquarters at once sent inspectors and WAAC staff directors to the stations showing high losses, in the hope that conditions might be corrected while there was still time for the women to change their minds before discharge. Commanding generals of major commands became generally aware of the matter: some actually went in person to speak to the women.30

The combined discoveries of these inspectors gave WAAC Headquarters a reasonably clear picture of the reasons for which women were leaving. The most revealing discovery was that the majority was not quitting because of the hardships of Army life. On the contrary, at many

[224]

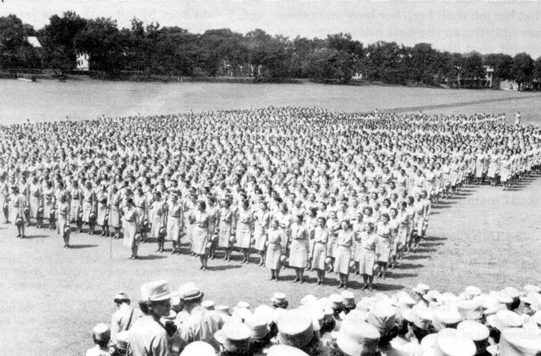

MASS ENLISTMENT CEREMONIES. Camp Atterbury, Indiana, 10 August 1943, above, and Fort 0glethorpe, 11 August 1943, below.

[225]

isolated and uncomfortable stations in deserts and swamps fewer left than at large comfortable installations. In one case, Waacs were stationed at two airfields near the same Texas city-one the handsome permanent headquarters of a commanding general, the other a hastily expanded training field; yet thirty-seven women left the first, none the second. Inspectors noted that the more isolated or less comfortable stations could not get civilians and therefore needed and appreciated the Waacs.31

One staff director reported, "The happiest girls are the ones doing the hardest work." 32 Inspectors' conclusions could be summarized in one statement: Waacs remained at stations where they were wanted and needed in their jobs. Even before the conversion started, Director Hobby had informed commands employing Waacs that only two things would be needed to make a woman wish to remain: "These are, first, that her job shall keep her busy and utilize her abilities to the best advantage, and second, that she shall feel that she is making a real contribution and that the Army is interested in her work."33

A frequently identifiable cause of loss was hostility toward Waacs on the part of a post commander, which set the tone for the entire post and was usually associated with poor job assignments for women. When Las Vegas Army Air Base lost 54 of its 151 members, inspectors reported:

The Unit Commander stated that she had met the post commander only on two occasions. Neither the Inspecting Officers nor the Staff Director was able to see him . . . . Women were assigned in the Officers' Mess and the Post Exchange. The Unit Commander has been allowed little part in the assignment of WAAC Personnel.34

At Camp Lee, Virginia, 40 of 146 were leaving. Inspectors reported:

All records were satisfactory . . . [but] morale and company spirit were found

to be very low . . . . Women stated that they did not have the proper respect of

the enlisted men. They said they had discussed this with the post c.o., but he

told inspectors he was unaware of it.35

At many other stations the fault did not lie with the post commander, except in failing to recommend removal of the WAAC commander, for inspection reports clearly placed the blame on unsuitable WAAC company commanders. At Richmond, Virginia, inspectors found records, buildings, mess, supply, recreation, and church facilities all adequate, but through the fault of the company commander many Waacs were malassigned, and "punishments have been given that are out of proportion for offenses committed."36 At Fort Monmouth, New jersey, inspectors noted: "The c.o. does not appear to have a sympathetic understanding of her troops as individuals, and many complaints were received that the EW could not readily contact her for confer-

[226]

ences."37 Another station lost 35 percent of its women because the women believed their WAAC commander to be misconducting herself with the station commander, although inspectors could find no proof of this.38 On the other hand, it was found that when companies had good WAAC commanders many enlisted in a body, even though every other outward circumstance was unfavorable.39

Many unsuitable WAC commanders were now relieved and replaced with women of understanding and integrity. Later, unsuitable WAC commanders could not be removed because the new Office of the Director WAC no longer had command power.40

When questioned, women gave various reasons for departure. Some of the more frequent excuses tabulated were:

Changed family and home conditions: "Husband now stationed in U.S. and I wish to be with him." "=Mother is ill." "Enrolled expecting husband to be drafted, but he was rejected." Almost half of the excuses given fell into this category. Some women sought leave to try to pacify relatives and men friends before giving up all hope of enlisting.

Dissatisfaction with job assignment: "Feel I can do more good in war industry." "I can do more good teaching." "My qualifications are not of as much value to the Army as they are in civilian life." "Do not feel I am doing what I came in to do." "Resent working under civilians.''

Emotional or physical difficulties: "Feel physically unfit." "Cannot accustom myself to military life." "Unable to concentrate since my husband reported missing." "My two sons killed in action. It has made me very restless." 41

Impatience with Army errors: Two women, removed from motor transport school and sent to cooks and bakers school, said, "We expected the Army to be a well-regulated organization that didn't make mistakes." Others took basic training several times, were put in the wrong specialist school, sat six weeks in staging area, and said, "We see by the papers that requests are on file for 600,000 Wacs and here we sit. What's the payoff?" 42

Other miscellaneous undesirable conditions: These were analyzed by Colonel Catron as Overstatements and unfulfillable promises by recruiting officers; inadequate physical examinations and consequent inclusion of too many physically and psycho-neurotically unfit; faulty classification and assignment; . . . some instances of assigning Waacs to jobs of less importance or dignity while civilians are used in the better positions; some cases of delay in having Waacs replace and take over the duties of soldiers and of appointing them to the grades presumably vacated by the men; . . . the public attitude that the war is all but won; the trait of women which, once they have decided to join a cause, demands that they be kept busy and that their abilities be used to the fullest; . . . recent unfavorable publicity and the indica-

[227]

tions that officers, enlisted men, and their families have not accepted the Waacs wholeheartedly, to say the least.43

Relatively fewer WAAC officers applied for discharge, although some were eliminated by a final screening board, called the AUS-WAAC Board, set up in Washington.44 The board was unable to eliminate many of the unsuitable young officers just commissioned, since they were still in the officers' pool and could hardly be rejected until they had been given a chance at one assignment. The board was also hampered by the inconsistent recommendations of some field commands, which asked that certain WAAC officers not be admitted to the WAC, but at the same time gave them excellent and superior ratings.

By this time the full extent of losses was fairly well tabulated. WAAC leaders had never ceased to predict that the majority of Waacs would not quit in spite of ample provocation. This prediction was now upheld to a surprising degree. Field stations' records of discharges were so uneven that it was not possible to determine how many of the losses were due to failure: to pass the physical examination, how many represented women whose commanders had not recommended them, and how many had actually not applied; nevertheless, the total of all such losses combined was less than 25 percent. More than 75 percent of the WAAC: had chosen to enlist and had been found physically and morally acceptable.45

Among the three major commands, the lowest average loss-about 20 percent was found in the Army Air Forces. General Arnold, during the conversion period, directed all air inspectors to make WAC job assignment a special subject, in order that "the job assigned each individual will keep her busy and employ her abilities to best advantage and that she is given an opportunity to make a real contribution." General Arnold also took personal action by appearing in a camp newsreel sequence in which he delivered a message to Air Forces Wacs, emphasizing the AAF's need of them; this was shown to all Waacs at air bases before the final dissolution of the WAAC.46

The highest losses among the three major commands-about 34 percent were suffered by the Army Ground Forces. Here, General McNair had refused to accept an AGF WAAC officer or any staff directors or WAAC specialists; he had repeatedly made known his opposition to employment of Waacs by the AGF and to the admittance of the WAAC to the Army. AGF assignment techniques had also been notably poor. In July, as manpower shortages became more serious, the AGF reconsidered its refusal to accept a WAAC staff director, and on I July Maj. Emily E. Davis, one of the first WAAC graduates of the Army's Command and General Staff School, reported to fill the position of AGF WAAC Officer, comparable to

[228]

that of Major Bandel in the AAF. Major Davis at once made a hurried series of staff visits to AGF WAAC units.

The worst situation was at Fort Knox, where she found women of the Armored Replacement Training Center, declared unassignable for lack of typing skill some three months before, still sitting in the barracks without employment. She immediately secured their reassignment to other stations to duties commensurate: with their Specification Serial Numbers. Major Davis made efforts to correct varied undesirable conditions in other WAAC units, but she had come too late to prevent extensive departures. Major Davis later noted:

The negative attitude of the command toward the utilization of women in the Army, which could not help but be transmitted to the field commanders, and through them to their staffs and to the enlisted women, had a part in this loss of personnel.47

WAAC observers had no difficulty in identifying the motivating force that had kept 80 percent of Waacs in the Army in the most friendly commands, and 66 percent even where employers were hostile. Most women felt that to leave would be moral desertion under the fire of the slanderers, and a betrayal of the ideals that had caused them to enlist. Enlistment was, like the original enrollment, ordinarily a matter of idealism rather than of logic. Observers at a training center reported that women who had asked discharge for good cause suddenly dropped their packed suitcases and ran weeping across a drill field to join their old platoons and take the oath of enlistment. Some who left soon asked to return.48 Others who did not enlist later regretted it; one wrote two years later: "If I could only have that chance again. I haven't felt fine every time I think of it." 49

Director Hobby said:

We lost a great many fine women because they could not pass the Army physical,

but we also lost a great many women who would never have been soldiers. It makes

me very happy to know that those who stayed, stayed because they know what true

obligation is, and I for one feel that what we now have is a firmer core to

build around.50

As bulwark against its inherited problems, the new Women's Army Corps had but one asset, but that an invaluable one-some 50,000 loyal members who now, in spite of full knowledge of its problems, followed the Corps into the Army of the United States.

On the first of September, 1943, eligible WAAC officers were sworn into the WAC, in grades equivalent to their WAAC grade and with date of rank the same as in the WAAC. On the same date all WAAC units were officially redesignated as WAC. By this time enlistment of enrolled women was almost complete. Instructions were issued in September for the disposition of remaining WAAC members. Throughout the month, there was considerable scurrying both in headquarters and the field as stray Waacs were rounded up.51

On 30 September, the Women's Army

[229]

Auxiliary Corps ceased to exist. For the women who chose to remain with the Women's Army Corps, Colonel Hobby suggested, and got, a green and gold service ribbon to show their WAAC service. She said:

It is probable that this period will prove to have been the most difficult in the life of the Corps and the one which, because of its pioneering aspect with all that this implies, will be the source of the greatest pride to; and the reason of the strongest ties among, the members of the WAC.52

[230]

Page Created August 23 2002