CHAPTER XI

Signaling Ahead

Over the course of 130 years the Signal Corps evolved from a one-man operation into a complex organization comprising tens of thousands of individuals. Signaling methods, likewise, underwent extraordinary changes. Myer's wigwag flags and flaming torches were replaced by radios, radar, and computers. Not only within the Army but throughout society at large, communications-or "information technology" as it is often referred to in the 1990s-had grown in size, sophistication, and influence, transforming the world into a "global village." Indeed, the pervasiveness of electronic communications is reflected in contemporary jargon which, for example, describes individuals as being "tuned in" or "on our wavelength." As the Army's voice of command, the Signal Corps played an active role in this transition, both influencing and being influenced by the process.

During the troubled years that followed Vietnam, the Army underwent a significant metamorphosis. Congress discontinued the draft in 1972, and the Army, along with the rest of the armed forces, became an all-volunteer organization the following year. Women acquired an expanded role in this new Army as their career opportunities widened. The Signal Corps opened many of its military occupational specialties (MOSS) to women and by 1976 included 7,000 enlisted women distributed among all but six of the sixty-one communications specialties. Only those jobs that might require direct participation in combat remained restricted to men.1 In 1977 Regular Army troop strength totaled just under 775,000, and approximately 7 percent of these soldiers were women. With the discontinuance of the Women's Army Corps in 1978, women became fully assimilated into the Army establishment.2

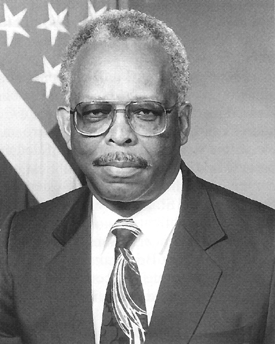

Besides women, the military also provided opportunities for members of minority groups. On 24 March 1976 Brig. Gen. Emmett Paige, Jr., became the Signal Corps' first black general officer. From 1966 to 1968 he had been deputy project manager for the Integrated Wideband Communications System, and later he commanded the 361st Signal Battalion in Vietnam. At the time of his promotion, he served as commander of the 11th Signal Group (later redesignated as the 11th Signal Brigade) at Fort Huachuca, Arizona. Nearly one hundred years had passed since the Signal Corps admitted its first black soldier, W Hallet Greene,

[391]

SIGNAL TOWERS AT FORT GORDON, GEORGIA, THE

"HOME OF THE SIGNAL CORPS"

in 1884. Paige represented a larger trend throughout the Army and the government as a whole. In 1977 President Jimmy Carter appointed Clifford L. Alexander, Jr., as the first black secretary of the Army.3

With the budget tightening that has accompanied all postwar periods, the post-Vietnam Army adopted a streamlined force structure comprising sixteen Regular Army divisions, strong enough to defend U.S. interests in Europe but lean enough to reduce the strain on taxpayers' pocketbooks. Under the new "One Army" or "Total Army" concept, the Army Reserve and National Guard assumed a greater role in the nation's defense, contributing "roundout" units to the understrength regular divisions in case of mobilization. Accordingly, the Army put much of its combat support strength, to include Signal Corps units, within the reserves.4

In July 1973 the Army placed its branch schools under the newly created Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC). The following year the Army began consolidating most of its signal training at Fort Gordon, Georgia. Consequently, on 1 July 1974 the Southeastern Signal School was redesignated as the U.S. Army Signal School, while the signal school at Fort Monmouth became the U.S. Army Communications-Electronics School. Shortly thereafter, on 1 October 1974 Fort Gordon became the U.S. Army Signal Center and Fort Gordon, the new "home of the Signal Corps."5 Because the complicated transition process took some time to complete, involving the movement of personnel, materiel, and equipment, the last class in signal communication did not graduate from Fort Monmouth until June 1976. While Fort Monmouth retained its important role in research and development related to communications-electronics, the school's relocation broke up the "troika" of the post, school, and laboratories that had existed there since World War 1.6 On the other hand, Fort Gordon's southern setting made year-round outdoor training possible, and its 56,000 acres provided enough open space for deployment of full-size units. The

[392]

school's relocation also saved money and facilitated the practice of "one station unit training" by enabling signal soldiers to receive their basic combat training as well as their advanced individual branch training at the same post.7

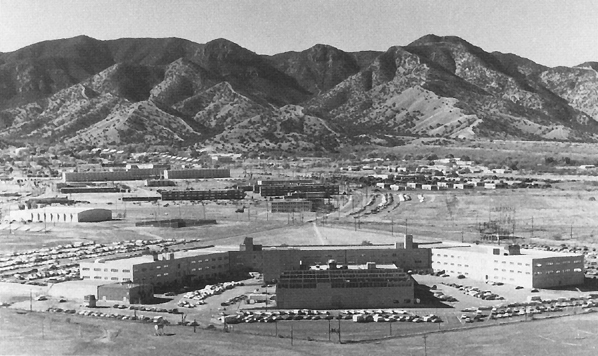

On 1 October 1973 the Strategic Communications Command, now located at Fort Huachuca, dropped the "strategic" from its name and became the U.S. Army Communications Command (ACC), a title that better described the broad range of its mission: from providing communications within Army posts, camps, and stations to signaling across the continents with satellites. In addition to providing the Army's nontactical communications, the ACC also had responsibility for civil defense communications and for managing air traffic control at Army airfields worldwide.8 The ACC divided its operations among three major subcommands: the 5th Signal Command in Europe; the 6th Signal Command in the Pacific; and the 7th Signal Command in the continental United States, Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and Panama. By 1976 the ACC comprised 30,000 military and civilian personnel in twenty nations.9

The Signal Corps and the AirLand Battle

Given the straitened circumstances after Vietnam, Army planners undertook a revision of tactical doctrine during the 1970s. Incorporating the lessons learned in Southeast Asia, the massive military buildup of the Soviet bloc, and the results of the Arab-Israeli war in 1973, the effort resulted in a new edition of Field Manual 100-5, Operations, published in July 1976. Focused upon an armor-dominated European battlefield, the new operational doctrine advocated an "active defense" that overwhelmed the enemy with massive firepower. In the face of an adversary greatly superior in strength, the strategy became one of "fighting outnumbered and winning," and victory in the first battle became all but imperative.10 This doctrine received severe criticism, however, with its departure from the traditional emphasis on offensive warfare and its narrow concentration on Europe, and it soon fell out of favor.11

Events of the late 1970s, particularly the seizure of American hostages by Iranian revolutionaries in November 1979 followed by the Russian invasion of Afghanistan in December, suggested that the Soviet Union was pursuing an aggressive foreign policy in a turbulent, unstable region where important U.S. and Western European interests-in particular access to Middle Eastern oil-were involved. Suddenly the possibility of a third world war triggered by a superpower miscalculation in the region seemed very real. In this context, a different approach in the Army's warfighting doctrine became a matter of some urgency. Consequently, the Army again revamped Field Manual 100-5 and published a new edition in August 1982. With this document the Army adopted the concept of the AirLand Battle, which returned to an aggressive strategy that stressed maneuver to keep the enemy off balance. Air and ground warfare became integrated on an extended battlefield where nuclear and chemical weapons would be used if necessary.12

[393]

AirLand Battle doctrine, however, had no impact on the one major operation in which the Army participated during the early 1980s, Operation URGENT FURY. In October and November 1983 Army Rangers, Special Forces, and paratroopers took part in a joint operation to rescue American medical students from the Caribbean island of Grenada where a bloody revolution had broken out. Hastily planned and executed, the mission encountered a host of difficulties. Communications were seriously hampered by the absence of a joint communications plan. Consequently, no provisions were made to ensure interoperability between the systems operated by each service.13 Fortunately, despite unexpected resistance from Grenadian and Cuban forces, the operation achieved its objective.

During the previous decade the Army had begun pursuing the development of such high-technology items as the M1 tank, the Patriot air defense missile, the Bradley fighting vehicle, and the Apache attack helicopter. AirLand Battle only became feasible because of the potential of these weapons systems. In turn, the doctrine drove the acquisition of those systems that would best assist in its implementation. At the same time, the Soviets had equaled and, in some cases, exceeded the United States in weapons technology. Budgetary constraints remained a problem until the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in December 1979. In the aftermath, the Carter administration initiated a massive military buildup that reached its apogee under Presidents Ronald Reagan and George Bush in the 1980s.

Modernization included communications systems designed to take the Army into the twenty-first century. For use at echelons above corps, the Army and its sister services developed interoperable telecommunications equipment through the Joint Tactical Communications Program (TRI-TAC).14 Such equipment could alleviate the problems experienced in Grenada. At division and corps level the Army adopted new tactical communications architecture known as Mobile Subscriber Equipment, or MSE. To save time and money, the Signal Corps decided to accept a system that had already been developed rather than to design a new one.

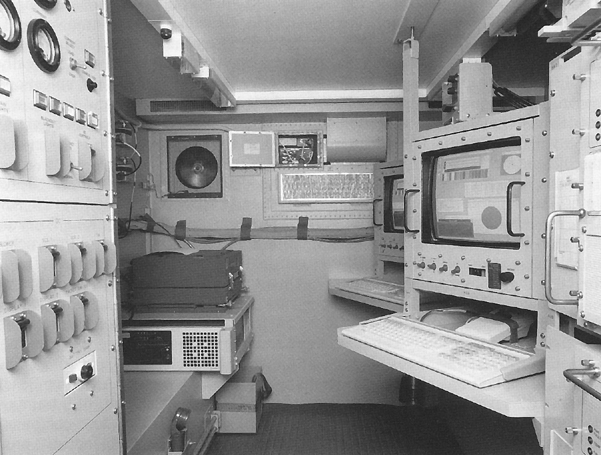

MSE, produced by General Telephone and Electronics (GTE), was a fully automatic, secure radiotelephone switching system that could be used by both mobile and static subscribers. At a cost of over $4 billion, MSE ranked as one of the largest procurement efforts ever undertaken by the Army. It consisted of an array of electronic switching nodes, voice and facsimile terminals, and radios that replaced conventional multichannel radio systems. Housed in shelters mounted on High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicles (or Humvees, the versatile machines that replaced the jeep as the Army's prime carrier) instead of in large vans, MSE was more mobile, required less wire and cable, and needed no large antennas like those commonly seen in Vietnam. Moreover, it was interoperable with existing U.S. and NATO tactical and strategic communications systems, including tactical satellites.15

Unlike communication systems then in operation, MSE was user based. The Signal Corps distributed the equipment and provided technical assistance and

[394]

INTERIOR VIEW OF SHELTER HOUSING MOBILE SUBSCRIBER EQUIPMENT

advice, but the user owned and operated it. MSE worked much like commercial telephone systems in which each subscriber received a unique directory number. Unlike commercial networks, however, the user's number in the MSE system followed that individual wherever he or she was on the battlefield. Thus, command posts could be moved without accompanying delays for rewiring-calls were automatically switched to the new location. If a node was destroyed, the system automatically rerouted messages along a new path. Just like "Ma Bell" and its competitors, MSE offered call forwarding and teleconferencing and provided facsimile transmission for record traffic and graphic materials such as maps.16

MSE was also distinctive because the fielding of the system occurred at the same time for both the active Army and the reserve components. The fielding was conducted on a corps-wide basis, beginning in 1988 with the III Corps at Fort Hood, Texas. Barring major complications, the Signal Corps anticipated that MSE fielding would be completed throughout the Army by the middle of the 1990s.17

At battalion level and below, the Signal Corps introduced new VHF-FM combat net radios. The Single Channel Ground and Airborne Radio System

[395]

(SINCGARS) was intended to replace the VRC-12 family of radios developed during the late 1950s. Available in manpackable, vehicular, and airborne versions, SINCGARS was smaller, lighter, and provided more channels than its predecessor. It also accepted both voice and data transmissions and could automatically amplify whispered messages. Moreover, it offered more secure communications because its frequency-hopping ability made it harder to locate and jam. Later models also included an integrated security device. Fielding of the sets began in 1988 with the 2d Infantry Division in Korea and was scheduled to be extended throughout the Army during the 1990s.18

Data systems developed as part of the modernization program included the Joint Tactical Information Distribution System (JTIDS) to be used by the Air Defense Artillery for missile fire control missions and the Enhanced Position Location Reporting System (EPLRS) that used radios to provide real-time position location, identification, and navigational information on the battlefield. Together they comprised the Army Data Distribution System (ADDS).19

Training soldiers in the operation of these sophisticated systems remained an essential component of the Signal Corps' mission. Moreover, as communications systems grew increasingly complex, more training became necessary. Nearly all Signal Corps training, both officer and enlisted, took place at Fort Gordon. A notable exception was photographic training, conducted at Lowry Air Force Base, Colorado. As part of its contract with the Army, GTE conducted all MSE training and operated a resident school at Fort Gordon. The Signal Corps also continued to work closely with the private sector through the Training with Industry program. This Army-wide program provided officers with education and experience applicable to their assignments by allowing them to work with civilian industry for a year. Among the participating corporations were AT&T, Boeing, GTE, and Kodak.20 In 1984 the Signal Corps established ROTC affiliation programs at several universities, among them Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and the Georgia Institute of Technology, in an effort to increase the recruitment of officers with technical backgrounds.21

Organizational changes also accompanied the Army's doctrinal adjustments. During 1978 the Army initiated the "Division 86" study to modify the ROAD configurations. Consequently, the Army designed "heavy divisions" to fight against the massive mechanized and numerically superior forces of the Soviet Army and allied Warsaw Pact armies. These restructured units would also incorporate the new weapons and equipment under development. The resulting heavy divisions each comprised six tank and four mechanized battalions, and divisional aviation assets became centralized within aviation brigades. The divisional signal battalions, however, did not differ significantly in structure from their ROAD counterparts.22

In addition to the heavy divisions designed to fight a conventional war, the Army in the 1980s organized light divisions for fighting limited wars wherever they might occur. Containing about eleven thousand soldiers, compared to seven teen thousand for a heavy division, these smaller units were easier to transport

[396]

and thus better suited for rapid deployment.23 To retain combat power, the divisional support elements were sharply reduced in size. The signal battalion's strength, for example, was pared from 784 soldiers to 470.24

In 1981 Army Chief of Staff General Edward C. Meyer approved the implementation of the United States Army Regimental System (USARS) to improve unit cohesion and esprit. As part of the new manning system, soldiers were assigned to regiments and, as originally conceived, would remain affiliated with them throughout their military careers. Within the Signal Corps and other combat support/combat service support branches, where a large portion of the soldiers served in units outside their assigned branch, the system was implemented on a "whole branch" basis. In other words, the entire Signal Corps was considered to be the Signal Corps regiment, and any soldier with a Signal MOS was automatically affiliated with the regiment upon graduation from the branch school. On 1 June 1986 the Signal Corps regiment was established as a component of the USARS with Fort Gordon as the regimental home base. Accordingly, on 3 June 1986 the commander/commandant of the Signal Center and Fort Gordon also became known as the chief of signal. Maj. Gen. Thurman D. Rodgers became the first to carry the new title.25

The Signal Corps tested the progress of its modernization efforts during Operation JUST CAUSE in 1989. Tensions between Panama and the United States had been building since the rise to power of General Manuel Antonio Noriega during the 1980s. Noriega's regime initiated a campaign of harassment against American civilian and military personnel, and the United States imposed economic sanctions in an effort to depose him. The situation worsened following the fraudulent presidential election of May 1989 and an unsuccessful coup attempt in October of that year. Consequently, the United States undertook extensive contingency planning for a possible intervention to protect American lives, uphold the Panama Canal treaties, and restore democracy to the country. In addition, the United States government had indicted Noriega in 1988 for drug trafficking and other crimes. Thus, as violence against Americans escalated, the stage was set for military action.

The United States launched JUST CAUSE on 20 December 1989. Early that morning the 82d Airborne Division parachuted into Panama. Members of the 82d Signal Battalion participated in this assault. The battalion's drop was somewhat off center, however, and the men landed in a swamp. Despite being burdened with up to 100 pounds of equipment each, the communicators worked quickly to establish the required communication nets.26

Although most of the units involved in the invasion belonged to the Army, the Air Force, Navy, and Marines also participated in JUST CAUSE. In the communications arena, this joint operation ran much more smoothly than URGENT FURY for a number of reasons. Signal Corps representatives took part in the operational planning and helped develop joint communications-electronics operating instructions. Prior to the assault, U.S. forces conducted extensive training exercises in Panama that prepared them for the actual event. Thanks to the presence of TRI-TAC

[397]

equipment, interoperability did not pose a problem. Unlike Grenada, the Signal Corps could take advantage of the fixed-communication facilities already in place. Fortunately, Noriega's forces did not seriously attempt to disable the strategic communications network.27

On 3 January 1990 General Noriega, who had taken refuge in the Vatican embassy on Christmas eve, surrendered to U.S. officials. He was subsequently taken to the United States to stand trial. As the situation in Panama stabilized, the United States gradually withdrew its invasion forces, and Operation JUST CAUSE officially ended on 31 January 1990.

Communications can be defined as a process or system of conveying information. In 1915 Chief Signal Officer George P Scriven recognized this connection between communications and information when he published a manual entitled The Service of Information in which he outlined the scope and purpose of the Signal Corps. As Europe became embroiled in World War I, advances in the science of warfare made rapid and reliable communications increasingly valuable to the commander. As Scriven remarked: "Without information and knowledge of events and conditions as they arise, all else must fail." Moreover, "without an adequate service of information" troops would have "rather less direction and mobility than a collection of tortoises.”28

In recent decades automation has had a tremendous impact upon communications. These two fields have become increasingly interdependent and may soon become indistinguishable. In fact, by 1978 the former chief of communications-electronics had become the assistant chief of staff for automation and communications.29

In accordance with this trend, during June 1983 Army Chief of Staff Meyer initiated a major realignment in the way the Army managed its information resources.30 His successor, General John A. Wickham, Jr., carried out the detailed planning of this process. Taking a broad-based approach, he combined five information-related functions, or disciplines (communications, automation, visual information, publications/printing, and records management), into what he called the Information Mission Area (IMA). Correspondingly, the Army Communications Command became the Army Information Systems Command on 15 May 1984, incorporating the A

rmy Computer Systems Command and several smaller elements, in order to centralize communications and the IMA under one administrative umbrella. Lt. Gen. Clarence E. McKnight, Jr., organized the new command, but led it only briefly, being assigned to the Pentagon in July 1984. He was succeeded by Lt. Gen. Emmett Paige, Jr.31 At the same time, on the Army staff level, the assistant deputy chief of staff for operations and plans for command, control, communications, and computers (formerly the assistant chief of staff for automation and communications) became the assistant chief of staff for information management.32

[398]

GENERAL PAIGE

While the Information Systems Command implemented the IMA throughout the Army's strategic systems and sustaining base (posts, camps, and stations), TRADOC in 1985 assigned to the Signal Center proponency for integrating IMA doctrine at the theater/tactical level. On the modern battlefield decisions had to be made in minutes, not in hours, and instantaneous communications made this possible. The purpose of the IMA was, therefore, to quickly give the commander the information he needed to make accurate decisions and the ability to put them into effect once they were made. The broadened scope of signal support of battlefield command and control under the IMA was outlined in Field Manual 24-1, Signal Support in the AirLand Battle, first published in October 1990.

Moreover, the proliferation of automated systems on the battlefield created increasing requirements for communications. For example, the Tactical Fire Direction System (TACFIRE), which used digital computers for field artillery command and control, needed communications equipment to relay data back to the commander. It was up to the Signal Corps to integrate these automation and communication networks.

Under the IMA, photography continued to be one of the Signal Corps' primary missions, now subsumed within the discipline of visual information. This category encompassed not only still and motion photography, but also television, videotaping, and manual and computer graphic arts. The growing number of video teleconferencing centers at Army installations constituted yet another aspect of this mission.33 Meanwhile, the Army Visual Information Center in the Pentagon continued the work begun by the Signal Corps' photographic laboratories in Washington in 1918. Although it had undergone numerous name changes and realignments du

ring its history, including a period under Department of Defense control, the Visual Information Center (formerly the Army Photographic Agency) in 1984 found itself once again under Signal Corps auspices as an agency of the 7th Signal Command, which had its headquarters at Fort Ritchie, Maryland. To supplement organic photo support within field units, the center's Combat Pictorial Detachment, stationed at Fort Meade, Maryland, dispatched teams to document Army operations worldwide. Increasingly, joint combat camera teams performed combat photography. Composed of Army, Navy, Air Force,

[399]

and Marine personnel, these units deployed during both Operations URGENT FURY and JUST CAUSE. Because the Army lacked sufficient photographic support, the Signal Corps began planning for the addition of TOE visual information units to the force structure.34

Probably the most difficult functions to integrate into signal doctrine were the areas of records management and publications/printing, duties traditionally performed by the Office of The Adjutant General.35 As the Army's new records manager, the Signal Corps moved toward an electronic, paperless system. Eventually, electronic storage and retrieval of documents will be instituted on an Army-wide basis.36 In 1988 the Army's Publications and Printing Command became a subcommand of the Information Systems Command. Its two distribution centers, in Baltimore and St. Louis, were responsible for storing and distributing the Army's forms and publications, including this book.37 Moreover, in 1988 the Army Computer Science School, formerly a part of the Adjutant General School, moved from Fort Benjamin Harrison, Indiana, to Fort Gordon where it continued to provide training for computer programmers, operators, and managers. This transfer centralized education for both the automation and communications disciplines at one location.38

The development of IMA doctrine and its implementation by the Signal Corps proved to be complicated and did not occur overnight. As the Corps' history has shown, the field of military communications is constantly evolving and presenting new challenges. There is little doubt, however, that the Signal Corps will continue to adapt to changing conditions in the communications environment.

With technology changing so rapidly, the variety of communications systems and techniques that the Signal Corps had available or under development in the early 1990s seemed infinite. However, a brief look at a few of the most noteworthy suggests some of the diversity and complexity involved.

Fiber optics is one of the most notable new communication mediums that has found widespread application in the almost two decades since the end of the Vietnam conflict. Fiberoptic systems transmit information via beams of light (i.e., lasers) rather than by electrical impulses. Fiberoptic communications possess many advantages over electrical and electronic signals. Fiberoptic cables, made of glass rather than wire, are significantly smaller and lighter than coaxial cables and can carry more information. Moreover, the fiberoptic signal

s, which are transmitted in digital form, are not susceptible to jamming, electronic interference, the weather, or cross talk. They are also less vulnerable to the effects of the electromagnetic pulse (EMP), or power surge, that accompanies nuclear explosions and literally burns out metallic wires. The semiconductors used in computers are particularly sensitive to the EMP. Since the effects can be felt hundreds, even thousands, of miles from where a burst occurs, communications could be disrupted over an extensive area. Fiberoptics, with its immunity to such

[400]

hazards, is thus highly suitable for military communications.39 Commercial telephone systems already made substantial use of this technology by the early 1990s. Even undersea cables are now fiberoptic. Because optical fiber can simultaneously carry multiple types of signals (e.g., phone calls, television, facsimile), such fibers will likely replace the complex of wires that enter private homes as it becomes economically feasible to do so.40

The development of superconductors represents a promising new direction for communications. These materials offer no resistance to the passage of electric current, thus holding out the possibility of much more efficient electronic devices. Technical problems remain, but the potential is great for their use in the next century.41

During the Reagan administration, the military's role in space expanded under the Strategic Defense Initiative, popularly known as "Star Wars." In 1988 the Army reorganized its space efforts by creating the U.S. Army Space Command. While in the short term the Signal Corps continued to be responsible for operating the Army's portion of the Defense Satellite Communications System (DSCS), the new Space Command gradually assumed those duties.42

Meanwhile, on the battlefield itself, manpackable tactical satellite (TACSAT) radios became available and were especially useful for low intensity conflict and for Ranger and Special Forces units. Signal units, notably the 82d and 127th Signal Battalions, used single-channel TACSAT in Panama during Operation JUST CAUSE. These UHF signals could be easily detected, however, and the satellite readily jammed by the enemy. There was also a shortage of available satellite channels. Lightweight, multichannel TACSAT had not yet been fielded by the early 1990s, and similar high-frequency radios also awaited development.43

While the plethora of electronic devices used by the Army facilitate command and control, they also have introduced a host of problems. Besides crowding the frequency spectrum, such devices are extremely vulnerable to the electro magnetic pulse. Moreover, they present a serious security risk because their electronic signatures invite enemy interdiction. With the development of such items as micro vacuum tubes, that are not susceptible to the effects of the electromagnetic pulse, this danger can be reduced.44

Despite the sophistication of modern technology in the early 1990s, the telephone remains the Army's most commonly used medium for routine administrative and logistical communications. For the foreseeable future at least, Signal Corps "cable dogs," or pole climbers, will continue to be a familiar sight both on and off the battlefield.45 The advance of cellular technology holds the promise that soldiers may eventually be able to communicate with something similar to the wrist radio familiar to readers of the old "Dick Tracy" comic strip.46

Although Army communicators of the future will be using methods unimaginable at present, they will still be doing essentially the same job as the signalmen at Allatoona, OMAHA Beach, and Phu Lam. "Rugged, reliable, and portable" signaling equipment will be as important to them as to their predecessors, and they will continue to search for the ideal field signaling device.

[401]

In August 1990 the United States launched its largest military operation since Vietnam, the deployment of over five-hundred thousand troops to the Persian Gulf. Following Iraq's invasion of Kuwait on 2 August, the United States moved quickly to protect its interests in the region. Using bases belonging to its ally Saudi Arabia the United States began the logistical buildup known as Operation DESERT SHIELD. General H. Norman Schwarzkopf, commander in chief of the U.S. Central Command, was in charge of U.S. forces. Meanwhile, the United Nations imposed economic sanctions upon Iraq, and its Security Council condemned the invasion. In addition, a coalition of approximately thirty nations joined the United States in opposition to the Iraqi dictator, Saddam Hussein.47

At the beginning of the conflict the U.S. military had just two leased telephone circuits and two record traffic circuits in Saudi Arabia. Automation support was nonexistent. As part of the buildup, the 11th Signal Brigade installed a state-of-the-art communications network. By the end of August the brigade was running the largest common user data communications system ever present in a theater of operations. This network enabled automated processing of personnel, financial, and logistical information. Data traffic in and out of the combat zone averaged ten million words a day. By November, when the brigade had completed its deployment to the Gulf, communication capabilities included automated message and telephone switching; satellite, tropospheric, and line-of-sight radios; and cable and wire lines. Fifteen voice and five message switches supplied communications support to more than ninety locations throughout the theater.48

The 11th Signal Brigade grew to include five signal battalions and two companies. In early November the brigade's assigned battalions, the 40th and 86th, had deployed from Fort Huachuca. They were joined by the brigade's 19th Signal Company, which furnished the necessary communications and electronics maintenance capability. In addition, the brigade was augmented by three other signal battalions: the 44th and 63d from Germany and the 67th from Fort Gordon. Rounding out the communications support to echelons above corps level was the 653d Signal Company, a unit of the Florida Army National Guard. It arrived in January 1991 to provide troposcatter communications.49

On 4 December 1990 the Department of the Army activated the 6th Signal Command at Fort Huachuca.50 Deploying to Saudi Arabia later that month, its mission was to administer the theater communications network. The command helped to establish frequency management, which had been a problem during previous joint operations. Moreover, the Saudi government had no central office that controlled frequency assignments.51 In March 1991 the 54th Signal Battalion was formed to provide IMA support for the theater. With headquarters in Riyadh, it comprised three subordinate companies: the 207th stationed in King Khalid Military City, the 550th in Dhahran, and the 580th in Riyadh.

To conduct offensive operations, the U.S. Army ultimately sent two corps to

[402]

FORT HUACHUCA, ARIZONA, HEADQUARTERS OF THE U.S. ARMY INFORMATION SYSTEMS COMMAND.

GREELY HALL IS IN THE FOREGROUND WITH THE HUACHUCA MOUNTAINS IN THE DISTANCE

Saudi Arabia. The first units to be deployed belonged to the XVIII Airborne Corps, the Army's designated contingency force. Based at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, the corps was supported by the 35th Signal Brigade. Both during and after deployment the brigade maintained a permanent satellite link with Fort Bragg, allowing it to support corps assets at home as well as those in the combat theater. Providing communications coverage over an area of more than 120,000 square miles in northern Saudi Arabia and southern Iraq, the brigade installed 169 separate communications systems as well as 400 miles of wire and cable and approximately five hundred telephones.52

The VII Corps began moving from Germany to Southwest Asia in November 1990. Its 93d Signal Brigade encountered difficulties during deployment when its equipment was dispersed among twenty different ships. Unlike the 35th Brigade, the 93d was not trained or equipped for service in an austere environment. Once it became fully operational, the 93d supplied communications between the corps headquarters, five divisions, and an armored cavalry regiment across an area covering more than 75,000 square kilometers. To accomplish this formidable task, the brigade was augmented by the 1st Signal Battalion, the 235th Signal Company, and the 268th Signal Company.53

In a region with a limited telecommunications infrastructure, satellites proved essential to successful operations. They formed the backbone of both tactical and strategic communication systems, providing the connections between widely dis-

[403]

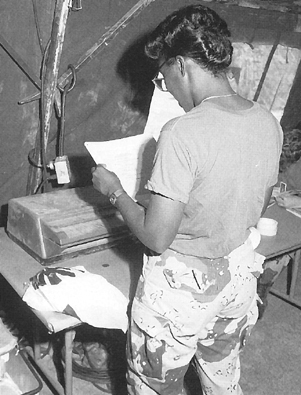

SOLDIER OPERATES TACTICAL FACSIMILE MACHINE

persed units as well as furnishing circuits back to the United States. Due to a shortage of military satellites, the Army leased circuits from commercial satellites. Satellites were also used to provide information about weather, terrain, and location. The network of satellites known as the Global Positioning System (GPS) broadcast navigation, positioning, and timing signals. This information made maneuver possible in the featureless desert environment. Fortunately, the Iraqis did not, and perhaps could not, jam these vital space-based signals.54

The U.S. Army Information Systems Engineering Command, based at Fort Huachuca, installed an electronic mail (E-mail) system that allowed soldiers to correspond with family and friends. The system handled approximately fifteen thousand such messages each day in addition to its heavy load of official traffic. As in the past, the Military Affiliate Radio System provided its services. Commercial communications systems augmented military networks, particularly for sending messages between Saudi Arabia and the United States. Corporations such as AT&T and MCI provided facilities that allowed soldiers to phone home at reduced rates.55

After five months of sanctions and diplomatic efforts, Saddam Hussein had not bowed to international pressure. When the 15 January 1991 deadline set by President George Bush for Iraq's unconditional withdrawal from Kuwait passed without compliance, war became all but inevitable. On 17 January America and its allies launched offensive operations, known as DESERT STORM. On that date U.S., Saudi, British, French, and Kuwaiti aviators began bombing military targets in Iraq and Kuwait. Following six weeks of aerial bombardment, the ground war began on 24 February. It was surprisingly short, lasting just 100 hours. The coalition forces liberated Kuwait City on 27 February, and fighting ended the following day. In early March the United States began withdrawing its troops, and by midsummer most combat units had returned to their home stations.

The Gulf conflict strikingly demonstrated the power of modern communications techniques. During Vietnam television brought reports of the war into

[404]

MOBILE SUBSCRIBER EQUIPMENT IN THE DESERT; BELOW, SATELLITE ANTENNA DISH AND

CAMOUFLAGED VANS

[405]

America's living rooms each evening, but these news accounts lagged behind events. This time cameras took viewers directly to the action. Those tuned to the Cable News Network, for example, witnessed the bombing of Baghdad as it was happening. Even the president confessed that he received much of his information from such live broadcasts. While the military exercised tight control over the flow of information to the press, televised displays of duels between Patriot and Iraqi Scud missiles and scenes of dense clouds of smoke from burning oil wells made lasting impressions upon viewers.

While the broadcast networks kept citizens informed of the war's progress, combat cameras used the latest video technology to instantly transmit images to the Joint Combat Camera Center in the Pentagon. Still pictures could be sent electronically via transceivers in less than three minutes, but technology did not yet allow motion video to be transmitted in this manner. Instead, camera crews used commercial satellite transmitters to relay motion pictures. The rapid response time enabled local commanders and high-level decision makers to use the photos immediately for operational briefings and to make damage assessments. Video cameras aboard aircraft, for example, captured the amazing accuracy of precision-guided missiles.56 Photos sent by courier or mail, however, did not arrive at the Pentagon for up to fifteen days. Although not timely enough to be used for operational planning, they provided valuable documentation of the conflict.

The Army remained, however, without its own photographic units, and there was a shortage of trained personnel. Moreover, the new field manual governing visual information, FM 24-40, had not yet been published. The Combat Pictorial Detachment at Fort Meade furnished combat camera teams to the theater-wide joint combat camera team (JCCT). In turn, joint combat camera detachments from the JCCT were deployed throughout the theater. At the peak of operations nearly two hundred combat camera personnel from all the services were assigned to the JCCT, with the Army contributing roughly 19 percent of the totals.57

When the Gulf crisis erupted, the Army had not completed the fielding of MSE. The XVIII Airborne Corps had not yet received the new equipment, and the VII Corps was still in transition; only two of its five divisions had completed the MSE fielding process. The 57th Signal Battalion from Fort Hood arrived in the theater in September 1990 to provide MSE support for the XVIII Corps.58 In Germany, the 3d Armored Division had only recently conducted field exercises with the new system. Nevertheless, the 143d Signal Battalion and its MSE were soon on their way to the Gulf. The equipment proved equal to the task, however, as it received its battle testing in the harsh desert environment. As in Vietnam, civilian technicians worked alongside the soldiers to keep the equipment functioning despite the intense heat and fine, powdery sand. Innovative communicators found that panty hose made an effective sand screen.59 MSE played a key role, enabling commanders to stay in touch with their units even during the rapidly moving offensive phase.60

Due to the presence of several generations of equipment in the field, interoperability posed a potential obstacle. At echelons above corps, the TRI-TAC

[406]

equipment allowed the Army to communicate with its sister services. TRI-TAC switches could also handle both analog (nondigital) and digital signals. MSE, on the other hand, had not been designed to interface with the older, analog systems still in use. Consequently, the Signal Corps sought various solutions to enable voice and data communications to be carried across the various networks. While reliable voice communications were achieved, data transmission remained problematical. Further technical challenges were presented by the equipment used by allied forces, such as the British Ptarmigan and the French RITA systems.61

The SINCGARS proved itself in the desert where it achieved a mean time between failures rate of 7,000 hours, compared to the 200 to 300 hours experienced by the VRC-12 radios it replaced. Patriot firing batteries used these radios for tactical communications as they defended against Scud attacks. Special operations forces employed them because of their light weight and security features. Approximately three hundred Army and four hundred Marine SINCGARS radios were in use during DESERT STORM.62

In addition to its traditional communication functions, the Signal Corps coped with its new responsibilities under the IMA. Because the relevant doctrine was not yet fully established, a number of complications resulted. Although Information Services Support Offices had been authorized at theater, corps, and division level to manage the duties formerly belonging to the adjutant general, they had not yet been created when the Army deployed to the Gulf.

To provide printing and reproduction support in the theater, the Corps sent the 408th Signal Detachment, an Army Reserve unit from New York State, to Saudi Arabia in December 1990. To perform its mission, the 408th took with it approximately $250,000 worth of state-of-the-art printing equipment. The 408th's personnel had not been trained to repair the new equipment, however, and they had difficulty obtaining supplies through regular channels. Therefore, the unit had to rely on local sources for support. Despite these problems, the 408th succeeded in doing its job.63

The Signal Corps was now also responsible for providing high-volume forms and publications, such as enemy prisoner of war tags, combat award certificates, and maintenance manuals. Without established procedures for governing this type of support, many units relied on their home station stockrooms. This procedure strained the resources of the Army Postal Office system, which was not designed to move such items to a theater of operations. Once received, distribution of the material posed further problems because no one had been assigned this duty.64

DESERT STORM confirmed the pervasiveness and power of electronics on the modern battlefield-not only for communications but in all aspects of combat. While high-technology weapons grabbed the headlines, the press contained relatively little information about military communications. But the very absence of such stories emphasized the fact that the signaling systems worked well enough that they could generally be taken for granted. At the end of 1992 it was still too soon for the Signal Corps to have fully evaluated all the lessons learned, but it appeared that its success in the conflict validated the changes in training, doc-

[407]

trine, and equipment implemented after Vietnam. In turn, the Signal Corps would apply the lessons learned in Southwest Asia toward the further refinement of its doctrine for future operations.

In the aftermath of victory, the Army underwent the usual postwar readjustments, but the process was magnified by the dramatic changes in the world resulting from the end of the Cold War. The era of glasnost and perestroika in the Soviet Union had led to the initiation of arms control and force reduction discussions between the Warsaw Pact and NATO even before the dramatic unfolding of events in Eastern Europe in late 1989. In November 1990 the two opposing blocs signed a history-making arms control agreement. The reunification of Germany and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union radically changed the geopolitical landscape of Europe. As longstanding tensions eased, the United States accelerated the pace of scheduled troop withdrawals. The need to maintain a large Army in Europe to counter the Soviet threat appeared to have greatly diminished. The VII Corps and its 93d Signal Brigade returned to Germany from their success in the desert only to be inactivated less than a year later. In 1992 the Army leadership anticipated that by 1995 the Regular Army would contain just twelve active divisions, down from eighteen, based primarily in the continental United States. Thus the Army would, they thought, spend the next decade making the transition from a forward-deployed force to one that projected power wherever needed on a contingency basis.

The Signal Corps of the early 1990s was a very different organization than that founded in 1860 by Albert J. Myer. The Army's first chief signal officer would undoubtedly find fascinating, if somewhat baffling, the evolution of signaling as he knew it to encompass telecommunications, computers, and satellites. Yet despite the changes in form, some basic similarities still existed. Myer's two-element code, for example, is amazingly similar to the binary code, the concept underlying computers. The Signal Corps' close ties with the civilian and international scientific communities and with the commercial firms that had often worked side by side with the Corps to pioneer communications technology were also similar, if more elaborate, to those that Myer had initiated during and after the Civil War.

Moreover, throughout its history the primary mission of the Signal Corps remained constant: to provide the Army with rapid and reliable communications. For many years, however, the Signal Corps' place within the Army's structure had been tenuous. Originally intended to exist only through the end of the Civil War, Congress renewed the Corps' lease on life in 1866. Nevertheless, Chief Signal Officer Myer and his successors faced an uphill battle for institutional survival. Commanders such as Sherman and Sheridan questioned the need for a separate Signal Corps during the 1870s and 1880s. Before the rise of high technology, communications was not recognized as a specialized skill. Fortunately, the Signal

[408]

Corps escaped extinction at the hands of the Allison Commission and went on to render distinguished service at home and abroad. More than ever, as its contributions to the Persian Gulf victory illustrated, the Signal Corps' status within the Army is secure at the end of the twentieth century. Every day, at locations around the globe, signal soldiers operate the communications networks, both strategic and tactical, that constitute the Army's "nervous system." These dedicated men and women preserve the Signal Corps' proud traditions and uphold its motto, Pro Patria Vigilans (Watchful for the Country). Whether by wigwag or radio, heliograph or satellite, flaming torch or computer, the Signal Corps gets the message through in peace and in war.

[409]

Return to Table of Contents