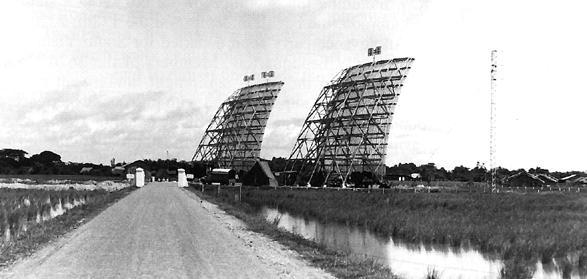

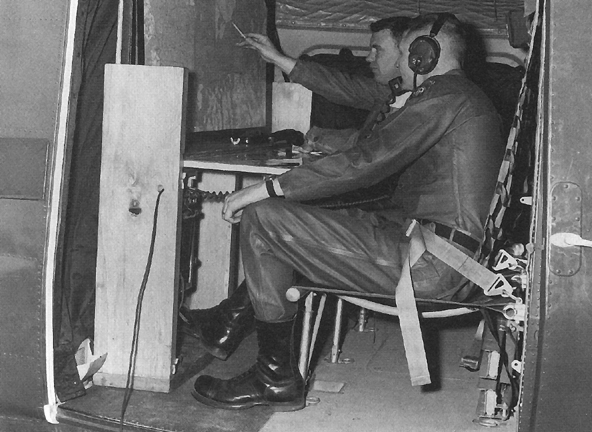

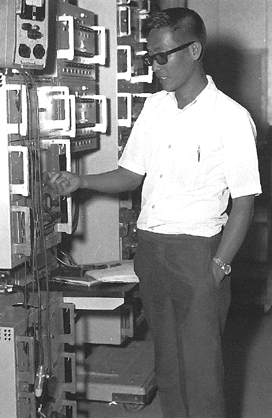

CHAPTER X The Vietnam Conflict The Signal Corps that fought the war in Vietnam differed in significant ways from the Signal Corps that had fought in conflicts from the Civil War through Korea. The chief signal officer had disappeared from the organizational chart and had been replaced by a chief of communications-electronics with no operational responsibilities. The traditional Signal Corps functions continued to be performed, however, by Signal Corps units in the field. Though its form may have changed, the spirit of the Signal Corps lived on in the soldiers who wore the crossed flags and torch insignia. While Army communicators put their technology to the test in Vietnam, the technology on trial represented the culmination of a century of effort in the field of military communications. The Origins of American Involvement French colonization of Indochina began in the 1850s, but American military involvement in the region dated from World War II when Indochina was occupied by the Japanese. After the war, with the threat of Communist domination looming over Asia, the United States offered to help France resist a Communist rebellion in Vietnam led by Ho Chi Minh. By assisting France in Asia, the United States sought to ensure French support for the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Some American strategists also warned that if Indochina fell to the Communists, the rest of Southeast Asia would follow-the concept that became known as the domino theory. As part of its assistance, the United States sent Signal Corps advisers to Vietnam to monitor the distribution and use of communications equipment and to establish an Army Command and Administrative Network (ACAN) station in Saigon. President Eisenhower, wishing to avoid another Korean-style conflict, refused either to intervene directly in the fighting or to authorize the use of atomic weapons. Defeated by Ho's forces at Dien Bien Phu in May 1954, the French agreed to a cease-fire. The truce agreement, known as the Geneva Agreements, divided Vietnam at the 17th Parallel with a Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) marking the border. As in Korea, a Communist government led by Ho Chi Minh ruled in the north, with its capital at Hanoi, while a nominal republic under President Ngo Dinh Diem governed in the south, with its capital at Saigon.1 Following the French withdrawal from Indochina, a U.S. advisory group remained behind to assist the South Vietnamese Army which, like its American [359] counterpart, contained a signal corps. Because the French had handled both civil and military communications, however, the Vietnamese had acquired little technical expertise. American signal advisers were assigned down to divisional level and to each of the country's military regions to provide training, operational, and logistical support. Since the advisory group had no staff signal officer, the signal staff of the Pacific Command, based in Hawaii, conducted most of the operational planning for South Vietnam. The U.S. Army Signal Corps sent training teams to Southeast Asia, and many South Vietnamese officers received instruction at Forts Monmouth and Gordon. Logistical signal support proved particularly difficult due to the language barrier and the lack of familiarity on the part of the South Vietnamese with modern electronic equipment and proper inventory methods. Moreover, the French had removed much of the American-supplied signal equipment, leaving South Vietnamese field units in dire straits. In addition, the commercial communications networks built by the French lay in disrepair after years of war. To provide a permanent communications system to serve the civil, military, and commercial needs of Southeast Asia, the United States hired contractors to construct a regional telecommunications network to link South Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, and Thailand. Unfortunately, the project encountered a host of problems and took years to complete. Meanwhile the Viet Cong, the Communist organization that remained in the south after the truce, stepped up its guerrilla movement against President Diem. In July 1959 an insurgent attack on a U.S. advisory detachment at Bien Hoa killed two Americans and wounded another. In rural areas, where local security forces often lacked the communications to alert the army to the presence of Viet Cong military movements, Communist domination spread rapidly. Despite the guidance received from the American advisers, the South Vietnamese Army proved incapable of coping with the situation. By 1960 Saigon's ability to control the countryside was heavily contested. As the crisis in Southeast Asia deepened, communication methods between the United States and South Vietnam remained extremely vulnerable. A single undersea cable linked the Pacific Command in Hawaii with Guam, but this connection did not extend to Southeast Asia. Thus the Army depended upon high-frequency radio, a medium that could be easily jammed. To improve matters, the Army called upon a new technique, known as scatter communications. This method worked by bouncing high-frequency radio beams off the layers of the atmosphere, which reflected them back to earth. One type, tropospheric scatter, bounced signals off water vapor in the troposphere, the lowest atmospheric layer. A second method, ionospheric scatter, bounced the signals off clouds of ionized particles in the ionosphere, the region that begins about thirty miles above the earth's surface.2 Using special antennas, both methods provided high-quality signals that were less susceptible to jamming than ordinary radio. Unlike microwave relays, scatter communications did not require a line of sight between stations. Tropospheric relay stations could be as much as 400 miles apart, compared to about 40 miles for microwave stations, a decided advantage when operating in hostile territory.3 [360] BILLBOARD ANTENNAS OF THE BACKPORCH SYSTEM AT PHU LAM IN 1962 In May 1960 a private firm, Page Communications Engineers, began building the 7,800-mile Pacific Scatter System for the Army along the island chain from Hawaii to the Philippines. From there, the Strategic Army Communications Network system made the final jump to Indochina.4 Unfortunately, STARCOM's radio circuits proved highly unreliable in the tropical environment. Consequently, in 1962 the Joint Chiefs of Staff approved plans to build a military submarine cable system, known as WETWASH, from the Philippines to South Vietnam. In the meantime, the Army installed radio links westward from Bangkok to Pakistan and eastward from Saigon to Okinawa. Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara approved, in January 1962, the installation of troposcatter equipment within South Vietnam to provide the backbone of a strategic network known as BACKPORCH, which would connect five major cities in South Vietnam with Thailand. Because the Army had little experience with tropospheric equipment, Page Engineers installed BACKPORCH at a cost of $12 million, and the company agreed to operate and maintain the system for a year. Huge "billboard" relay antennas began to appear on mountaintops. Spurs of the system would reach into the field where tactical units used standard Army multichannel radios. At the tails, or extensions, of the system, the advisory detachments at remote sites in the interior were to be equipped with the newly designed and untested troposcatter radios. In February 1962 the United States established a unified headquarters, the U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), to coordinate the expanding American military effort in South Vietnam. Meanwhile, the U.S. Army, Pacific, created a subordinate command to MACV, the U.S. Army Support Group, Vietnam, to control the Army's logistical support elements, including signal units. The 39th Signal Battalion received the mission of providing communi- [361] cations support to MACV, including the operation of the BACKPORCH stations. With headquarters at Fort Gordon, the battalion comprised the 178th, 2324, and 362d Signal Companies. An advance party soon departed for South Vietnam to operate a switchboard for MACV headquarters. Members of the 362d Signal Company, the unit assigned to run the tropo equipment, underwent several months of training at Fort Monmouth, supplemented with practical experience at factories and testing grounds, before joining the rest of the battalion overseas. As communications responsibilities increased throughout South Vietnam during 1962, Lt. Col. Lotus B. Blackwell, the battalion commander, became the first signal officer for the support group. The Page engineers, meanwhile, finished the installation of BACKPORCH in September 1962 and turned it over to the 39th Signal Battalion in early 1963. Through its pacification program the South Vietnamese government attempted to reduce the Viet Cong's influence among its citizens. Communist political cadres controlled many communities, levying taxes and drafting men into the military. In order to suppress the insurgency, the South Vietnamese had to eradicate this shadow government. Consequently, during the spring of 1962 Diem instituted the Strategic Hamlet Program through which he endeavored to relocate the rural population into fortified camps or hamlets. As part of this effort the 72d Signal Detachment, which arrived in Vietnam in October 1962, established radio communication from more than two thousand villages and hamlets to district and provincial capitals by early 1963. While the Viet Cong continued to exploit the Ho Chi Minh Trail running through Laos and Cambodia as a courier route to the north, the improved local communications helped the South Vietnamese government regain much of the countryside-or so it seemed. By the summer of 1963, with the Diem regime appearing to be winning its counterinsurgency campaign, the United States began planning a gradual withdrawal of its communications support. American optimism proved premature. The political picture suddenly darkened with the overthrow and assassination of President Diem in early November 1963, just three weeks before the assassination of President Kennedy. With the South Vietnamese military in control in Saigon, a series of rapidly changing governments followed, providing a perfect climate for the resurgence of the Viet Cong. The new American president, Lyndon B. Johnson, reaffirmed the nation's support to South Vietnam but also declared that the scheduled withdrawal would continue. At the same time, many factors converged to adversely affect signal operations in South Vietnam. The restructuring of the Signal Corps in 1964 and the resulting organizational turmoil diverted attention in Washington away from over seas operations. Chief Signal Officer David P Gibbs was preoccupied with reorganizing his own staff, while the new signal staff in the Pentagon had yet to learn the ropes. Moreover, technical difficulties developed with BACKPORCH, especially where its circuits connected with tactical equipment. Because this contingency had not been explicitly covered in the contract with Page, the 39th Signal [362] Battalion had to rely on its own resources to solve the problems. Further troubles resulted from the premature aging of the equipment in the harsh tropical environment. In addition, the absence of any redundancy built into the system left BACKPORCH extremely vulnerable to enemy action. To furnish a measure of security, the 39th Signal Battalion undertook the installation of a supplementary system, also using troposcatter, known as CROSSBOW. By the spring of 1964, however, reductions in the battalion's strength and the reassignment of its original personnel had left operations in the hands of young and inexperienced soldiers. The increasingly critical situation prompted President Johnson to announce a buildup of forces in Southeast Asia. In March 1964 the 39th Signal Battalion received more personnel, but the training available to these men had not kept up with the technology. Because all available tropo equipment had been sent overseas, none had been left behind for training purposes. Thus the reinforcements arrived in Vietnam inadequately prepared for their duties. The civilian contractors tried to train the men on site, but often lacked the time. With signal personnel rotating every year, too short a period for them to become proficient, it became necessary to retain the Page employees indefinitely. In August 1964 American and North Vietnamese forces engaged in overt combat for the first time when North Vietnamese patrol boats attacked United States Navy ships in the Gulf of Tonkin. In retaliation, President Johnson ordered air strikes against the boats and their bases in North Vietnam. Congress hurriedly passed what became known as the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, which authorized the president to take the necessary measures to repel attack against U.S. forces and to prevent further aggression in Southeast Asia.5 On the basis of this broadly worded authority, the Johnson administration justified the escalation of its involvement in Vietnam. Early in 1965 American ground troops began entering the conflict. Signal Operations in an Expanding Conflict, 1965-1967 Between the years 1963 and 1965, the role of the United States in Vietnam had shifted from the provision of advice and support to active participation in the fighting. Political instability within the South Vietnamese government, institutional corruption, and a lack of the will to fight on the part of the South Vietnamese armed forces prompted the transition. South Vietnam seemed to possess little chance for survival in the face of the Viet Cong insurgency at home and North Vietnam's increasingly active role in the conflict. By 1965, with South Vietnam obviously on the verge of collapse, the United States decided that it had little choice but to commit major military units to the war to salvage the situation. Unlike Korea several thousand miles to the north, South Vietnam lies entirely within the tropics. Geographically, it consists of three major regions: the Mekong Delta in the south, the nation's rice bowl and most populous area; the remote Central Highlands in the interior; and the Central Lowlands, a narrow coastal plain along the South China Sea. For command purposes, the South Vietnamese Army (known as the ARVN for Army of the Republic of South Vietnam) divided [363] [364] the 700-mile-long country into four corps tactical zones from north to south. To the north and west lay Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand.6 (Map 2) The United States Army's deployment started in May 1965 with the 173d Airborne Brigade. Other units soon followed, among them the 1st Cavalry Division, which reached Vietnam in September. This unit, the Army's first air mobile division, had been designed to maneuver rapidly by using aircraft, specifically helicopters. The airmobile concept adapted well to Vietnam, which lacked adequate road networks for land transport.7 The division's organic signal battalion, the 13th, possessed lighter equipment than standard divisional signal battalions and was smaller in size.8 By the end of the year, with the arrival of the 1st Infantry Division and other supporting units, the U.S. troop commitment exceeded 180,000.9 Advance elements of the 2d Signal Group arrived in South Vietnam during June 1965, and this unit became the Signal Corps' major headquarters there for the next year. The group assumed control over the 39th and 41st Signal Battalions, the latter having recently arrived.10 The 41st relieved the overextended 39th of some of its workload by taking over operations in the northern portion of South Vietnam (the I and II Corps Tactical Zones), with the 39th retaining control in the southern zones (III and IV).11 By the end of 1965 the 2d Signal Group's strength had reached nearly 6,000. Despite its substantial growth, the group had difficulty keeping pace with the Army's burgeoning communications requirements.12 The expansion of signal activities created organizational problems, since the abolition of the chief signal officer's position in 1964 had left the signal chain of command in disarray. In July 1965 General William C. Westmoreland, the U.S. commander in Vietnam, disbanded the U.S. Army Support Command, Vietnam (formerly the U.S. Army Support Group, Vietnam), and created the U.S. Army, Vietnam (USARV), to command all Army troops in South Vietnam except for the advisers. The signal officer on its staff became responsible for the Army's tactical signal operations, while long-haul communications came under the purview of the Strategic Communications Command.13 For tactical signals, the introduction of a new combat radio, the transistorized FM model AN/PRC-25, gave the soldier increased communications capability. More powerful than previous sets, it provided voice communications on 920 channels and covered longer distances (about three to five miles) across a wider span of frequencies. In fact, the ubiquitous "Prick 25" made "the greatest impact on communications of any item of equipment in the war."14 A later version, the AN/PRC-77, worked even better. The corresponding vehicular and aircraft-mounted series of FM sets, the AN/VRC-12 and AN/ARC-54, respectively, also met with success. Together, their overlapping frequencies enabled the Infantry, Armor, and Artillery to communicate with one another.15 Because the walkie-talkie proved too bulky for use in South Vietnam, the Signal Corps attempted to replace it with a new FM squad-level radio consisting of a hand-held transmitter (AN/PRT-4) and a helmet-mounted receiver [365] AN/PRC-25 RADIO (AN/PRR-9). While the new device improved communications between squad leaders and their men, it failed to achieve widespread acceptance by the troops. Squad members were issued only the receivers and could not acknowledge messages. The speaker was often too loud for patrol duty, and the earphones were uncomfortable. Eventually, soldiers stowed the sets in footlockers and forgot them. The PRC-25 proved to be the radio of choice at all echelons.16 Special Forces units operating in remote areas without the benefit of conventional signal support depended upon portable single sideband radios, such as AN/PRC-74 and AN/FRC-93.17 In response to a requirement from General Westmoreland for direct tactical links between the operations center at MACV headquarters in Saigon and all major combat units, the 69th Signal Battalion, which arrived in November 1965, established a theater-wide radioteletype net using AN/GRC-26s, machines that had proven their usefulness in Korea. The mobile command communications they provided enabled the Army to pursue the wide-ranging "search and destroy" tactics that Westmoreland advocated.18 For the first time in combat, the Signal Corps also employed an area communications system. Developed during the 1950s, this system linked the chain of command into a grid that allowed it to communicate directly with each subordinate unit. Multichannel and radio relay equipment made the intricate interconnec- [366] HELIBORNE COMMAND POST tions possible. Unit mobility improved because it was no longer necessary to string new communications wire each time a unit changed position: The unit merely connected with the nearest nodal point of the communications grid at its new location. Consequently, field wire, a staple of military signaling technology since the Civil War, saw relatively little use in South Vietnam. Overall, the area system provided more flexible communications that covered greater distances.19 Signal units received their initiation into combat during the fall of 1965, at the battle of the Ia Drang Valley in the Central Highlands near the Cambodian border. Beginning in late October, in what would become the first major ground combat between U.S. Army and North Vietnamese units, the 1st Cavalry Division engaged in fierce fighting.20 Thanks to superior mobility and firepower, American forces emerged victorious, if bloodied. Communications played a significant role in the battle, especially the use of FM airborne relay. The 13th Signal Battalion of the 1st Cavalry Division mounted radios in fixed-wing aircraft that circled at 10,000 feet and used them to retransmit voice messages between the widely dispersed combat units on the ground. This approach overcame the limitations of line-of-sight ground-based FM radio by increasing the range of PRC-25 signals from five to sixty miles and by nullifying the effects of the triple canopy jungle growth that absorbed electro- [367] magnetic transmissions. Meanwhile, brigade and battalion commanders controlled their units by using innovative heliborne command posts equipped with radio consoles. Only the absence of a significant enemy antiaircraft threat made this technique feasible.21 The combat situation in Vietnam did not conform to what Army planners in the post-Korean War period had expected to confront in the next conflict-a nuclear battlefield. According to the rationale for the pentomic and ROAD configurations, the Army had organized and equipped its units to fight in a highly mobile environment, most likely defending against a Soviet attack in Western Europe. Instead, the troops in Vietnam faced guerrilla warfare in jungles and rice paddies. Rather than maneuvering along a rapidly moving front, units mounted expeditions from fixed bases against an elusive enemy.22 Signal doctrine, likewise, had not anticipated this situation. In addition to lightweight, portable communications, the Signal Corps in South Vietnam needed to provide fixed-base communications with large antennas and heavy equipment. Divisional signal battalions had to cover operating areas of 3,000 to 5,000 square miles, compared to 200 to 300 miles in a conventional war.23 Hence signal units had to scramble for assets and divert tactical equipment to the support of base operations. Training also had to be updated, but formal instruction for fixed-station controllers did not begin at the signal schools until 1965.24 The Tonkin Gulf crisis had already highlighted weak points in the Army's strategic communications network. During this episode severe sunspot activity and occasional equipment breakdown blocked the high-frequency radio circuits between Washington and Saigon, interrupting the flow of messages traveling between the two capitals. To bolster the system's capabilities, the Army rushed an experimental satellite (SYNCOM) ground terminal to Southeast Asia. By August 1964 a satellite link to Hawaii provided one telephone and one teletype circuit and marked the first use of satellite communications in a combat zone. Improvements expanded the system's capacity to one telephone and sixteen message circuits by October 1964.25 Other technical difficulties also surfaced, especially with the BACKPORCH System. In January 1965 the network began to experience severe fading of its signals that prevented the transmission of teletype pulses, and the operators were unable to overcome the problem. Although the Page engineers shut down the terminals for maintenance-the first time BACKPORCH had been off the air-they could not correct the problem. A team of experts from the Defense Communications Agency (DCA) concluded that the phenomenon resulted from a temperature inversion, which occurs when the upper layers of the atmosphere are uncharacteristically warmer than the lower layers.26 Already concerned about the vulnerability of his communications, General Westmoreland also worried that the Viet Cong would begin targeting signal sites. The complex at Phu Lam, a suburb of Saigon, then housed the only Defense Communications System message relay facility in the country. (It had replaced the STARCOM station in Saigon.) This communications gateway to Vietnam handled [368] AERIAL VIEW OF THE COMMUNICATIONS COMPLEX AT PHU LAM 250,000 messages per month by early 1965, and a backlog was beginning to develop.27 Plans were drawn, therefore, to create a base theater network with a diversity of routing and transmission methods that would bring modern communications to the battlefield. Known as the Integrated Wideband Communications System (IWCS), it was to combine coastal undersea cables with automatic telephone, teletype, and data systems. Incorporating the BACKPORCH and WETWASH facilities, the IWCS would become part of the global Defense Communications System.28 The installation of this fixed network would also free the units' mobile equipment for tactical purposes. Once again, Page Communications Engineers received the construction contract for the Vietnam portion of the system, while Philco-Ford built the terminals in Thailand. Meanwhile, the completion of the WETWASH project in December 1964 made high-quality overseas circuits available between the United States and South Vietnam.29 A shortage of personnel to operate troposcatter terminals posed an additional dilemma. The signal schools could not initially produce qualified graduates fast enough. Since few records had been kept of previously trained soldiers, the Army had little way to locate experienced operators still on active duty. Moreover, regulations prohibited the involuntary reassignment of military personnel overseas for two years, a period later reduced to nine months for those with certain critical skills. As a result, the Department of Defense offered increased pay and reenlistment bonuses to recruit and retain soldiers with such skills, many of them in the field of communications-electronics and liable to be lured away by private industry. Westmoreland also worried whether the civilian contractors could be counted on as hostilities intensified, but in this case his concerns proved unjustified.30 [369] Despite their dependence on high technology, Army communicators also operated some less-than-modern equipment, such as World War II-vintage teletypewriters and switchboards. Problems developed, however, when these antiquated machines had to interface with modern digital devices. The older equipment was also more susceptible to dust and overheating.31 Occasionally, communicators reached even further into the past: In the 1st Cavalry Division, pigeons experienced a brief revival, but the experiment proved unsuccessful. When radios went out or were otherwise unavailable, soldiers used colored smoke signals to direct artillery or to call for air strikes and medical evacuation. At night, they used flares, flashlights, and light panels.32 Although messengers sometimes carried information, they faced the constant threat of ambush. In contrast, the insurgents made extensive use of couriers, since they were able to blend into the general populace much more readily than Americans. The proliferation of radios, while providing more mobile and flexible communications, nonetheless also created serious problems. Because the electromagnetic spectrum contained too few frequencies to carry the existing traffic, frequency management became a necessity to control the crowded airwaves. In 1965 a division had fifteen frequencies dedicated to the use of each of its brigades. By mid-1967, only seven were available for all three brigades. The remainder of its 200 allotted frequencies had to be shared with other units. Furthermore, the extension of signals beyond their assigned area by means of airborne relay caused them to interfere with radio nets in other areas, including those of the enemy, who was using the same frequencies. Although a solution was reached through the assignment of certain frequencies for the sole use of airborne relay sets, this procedure limited the number of frequencies generally available.33 Communications security presented another major concern. The enemy conducted highly successful surveillance of U.S. radio nets, and American units made interception easier by practicing poor radio discipline, such as transmitting large numbers of messages in the clear and neglecting to change call signs periodically. Thus the enemy received advance warning of many U.S. air strikes and gathered other types of intelligence. The situation improved after mid-1967 when the Defense Communications Agency began installing the Automatic Secure Voice Communications (AUTOSEVOCOM) System at major headquarters and command posts. The system scrambled voice impulses prior to transmission.34 In the field, standard security measures, such as the manual encryption and decryption of messages, made communications slower and more complicated, a distinct disadvantage in the heat of battle. To make things easier, voice security equipment for stationary and vehicular radios, known as KY-8, began reaching tactical units in 1965. Unfortunately, this device not only reduced transmission range but also generated a great deal of heat.35 Security equipment for aircraft radios, designated KY-28, and for manpack or mobile use, KY-38, became available in 1967. The latter, in combination with the PRC-77 radio, weighed fifty pounds, a significant burden for the foot soldier. The reliance on voice [370] radio also resulted in an erosion of the operators' ability to communicate in Morse code, a skill that could become necessary when jamming or other forms of interference occurred.36 Power generation also posed a problem. Since South Vietnam lacked sufficient supplies of commercially generated electricity, the Army had to supply the power needed to run electrical machinery even at its fixed bases.37 Communications equipment thus received power either from fixed-plant generators, portable generators, or batteries. Exposed to the elements, batteries soon perished. The development of magnesium batteries helped, for they lasted longer than the zinc and carbon oxide variety and did not need to be kept cool. Fortunately, the enemy rarely exploited the vulnerability of the generators.38 Because Signal Corps doctrine had anticipated dependence upon radio relay for long-distance communications on a fluid battlefield, the Corps in 1961 had ceased training its personnel in cable installation and splicing. In fact, the Department of Defense had assigned training in cable splicing to the Air Force, and the Army depended upon contractors for most of this work. When the Signal Corps unexpectedly found itself tasked with upgrading the telephone system throughout South Vietnam, it had only one cable construction battalion, the 40th Signal Battalion, on its rolls. Beginning in the fall of 1966, this unit installed several million feet of cable throughout the theater. The work performed by the men of the 40th enabled the Signal Corps to provide dial telephone service for the first time throughout a combat zone. By 1969 automatic dial exchanges had been installed, giving South Vietnam access to the worldwide Automatic Voice Network (AUTOVON), the principal long-haul voice communications network within the Defense Communications System.39 By early 1966 Westmoreland had created the I and II Field Forces as corps-size headquarters to oversee operations in the II and III Corps Tactical Zones, respectively, the areas of heaviest fighting. Each field force had a signal officer and an assigned signal battalion.40 To improve command and control of signal operations, the Army created the 1st Signal Brigade during the spring of 1966. The brigade consolidated signal units above field force level into one command and merged tactical and strategic communications within the combat zone. The 1st Signal Brigade was activated on 1 April 1966 with its headquarters initially at Saigon and later at Long Binh. Brig. Gen. Robert D. Terry became the brigade's first commander. In this position, Terry served two functions, operating not only in his normal role, but also as the staff signal officer (J-6) for USARV The new command, the first TOE brigade in the Signal Corps' history, comprised all signal units in Vietnam except those organic to tactical units.41 The new arrangement limited the 2d Signal Group, now subordinate to the brigade, to operations in the III and IV Corps zones. The 21st Signal Group took charge of communications in the I and II Corps zones.42 In May 1967 the 160th Signal Group joined these units to provide headquarters support in the Saigon and Long Binh areas, duties previously performed by the 2d Signal Group.43 The 1st Signal Brigade also included the 29th Signal Group in Thailand.44 [371]

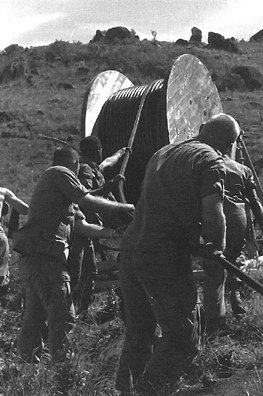

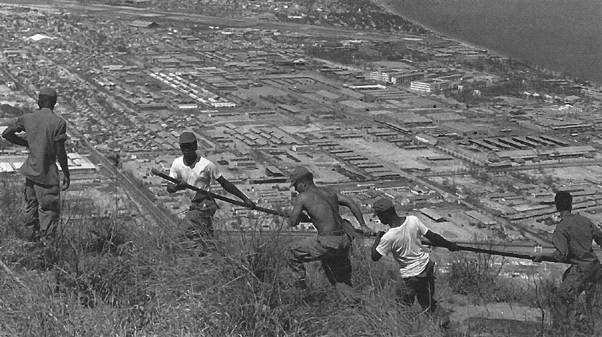

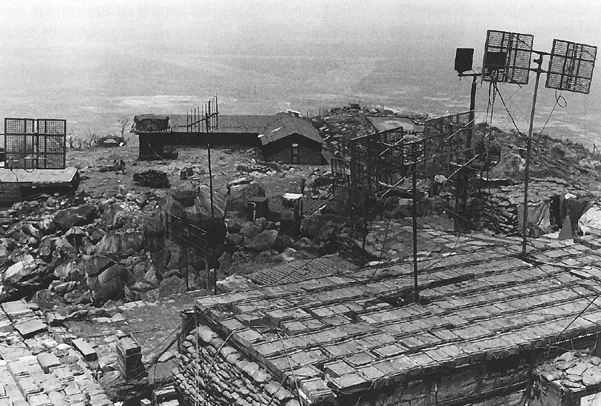

[372] During 1966 the war continued to escalate as the United States increased its bombing of North Vietnam, and American troops continued to pour into South Vietnam. By mid-year U.S. forces were shouldering the burden of combat, relegating the South Vietnamese to a largely subordinate, defensive role. Throughout the next two years, as U.S. forces took the offensive to the most remote corners of the country, communications became the backbone of the Army's tactical doctrine combining mobility and firepower. In the midst of the intensifying conflict, the Signal Corps had not forgotten its pictorial mission. Division-level signal battalions continued to have organic audiovisual capabilities, and brigade-and field force-level signal battalions also contained photographic sections. The 160th Signal Group received responsibility for countrywide photographic support, providing backup services for the signal battalions. The Southeast Asia Photographic Center at Long Binh, operated by the 221st Signal Company, became the most extensive photographic facility ever operated in a combat zone, capable of color processing and printing.45 In addition, recently organized special photographic detachments provided quick-reaction documentation of the Army's activities, not only in South Vietnam but around the world. This footage was used for staff briefings and other Army information purposes.46 Meanwhile, the Military Affiliate Radio System (MARS) carried on the Signal Corps' long-standing relationship with amateur radio operators. In addition to its primary purpose of providing a backup for Department of Defense communications, the MARS network in South Vietnam connected servicemen with their families back home. When a soldier wanted to call home, a MARS operator would call a "ham" in the United States who would in turn dial the soldier's family on the telephone and then patch the radio transmission into the telephone system.47 After overcoming a series of bureaucratic delays and other obstacles, the first links in the Integrated Wideband Communications System became operational by the end of 1966.48 The 1st Signal Brigade, in conjunction with the Defense Communications Agency, managed the installation of the network, a mammoth job. Site construction alone posed a host of difficulties. Some hilltop locations were so remote that men and equipment had to be brought in by helicopter. In many cases the communicators shared the hills with the enemy, who occupied the slopes. In Thailand, elephants had been used to carry equipment up the mountains, but they had refused to climb above 6,000 feet. Bad weather, combat, and other unanticipated problems also retarded progress. The entire IWCS, comprising sixty-seven links in South Vietnam and thirty-three in Thailand, finally reached completion early in 1969. The system, which totaled 470,000 circuit miles, allowed American commanders to control U.S. air power throughout Southeast Asia, to manage widely separated logistical and administrative bases, and to link major commands throughout South Vietnam. It cost more than $300 million to build.49 The completion of the IWCS, with its high-quality circuits, enabled the introduction of digital communications to the combat zone. By mid-1968 South Vietnam had become part of the Automatic Digital Network (AUTODIN), a [373] TECHNICIAN FROM PAGE COMMUNICATIONS worldwide all-electronic, computer-controlled traffic directing and routing system. Digital communications replaced the old teletype torn-tape relays and the manual punch cards, which had been both cumbersome and slow. The Army used computers for administrative and logistical communications, and AUTODIN helped reduce the backlog that had developed. The sensitive equipment, however, had to be kept at a constant 73 degrees Fahrenheit and 54 percent humidity, and operators had to wear special shoes to retard dust and dirt.50 Satellite communications, meanwhile, proved disappointing. In 1967 the Defense Communications Satellite System began to replace the SYNCOM links, originally designed only for research and experimentation. Using satellites in nonsynchronous orbits, the fourteen ground stations (two of them in South Vietnam) communicated through twenty-seven satellites, using whatever satellites were mutually visible as relays. Due to the poor quality of the signals, the system handled only voice, teletype, and low-speed data transmissions instead of the digital and secure voice circuits for which it had been intended. The Defense Communications Agency also leased channels from the commercial Communications Satellite Corporations.51 Back on the ground, the vagaries of combat continued to provide challenges for communications. During Operation CEDAR FALLS, launched on 8 January 1967, General Westmoreland sought to destroy an enemy stronghold known as the Iron Triangle that threatened Saigon. Few enemy soldiers were captured, but the attackers discovered extensive tunnel complexes that served as headquarters and storage depots. During the operation the "tunnel rats"-soldiers who ventured underground to ferret out the enemy-found communications to be a major difficulty. Although they carried hand telephones or microphones strapped to their heads ("skull mikes"), the devices often became inoperable after a short period, as mouthpieces became clogged with dirt or cracked from constant jarring. At least the communications wire trailed by these brave men often aided their rescue or withdrawal through the dark labyrinths.52 [374] Riverine operations in the Mekong Delta presented yet another set of problems, as the 9th Signal Battalion of the 9th Infantry Division discovered. Here swamps and heavy jungle made ground combat virtually impossible, and the Viet Cong controlled the few roads in the region. Hence tactical units conducted operations afloat. In this heavily populated region, unoccupied solid ground for signal sites was a scarce commodity. Moreover, the moist soil made a poor electrical ground. To remedy this situation, the battalion buried scrap metal deep below the water table and welded it to large rods that served as grounding points. The battalion also tried to use captive gas-filled balloons to elevate radio transmitters. Although this method greatly extended the transmission range of the sets, heavy monsoon winds rendered the experiment a failure. While supporting the Mobile Riverine Force, a joint Army-Navy endeavor, the 9th Signal Battalion additionally faced the challenges posed by communicating from shipboard. While in motion, operators had to constantly rotate their directional antennas to maintain a strong signal with divisional headquarters on land. When the boats anchored, field wire strung between the vessels carried telephone communications.53 By the end of 1967 the United States had committed nearly five hundred thousand troops to South Vietnam. The Army, contributing about two-thirds of the total, had sent seven divisions and two separate brigades.54 Besides the signal units organic to these combat forces, the 1st Signal Brigade, now commanded by Brig. Gen. William M. Van Harlingen, Jr., comprised twenty-one battalions organized into five groups. Its strength totaled about twenty thousand men who occupied over two hundred signal sites throughout South Vietnam.55 In addition to American forces, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, and Thailand all contributed units, as of course did South Vietnam, bringing the total manpower engaged to well over a million. Unlike the situation during the Korean War, however, the American commander had no command authority over the South Vietnamese or other friendly troops. As the war progressed, the sophisticated level of communications available to the allies proved both a blessing and a curse. Rapidly changing technology caused training to lag behind operations. Despite triple shifts of classes running around the clock, both the Signal Center and School at Fort Monmouth (which had overall doctrinal responsibility for the Signal Corps) and the Southeastern Signal Corps School at Fort Gordon (where most enlisted Signal Corpsmen received their training) had trouble keeping up with their burgeoning student populations. Much of the new equipment was so expensive and in such limited supply that the signal schools had difficulty obtaining prototypes for instructional purposes. Thus, much on-the-job training occurred. To provide the requisite instruction, new equipment training teams from the Electronics Command at Fort Monmouth, successors to the new equipment introductory teams of World War II, accompanied hardware into the field. In the case of commercially designed equipment, the manufacturers sent their own representatives. By the time the operators became proficient, however, their year of duty had come to an end, and the learning process began all over again. The establishment of the [375] Southeast Asia Signal School at Long Binh by the 1st Signal Brigade in 1968 helped somewhat to alleviate the training dilemma.56 Despite these myriad problems, the Vietnam conflict marked a milestone in military signaling. For the first time, high-quality commercial communications became available to the soldier in the field. But there were trade-offs. Although providing the commander with a greater range of command and control, they also limited his freedom of action. The traditional distinction between tactical and strategic communications became blurred when the president and the Joint Chiefs of Staff could use strategic links to direct operations from Washington. As early as 1965 President Johnson had spoken directly to a Marine regimental commander under fire outside Da Nang. Such technical wizardry did not automatically confer upon the users, however, the wisdom about how best to apply the new technology.57 The Tet Offensive and the Quest for Peace The year 1968 proved a crucial one for the future direction of the war. Beginning on 29-30 January, during the celebration of the Vietnamese lunar new year, known as Tet, traditionally a cease-fire period, the North Vietnamese and the Viet Cong launched a general offensive throughout South Vietnam.58 They hoped to generate a popular uprising against the government and to inflict a military disaster upon the United States similar to that experienced fourteen years earlier by the French at Dien Bien Phu. Although the American high command had received intelligence indicating that the enemy planned a major offensive, Westmoreland and his staff had not anticipated the scale of the attack.59 During the course of the Tet offensive, many signal sites came under attack, including ten in the wideband system. From 31 January to 18 February, the period of heaviest fighting, signal troops suffered hundreds of casualties. In the defense of their positions, signalmen proved once again that they could both communicate and shoot. Damage to signal equipment and facilities totaled several million dollars, with exposed cables particularly hard hit. Although communications experienced few serious disruptions, signal support became tenuous as battle fatigue and dwindling supplies took their toll. By the end of February, with most of the 1st Signal Brigade's organic aircraft no longer in good enough condition to ferry repairmen and equipment between sites, only an air courier service established with the assistance of the Air Force kept communications from breaking down.60 The northern city of Hue, once the imperial capital of the Nguyen dynasty, became the scene of the most prolonged and bloody engagement of the offensive. Viet Cong and North Vietnamese forces seized and held the city for three weeks before American and South Vietnamese troops regained control. During the initial hours of the battle the U.S. advisers' compound and the 37th Signal Battalion's tropospheric scatter site were the only positions within the confines of the city to remain under American control. At this important signal position, [376] which provided the main link with the Marine base at Khe Sanh, forty-one signalmen repelled repeated assaults and even captured the commander of the attacking unit. After thirty-six hours of fighting, two companies of marines relieved the beleaguered communicators.61 During the occupation the Communists slaughtered thousands of Hue's residents and much of the beautiful historic city was destroyed in the fighting. American and South Vietnamese forces finally recaptured the city on 25 February. Located on the outskirts of Saigon, Tan Son Nhut Air Base, which housed both MACV headquarters and the South Vietnamese military, came under attack from three directions during the night of 31 January. With the opening barrage, the 69th Signal Battalion moved quickly to defend its signal facilities in the vicinity. The battalion provided communications not only to MACV headquarters but also to various military and civilian agencies in the Saigon area. In addition to its signal positions, the battalion was responsible for manning a sector of the air base's outer perimeter. During the first hour of fighting two of its members were killed while defending a main gate. Elements of the 69th also helped rescue Americans trapped by the attack throughout the city.62 While causing considerable disruption within South Vietnam, the Tet offensive failed to achieve the decisive military and political victories the Communists had anticipated. Back in the United States, however, the enemy offensive accelerated disillusionment with the Southeast Asian conflict. Although U.S. and South Vietnamese forces had inflicted severe casualties upon the Viet Cong and defeated them on the ground, dramatic television footage of burning cities and fleeing refugees demonstrated to many Americans that the war was not going as well as their government and military officials had proclaimed.63 A "credibility gap" began to grow, along with political pressure for the Johnson administration to bring the conflict to a speedy conclusion. The Marines' protracted battle for Khe Sanh, beginning in early February, further eroded popular support for the war. It appeared initially that the surrounded garrison in the mountains near the South Vietnam-Laos border faced annihilation. The enemy may have planned to seize this isolated post and use it to claim control of South Vietnam's two northernmost provinces. Westmoreland, who wanted to hold the position as a base for a possible drive into Laos, even considered the employment of tactical nuclear weapons.64 Meanwhile, the troposcatter system between Khe Sanh and Hue, operated by the 544th Signal Detachment, remained the base's primary link to the outside world. President Johnson, understandably concerned about the outcome of the battle, arranged for reports to be sent directly to the White House via the troposcatter network. On 2 February this link was disrupted when an enemy rocket struck the signal team's bunker, killing the officer in charge and three radio operators. Assisted by two Marine communicators, the team's lone survivor, Sp4c. William Hawkinson, reestablished communications and held out for three days until help arrived. Although the 1st Cavalry Division succeeded in relieving Khe Sanh by early April, some critics compared the costly defense to the French debacle at Dien Bien Phu. Despite the sacrifices [377] made to hold Khe Sanh, the United States decided to abandon the base less than three months later.65 Other events around the world exacerbated the public's sense of crisis. Immediately prior to Tet, the North Koreans had seized the intelligence ship USS Pueblo on 23 January 1968, an ominous occurrence with ambiguous connections to developments in Vietnam. Fortunately, after extended negotiations the North Koreans released the captain and crew. Of more direct import was the visit in late February of the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Earle G. Wheeler, to the war zone to assess the impact of the Tet offensive. He returned to Washington with a gloomy report that included a request for an additional 200,000 American troops. To achieve this goal, however, the president would have to mobilize the National Guard and other reserve forces.66 In setting his policy toward Vietnam, President Johnson had refrained from asking Congress to declare war for fear that the Soviet Union and China would intervene. He had also declined to call up the reserves, relying instead upon the draft to provide the necessary personnel. Johnson had hoped to conduct a limited war in Southeast Asia that would not jeopardize his "Great Society" domestic programs. Nonetheless, he had sought to pursue a course that would eventually achieve a military victory. In the wake of the Tet offensive, the president was forced to reassess his Vietnam strategy. Although he had authorized an additional 10,500 combat troops immediately after Tet, the president faced strong political opposition to any further major troop buildup. Furthermore, Hanoi had indicated a possible interest in peace talks. For several weeks during February and March the president weighed the various options for the future course of the war presented to him by his senior advisers.67 With political support for the war crumbling and his health deteriorating, President Johnson surprised the nation by announcing on 31 March 1968 that he would not run for reelection. He also took this opportunity to make public his decisions about the war. There would be no massive infusion of forces. Rather, in an effort to deescalate the conflict and move toward peace, Johnson informed the nation that he had ordered a halt to the bombing of North Vietnam except just above the DMZ. The government's bombing policy had proved increasingly unpopular and, as the Tet offensive clearly demonstrated, had not prevented North Vietnam from moving sufficient forces into South Vietnam to launch a general offensive. Johnson further indicated that the South Vietnamese would henceforth shoulder a greater share of the combat.68 With the announcement of the bombing halt, the North Vietnamese agreed to begin peace talks. Despite expectations of initial progress, these negotiations, like those during the Korean War, proved to be long and frustrating. For many months the negotiators in Paris could not even agree on the shape of the conference table. The president's continuing delay in mobilizing the reserves had already adversely affected the Signal Corps by preventing it from drawing upon the trained personnel working in the communications industry upon whom it had relied so heavily in both world wars and Korea. In addition to providing the Army [378] SIGNAL SITE ON BLACK VIRGIN MOUNTAIN. AERIAL VIEW; BELOW, ANTENNAS

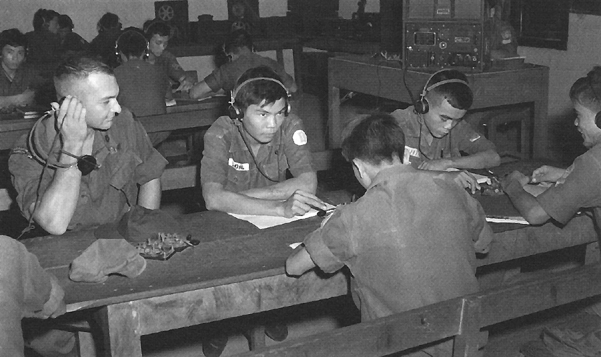

[379] with skilled personnel, the signal schools had hoped to use reservists to augment their teaching staffs.69 A call-up would also have restored the strategic reserve, those forces that remained in the continental United States available for deployment. The resources of the Signal Corps' strategic reserve, the 11th Signal Group at Fort Huachuca, had been seriously depleted to bolster the communications buildup in Southeast Asia. Finally, after the Tet offensive, President Johnson authorized a limited call-up of the reserves in the spring of 1968 to provide support troops for the war effort. As a result, the 107th Signal Company of the Rhode Island Army National Guard soon found itself in South Vietnam assisting the 1st Signal Brigade.70 Although the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese generally avoided large-scale offensive operations following Tet, attacks on signal installations increased. One of the worst occurred on 13 May 1968 atop Nui Ba Den, or Black Virgin Mountain, a remote site near Tay Ninh. During the night the Viet Cong killed twenty-three communicators and destroyed most of their equipment. Pfc. Thomas M. Torma of the 86th Signal Battalion won a Silver Star for his heroism while defending the site. In August the enemy again attacked this position and once more put it off the air temporarily. By the summer of 1968 enemy attacks on signal positions numbered eighty per month.71 In July 1968 General Westmoreland left Vietnam for a new assignment in Washington as Army chief of staff. His successor, General Creighton W Abrams, Jr., had previously served as Westmoreland's deputy. For the next four years General Abrams presided over America's changing role in Vietnam in the wake of the Tet offensive.72 As for the ongoing signal effort, the 1st Signal Brigade reached its peak strength of 23,000 late in 1968. At that time it comprised six signal groups containing twenty-two signal battalions.73 Signal Operations in a Contracting Conflict, 1969-1975 With the inauguration of Richard M. Nixon in January 1969, the nation's war policy changed dramatically. Nixon had narrowly defeated Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey in a tumultuous campaign for the presidency in which Vietnam had been the chief political issue. Nixon had pledged to end the war, and he announced plans to begin a gradual disengagement of American forces early in his administration. The number of American servicemen in Vietnam peaked at 543,000 during the spring of 1969.74 In July the United States began phased troop withdrawals. While the American ground combat role steadily declined, U.S. air support remained significant. As the United States curtailed its involvement, the war entered a new stage, known as Vietnamization. According to this policy, first proposed by President Johnson in his March 1968 speech, the burden of combat gradually shifted to the South Vietnamese. This process, in conjunction with pacification, would, it was believed, make the South Vietnamese self-reliant and able to carry on the war alone. To achieve this objective, the United States undertook an intensive pro- [380] VIETNAMIZATION - AMERICAN SOLDIER LISTENS IN TO A CLASS IN RADIO CODE AT THE gram to improve the training and to modernize the equipment of the ARVN in preparation for its assumption of expanded responsibilities. Within the 1st Signal Brigade, Vietnamization had been under way for some time through the "Buddies Together" (Cung Than Thien) program, which matched American signal units with their South Vietnamese counterparts. They trained together, celebrated each other's holidays, and jointly participated in civic action projects. Brig. Gen. Thomas M. Rienzi, who became brigade commander in February 1969, strongly supported the program and was a popular visitor to South Vietnamese signal units.75 The 39th Signal Battalion, for example, sponsored the South Vietnamese signal school at Vung Tau. Signal units also built schools, dug wells, entertained orphaned children, and distributed food and clothing to local hamlets. By the end of 1969 twenty-five brigade units were actively participating in the program.76 Through the Buddies program the 1st Signal Brigade helped prepare the South Vietnamese signal corps to eventually run the fixed-communications system. The Vietnamese communicators were already capable of operating and maintaining tactical communications equipment, but they lacked the skills to handle the more complex strategic facilities. Signalmen received instruction from American technicians at Vung Tau as well as on-the-job training at signal sites throughout the country. As the pace of U.S. troop withdrawal increased, civilian contractors assumed the training mission from the brigade and operated and maintained the sites scheduled for transfer until the South Vietnamese were ready to take them over.77 [381] As the United States disengaged from Vietnam and sought a negotiated settlement of the conflict, the fighting continued, especially around Saigon and in the northern provinces. The Communists launched another Tet offensive in 1969, but the attacks were much weaker than the year before. Still, hundreds of American casualties resulted. Although the intensity of the war generally abated, fierce battles remained to be fought, such as that for Hamburger Hill in May 1969. During this battle the din became so loud that it was impossible to use radios.78 During the spring of 1970 President Nixon authorized a limited invasion of Cambodia, long used as a sanctuary and logistical base by the North Vietnamese. The U.S. government had not previously allowed its ground forces to operate out side the borders of South Vietnam. By destroying the enemy's bases in Cambodia, the United States hoped to buy time for Vietnamization and to assist the new pro-Western regime of General Lon Nol. The attack on Cambodia, made on short notice, provided yet another test for Army communicators. The 13th Signal Battalion found that its lightweight equipment served well, allowing the men to move out quickly and provide reliable communications throughout the campaign. The 125th Signal Battalion, however, more dependent upon fixed equipment, could not adapt as quickly. The 1st Signal Brigade, meanwhile, activated circuits in its area network to keep the top commanders in South Vietnam in touch with their force commanders in Cambodia. It also provided units in Cambodia with access to the Defense Communications System, and messages transmitted from field command posts in Cambodia went directly to the White House.79 At home, critics viewed the invasion of Cambodia (euphemistically referred to by the administration as an "incursion") as a widening of the war, and vehement protests rapidly spread across the nation, especially on college campuses. On 4 May one such demonstration resulted in tragedy when Ohio National Guard troops opened fire on students at Kent State University and killed four people. By the end of June the United States had pulled its troops out of Cambodia after having achieved only mixed results.80 About one year later, when South Vietnamese troops conducted a similar excursion into Laos, LAM SON 719, no Americans accompanied them and the results were even more questionable. Although the war on the ground had reached a stalemate by the latter half of 1971, the air war over Laos and North Vietnam continued. Throughout that year the North Vietnamese, with Russian support, prepared for a major campaign. The blow came on 30 March 1972 when North Vietnam launched an invasion of the South, known as the Easter offensive. With most U.S. combat forces now gone, the burden of the fighting fell to the South Vietnamese, and it initially appeared that they would be overwhelmed. President Nixon responded by ordering a resumption of sustained bombing in the North as well as the mining of Haiphong Harbor, North Vietnam's largest port. By September Saigon's forces, backed by American air and naval firepower, had broken the offensive. Although failing to bring about the collapse of South Vietnam, the 1972 invasion left the Communists in control of more territory and in a stronger bargaining position than before.81 [382] In the aftermath, the stalled peace talks resumed in Paris, and National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger, who led the American negotiating team, declared that "peace is at hand." While his optimism proved premature, the fitful negotiations finally resulted in the signing of a cease-fire agreement in January 1973. According to its terms the United States would terminate all direct military support to South Vietnam while North Vietnam agreed to end its infiltration of the South. North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces would, however, be allowed to remain in South Vietnam. The agreement also promised national reconciliation at some future date. Although North Vietnam released its American prisoners of war, thousands of men remained listed as missing in action.82 As the war wound down, the 1st Signal Brigade steadily decreased in size. By 1972 its strength stood at less than twenty-five hundred men. On 7 November 1972 the brigade headquarters left Vietnam and transferred its colors to Korea.83 The 39th Signal Battalion, the first signal unit to arrive in Vietnam, became the last to leave. As its final wartime mission, the battalion supported the international peacekeeping force that monitored the troop withdrawal and prisoner exchange. The unit departed Vietnam on 15 March 1973, almost eleven years to the day after its first elements had arrived. During its long stint the 39th had participated in all seventeen campaigns and earned five Meritorious Unit Commendations.84 By the summer of 1973 the United States had completed the withdrawal of its combat troops.85 North Vietnam immediately began violating the cease-fire by moving large numbers of troops into South Vietnam. Although President Nixon had pledged to President Nguyen Van Thieu of South Vietnam that the United States would enforce the Paris agreement, the Nixon administration, increasingly preoccupied with the Watergate scandal, failed to honor its commitment. Moreover, Congress sharply reduced military aid to South Vietnam and in November 1973 passed the War Powers Resolution that prohibited the reintroduction of American combat forces without its consent. The cutoff of funds also left the South Vietnamese unable to maintain the communications network the Americans had left behind. While the war-weary United States focused its attention on its domestic difficulties, which culminated in the resignation of the president in August 1974, the situation in Southeast Asia steadily deteriorated. On 29 April 1975 Saigon fell to the Communists. Among the thousands of Americans hastily evacuated before the final collapse were the remaining civilian communications technicians who had stayed behind to assist the South Vietnamese.86 The undeclared war in Vietnam presented a study in contrasts. While the United States conducted high-technology warfare, its opponents generally employed only the most primitive of means. Instead of the mobility offered by motor vehicles and aircraft, the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese forces traveled primarily on foot. They most often attacked at night. Lightly armed and equipped, [383] they inflicted many casualties by ambush, mines, and booby traps, seldom engaging in set-piece battles. The United States Army, meanwhile, employed the devastating firepower of modern weapons, but lacked the ability to bring the North Vietnamese to battle, except on occasions of their own choosing. The communications available to the two sides reflected this disparity. Into a primitive society, where electronic media had been virtually unknown, the United States Army introduced the most sophisticated signaling systems ever seen on the battlefield-the products of a century of development of military communications. American soldiers used such advanced methods as satellites, tropospheric scatter, and FM radio, items not available to the enemy. While the Communist forces communicated with telephones and AM radios supplied by their allies, particularly Russia and China, as well as with captured American equipment, such items remained in short supply and were used sparingly. Consequently, the North Vietnamese continued to rely upon couriers and such simple devices as whistles, bugles, and visual signals. Nevertheless, the overwhelming technological superiority of the U.S. Army could not provide solutions for what were basically political questions at the heart of the conflict.87 While considerable rancor and bitterness remain associated with the Vietnam defeat, there is little argument that the U.S. Army's communications worked well-the Signal Corps got the message through. In performing their mission, Army communicators sustained relatively heavy casualties, especially among radiotelephone operators accompanying combat operations. Their vital mission coupled with their high visibility, the telltale antennas protruding from the radio sets, made them prime targets.88 Efficient communications helped reduce battle fatalities, however, by speeding up medical evacuation procedures.89 The list of signal soldiers decorated for gallantry in Vietnam includes Capt. Joseph Maxwell ("Max") Cleland, who received the Silver Star. In April 1968 Cleland, serving as the communications officer with an infantry battalion, sustained grievous injuries in a grenade explosion near Khe Sanh. After undergoing extensive hospitalization, he entered politics. Under President Jimmy Carter, Cleland became the director of the Veterans Administration, the first Vietnam veteran to hold that office. He subsequently served several terms as secretary of state of his native state of Georgia.90 While no members of the Signal Corps received the Medal of Honor in Vietnam, several soldiers serving as communicators earned this recognition. One of them, Capt. Euripides Rubio, Jr., communications officer for the 1st Battalion, 28th Infantry, posthumously won the award for his gallantry during Operation ATTLEBORO in Tay Ninh Province in November 1966. During an attack on 8 November, Rubio left the relative safety of his position to help distribute ammunition and aid the wounded. When the commander of a rifle company had to be evacuated, Rubio, already wounded himself, took over. Continuing to risk his life to protect his troops, he was eventually felled by hostile gunfire after tossing a misdirected smoke grenade into enemy lines. Because of Rubio's heroism, the air strike thus called for fell upon the enemy's position rather than on his own men.91 [384] In addition to the end of the fighting in Vietnam, America's foreign policy underwent other transformations during the early 1970s. In 1972 Nixon had become the first American president to visit the People's Republic of China. The United States also initiated a policy of detente toward the Soviet Union, including the signing of arms control agreements, that signaled a thawing of the Cold War. The changing relationship between East and West held profound implications for world affairs during the last quarter of the twentieth century and for America's role therein.92

[385] Return to Table of Contents

|

|||||||||||