The U.S. Army and the Lewis & Clark

Expedition

Part 5: Camp River Dubois and the Missouri River Trek

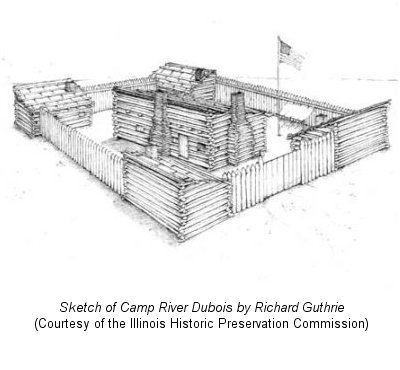

Upon arriving at St. Louis, Lewis left the party to handle logistical

arrangements and to gather intelligence on Upper Louisiana. Clark took

the party upriver about eighteen miles to the mouth of the Wood River,

a small stream that flowed into the Mississippi River directly across

from the mouth of the Missouri River. Here, Clark constructed Camp River

Dubois, which was finished by Christmas Eve 1803.

Once the camp was established, Clark set about preparing for the arduous

journey ahead. Throughout the winter months he selected and trained

personnel, modified and armed the keelboat and pirogues, and assembled

and packed supplies. For all his efforts, William Clark never received

the captaincy Lewis had promised him. Instead, the War Department commissioned

Clark a Lieutenant of Artillery. Nevertheless, Lewis called Clark Captain

and recognized him as co-commander, and the men of the expedition never

knew differently.

On 31 March 1804, Lewis and Clark held a ceremony to enlist the men

they had selected as members of “the Detachment destined for the

Expedition through the interior of the Continent of North America.”

In addition to the eleven men previously selected, Lewis and Clark chose:

Sgt. John Ordway, Cpl. Richard Warfington, and Pvts. Patrick Gass, John

Boley, John Collins, John Dame, Robert Frazer, Silas Goodrich, Hugh

Hall, Thomas Howard, Hugh McNeal, John Potts, Moses Reed, John Robertson,

John Thompson, Ebenezer Tuttle, Peter Weiser, William Werner, Issac

White, Alexander Willard, and Richard Windsor. In their Detachment Order

of 1 April 1804, Captains Lewis and Clark divided the men into three

squads led by Sergeants Pryor, Floyd, and Ordway. Another group of five

soldiers led by Corporal Warfington would accompany the expedition to

its winter quarters and then return to St. Louis in 1805 with communiqués

and specimens collected thus far.

With their military organization established, Lewis and Clark began

final preparations at Camp River Dubois and in St. Louis for

their trek up the Missouri River. Clark molded the men into a team

through a regimen of drill and marksmanship training, while Lewis was

busy in St. Louis arranging logistical support for the camp and obtaining

intelligence on the expedition’s route and conditions along the

way. Discipline was tough, and Clark made sure that the men were constantly

alert, that they knew their tasks on both river and land, that their

camps were neat and orderly, and that they cared for their weapons and

equipment. He dealt firmly with any form of insubordination or misbehavior.

At the same time he rewarded the winners of marksmanship contests and

those who distinguished themselves on their work details. Clark’s

fine leadership proved effective, as the expedition recorded only five

infractions during its two-and-a-half-year trek, a record unmatched

by any other Army unit of the time.

On the afternoon of Monday, 14 May 1804, Clark and his party left Camp

River Dubois, crossed the Mississippi River, and headed up the Missouri.

The Expedition proceeded slowly toward St. Charles, because Clark wanted

to insure the boats were loaded properly for the journey. Two days later

they reached St. Charles, made adjustments to the loading plan, and

awaited Lewis. At St. Charles, Clark also enlisted two additional boatmen:

Pvts. Pierre Cruzatte and Francois Labiche. Both knew the tribes of

the Missouri River Valley and would serve as interpreters. On 20 May,

Lewis arrived from St. Louis with a group of prominent St. Louis citizens

who wanted to see the expedition launched. The next afternoon, a crowd

lining the riverbank bade farewell to Captains Lewis and Clark and their

expedition.

“The Commanding Officers” jointly issued their Detachment

Orders for the Expedition on 26 May. This decree established a routine

while making it clear to the men that this was a military expedition

into potentially hostile territory. Lewis and Clark refined the organization

previously agreed upon at Camp River Dubois. The three original squads

were redesignated “messes” and manned the keelboat, while

Corporal Warfington’s detachment formed a fourth mess and rode

in the “white” pirogue. The civilian boatmen formed the fifth

mess and rode in the “red” pirogue. Because he was the better

boatman, Clark usually stayed on the keelboat while Lewis walked on

shore and made his scientific observations. Occasionally, they would

rotate and Lewis would catalog specimens on the keelboat.

Captains Lewis and Clark now commanded through the three sergeants,

who rotated duties on the keelboat. One always manned the helm, another

supervised the crew at amidships, and the third kept lookout at the

bow. The senior sergeant was Ordway, who acted as the expedition’s

first sergeant. He issued daily provisions after camp was set up in

the evening. Rations were cooked and a portion kept for consumption

the next day. (No cooking was permitted during the day.) Sergeant Ordway

also appointed guard and other details. The guard detail consisted of

one sergeant, six privates, and one or more civilians – fully one

third of the entire party. The guard detail established security upon

landing and maintained readiness throughout the encampment. All three

sergeants maintained duty rosters for the assignment of chores to the

five messes. The cooks and a few others with special skills were exempted

from guard duty, pitching tents, collecting firewood, and making fires.

Drouillard was the principal hunter and usually set out in the morning

with one or more privates and rejoined the expedition in the evening

with meat.

The expedition generally made good time up the Missouri River. Thanks

largely to the total commitment of the crews, the keelboat and pirogues

averaged a bit more than one mile per hour against the strong Missouri

current. With a wind astern, the crews usually doubled their speed.

Along the way, the expedition conquered every navigational hazard the

Missouri River offered. In addition, the men also overcame a variety

of physical ills: boils, blisters, bunions, sunstroke, dysentery, fatigue,

injuries, colds, fevers, snakebites, ticks, gnats, toothaches, headaches,

sore throats, and mosquitoes. As the expedition traveled north, its

members became the first Euro-Americans to see some remarkable species

of animal life: mule deer, prairie dog, and antelope. Wildlife became

more abundant as the expedition moved upriver. The likelihood of meeting

traders and Indians also increased.

As the men traveled north, they encountered more than a dozen parties

of traders, sometimes accompanied by Indians, coming downriver on rafts

or in canoes loaded with pelts. On 26 June the expedition reached the

mouth of the Kansas River. On 21 July, some six hundred miles and sixty-nine

days upstream from Camp River Dubois, the expedition reached the mouth

of the Platte River. On 28 July Drouillard returned from hunting with

a Missouria Indian. The next day Lewis and Clark sent boatman “La

Liberte” (Jo Barter) with the Indian to the Oto camp with an invitation

for their chiefs to come to the river for a council.

At Council Bluff on Friday morning, 3 August 1804, the expedition held

its first meeting with six chiefs of the Oto and Missouria tribes. This

amicable council set the pattern for later meetings between the expedition

and Native Americans. The outstanding characteristic of these councils

was the mutual respect between the expedition and its native hosts.

At midmorning, under an awning formed by the keelboat’s main sail

and flanked by the American flag and troops of the expedition, Captains

Lewis and Clark awaited the Indian chiefs. The two captains wore their

regimental dress uniform, as did Sergeants Ordway, Floyd, and Pryor,

Corporal Warfington, and the twenty-nine privates. As the Oto and Missouria

delegation approached, the soldiers came to attention, shouldered their

arms, dressed right, and passed in review. Captain Lewis then stepped

forward to deliver his long speech announcing American sovereignty over

the Louisiana Territory, declaring that the soldiers were on the river

“to clear the road, remove every obstruction, and make it a road

of peace,” and urging the Oto and Missouria tribes to accept the

new order. According to Private Gass, the chiefs were “well pleased”

with what Lewis said and promised to abide by his words. The chiefs

and officers then smoked the peace pipe and Lewis distributed peace

medals and other gifts to the chiefs. The council closed with a demonstration

of the expedition’s air gun, designed to awe the Indians. Like

a BB gun, the air gun operated by air pressure, was nearly silent, and

was capable of firing a .31-caliber round forty times before recharging.

Upon conclusion of the council, the expedition continued upriver.

Tragedy struck the expedition on 20 August when Sgt. Charles Floyd

died of what modern medical authorities believe was peritonitis from

a perforated or ruptured appendix. Floyd had been ill for some weeks,

but nothing Lewis or Clark did seemed to help. On 19 August he became

violently ill and was unable to retain anything in his stomach or bowels.

Lewis stayed up most of the night ministering to him, but Floyd passed

away just before noon the next day. That afternoon the expedition buried

Floyd with full military honors near Sioux City, Iowa, on the highest

hill overlooking a river the men named in tribute to their stricken

comrade. Sgt. Charles Floyd was the only member of the Lewis and Clark

Expedition to lose his life. Two days later the captains ordered the

men to choose Floyd’s replacement. Pvt. Patrick Gass received nineteen

votes, while Pvts. William Barton and George Gibson each received five.

In their orders of 26 August, Lewis and Clark appointed Patrick Gass

to the rank of sergeant in “the corps of volunteers for North Western

Discovery.” This was the first time the captains used this term

to describe the expedition.

The Corps of Discovery entered Sioux country on 27 August near Yankton,

South Dakota. As the boats passed the mouth of the James River, a young

Indian boy swam out to meet one of the pirogues. When the expedition

pulled to shore, two more Indian youth greeted them. The boys informed

Lewis and Clark that a large Sioux village lay not far up the James

River. Anxious to meet the Yankton Sioux, the captains sent Sergeant

Pryor and two Frenchmen with the Indians to the Sioux village. They

received a warm welcome and arranged for the chiefs to meet Captains

Lewis and Clark. On the morning of 29 August, the Corps of Discovery

met the Yankton Sioux, with both parties dressed in full regalia. As

the Sioux approached the council, the soldiers came to attention, raised

the American flag, and fired the keelboat’s bow swivel gun. The

Yanktons also had a sense of drama. Musicians playing and singing preceded

their chiefs as they made their way to the American camp. After greeting

one another, Lewis gave his basic Indian speech. When he finished, the

chiefs said they would need to confer with the tribal elders. Lewis

was learning Indian protocol, which required of him patience and understanding.

The captains then presented the chiefs with medals, an officer’s

coat and hat, and the American flag. After the formalities were over,

young Sioux warriors demonstrated their skill with bows and arrows.

The soldiers handed out prizes of beads. In the evening the men built

fires, around which the Indians danced and told of their great feats

in battle. The Corps of Discovery was truly impressed with the peaceful

Yankton Sioux. Later, the same could not be said about the Teton Sioux.

From the time they had left St. Louis, Captains Lewis and Clark knew

they would eventually have to face the aggressive Teton Sioux. Careful

diplomacy would be required. On one hand, the Teton Sioux had a bad

reputation for harassing and intimidating traders and demanding toll.

On the other hand, of all the tribes known to Jefferson, it was the

powerful Teton Sioux whom he had singled out in his instructions for

special attention. Jefferson urged Lewis and Clark “to make a friendly

impression” upon the Sioux. Acutely aware of the often-violent

tactics the Teton Sioux used to control the Upper Missouri, the expedition,

in Clark’s words, “prepared all things for action in case

of necessity.”

On the evening of 23 September, just below the mouth of the Bad River

(opposite present-day Pierre, South Dakota), three Sioux boys swam across

the Missouri River to greet the Corps of Discovery. Anxious to begin

talks, the captains told the boys that their chiefs were invited to

a parley the following day. But the next afternoon, as the Corps of

Discovery was preparing for the council, Pvt. John Colter (who had gone

ashore to hunt) reported that some Teton warriors had stolen one of

the expedition’s horses. Suddenly, five Indians appeared on shore.

As the captains tried to speak with the Indians, they realized that

neither group understood the other. Later that evening, Lewis met with

some of the Sioux leaders, who promised to return the horse. In his

journal, Lewis reported “all well” with the Sioux.

Early on Tuesday morning, 25 September, on a sandbar in the mouth of

the Bad River, the Corps of Discovery met the leaders of the Teton Sioux:

Black Buffalo, the Grand Chief; the Partisan, second chief; Buffalo

Medicine, third chief; and two lesser leaders. The council opened on

a generous note, with soldiers and Indians offering food to eat. By

ten o’clock both banks of the river were lined with Indians. At

noon the formalities began. Lacking a skilled interpreter, Lewis made

a much shorter speech, but one that upheld the essential elements established

in his earlier talks. After the Corps of Discovery marched by the chiefs,

Lewis and Clark presented them with gifts suited to their stature. Evidently

unaware of factional Sioux politics, the captains inadvertently slighted

the Partisan and Buffalo Medicine. The chiefs complained that their

gifts were inadequate. Indeed, they demanded that the Americans either

stop their upriver progress or at least leave with them one of the pirogues

loaded with gifts as tribute. Hoping to divert their attention, Lewis

and Clark took the three chiefs in one of the pirogues to the keelboat,

where Lewis demonstrated his air gun. Unimpressed, the chiefs repeated

their demands. After some whiskey, the Partisan pretended to be drunk.

Fearing a bloody melee, Clark and three men struggled to get the Indians

ashore. When the pirogue landed, three young warriors seized the bow

cable. The Partisan then moved toward Clark, speaking roughly and staggering

into him. Determined not to be bullied, Clark drew his sword and alerted

Lewis and the keelboat crew to prepare for action. Suddenly, soldiers

and Indians faced each other, arms at the ready. A careless action by

an individual on either side might have touched off a fight that might

have destroyed the expedition. Fortunately, the members of the corps

held their fire, and Lewis, Clark, and Black Buffalo calmed the situation.

Over the next two days both sides tried to ease tensions. The Sioux

held an impressive ceremony at their village on the evening of 26 September.

After Black Buffalo spoke, he said a prayer, lit the peace pipe, and

offered it to Lewis and Clark. After the solemnities were over, the

Corps of Discovery was treated to all of the Sioux delicacies, and hospitality

reigned in the camp. At nightfall, a huge fire was made in the center

of the village to light the way for musicians and dancers. Sergeant

Ordway found the music “delightful.” Shortly after midnight

the chiefs ended the festivities and returned with Lewis and Clark to

the keelboat, where they spent the night. The next day Lewis and Clark

made separate trips to the Sioux villages and presented more gifts.

On 28 September, as the Corps of Discovery made final preparations for

departure, Black Buffalo and the Partisan made their now-familiar demand

that the expedition remain with them. Both Lewis and Clark were weary

of the constant demand for gifts and sensed trouble from the well-armed

Sioux warriors lining the banks of the river. After an angry exchange

of words, Lewis tossed some tobacco to the Indians. Realizing that he

could not keep the expedition from leaving, Black Buffalo ended the

confrontation and allowed the boats to pass.

News of the Expedition’s confrontation with the Teton Sioux spread

rapidly up and down river. Captains Lewis and Clark had demonstrated

sound leadership and bold determination, while the training, discipline,

and teamwork of the men had gained them much prestige. While the success

of the expedition at Bad River was due in large part to Chief Black

Buffalo, who sought to avoid bloodshed, the fact that the Sioux had

permitted the Americans to pass gave hope to the tribes of the upper

Missouri. Between 8 and 12 October, the Corps of Discovery visited the

Arikara villages in north central South Dakota. The councils went smoothly:

The Arikara chiefs were pleased with their gifts and amazed with the

air gun, while the captains learned much about the surrounding country

and its tribes. On 26 October, five days after the first snow fell,

the expedition arrived near the junction of the Knife and Missouri Rivers,

roughly sixty miles upstream from present-day Bismarck, North Dakota,

and 1,600 miles from Camp River Dubois. This was the home of the Mandan

and Hidatsa tribes.

Described as “the central marketplace of the Northern Plains,”

the five Mandan and Hidatsa villages attracted many Europeans and Indians

alike. With a population of nearly 4,400, this was the largest concentration

of Indians on the Missouri River. After visiting all five villages,

Lewis and Clark prepared for their important council scheduled for 28

October. This would be the largest council yet, bringing together leaders

from the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara tribes. That Sunday weather prevented

Lewis and Clark from holding their meeting, so the captains spent the

day entertaining the chiefs who had arrived and reconnoitering the Missouri

River for a good location for their winter quarters. On 29 October,

just three days after arriving, Captains Lewis and Clark held their

most impressive council to date. After the usual display of American

military prowess, Lewis gave a speech that not only stressed American

sovereignty, but also sought harmonious relations among the tribes themselves.

Next came the distribution of gifts to the chiefs. Then Lewis ended

the proceedings with a display of his air gun, “which appeared

to astonish the natives very much.”

With the onset of winter, the Corps of Discovery had to find a suitable

place for their camp. On 2 November, Captain Clark selected a site directly

opposite the lower of the five Indian villages and two miles away from

it. The next day the Corps of Discovery set to work building a triangular-shaped

structure that consisted of two converging rows of huts (or rooms),

with storage rooms at the apex (the top of which provided a sentry post)

and a palisade with gate at the base or front. The walls were about

eighteen feet high, and the rooms measured fourteen feet square. The

men finished the fort on Christmas Day 1804 and named it Fort Mandan

in honor of their neighbors. For security, the captains mounted the

swivel cannon from the bow of the keelboat on the fort, kept a sentry

on duty at all times, refused Indians admittance after dark, and kept

the gate locked at night.