The U.S. Army and the Lewis & Clark

Expedition

Part 2: President Jefferson's Vision

Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence and third

president of the United States, did much to help create the new nation.

Perhaps his greatest contribution was his vision. Even before he became

president, Jefferson dreamed of a republic that spread liberty and representative

government from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean. As one of the

leading scientific thinkers of his day, he was curious about the terrain,

plant and animal life, and Indian tribes of the vast, unknown lands

west of the Mississippi River. As a national leader, he was interested

in the possibilities of agriculture and trade in those regions and suspicious

of British, French, Spanish, and Russian designs on them.

On 18 January 1803, months before President Jefferson had acquired

the region from France through the famous Louisiana Purchase, he sent

a confidential letter to Congress, requesting money for an overland

expedition to the Pacific Ocean. Hoping to find the Northwest Passage,

Jefferson informed Congress that the explorers would establish friendly

relations with the Indians of the Missouri River Valley, help the American

fur trade expand into the area, and gather data on the region’s

geography, inhabitants, flora, and fauna.

To

conduct the expedition, Jefferson turned to the U.S. Army. Only the

military possessed the organization and logistics, the toughness and

training, and the discipline and teamwork necessary to handle the combination

of rugged terrain, harsh climate, and potential hostility of the endeavor.

The Army also embodied the American government’s authority in a

way that civilians could not. Indeed, the Army provided Jefferson with

a readily available, nationwide organization that could support the

expedition — no small consideration in an era when few national

institutions existed. Although the expedition lay outside the Army’s

usual role of fighting wars, Jefferson firmly believed that in time

of peace the Army’s mission went beyond defense to include building

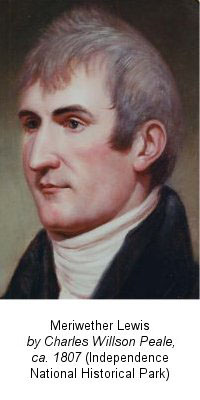

the nation. Finally, the man that Jefferson wanted to lead the expedition

was an Army officer: his personal secretary, Capt. Meriwether Lewis.

To

conduct the expedition, Jefferson turned to the U.S. Army. Only the

military possessed the organization and logistics, the toughness and

training, and the discipline and teamwork necessary to handle the combination

of rugged terrain, harsh climate, and potential hostility of the endeavor.

The Army also embodied the American government’s authority in a

way that civilians could not. Indeed, the Army provided Jefferson with

a readily available, nationwide organization that could support the

expedition — no small consideration in an era when few national

institutions existed. Although the expedition lay outside the Army’s

usual role of fighting wars, Jefferson firmly believed that in time

of peace the Army’s mission went beyond defense to include building

the nation. Finally, the man that Jefferson wanted to lead the expedition

was an Army officer: his personal secretary, Capt. Meriwether Lewis.

A friend and neighbor of Jefferson’s, the 28-year-old Lewis had

joined the Virginia militia to help quell the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794

and then had served for eight years as an infantry officer and paymaster

in the Regular Army. In Lewis, Jefferson believed he had an individual

who combined the necessary leadership ability and woodland skills with

the potential to be an observer of natural phenomena.