Historic Vignettes

- History of the Engineer Castle

- Technician Third Grade Harold F. Sabath

- Army Values

- Private Vinton Dove

- Sergeant Paul Smithhisler

- Specialist Fourth Class Eugene Buckley

- Private Junior Van Noy

- Captain Chris J. Brous

- Private Hubert Webb

- Specialist Fifth Class Richard Friend

- Private James D. McRacken

- Private First Class Philip George

- First Lieutenant Orville Munson

- Sergeant Major Frederick W. Gerber

- SP4 Marvin Miller

- Private First Class David Hutchinson

- Private First Class Herman C. Wallace

History of the Engineer Castle

The medieval castle is inseparably connected with fortifications and architecture. In heraldry, the castle and the tower are often used on coats of arms . In this country the term "castle" has been applied to the strongest of our early fortifications such as Castle Pickney in Charleston, South Carolina, and Castle Williams and Clinton in New York Harbor.

The Corps of Engineers castle is a highly stylized form without decoration or embellishment. The Army officially adopted the castle to appear on the Corps of Engineers Epaulets and belt plate, in 1840. Soon afterwards the cadets at West Point, all of whom were part of the Corps of Engineers until the Military Academy left the charge of the Chief of Engineers and came under the charge of the Army at Large in 1866, also wore the castle on their cap beginning in 1841. Subsequently the castle appeared on the shoulder knot; on the saddle cloth, as a collar device, and on the buttons. although its design has changed many times since its inception, the castle has remained the distinctive symbol of the Corps of Engineers.

Technician Third Grade Harold F. Sabath

In January of 1943 three Engineers from the 1138th Engineer Combat Group were detailed to assist the 81st Infantry Division with amphibious training at San Luis Obispo, California. Missouri native Harold Sabath was one of these Engineers. As storm clouds rose on the horizon and the waves grew, Harold Sabath's sense of duty would be tested.

In January of 1943 three Engineers from the 1138th Engineer Combat Group were detailed to assist the 81st Infantry Division with amphibious training at San Luis Obispo, California. Missouri native Harold Sabath was one of these Engineers. As storm clouds rose on the horizon and the waves grew, Harold Sabath's sense of duty would be tested.

The rough seas threw the small inflatable 10 man boats around. As T/3 Sabath successfully navigated his boat to shore, he noticed another boat capsize in the surf zone. The powerful currents prevented the infantrymen from swimming to shore and slowly drug them toward a coral reef. As a few men rushed for a distant lifeboat, others watched in aghast as the turbulent seas carried the survivors toward the razor sharp rocks.

Before World War II Sabath had been a Red Cross lifeguard. He felt that as a certified lifeguard he possessed the skill to save the men, and knew it was his obligation to attempt a rescue. He tied a rope around his waist and dove into the rough surf. Swimming under water he reached the 10 men at the capsized rubber boat. He ordered all to kick their legs. With the effort of the now motivated survivors and the soldiers on shore pulling the rope tied to Sabath's waist, the stricken life boat edged toward the beach. Exhausted from the cold and exertion, three men separated from the boat and drifted back out to sea.

Realizing these men would surely drown, Sabath let go of the boat as it reached the shore and pursued the distressed soldiers. He managed to reach all three and secured one with each arm, while the third climbed on his back. Others on shore used the rope to pull all four men to land.

By living up to all the Army Values, Sabath's saved the lives of ten soldiers. For his actions, Technician Third Grade Harold Sabath was awarded the Soldier's Medal.

Army Values

Loyalty

Bear true faith and allegiance to the U.S. Constitution, the Army, your unit and other Soldiers. Bearing true faith and allegiance is a matter of believing in and devoting yourself to something or some-one. A loyal Soldier is one who supports the leadership and stands up for fellow Soldiers. By wearing the uniform of the U.S. Army you are expressing your loyalty. And by doing your share, you show your loyal-ty to your unit.

Duty

Fulfill your obligations. Doing your duty means more than carrying out your assigned tasks. Duty means being able to accomplish tasks as part of a team. The work of the U.S. Army is a complex combination of missions, tasks and responsibilities — all in constant motion. Our work entails building one assignment onto another. You fulfill your obligations as a part of your unit every time you resist the temptation to take “shortcuts” that might undermine the integrity of the final product.

Respect

Treat people as they should be treated. In the Soldier's Code, we pledge to “treat others with dignity and respect while expecting oth-ers to do the same.” Respect is what allows us to appreciate the best in other people. Respect is trusting that all people have done their jobs and fulfilled their duty. And self-respect is a vital ingredient with the Army value of respect, which results from knowing you have put forth your best effort. The Army is one team and each of us has some-thing to contribute.

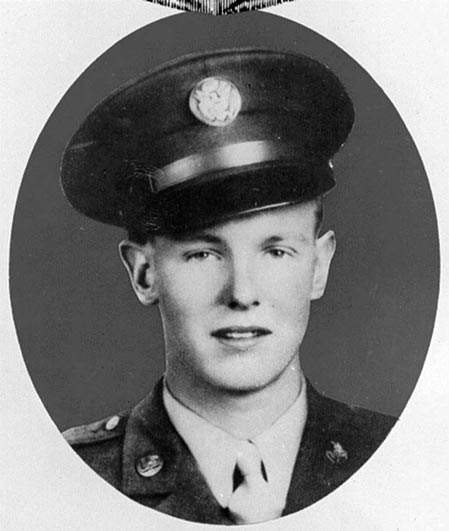

Private Vinton Dove

Private Vinton Dove entered the Army at Fort Myer, VA, in September 1943. Following bull dozer operator training, he was assigned to the 37th Engineer Battalion. On D-Day, Private Dove and his assistant operator, Private Shoemaker, were in a Landing Craft Mechanized (LCM) heading for Omaha Beach. The LCM contained two jeeps in front of Dove and Shoemaker's bulldozer, and several squads of Infantry. As the LCM's ramp dropped, machinegun fire raked the LCM, killing the two jeep operators and most of the Infantry. Dove threw the dozer into gear and pushed the two jeeps ahead of it into the surf. Sixteen bulldozers were slated to land on Omaha Beach early on D-Day. Only six made it ashore, and three of those were destroyed by German mortars and artillery.

Sitting atop the dozer, Dove and Shoemaker were chest deep in seawater. After pulling several disabled vehicles out of the surf and removing many obstacles with the dozer, the two Engineers headed for the beach. Rifle and machinegun fire was so intense that Dove operated the dozer lying nearly horizontal, while clearing mines and obstacles from the beach. Later that morning, an Infantryman requested Dove's assistance in taking out a German machinegun.

Dove's next task was to clear the narrow road designated Exit E-3. The road was blocked with cars, trucks, and even a cement mixer. Dove moved up the road pushing the obstacles over the road's edge. As Dove crested a hill, he spotted a German soldier, and dispatched the German with a single rifle shot.

Next, Dove had to clear a shingle and fill a tank trap to reach Exit E-1. The bulldozer slowly moved up a hill clearing E-1 of obstacles. At the crest of the hill, sniper fire caused Dove to dismount his dozer. Once the Infantry silenced the sniper, Dove cut a road inland through a field and hedgerows for over a mile. Despite being shot in the hand and having shrapnel in his face and lips, Dove continued to operate his dozer for over 48 hours. For his actions on June 6, 1944, Private Vinton Dove was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

Sergeant Paul Smithhisler

In late October 1918 Allied units had repeatedly tried to cross the Escaut River in Belgium. Accurate German machine guns and artillery fire had blunted several assaults. After several units had failed the mission was assigned to the 37th Infantry Division. The 112th Engineer Regiment put out a call for volunteers to conduct a reconnaissance of the German positions on the far bank of the river.

Sergeant Paul Smithhisler, a draftsman in Headquarters Company, volunteered. Under the cover of darkness, just before midnight on November first Sergeant Smithhisler eased down the steep muddy bank and into the icy cold water. Private Burke, another volunteer, remained behind to assist the Sergeant up the river bank and provide cover if necessary, upon his return. Sergeant Smithhisler.

In late October 1918 Allied units had repeatedly tried to cross the Escaut River in Belgium. Accurate German machine gun and artillery fire had blunted several assaults. After several units had failed the mission was assigned to the 37th Infantry Division. The 112th Engineer Regiments put out a call for volunteers to conduct a reconnaissance of the German positions on the far bank of the river.

Sergeant Paul Smithhisler, a draftsman in Headquarters Company, volunteered. Under the cover of darkness, just before midnight on November first Sergeant Smithhisler eased down the steep muddy bank and into the icy cold water. Private Burke, another volunteer, remained behind to assist the Sergeant up the river bank and provide cover if necessary, upon his return. Sergeant Smithhisler crossed the 100 foot wide swiftly flowing river without being detected. Evading sentries and patrols, he sketched the precise location of artillery positions and machine gun nests along a 500 meter front. Stowing the drawing into a waterproof pouch, Smithhisler made his way back towards the river. The approaching dawn allowed the Germans to detect Sergeant Smithhhisler as he returned to the river. The Sergeant swam quickly, but the sentries alarm brought a hail of machine gun fire. Taking a gasp of air Sergeant Smithhisler swam the remainder of the river underwater.

Realizing the Sergeant probably possessed information extremely detrimental to their cause, the Germans called in an artillery barrage, containing both high explosive and poison gas rounds. Sergeant Smithhisler emerged from the water panting for air, just as the deadly gas arrived. Completely exhausted and feeling the effects of the gas, Smithhisler was unable to don his mask. Private Burke pulled his sergeant to safety and placed a mask on him, before succumbing to the gas himself. Thought mortally wounded, Burke's actions saved the life of Sergeant Smithhisler.

Sergeant Smilthhisler recovered from his wounds. On January 28, 1919 General Pershing inspected the 112th Engineers at Alencon, France. Following the inspection Sergeant Smithhisler was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and the French Croix de Guerre with Silver Star.

Specialist Fourth Class Eugene Buckley

Just after dusk on April 16th 1968, the 1st Engineer Battalion was tasked to cut a landing zone for a Vietnamese Army (ARVN) unit. The ARVN unit had taken heavily casualties and was still engaged and surrounded by the enemy. Several dozen severe casualties required immediate evacuation. Specialist Buckley, who was a Combat Engineer, and another soldier volunteered for the rescue mission. At 2:00 a.m., both soldiers were lowered from a helicopter, with a chainsaw and several axes, into the jungle near Tan Uyan, Vietnam.

The ARVN perimeter was under constant enemy rifle and machinegun fire. Even though the noise from his chainsaw drew more enemy fire, Specialist Buckley continued clearing the much needed landing zone.

He continued to enlarge the clearing and directed other soldiers to assist with the axes. After hours of intense labor, the landing zone was large enough to allow helicopters to land. Fifty casualties were evacuated before concentrated enemy fire prohibited further use of the landing zone. Buckley was forced to remain with the ARVN unit that fought its way out over the next few days. Buckley's actions saved many lives and for these actions he was awarded the Silver Star Medal. The citation reads, “For gallantry in action while engaged in military operations involving conflict with an armed hostile force in the Republic of Vietnam: On this date (17 April 1968), Specialist Buckley was serving with his engineer company. His unit was requested to provide assistance for a regiment of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam which desperately needed to have a landing zone cut in the thick jungle near its night defensive position to facilitate the evacuation of approximately 50 casualties. Specialist Buckley unhesitatingly volunteered for the mission, although he realized it involved being airlifted into hostile territory in darkness. At approximately 0200 hours, he was lowered from a hovering helicopter by a 60 foot rope into the jungle near Tan Uyan. The South Vietnamese defensive position was receiving continuous small arms fire at this time, and he was an extremely vulnerable target during his descent into the unsecured area. Specialist Buckley contacted the friendly elements and worked throughout the night to clear the vital landing zone. During this time he was continuously engaged by hostile fire, but this did not deter him from completing the task. His courageous initiative and calm perseverance were major factors enabling the numerous casualties to be evacuated from the remote area. Specialist Four Buckley's unquestionable valor while engaging in military operations involving conflict with an insurgent force is in keeping with the finest traditions of the military service and reflects great credit upon himself, the First Infantry Division, and the United States Army.”

By volunteering to go on this rescue mission and risking his own personal safety to save many lives of our Vietnamese allies, Specialist Buckley exercised the Army Value of personal courage.

Private Junior Van Noy

In the fall of 1943, Engineers from the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade supported Australian forces in a landing at Finschafen, New Guinea. The joint force quickly overcame enemy resistance and opened the nearby airfield.“For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty in action with the enemy near Finschafen, New Guinea, on 17 October 1943. When wounded late in September, Pvt. Van Noy declined evacuation and continued on duty. On 17 October 1943 he was gunner in charge of a machinegun post only 5 yards from the water's edge when the alarm was given that 3 enemy barges loaded with troops were approaching the beach in the early morning darkness. One landing barge was sunk by Allied fire, but the other 2 beached 10 yards from Pvt. Van Noy's emplacement. Despite his exposed position, he poured a withering hail of fire into the debarking enemy troops. His loader was wounded by a grenade and evacuated. Pvt. Van Noy, also grievously wounded, remained at his post, ignoring calls of nearby soldiers urging him to withdraw, and continued to fire with deadly accuracy. He expended every round and was found, covered with wounds dead beside his gun. In this action Pvt. Van Noy killed at least half of the 39 enemy taking part in the landing. His heroic tenacity at the price of his life not only saved the lives of many of his comrades, but enabled them to annihilate the attacking detachment.”

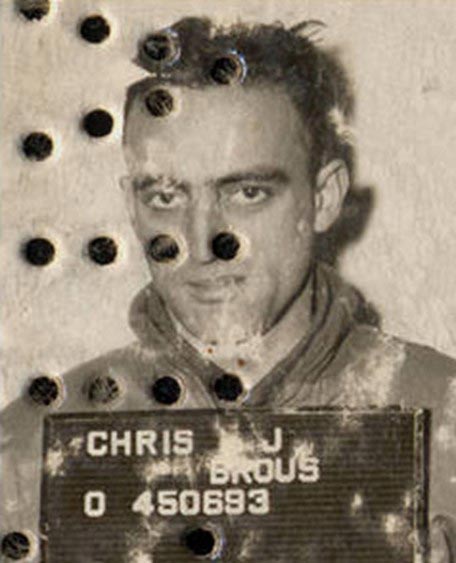

Captain Chris J. Brous

In the early morning hours of August 2, 1944, Captain Chris J. Brous was returning from inspecting his front line troops. As his jeep rounded a turn in the road, it was struck by tank and machine gun fire, killing the driver. Captain Brous and First Lieutenant McKinney were taken prisoner.

Both Engineer officers were wounded. They were ordered to sit in a nearby field to await transport to a German hospital. Realizing that his field notes might contain information harmful to the Allied cause, Captain Brous tore them into tiny pieces and buried them.

In route to the German hospital, Lieutenant McKinney asked what he should do with his field notes. Captain Brous responded, “You know your orders eat them!” At the hospital, the German surgeons removed 16 shell fragments from Captain Brous' left thigh and chest. He was then sent to a German hospital in Paris. On August 18th, Captain Brous and 80 other Allied prisoners were taken to a train station for transport to a Prisoner of War (POW) camp in Germany.

Captain Brous made contact with the French Underground through a worker at the station. They arranged to shoot up the train engine pulling the POW train. Concerned that the train might be accidently attacked by Allied aircraft, Captain Brous asked the German guards for permission to paint red crosses on the train cars.

The POW train was liberated by Free French troops on August 22nd.

Captain Brous was awarded the Bronze Star and Purple Heart Medals for his actions. After rehabilitating at an Army hospital in England, Captain Brous insisted on rejoining the 23rd Engineers. Captain Brous exercised the Army Value of Integrity by doing what was legally and morally right. His actions of destroying his field notes, directing Lieutenant McKinney to eat his notes, ordering the destruction of the train engine, and marking the train with a red cross to ensure the safety of the soldiers were legally and morally correct. These actions promoted the Allied cause while impeding the German efforts.

In route to the German hospital, Lieutenant McKinney asked what he should do with his field notes. Captain Brous responded, “You know your orders, eat them!” At the hospital, the German surgeons removed 16 shell fragments from Captain Brous' left thigh and chest. He was then sent to a German hospital in Paris. On August 18th, Captain Brous and 80 other Allied prisoners were taken to a train station for transport to a Prisoner of War (POW) camp in Germany.

Private Hubert Webb

Late in the fall of 1944, a patrol of 23 infantrymen and 8 Engineers were sent on a mission across the Saar River to capture an enemy prisoner. The patrol was evenly split between two assault boats. Under the cover of darkness and a rainstorm, the patrol left friendly positions. The patrol managed to reach the far shore, where four Engineers, including Hubert A. Webb, remained with the boats while the rest of the force sought out a prisoner.

The patrol found the enemy's defensive line too strong. Dawn was quickly approaching, so the infantry decided to call off the patrol and return to the boats. Shortly after beginning the return trip, an infantry soldier stepped on a mine. The resulting havoc erased all sense of order among the infantry and aroused the German defenders. Two more infantrymen stepped on mines as the patrol raced for the boats.

Two of the wounded were placed in Webb's boat and the group quickly set out for the safety of the far shore. A little over half-way across, the boat was pulled against the column of a destroyed railroad bridge. The boat spiraled into a whirlpool. After spinning violently for a short time, the boat collided with a large log. The force smashed the boat into pieces which quickly sank. Webb grabbed one of the wounded men and pushed him up onto the debris piled around the bridge column.

The survivors were stranded on the enemy side of the bridge for five days. The morning of the fifth day dawned foggy. Webb spotted an assault boat that had floated downriver and lodged in a debris pile close to the shore. Webb swam into the river and retrieved the assault boat and seven paddles.

On the sixth night, the patrol loaded the two wounded men into the repaired boat and pushed it approximately 75 yards up stream. The Engineers pushed the boat as far as possible into the river, then mounted the boat and rowed as hard as they could. The beleaguered patrol reached the friendly shore near the abutment of the damaged bridge. Mustering what little energy their half-starved bodies contained they attempted to carry the two wounded infantrymen up the river bank. The survivors finally got lucky, and stumbled into a friendly patrol.

By fulfilling his obligations to his unit, and the infantry unit he was supporting, Private Webb exemplified the Army Value of Duty. For his actions Private Webb was awarded the Silver Star Medal.

Specialist Fifth Class Richard Friend

In the early morning hours of Sunday, March 21, 1967, a supply convoy from the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment was going from the Gia Ray Rock Quarry to Saigon. Four Engineers from the 595th Engi-neer Company (Light Equipment) joined the convoy with the hope of locating some much needed repair parts. The convoy contained eight Armored Personnel Carriers (APC) and one tank from the 11th Cavalry Regiment, as well as the Engineers' Jeep and 2 ½ ton truck.

Specialist Five Richard Friend rode shotgun in the jeep, positioned 6th in the order of march, right behind the Engineers' 2 ½ ton truck. Just kilometers outside of Gia Ray, the convoy rolled through the vil-lage of Suoi Cat.

On the far side of the village, the convoy was ambushed by what later was determined to be a North Vietnamese Army (NVA) battalion-sized element. The extremely intense ambush was over a kilometer long, with enemy on both sides of the road, firing machine guns, rocket propelled grenades, and 57mm anti-tank guns. The lead tank hit a mine and threw a track, stopping most of the convoy within the kill zone of the ambush. The jeep driver, Specialist George Heppen, decided to race out of the kill zone, while Friend and another occupant returned fire. The jeep sped 500 yards, but while trying to pass the disabled tank, it was struck by a recoilless rifle round. The jeep veered off the road and struck a tree. Friend was thrown from the passenger's seat and struck the same tree, breaking his nose.

As Friend shook off the mental haze caused by his collision with the tree, he found himself in the middle of an extremely violent and well-prepared ambush, with no helmet, and no weapon. His only solace came from the three-foot-grass, in which his jeep rested. Friend crawled to the road and saw an APC 100 meters down the road. He leapt to this feet and, in a crouched position, ran toward the APC. He quickly saw two NVA soldiers behind a dirt mound. Strangely, the NVA pointed their weapons at Friend, but did not fire.

Now just 50 meters from the APC, Friend saw an NVA soldier running toward the APC carrying a rifle and satchel charge. Friend stated, “I knew he had a rifle, he wasn't using it, and I needed it.” As the two adversaries ran toward the APC with very different goals in mind, other enemy soldiers fired on Friend, but he still managed to close on the NVA soldier with the satchel charge. Friend felt a blow to his chest as an NVA bullet struck a box of M16 ammo in his breast pocket.

As the NVA soldier neared the APC, he dropped his shoulder, sliding the satchel charge off and crept toward the APC. Friend reached for his belt and extracted his hunting knife, closed the distance and drove the hunting knife in the NVA's back. Friend, still with no weapon, climbed on top of the disabled APC and into the safety of its armored crew compartment, only to find everyone inside wounded.

Specialist Friend could have hid in the tall grass and waited for the ambush to be over. Instead he exercised the Army value Selfless Service. Friend placed the welfare of the soldiers in the APC above his own safety, and risked his life to save theirs. For his actions during the ambush, Richard Friend was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

On the far side of the village, the convoy was ambushed by what later was determined to be a North Vietnamese Army (NVA) battalion-sized element. The extremely intense ambush was over a kilometer long, with enemy on both sides of the road, firing machine guns, rock-et propelled grenades, and 57mm anti-tank guns. The lead tank hit a mine and threw a track, stopping most of the convoy within the kill zone of the ambush. The jeep driver, Specialist George Heppen, de-cided to race out of the kill zone, while Friend and another occupant returned fire. The jeep sped 500 yards, but while trying to pass the disabled tank, it was struck by a recoilless rifle round. The jeep veered off the road and struck a tree. Friend was thrown from the passenger's seat and struck the same tree, breaking his nose.

As Friend shook off the mental haze caused by his collision with the tree, he found himself in the mid-dle of an extremely vio-lent and well-prepared ambush, with no helmet, and no weapon. His only solace came from the

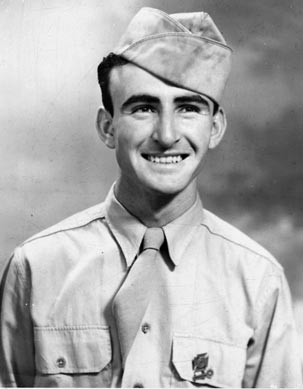

Private James D. McRacken

In October of 1943, James Dougald McRacken left his pregnant wife in his hometown of Red Spring, North Carolina, to answer his nation's call. Following training, McRacken had a short furlough to meet his newborn daughter. On his return, he was assigned to the newly formed Company A, 315th Engineer Battalion, 90th Infantry Division.

On June 6, 1944 (D-Day), the 315th Engineers landed on Utah Beach with the rest of the 90th Division. On August 5th the 315th Engineers were just 130 miles southwest of Paris, on a hill overlooking the small French town of Mayenne. A citizen of Mayenne warned the Engineers that the Germans had rigged Mayenne's only bridge with explosives. If the ancient stone bridge was destroyed, it would drastically slow the Allied advance and leave the people of Mayenne without this essential fixture of infrastructure.

As the Engineers fought their way into town, heavy volumes of German small arms, machine gun, and artillery fire slowed the advance. Knowing the Germans would detonate the explosives at any moment, Private McRacken sprinted the 500-yards to the bridge. Though his body was shattered by gunfire, Private McRacken continued forward and found the main control wire for the German explosive charges. He snipped the wires, then fell and died on the ancient stone bridge.

The French people who watched Private McRacken's death from a hillside came to the bridge, shrouded his body, and covered it with dahlias. He was officially declared the "Savior of Mayenne.” Private McRacken lived up to all the Army Values and his actions allowed the Allies to continue their advance. He was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

Speaking of McRacken's actions, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt said, "He stands in the unbroken line of patriots who have dared to die so that freedom might live, and grow, and increase its blessings. Freedom lives, and through it, he lives - in a way that humbles the undertakings of most men."

Private First Class Philip George

In early Au-gust 1967, Bravo Company, 39th En-gineer Battalion, was tasked with opening a five mile stretch of Robeit-son Road con-necting QL1 to the Chu Lai ferry. The “road,” which was a Viet Cong strong-hold, had been closed since 1954 and resembled an overgrown path.

On 11 August, the First Platoon opened half the road before being ambushed. The ensuing battle took the lives of two Engineers and wounded three more. The next day Captain Wenners sent his entire company to open the road. With the road almost complete, the Engi-neers came under heavy sniper fire and scrambled for cover. When the drivers attempted to move their vehicles, snipers resumed the deadly fire. It became apparent that if the road was not completed and the convoy moved, the enemy would surely mount an all-out attack after dark. Private First Class Philip Alan George volunteered to open the road with his bulldozer. As sniper rounds ricocheted off his bulldozer, George remained at the controls of his machine and fin-ished the road.

When the Engineer convoy started moving, the third truck was hit by enemy fire and became disabled, blocking the road. It could not be moved and blocked the escape of all the vehicles behind it. The snipers began to concentrate their fire on the vehicles behind the disabled truck.

George, who by this time had reached a secure area about a mile down the road, unhesitatingly turned his bulldozer around and drove to the disabled truck. The enemy directed their fire at George in the unprotected bulldozer. Private George hooked onto the vehicle and pulled it through rice paddies, still under enemy fire. His actions allowed the trapped convoy to advance to safety.

Private George displayed honor during the battle by living up to all the Army Values. He was the only soldier in the company with the equipment and training to save the convoy and he exercised the Army Value of Integrity by doing what was morally right. Private George exercised Selfless Service by placing the welfare and safety of his fellow Engineers above his own personal safety. He exercised Personal Courage by facing the danger of heading back into the ambush to assist his fellow team members. Private George was loyal to his unit and fellow soldier; while having faith that his NCOs and Officers would provide cover while he drove his bulldozer back into the ambush. For his living up to all the Army Values, Private George was awarded the Silver Star Medal and the Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry.

First Lieutenant Orville Munson

During the first week of January 1944, the 48th Engineer Battalion struggled to convert a severely damaged railroad into a highway, in support of operations to capture Mount Porchia, Italy. For several days, the Engineers worked on the highway during the day, then were placed into the line as infantry each night.

On the night of January 6th, the 48th Engineer Battalion was directed to capture Mount Porchia. First Lieutenant Orville Munson, Commander of Company A, led his company across several miles of “no-man's-land” and through the battle to capture the hill. For his actions that night, 1st Lt. Munson was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. His citation reads, “1st Lt. Munson led his company in darkness through mined and shelled areas to the foot of Mt. Porchia, Italy. He acted as point of the column and was often far in advance and alone in enemy territory. He encountered two enemy machine gun nests from which he drew fire, but he extricated his company by leading his men in a circular path around the enemy positions. During this action, he killed one German at close range with his submachine gun. Later, he encountered an enemy patrol and was captured. With a gun at his back, he shouted a warning to his men and prevented their walking into an ambush. At this time, a hand grenade exploded nearby, a fragment striking 1st Lt. Munson in the shoulder. He fell to the ground and feigned death. His captors took his submachine gun and left the area. 1st Lt. Munson rose, picked up a carbine and captured two prisoners before returning to his company. The courage displayed by 1st Lt. Munson prevented the ambush of his company and also enabled his men to capture six of the enemy patrol.”

By placing the welfare of his subordinates above his own personal safety and leading his Company through the extremely violent battle, 1st Lt. Munson exhibited the Army Value of Selfless Service.

1st Lt. Munson remained in the Army, completing over 20 years of service. In addition to the Distinguished Service Cross earned on Mount Porchia, Munson earned a Silver Star Medal, two Bronze Star Medals and four Purple Heart Medals.

Sergeant Major Frederick W. Gerber

A native of Dresden, Germany, Frederick Ger-ber arrived in the United States in the 1830s. He joined the 4th Infantry in 1839 but returned to civilian life in 1844. His decision to reenlist when the company of engineers was author-ized in 1846 brought him into the Corps of Engi-neers for the remainder of his life.

In the war against Mexico, Gerber won nu-merous accolades. Dur-ing the Battle for Mexico City, he saved the life of Lt. George B. McClellan, who later served as commander of Union forces during the Civil War. When the city was surrendered to the United States, Gerber was given the honor of sounding the surrender call. During the Civil War, Gerber had the re-sponsibility for molding volunteer recruits into engineer soldiers, training the much needed pontoniers, sappers, miners, and pioneers.

On November 8, 1871, Gerber became the first engineer to receive the Medal of Honor. He was not recognized for any single act of gallantry but for his unparallel performance over many years. His citation reads, “in recognition of long, faithful, and meritorious services covering a period of 32 years.”

Gerber died in 1875. Gerber took great pride in being the senior enlisted man in the Engineers. Offered a commission several times, he declined each offer. As Gilbert Thompson, who served with him, later wrote, “practical and punctilious in all duties, he [Gerber] considered that to be the ranking non-commissioned officer in the Army was a greater honor than to hold a commission.”

Sergeant Major Gerber always performed his duty to the best of his abilities. His Medal of Honor is one of only a handful awarded solely for duty.

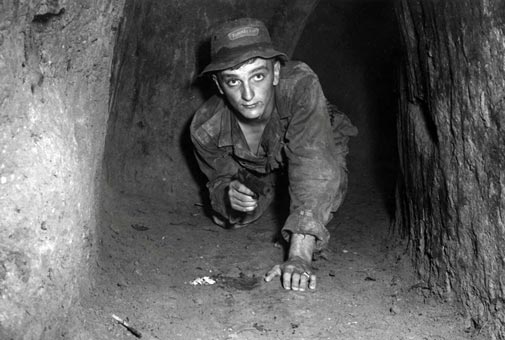

SP4 Marvin Miller

Specialist Fourth Class Marvin Miller had one of the most dangerous jobs in Vietnam-he was a “tunnel rat.” Tunnel rats entered the labyrinth of underground passages to clear enemy forces and set explosives to collapse the tunnels.

In FebruarIn February of 1969, the 1st Infantry Division discovered many tunnel openings near Chu Chi, Vietnam. The 1st Engineer Battalion tunnel rats were called in to investigate. The tunnel rats discovered a huge underground complex. As explosive charges were being set to seal several entrances, the enemy attacked. Miller raced through hostile fire to the scene of the attack. He assisted in carrying the dead and wounded to a medical evacuation point. When it became obvious that the evacuation helicopter could not land, he volunteered to assist with a stabilized body extraction harness (STABO) rescue. Miller and two wounded soldiers were strapped into the harnesses.

harness (STABO) rescue. Miller and two wounded soldiers were strapped into the harnesses. As the helicopter lifted the three, Miller steadied the two wounded soldiers to prevent further injury.

For his actions that day Specialist Fourth Class Marvin Miller was awarded the Army Commendation Medal with “V” device (for valor). In part, his citation reads: “His selfless courage and professional performance of his mission were instrumental in saving several of his comrades' lives and significantly contributed to the successful outcome of the operation.” Specialist Miller exercised selfless service by putting the welfare of the Army and his fellow soldiers before his own.

Private First Class David Hutchinson

Just four days into a year-long tour in Afghani-stan, Private First Class Da-vid R. Hutchinson manned a MK-19 Automatic Gre-nade Launcher in the turret gunners position of the third vehicle in a convoy. The convoy contained 17 soldiers in four vehicles from the 420th Engineer Brigade. As the vehicles passed through a steep mountain pass, 15-20 enemy attacked with Rifle Propelled Grenades (RPG), machine guns, and automatic rifle fire.

From their positions on the high ground the enemy was able to fire down into the Engineer's protective turrets. After striking the first and last vehicles with RPGs the enemy launched a ground assault against the convoy. Hutchinson quickly determined that an enemy machine gun position was the key to the enemy's assault. He directed his MK-19 fire on that position and destroyed it. Enemy fire now con-centrated against Hutchinson. He responded with MK-19 fire against the exposed enemy troops. Hutchinson expended an entire can of ammunition, destroying positions and killing at least 5 enemy soldiers before an RPG struck the crew compartment of his vehicle. RPG shrapnel impacted his right leg and caused him to collapse into the cab of the vehicle.

The convoy was now able to exit the ambush. Laying severely wounded in the crew compartment, Hutchinson noticed his first sergeant had serious wounds to his head, neck, and shoulder. Hutchinson disregarded his own wounds and administered buddy-aid to the wounded first sergeant. By the time the convoy had traveled the 1.5 mile to a medical evacuation site, Hutchinson had stabilized the wounded first sergeant. Once the MEDEVAC helicopter arrived, Hutchinson refused to be carried on a stretcher, and walked to the helicopter. This act freed two additional soldiers to provide security for the evacuation site. Because of the severity of his wounds Private First Class Hutchinson was evacuated back to the United States. Hutchinson was awarded the Silver Star Medal for his actions.

Private First Class Herman C. Wallace

On February 27, 1945, Private First Class Herman C. Wallace was conducting mine clearing operations while assigned to Company B, 301st Engineer Combat Battalion, 76th Infantry Division. While clearing a road near Prumzurley, Germany, Private First Class Wallace gave his life to save the lives of his fellow Engineers. “His citation reads: He displayed conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity. While helping clear enemy mines from a road, he stepped on a well-concealed S-type antipersonnel mine. Hearing the characteristic noise indicating that the mine had been activated and, if he stepped aside, would be thrown upward to explode above ground and spray the area with fragments, surely killing 2 comrades directly behind him and endangering other members of his squad, he deliberately placed his other foot on the mine even though his best chance for survival was to fall prone. Private First Class Wallace was killed when the charge detonated, but his supreme heroism at the cost of his life confined the blast to the ground and his own body and saved his fellow soldiers from death or injury.”