Japanese American War Hero Recalls Life During World War II

U.S. Department of Defense News Article

By Rudi WilliamsAmerican Forces Press Service

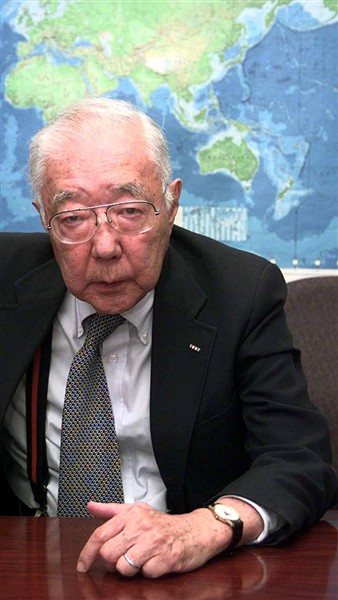

WASHINGTON, May 25, 2000 – World War II hero Yeiichi "Kelly" Kuwayama, 83, was already in the Army when the government started uprooting Japanese Americans and incarcerating them in relocation camps after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor.

Kuwayama had been editing statistics at the Japanese Chamber of Commerce in New York City for six months when his draft notice arrived about a year before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

"When I was drafted, many of my tent mates were lawyers, engineers and other college graduates," said Kuwayama, who graduated with bachelor's degree in politics, economics and history from the prestigious Princeton University School of Public and International Affairs in 1940. He was assigned to New York Harbor defense with a coastal artillery unit.

"An 18-year-old National Guard corporal took us out for exercise every morning," he recalled. "At that time, we had two meals a day and we wore mostly World War I remnants -- wrap-around leggings, wool overseas hats -- and used World War I equipment."

Kuwayama was sent to a coastal artillery unit in New Jersey to be trained on 16-inch guns. But the next morning, a general came around for an inspection, looked at Kuwayama and asked, "What's your name, private?"

"Pvt. Kuwayama, sir," the young soldier responded. And that was the end of his artillery career. The next day, he became a purchasing clerk in an ordnance battalion.

"When the general found out my name was Kuwayama -- a Japanese name -- they got me out of New York and the New York Harbor defense," he said. "After that, they wouldn't send me for officer's training or any other school. I got my sergeant stripes before Pearl Harbor. And even though I spent a lot of time in combat, was wounded and received the Silver Star, I never got promoted again."

But he did get a name change. The first sergeant couldn't pronounce Kuwayama, so he said, 'I'm going to change your name. Do you have any preferences? "

"I said, no," Kuwayama recalled.

"Do you mind if I chose one," the first sergeant asked.

"No, not at all," Kuwayama responded.

"How about Kelly?" the first sergeant asked.

"Well, that's fine," Kuwayama answered.

"From now on, you're Kelly," the first sergeant said. "And anytime I say Kelly, you say, 'Here, Sir!'"

From then on, whenever Kuwayama met new people, he told them his name was "Kelly." He still does today.

"I got tired of having to spell my name for people," said Kuwayama. "It's easier for everybody to call me 'Kelly.'"

After a short stint as a clerk, he became a hospital orderly and then a surgical technician and instructor.

"The strange thing was, I was a surgical technician, but I was never sent to a surgical tech school," Kelly said. "They sent about 10 guys to me from Fort Devens, Mass., every 30 days for me to teach them operating room techniques. I'd read a chapter of a manual at night and spew it out to those guys the next day. There I was, teaching them while I was teaching myself."

A short time later, Kuwayama found out the Army was forming an all-Japanese American unit, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. He volunteered and was sent for training at Camp Shelby, Miss., in 1943.

"I saw more Japanese Americans than I'd ever seen in my life, mostly from Hawaii," he said. "There were about 10,000 volunteers from Hawaii, but they only took about 3,000. Most of the rest came from the internment camps in Oregon, Utah, Arizona, Washington and California. The government called them relocation camps, but the people in them called them concentration camps."

Following a short stay in a battalion aid station, Kelly was assigned to a rifle company as a medic shortly before the 442nd was sent overseas.

"The 442nd landed in May 1944 at Naples, Italy, and went into the lines right above Rome," Kelly said. "The 100th Infantry Battalion, mostly Japanese American National Guardsmen from Hawaii, had been there about a year before we arrived. They'd suffered tremendous casualties fighting in Cassino and Anzio."

The 100th, the first all-Japanese American combat unit, led by white officers, merged with the 442nd. "But they wanted to retain their name since they'd spent a year in combat and had established a great record," Kelly said. "So they retained the name of the 100th, even though they were our first battalion. I was with Company E of the 2nd Battalion."

The 442nd fought up the mountainous boot of Italyn, Kelly said. "The Germans used machine guns and mortars to pin us down, but we'd take one hill after another and climb up the boot," he noted. "We were then assigned to Southern France after the Normandy invasion."

Kelly's most harrowing experience came when the 442nd was assigned to rescue "The Lost Battalion" -- the 1st Battalion, 141st Infantry Regiment, 36th Division, formerly of the Texas National Guard.

"We rescued them, but we had tremendous casualties," Kelly said. "We were just about blown apart on the final assault." The 442nd rescued 211 survivors in three days at a cost of about 800 dead and wounded.

Kelly was wounded during the grueling rescue on Oct. 29, 1944. He said he was hit in the head by shrapnel while he was trying to rescue a wounded comrade. After two weeks in the hospital, he returned to the 442nd, which had been transferred in the meantime to the Maritime Alps between France and Italy.

His Silver Star citation states Kelly crawled across open ground swept by enemy fire, took the shrapnel wound and, though partially blinded by his own blood, reached his fallen comrade and calmly administered first aid. He then dragged the man to safety through a hail of mortar and machine gun fire.

Kelly said his worst combat experiences were the nights, when replacements arrived. "I would shake the hands of the guys coming in knowing that by the next day I might be picking them up dead," he said. "They were replacing our men who had been hit that day. I knew these guys were scared. They were also very anxious not to let the unit down. When you're advancing on the line, the guy in the front is going to be picked off. They were so anxious they were raring to be the first to go and would be the first to get killed. It was tough to meet these guys.

"When I looked at them and their eyeballs didn't move, I knew they were dead. That was tough," Kelly said.

But there were good times, too. "The Italians were very friendly," Kelly said. "They didn't have much food, but they'd invite us to family dinner to share what they had. You'd sit with the farmer and his family. They'd just have one big pot, usually a stew with meat, potatoes and vegetables. The man of the house would scoop out stuff, put it on a plate and pass it around. Then he'd peel off a piece of bread for everyone.

"To be able to eat with a family was a big deal," Kelly said. "All we got every night was K rations, which were canned eggs and three crackers, canned cheese and three crackers, or Spam, some kind of luncheon meat, and three crackers. There would also be little packages of powdered orange juice, soup or coffee. Being in a rifle company, you'd only get a hot meal maybe once a week most of the time under the best conditions."

More than 110,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast were held in relocation camps scattered around the country. Kelly said his family and other Japanese Americans on the East Coast were not, but that didn't make their lives any easier.

"Most of the Japanese Americans were domestics and were fired from their jobs. Nobody would hire them," Kelly said. "A few of the people they worked for stuck by them, but it was hard for those who were let go. I heard rumors that some of them committed suicide."

Kelly's father was an entrepreneur, but he didn't have much business after Pearl Harbor. "People would yell insults at him and wouldn't spend any money in his business," he noted.

His father came to America aboard a freighter in 1890, landed in San Francisco and later made it to New York City on another freighter.

"He didn't have much money," Kelly noted. "My father told me he got his first piece of bread in America out of a garbage can. He wasn't much of a cook, but a mission helped him get a job as a cook for J. Walter Thompson, a pioneer in the advertising industry. Thompson's advertising agency was the first to develop artwork, photographs, recipes, color pictures and copy for clients."

Kelly said a maid noticed that his father didn't cook well, but, with her help and a cookbook, he learned.

The elder Kuwayama saved his money and later started an employment agency for cooks, butlers, drivers and gardeners. He opened an American-style restaurant, invested in the stock market and made a fortune. He returned to Japan to get married and found his stock fortune wiped out when he came back to the United States. He then added a Japanese restaurant to make ends meet.

"My mother didn't want to work in a restaurant, so my father bought a Japanese grocery and art goods store," Kelly said. His father earned enough money to send his children to college. Kelly's older sister, Aya, now 84, is a retired restaurateur living in New Town, Pa. His younger sister, Tomi Kuwayama Tedesco, 81, is a retired nutritionist living in Los Angeles. His brother, George, 75, is a retired senior curator of the Los Angeles County Museum.

Wearing his Silver Star Medal on the lapel of his jacket, Kelly said he returned home from the war in Europe thinking he'd be sent to Japan to fight, but instead was discharged on July 29, 1945. He was in Times Square when the Japanese surrendered in August 1945.

It didn't take Kelly long to realize that the wartime attitudes of many Americans hadn't changed. He and other veterans of Japanese ancestry were welcomed home with all kinds of insults, including signs that read: "No Japs Allowed" and "No Japs Wanted." They were denied service in shops and restaurants and their homes were often vandalized or set on fire.

Unable to find a job, Kelly used the GI Bill to attend Harvard University Business School and earned a master's degree in business administration in 1947. He went to work as a statistician for Western Electric Co., but was laid off about two years later.

"My father had met people from Japan who had offices in New York City before the war," Kelly said. "English was prohibited in Japan during the war, so they didn't have anybody who could handle the English language. They offered me a job as a 'local hire,' which meant you couldn't be promoted above a certain level."

In order to be promoted, he would have to work in the head office in Japan and be assigned to the United States. The salary would be $18 per month, the same as employees earned in Japan at a particular rank and class group. The going rate in U.S. companies then was $100 per month.

Kelly agreed to work in Japan for a year, which he termed a "rather interesting experience." Since Japan was occupied and he was hired as Japanese, he couldn't visit the American sector. He lived with a Japanese company official.

"They usually ate rice and fish for breakfast, but they gave me ham and eggs and powdered coffee," he said. "I told them I'd eat the same thing they ate. In the evenings, they used me as an interpreter when they met with Americans and Europeans. They would go to banquets and I'd eat very well. I spent most of my time in Japan writing letters in English to security brokerage houses."

Kelly was promoted to management and reassigned to the United States. After awhile, he realized continued employement might mean returning to Japan.

"I decided to leave and got a job with the Commerce Department's Office of Foreign Direct Investments," he said. "When that program came to an end, I was hired by the Securities and Exchange Commission as an economist."

Kelly retired in 1987 and lives in the nation's capital with his wife, Fumiko, 68, a retired Senate case worker. Today, he divides his time reading, playing golf and working with various organizations, such as the foundation behind the Japanese American Memorial to Patriotism in Washington. His wife keeps busy as a volunteer reader to the blind at the Department of Education, gardening, photography and working on her computer.