- Home

- Artwork and Photography

- Army Artwork

- Prints and Posters

- The American Soldier: Set 4

The American Soldier, 1776

The return of Colonel Henry Knox, Chief of Artillery, to Boston with cannon from Fort Ticonderoga and their subsequent placement on Dorchester Heights made the British position in the city untenable. British General Sir William Howe held a council of war and decided to evacuate Boston. General George Washington agreed not to interfere, and the British sailed on 17 March 1776.

+ Click here to expandWashington surmised the British would next move to occupy the city of New York "For should they get that Town ... they can stop the Intercourse between the northern and southern colonies upon which depends the Safety of America." As a consequence Washington ordered the new Quartermaster General, Thomas Mifflin, to move the American army overland from Boston to Connecticut and arrange to transport troops and "stores, Artillery, Camp Equipage &c" to New York. Mifflin made the necessary arrangements with a number of Connecticut merchants. Since the number of vessels was limited, he told Joshua Huntington, a Norwich merchant, he wanted those ships "which carry the first Detachment ... back to New London as soon as possible & to be got ready for the second Embarkation." For the fledgling Army and the new Quartermaster Corps, the overland move, the embarkation, and the movement by sea were all unqualified successes.

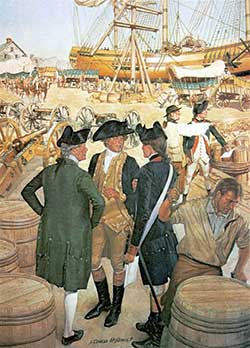

On the docks of New London the second embarkation is underway. John Parke, Assistant Quartermaster General, center, and Ezekiel Cheever, Commissary of Artilery, give instructions to a captatin of artillery whose

company has just arrived from Boston. In the background a civilian contractor points to another pier where the captain will find the ship to transport his men and cannon. The two officers can be identified as members of the Corps of Artillery by the red facings and yellow buttons of their uniforms. Parke wears the uniform of the General Staff, a blue coat with buff facings. On the other hand Cheever, as Commissary, wears civilian dress.

- Click here to close

The American Soldier, 1815

One constant problem in the early years of the Army's existence was the clothing of soldiers. Dependence on imports meant a continual shortage of textiles. Congress occasionally failed to provide clothing funds, and uniforms were not stockpiled but ordered on a yearly basis. The system of procurement and the men empowered to administer it also changed sporadically.

+ Click here to expandIn the years following the War for Independence the problems remained the same but less serious because of the small size of the Regular Army. Although some attempts were made in 1803 to encourage domestic manufacturing of textiles, it took President Thomas Jefferson's Embargo of 1808 to force civilian contractors to turn to domestic woolens and linens. Initially the quality left much to be desired, causing the Superintendent of Military Stores, Callender Irvine, to reject one quarter to one third of the uniforms contracted for.

The outbreak of the War of 1812 and the appointment of Callender Irvine as Commissary General of Purchases led to the introduction of procurement procedures which lasted for many years. Just prior to his appointment and as part of his ultimate goal to have uniforms made "under my own eye," Irvine persuaded the Deputy Commissary General to have cloth purchased by the Army cut at the Philadelphia Arsenal before allocating it to master tailors. He hoped this would eliminate the theft of cloth, insure greater uniformity, and lead to more efficient sizing of uniforms. When Irvine assumed his new post he went further and rented a building in Philadelphia exclusively for cutting and inspecting clothing. Finished articles were sent to the arsenal for distribution.

The sale of waste fabric paid the rent on the building. He next moved to eliminate the master tailors who functioned as contractors. These men, he believed, exploited those working for them and brided inspectors to accept inferior garments. Irvine used three men to cut material. The pieces with the necessary accessories such as buttons and braid were then given directly to seamstresses. In this process he employed three to four thousand people capable of turning out two to three thousand uniforms per week.

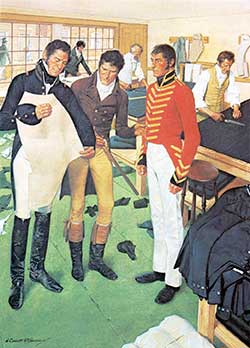

In the Philadelphia building specifically rented for the purpose, three cutters work in the background. Callender Irvine discusses the pattern for the front and sides of the Engineer enlisted men's coat with Francis Brown the head of the cutting establishment. Irvine is wearing the blue general staff, single breasted coat with the embroidered buttonholes allowed general officers on the collar only, and gilt bullet buttons. The man on the right models a coat of the Corps of Engineers enlisted musicians.

- Click here to close

The American Soldier, 1848-1885

In 1833 the Washington National Monument Society, a private organization, declared its intention to follow through on a Congressional resolution, passed after the American victory at Yorktown, authorizing the construction of a statue to honor George Washington. The resolution had not been acted on because Washington objected to the use of public funds for such a project. With a great deal of public support, the organization raised money and in 1848 persuaded Congress to set aside land for a monument. The legislators agreed and authorized a site near the location L'Enfant, the designer of the federal city, had long ago designated for a statue of Washington.

+ Click here to expandThat same year work commenced on the fourth of July with the setting of a 24,000 pound marble cornerstone.

Eleven years later with work still in progress, the Secretary of War received a request from the society for an officer of the Corps of Engineers to direct the construction. Lieutenant J. C. Ives received the assignment which lasted for only one year when, at a height of 156 feet, work came to a halt because of a lack of funds and the impending Civil War.

The society continued in existence and in 1874 asked the Chief of Engineers to inspect the shaft in preparation for resuming work. Two years later Congress approved funding and assumed public ownership of the obelisk. After re-examination of the structure in 1878, a decision was made to strengthen the foundation. Lieutenant Colonel Thomas L. Casey, who had constructed fortifications during the Civil War, took charge of the project. He had fifty-one percent of the old foundation replaced and enlarged from 6,400 to 16,000 square feet. At the same time Casey corrected a deflection in the shaft, a remarkable engineering feat at the time for a structure weighing about 81,000 tons.

On 21 February 1885 at the dedication ceremony workmen placed a solid aluminum capstone on the peak of the obelisk. Ending his speech, Casey addressed President Chester A. Arthur, "For and in behalf of the joint Commission for the completion of the Washington Monument, I deliver to you this column."

At the base of the partially completed monument Lieutenant Colonel Casey discusses details of the construction with one of the civilian contractors. Two junior Engineer officers wait to speak to Casey while one of the laborers employed by the contractor looks on. Both Casey and the two junior officers wear the officer's undress uniform of the period; a dark blue single breasted sack coat with five convex gilt buttons in front and a small falling collar, and plain dark blue trousers. The gold laurel and palm wreath encircling the silver castle on the front of the dark blue forage cap identifies them as Engineers, while their rank is shown by the insignia on their dark blue, general staff shoulder straps.

- Click here to close

The American Soldier, 1881-1883

The 1879 meeting of the International Polar Conference proposed a number of observation stations around the northern polar area to gather scientific information, especially "to elucidate the phenomena of the weather and the magnetic needle." Newly appointed Chief Signal Officer Brig. Gen. William Babcock Hazen decided to use Signal Corps funds for an expedition to Point Barrow, Alaska. A station there would fill the gap between a Russian outpost at the mouth of the Lena River and a Danish station on the west coast of Greenland. The expedition, plus another to an island off Greenland, formed the United States contribution to the International Polar Year of 1881.

+ Click here to expandThe orders establishing the stations included requirements for record keeping; instructions for magnetic, meteorological, and tidal observations; and proposed subjects for photographs, sketches, and topographical maps.

First Lieutenant Patrick Henry Ray of the 8th Infantry received command of the Point Barrow expedition which began its work on 16 September 1881 and for the following two years contributed to the scientific knowledge of the frozen north. In addition to fulfilling the general instructions, the expedition made an attempt to correlate the Aurora Borealis with electrical currents on the surface of the earth. The men gathered many specimens of both flora and fauna, some never before observed. Ethnological research produced a wealth of information on the Point Barrow Eskimos. Although without special training Ray became especially interested in the Eskimos and completed an "ethnographic sketch" of merit. He made two trips exclusively in the company of Eskimos. The first was ostensibly to obtain fresh meat; however, Ray really wanted to see if her could "travel with safety alone with these natives."

As the Aurora Borealis lights the sky, Lieutenant Ray and several Eskimos and their families travel inland. Their cold weather gear is fashioned from animal skins and is typical of the native clothing of the period. The dog sled is two meters long and one meter wide at the rear, tapering to about seventy centimeters at the nose. Over the wooden frame, deerskin is laced with leather thongs. Covering the equipment is a dog-skin rug. The men carry 1873 rifles, .45 caliber.

- Click here to close

The American Soldier, 1886

An 1872 act of Congress created the first national park, Yellowstone. This legislation sought to preserve the beauty of the area "for the benefit and enjoyment of the people" and made the Secretary of the Interior responsible. During the ensuing years the fortunes of the park took many turns, mostly for the worse. A few superintendents attempted to stop the growing vandalism and the destruction of game. Others hired assistants to gain political favors. These "irresponsible imbeciles," so-called by the Governor of Montana, contributed to the vandalism by breaking off pieces of the geyser formations to sell to tourists.

+ Click here to expandAnother superintendent treated the park as his private game preserve and added to the senseless killing of wildlife. A visitor to Yellowstone claimed that in one winter alone 1,500 to 2,000 elk were slaughtered for their skins. Lieutenant General Philip H. Sheridan expressed dismay at the killing and offered to send troops to halt the poaching.

In 1883 Senator George C. Vest added an amendment to a bill which authorized the Secretary of the Interior to request "necessary details of troops" to maintain order in the National Park. When in 1886, after a stormy Congressional debate, funds for the administration of Yellowstone were cut, the Secretary of War received a request for troops.

On 20 August 1886 Captain Moses Harris, Commanding Officer, Troop M, 1st Cavalry, relieved the civilian superintendent. Although military control was to be of short duration, troops remained for 32 years. Slowly order was established. During the tourist season an infantry company guarded the geysers. Because of the vastness of the park, poaching continued to be a problem. Harris formed ski patrols and eventually two troops of cavalry remained at Yellowstone the year round. With limited authority, the Army could only evict captured poachers and confiscate their equipment. Eventually, the latter practice was halted; instead troopers marched intruders out of the park and then placed their equipment on the other side of the Yellowstone.

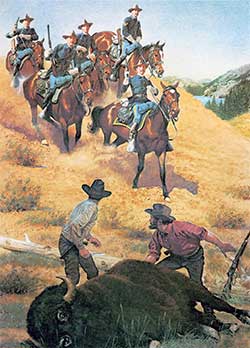

Such a fate awaits these two poachers so engrossed in skinning a buffalo they fail to notice one of Captain Harris' patrols. The enlisted men wear the standard dark blue blouse of navy flannel for fatigue and field service. The lieutenant is wearing the issue five button officer's sack coat with shoulder straps. The yellow chevrons and yellow trousers stripe on the sergeant indicate cavalry. Other than the lack of a carbine and the addition of a dress saddle blanket, the officer carries the same field gear as the men. The enlisted men carry the 1873 carbine, .45 caliber, and the 1872 revolver, .45 caliber.

- Click here to close

The American Soldier, 1906

One of the greatest natural disasters in United States history, the San Francisco Earthquake, occurred on 18 April 1906 at about 5:15 a.m. The shift in the San Andreas fault toppled numerous chimneys, severely damaged others, and opened gaping cracks in the cobblestone streets. But the havoc wrought by the trembling earth was only the beginning. Almost immediately fires, fueled by debris and gas escaping from broken lines, sprang up in various sections of the city. Unfortunately, the quake also damaged water mains and to halt the spreading fires city officials decided to dynamite buildings to create fire lanes.

+ Click here to expandThe city fire chief sent an urgent request to the Presidio, an Army post on the edge of the stricken city, for dynamite. Brigadier General Frederick Funston, commanding the Department of California and a resident of San Francisco had already decided the situation required the use of troops. Collaring a policeman he sent word to the Mayor of his decision to assist. Martial law was never declared, however, and troops took guidance from civilian authorities.

During the first few days soldiers provided valuable services patrolling streets to discourage looting and guarding buildings such as the U.S. Mint, post office, and county jail. They aided the fire department in dynamiting to demolish buildings in the path of the fires. The Army also became responsible for feeding, sheltering, and clothing the tens of thousands of displaced residents of the city. This support prompted many citizens to exclaim, "Thank God for the soldiers!" Under the command of Maj. Gen. Adolphus Greely, Commanding Officer, Pacific Division, Funston's superior, over 4,000 troops saw service during the emergency. On 1 July 1906 civil authorities assumed responsibility for relief efforts and the Army withdrew from the city.

As fires rage through San Francisco soldiers, dressed in olive drab service dress with strapped leggings and wearing campaign hats with light blue cords designating infantry, unload one of many civilian wagons pressed into service with their drivers. (In addition to supplies from Army depots, food, including much flour, came from cities all over the United States.) The officer with the black visored service cap is a lieutenant colonel of infantry. With his olive drab, single breasted sack coat, with four chokedbellow pockets, low falling collar and dull finish bronze metal buttons he wears olive drab service breeches and russet leather boots. The officer and the artillery sergeant known by his scarlet hat cord carry .38 caliber service revolvers; the rifles shown are the new .30 caliber 1901 "Springfields."

- Click here to close

The American Soldier, 1908

Considering the Army's dependence on horses and mules for transportation in the nineteenth century, it is surprising how little attention was paid to insure an adequate supply of remounts. The outbreak of the Civil War and the accompanying demand for many animals showed a need for centralized procurement. By the end of the conflict, the Quartermaster General's Office was obtaining draft horses and mules while the Cavalry Bureau secured riding horses. To insure that remounts remained in good condition, the transfer of men and even entire units from the cavalry to the infantry was allowed if inspectors found evidence of animal abuse or neglect.

+ Click here to expandAfter the struggle ended, the earlier indifference toward remounts again prevailed until Maj. Gen. James B. Aleshire, Quartermaster General, recommended a separate office solely responsible for procurement and issue of horses and mules. He also urged the establishment of regional remount depots. Congress responded and passed an act in 1908 authorizing a system of remount depots. General Order 59, April 1908, created the first depot at abandoned Fort Reno, Oklahoma. Established in 1875, the post once protected the Cheyenne and Arapaho Agencies and cattle herds on the Old Chisholm Trail.

Captain Letcher H. Hardeman of the 10th Cavalry took command of the depot, and 1st Lt. William P. Ennis, 1st Field Artillery, joined him as second in command. Civilian cowboys, farm hands, and former soldiers purchased, trained, and issued the animals. Hardeman received specific instructions to see "that the horses were well fed and cared for, gently and kindly handled at all times, and properly exercised and broken."

Captain Hardeman, astride a horse in his care, puts the animal through its paces for visiting officers and a noncommissioned officer from one of the Army's cavalry regiments. They are only a few of the many horsemen who inspected the new remount depot which one visitor described as "a source of wonder and glad surprise to everybody in our army." The officers wear the khaki service uniform with bronze insignia. They have service caps while Hardeman and the sergeant wear the 1882 campaign hat. The inspecting officer on the far left is shod in boots purchased privately (issue boots were wider at the calf), and the sergeant and the other officers wear the recently approved russet-leather leggings. Two civilian cowboy trainers are in the background.

- Click here to close

The American Soldier, 1944

After the breakout from Normandy, the rapid advance severely strained the supply system. The crossing of the Seine further complicated matters and a critical stage was reached when an impending operation required stockpiling 100,000 tons of supplies. As only 25,000 tons could be moved from the beaches by rail, trucks would have to deliver the balance to points behind the front lines. The assignment fell to Advance Section, Communications Zone. The Motor Transport Services provided direction and coordination while the Motor Transport Brigade handled the actual movement of vehicles. The plans took into account the narrow roads of provincial France and called for a one way loop from St. Lo to supply dumps east of the Seine.

+ Click here to expandLoaded trucks used a northern route and empty vehicles returned along southern roads. [Red balls on the trucks identified the vehicles and on sign posts, the roads} while military police on the route sported distinctive red balls on their helmets. Because of this unique identification the operation became known as the Red Ball Express.

Red Ball convoys began to roll on 25 August 1944. After four days tonnage reached a peak of 12,342 tons carried by 5,958 vehicles from 132 truck companies. In addition to regulating convoy movements, traffic control points at main intersections provided services for both drivers and vehicles. At midpoint on the route drivers were relieved by rested men. They waited and picked up the same truck on the return trip. With only two drivers, a truck was more likely to receive proper maintenance.

By 16 November the Red Ball Express had reached the end of its usefulness; the route stretched over 600 miles and men and vehicles had arrived at the limits of their endurance. Fortunately repairs to rail and waterways made it possible to continue the flow of supplies to the front. During its 81 days of operation the Red Ball Express handled 412, 193 tons. Expecting all Allied pause for resupply, the Germans were caught off guard. As a consequence many lives were saved and the conflict brought closer to a victorious conclusion.

Here in a soggy field somewhere outside Versailles, a driver has pulled his disabled truck out of a convoy. Determined nonrepairable by a Red Ball maintenance crew, its cargo is transferred to a replacement vehicle. When this is finished the driver will take a position in another convoy and eventually rejoin his unit at the exchange point in Normandy. The maintenance crew and driver are dressed in winter field uniform consisting of wool "OD" (olive drab) trousers and heavy twill field jackets. All are armed with 1911A1, .45 caliber, semiautomatic pistols.

- Click here to close

The American Soldier, 1954-1976

The Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC), established by Congress on 14 May 1942, was retitled the Women's Army Corps (WAC) and made a component of the Army of the United States one year later. Not until 1948 and passage of the Women's Armed Services Integration Act, however, were women included in the Regular Army and the Reserve; and still later-1967-they finally received equal promotion and retirement status with men.

+ Click here to expandA noncombat branch of the Army, the WAC needed a place to train both enlisted and commissioned women. On 14 June 1948 Camp Lee, Virginia, became the official site of the WAC Training Center; on 25 September 1952, the WAC School was also established at (then) Fort Lee. Two years later (July 1954), Fort McClellan, Alabama, became the new home of the Women's Army Corps Center and the Women's Army Corps School. Built specifically for women, the center and school could accommodate 2,400 women from basic training through officers' advanced course. The center also had an all-female military band, the 14th U.S. Army Band, whose history dates back to 21 January 1944. Every woman entering the WAC passed through the gates of Fort McClellan until October 1973 when expansion under the all-volunteer concept required activation of two more women's basic training battalions at Fort Jackson, South Carolina. As costs rose and the need to economize brought gradual consolidation of training and appointment of WAC officers in the other noncombatant branches of the Army, the WAC School was discontinued. WAC basic training battalions became part of formerly all-male training brigades, and separate training brigades for WAC's faded away in 1977.

Atop one of the hills at Fort McClellan, so familiar to the WAC's who trained there between 1954 and today, stands a large flagpole that overlooks the brigade parade ground and training area where women recruits still March, live, and train in separate companies. If one were to ask a woman who trained here to name one of her most vivid memories she would probably say, "the retreat ceremony." To the basic trainees, it was a special honor to be chosen a member of the detail that raised and lowered the flag on the hill. Everyone sensed their pride, for their steps were never firmer nor their backs straighter than when they marched to and from the flagpole with their platoon sergeant.

The trainees shown here, dressed in the green-cord summer uniform and dress hat, carefully gather in the huge 20 by 38 foot garrison flag, used on national holidays and special occasions, as it is lowered at a retreat ceremony to the boom of the cannon at post headquarters and the strains of the national anthem played by the 14th U.S. Army Band nearby. The faces of the young women with the flag show their special concern lest a single thread touch the ground. High winds and rain sometimes made it a major task for a platoon to maintain its grasp on the outsized banner. The women in formation in the background, soon to be needed to extend and then fold the flag, salute with pride but are alert to assist if necessary.

For members of the Women's Army Corps, wherever and whenever they serve, a flag ceremony, especially a WAC retreat ceremony, is a special moment that never fails to bring forth some unashamed tears as emotions are stirred by the slowly lowered flag and the music of their special band.

- Click here to close

The American Soldier, 1975

Army Nurse Corps members in clinical specialties from psychiatric and mental health to pediatrics and medical-surgical provide in-patient care at medical treatment facilities worldwide. Advanced training in many special aspects of nursing is available at larger US Army medical facilities. This training is vital in maintaining readiness to fulfill requirements placed on the Army Nurse Corps in peace and war.

+ Click here to expandThe Army Nurse Corps comes to the attention of the general public when its members provide patient care during international relief operations. These assignments are unique to the Nurse Corps because civilian nurses do not accompany emergency relief operations overseas. When the United States aids a stricken nation, Army Nurses provide direct patient care.

Operation New Life occurred during the spring and summer of 1975. With the collapse of South Vietnam, more than 130,000 Southeast Asian refugees were evacuated to the United States. Over 90,000 received some type of medical care provided by Army nurses who helped staff facilities at stations of the trip.

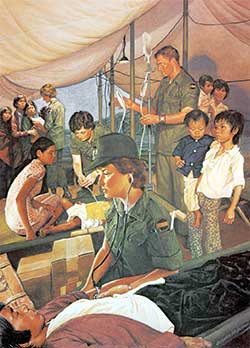

In the foreground, as concerned relatives look on, an Army nurse checks an injured Vietnamese. The scene is typical of many long evenings in tents set up as emergency medical stations on Guam, the first stop for the refugees. The nurses are dressed in two-piece tropical combat uniforms of olive-green, rip-stop cotton poplin. The male medical orderly setting up the plasma bottle also wears a two-piece olive green uniform of cotton poplin.

- Click here to close

<< back to Prints and Posters Series