CHAPTER SIX

MODERN BORDER OPERATIONS

1970 - 1983

(U) A German Federal Border Guard patrol company observations with a 2d Armored Cavalry Regiment border patrol. March 1983.

(U) Members of the German customs Police (Zoll) and their everpresent dog sometimes guided US border patrols. March 1983.

(U) Members of the 2d Armored Cavalry Regiment and the Bavarian Border Police surveil the border near Amberg. March 1983.

(U) A German Federal Border Guard aircrew consult with a 2d Armored Cavalry Regiment border patrol. March 1983.

(U) Resolution of the "German Question," Temporarily

(U) Ever since the founding of the modern German nation in 1871, scholars and diplomats have asked, "What is Germany? What are her borders?" The onslaught of the Cold War has not aided the Germans or the rest of Europe in resolving these questions. Both Germanys chose sides -- or were forced to choose sides -- and were incorporated into their respective alliance systems, thus closing the door on reunification in the post-war era. In the mid-1950s, the German Democratic Republic dropped its reunification slogans and from then on spoke only of a confederation of the two states, while the Federal Republic stated the "Hallstein Doctrine" in 1955, which considered recognition of the German Democratic Republic an "unfriendly act." By the end of the 1960s, when it became obvious the "German question" was not going to be resolved by reunification in the foreseeable future, there arose a feeling that more normal relations between the two Germanys were long overdue. This formidable task was tackled in 1969 by the Federal Republic's new Chancellor, Willy Brandt, with his Ostpolitik. The next two years were a fertile period, with a series of treaties being concluded between the Federal Republic and its eastern neighbors, and between the Four Powers on the question of Berlin.1

(U) The Federal Republic and the Soviet Union signed a treaty in 1970 in which the two sides renounced the threat or use of force and undertook to settle their disputes exclusively by peaceful means. Of interest to this study, both agreed that borders as they existed in Europe were inviolable. In a "Letter on German Unity," handed to the Soviets at the signing ceremony in Moscow, the Federal Republic declared, "that this treaty does not conflict with the political objective of the Federal Republic of Germany to work for a state of peace in Europe in which the German nation will recover its unity in free self-determination."2

(U) In December 1970 a treaty was signed by the Federal Republic and Poland that laid the foundation for full normalization of relations between the two countries. Among its provisions was a recognition of the western frontier of Poland as being the boundary line along the Oder and western Neisse Rivers, thus resolving a long-standing territorial dispute between Poland- and the former German nation. The German Democratic Republic had recognized this border in 1950. A treaty normalizing relations with Czechoslovakia was signed in 1973, a year which also saw diplomatic relations being resumed with Bulgaria and Hungary.3

GSM 5-1-84

[175]

(U) The 1970 treaties with the Soviet Union and Poland paved the way for negotiations between the former Allies on the status of Berlin. The United States had been reluctant to enter into serious negotiations with the Soviet Union because it did not think the Soviets were serious about solving the continuing sore point of guaranteeing access to Berlin. However, the two treaties indicated the East Bloc was serious about improving relations, and NATO speculation centered on the theory that settling the Berlin question was a necessary prelude to accomplishing an overall Soviet diplomatic goal of receiving international recognition of the split of Europe and Soviet hegemony over the Eastern half. In addition, the Soviets had become involved in a border war with the Chinese two years prior to the negotiations, which -- in combination with President Nixon's intent to play the "China card" -- led the Soviets to seek a policy of détente with the West. A solution to the Berlin question would have to precede a general policy of relaxation of tensions in Europe. The Four Powers began serious negotiations on Berlin in March 1970 and the Four Power or Quadripartite Agreement was signed on 3 September 1971. When the agreement went into effect on 3 June 1972, the Four Powers had seemingly established a new status for the former German capital, primarily by Soviet acceptance of the presence of its former allies in Berlin. Although it brought no final solution to the Berlin question -- the signatories could not even agree upon its geographical area of application -- the agreement did contain regulations that eased the continued joint occupation of Berlin. Significantly, it decreased problems Allied traffic had in crossing the Inner German Border and transiting to Berlin. There were still periodic frictions over interpretations of the new regulations, but basically the Berlin question remained quiet thereafter.4

(U) By far the most significant treaty of this period was concluded on 21 December 1972, when the two Germanys signed the "Treaty on the Basis of Relations between the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic." The treaty called for a renunciation of force, a recognition of the sovereignty of the two states, an exchange of "permanent missions," and the membership of both states in the United Nations. Although it was a de facto recognition that German reunification was a dead issue for the time being, the Federal Republic handed the German Democratic Republic a letter restating its basic policy that it retained the objective of endeavoring to obtain a state of peace in Europe that would enable the German people to regain unity by application of the right of free self-determination. The Federal Republic continued to consider the German Democratic Republic a part of the "German nation," not as a foreign country, which

GSM 5-1-84

[176]

resulted in numerous fictions in its relations with its neighbor.

Beginning in 1974, however, the German Democratic Republic ceased referring to the "German nation" in its constitution and insisted the two "states" were now two separate "nations."5

(U) One tangible benefit of this new cooperation between the two German states was the establishment in 1972 of the Grenzekommission (Border Commission), which was composed of representatives from both states and had a charter to resolve border problems. When the commission began meeting in 1973, one of its first tasks was to establish exactly where the border was. In a number of places, the occupation forces had altered the frontiers specified by the London Protocol, which itself had followed old, somewhat imprecise, provincial borders. Documents had to be dug out of archives, a joint survey conducted, new marker posts set up, and border stones replaced. In February 1974 the commission began surveying the demarcation line in order to accurately place new border markers. Survey teams composed of members from both states faced occasional difficulties because of their slightly different survey methods, but generally were successful in resolving their differences. The new border markers were plain-white granite stones with the initials DDR placed on the east side. Most of the surveying and stone laying were completed by the end of 1975. By the end of 1983, the only section of the border that remained unfixed was along 80 kilometers of the Elbe River between Lauenburg and Bleckede. Both sides had agreed to shelve the question for the time being since no solution was in sight. The commission usually met about eight times a year, alternating between East and West German locations, and was generally rated a success. In a spirit of compromise, it thrashed out many practical problems that could have become political problems; however, it deliberately kept aloof from most of the life-and-death questions on the border. For instance, it did not discuss escapes or questions of compensation for injuries received during border incidents.6

(U) One interesting example was the maintenance of a Central Data Registration Agency at Salzgitter, which since 1961 had been meticulously keeping track of crimes committed by East German judges, border guards, and jailers that, theoretically, would result in a day of reckoning if the two Germanys were ever reunited. Since the Federal Republic considered East Germans citizens of the German nation, it held these officials would be accountable under its Basic Law. (The Stars and Stripes [Eur ed.], 14 April 1984, p. 18. UNCLAS.)

GSM 5-1-84

[177]

(U) Unfortunately, the "German question" had not been resolved by the beginning of the 1980s. Détente had begun to unravel in the latter part of the 1970s when a series of events led both sides to take stock of the situation and become more tough minded toward each other. The NATO allies decided that a. response was required to the large scale build up of Soviet SS-20 missiles aimed at European cities and military forces. The result was the so-called "two-track decision," agreed to at a NATO meeting in Brussels on 12 December 1979, in which the NATO partners called for the conduct of serious arms-control negotiations with the Soviet Union or, failing their satisfactory conclusion, a modernization of NATO's forces to include new US intermediate-range missiles (Pershing II and cruise missiles). Rather than seriously negotiate an arms-control treaty, the Soviets fanned the passions of pacifist groups in the West -- particularly in the Federal Republic and -the Netherlands -- with rhetoric on how the West was escalating the arms race by matching the Soviet build up. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979 and the suppression of Polish labor unions by the Polish military in September 1981 convinced many that the Cold War had resumed and détente was dead. Interestingly enough, the two Germanys seemed intent upon not letting heightened East-West tensions affect their increasingly intertwined political and economic relations. The period since the conclusion of the Treaty on the Basis of Relations had seen a tremendous growth in trade as well as social interaction between citizens of the two states, and both sides wished to continue these mutually beneficial relations. In 1983, for instance, in spite of the shrill East-West rhetoric, the two Germanys inaugurated new trade pacts and business loans, and tried to reduce tensions along the Inner-German Border by easing emigration restrictions on East Germans wishing to leave the German Democratic Republic and by the removal of mines on the East German border barriers (see below, The Inner-German Border). Whether these efforts would succeed could not a determined as this study came to a close.7

(U) The inner-German border, after the work of the Grenzekommission was essentially completed in 1975 (see above), was identifiable from both the ground and the air for those familiar with its complex series of border area markings and structures. The actual border was marked with plain white granite border trace or survey stones. In addition there were historic border marking stones of Saxony, Hesse, and Prussia that may or may not have marked the border accurately, depending upon the circumstances of each stone or subse-

GSM 5-1-84

[178]

(U) German Democratic Republic border marker.

[179]

quent agreements. Almost immediately on the border or right next to it, the Federal Government had erected signs that stated: "Halt! Hier Grenze." Interspersed between these signs were tall white poles with red tops or blue stripes that aided in determining the border in periods of high snow banks. In the 1960s the East Germans had erected, a few meters to the other side of the border, 1.5-meter tall poles painted with black, red, and gold stripes and a DDR emblem inserted near the top.

To insure that US personnel did not inadvertently cross the border, US military authorities established two restricted zones next to the border:

- There was a 50-meter warning zone for all US forces personnel marked with a sign that stated: "Attention. 50 meters to the border."

- There was also a 1-kilometer restricted zone for all US forces personnel, other than those authorized to operate in the border area or who had received special permission to be in this sensitive area. These signs were placed next to all traveled roads and stated: "US Forces Personnel. HALT. 1 Kilometer to Czechoslovakia ["Soviet Zone" or after 1974 "German Democratic Republic," signs varied defending upon period or location]. Do not proceed without authority. (For examples, see FIGURES 5 and 6 in Chapter 5.)

(U) In addition to the official border markers, the inner German border was roughly marked by an extensive barrier system that had been erected to restrain illegal emigration to the West. The fences and other structures were normally located from two meters to two kilometers east of the true border.

Although the Soviets had begun building the first serious barrier system along the inner German border as early as 1952, it had always been militarily ineffective and was designed more to keep people in rather than invading armies out. NATO planners, as a point of interest, viewed the more sophisticated barrier system of modern times as militarily in their interest in that it would have to be breached by Warsaw Pact forces if they decided to invade the West and would slow down or funnel incoming forces as they crossed the border. Up until the late 1960s the most common type of barrier had been a triple-strand barbed wire fence on wooden posts, augmented with other security devices such as land mines. However, these barriers had proven ineffective and had not stopped determined escapees. The East Germans decided in 1967 to begin construction of a "modern" border

GSM 5-1-84

[180]

barrier system, with construction on the new system beginning in September 1967 and initially programmed to be completed in 1970. This initial effort actually carried over into 1972, when the East Germans began to build an even more sophisticated system that was still being constructed in a few locations up into the 1980s.

The original plan called for replacing the barbed wire fencing with wire mesh or "cyclone" style fencing, paving the vehicle track to permit year-round motorized patrolling, constructing anti-vehicle ditches, and building new bunkers that would blend in with the terrain. The East Germans hoped to construct a system that would reduce the number of personnel required to guard the border while changing the look of the border to decrease its negative psychological impact on Western visitors. Primarily, they wanted to upgrade their capability to detect and apprehend would-be escapees further from the border. The new system was very successful in decreasing the number of escapees. In the latter part of the 1960s an average of more than 500 escapees made it safely across the border each year, but as the interim barrier system neared completion in the first half of 1970, only 25 illegal border crossers managed to get across safely.8

The border barrier system, as it existed in the early 1970s, had elements of both the old fencing and the new, more complex barrier system (see FIGURE 7). Essentially, it was designed to control the five kilometers next to the border by a series of different kinds of barriers as well as defensive and detection devices. Right next to the border was the old 3-strand barbed wire fencing stretched on wooden posts approximately 2 meters high and 15 meters apart. Starting in 1964, the East Germans had begun replacing the older fences with newer ones using concrete posts, often doubling them with a distance of between 2 to 10 meters separating the 2 rows. In some areas they had placed rolls of concertina wire between the fences. As they built these newer fences they usually tore down the old ones. It was during this period they had begun the trend of building fences further from the border, in some instances up to 500 meters back.

Next to this initial fence or fences was a 10-meter wide death strip in which East Germans were not allowed unless they were working on the fences and accompanied by guards. Although the guards in the past had attempted to apprehend the escapees in this strip and fired only as a last resort, by the end of the 1960s there was a loosening of the rules of engagement, and they were beginning to shoot without warning anyone caught in this area. This area was allowed to deteriorate after the newer fences were built, especially as the older fencing was torn down.

GSM 5-1-84

[181]

FIGURE 7

Source: USAREUR Special Intelligence Study, 15 May 1971, subj: The V U.S. Corps Border Study, p. 39. CONF. XGDS.

[182]

As the program progressed in the 1967 period, the East Germans began building double fences further from the border, -usually 20-30 meters back -- out of either barbed wire on concrete posts or with the newer metal mesh fencing. By this period, in addition to the above mentioned fencing they were also building 3-meter high corrugated metal fences or concrete slab fences -- the latter two being built in high risk areas. In addition to placing rolls of concertina wire at the base of these fences, they usually placed mine fields between the double rows. The older mine fields had contained wood-encased PMD-6 anti-personnel mines, but they were being replaced inside the newer fencing by plastic-encased PMN-6 mines, which were more weather resistant. Finally, the inner fence sometimes was an electrified signal fence that when triggered would activate a light in the watch towers indicating the location of the escape attempt. They also employed trip wires that would set off blank cartridges or flares in this area.

Various types of anti-vehicle ditches had been constructed along the border in previous years, but during the modernization period there was an extensive increase in these defenses. In the new system they were built right behind the double-fence barrier and were designed to keep vehicles from crashing through the fences. Rather than being constructed to prevent vehicles from crossing the border from West to East, they served to prevent escapes from East to West by car or truck.

Immediately behind the anti-vehicle ditches or up against the inner fence, depending upon the circumstances, a 6-meter "control" strip was built. Like the old 10-meter death strip; this area was freshly plowed and checked frequently for footprints. Beyond this was an area of approximately 90-100 meters that was stripped of all vegetation and served as a firelane. Next to the firelane was a continuous paved convoy or patrol road for all-weather motorized patrols. In certain high risk areas they would set up a 30- to 100-meter long guide line on which one to three guard dogs were attached.

There were two kinds of bunkers normally used along the inner German border: conventional wooden bunkers sunk partially into the ground and having one or more slits facing West Germany; and prefabricated concrete bunkers, generally painted green and brown in a camouflage design, and having observation slits on all four sides. There remained a collection of older bunkers made of cement or concrete, stone masonry, earth, red brick, and other unknown construction materials, but by the early 1970s the wooden and prefabricated concrete bunkers were the most predominant.

GSM 5-1-84,

[183]

FIGURE 8

Source: 1971 V Corps Border Study, p. 56. CONF. XGDS.

[184]

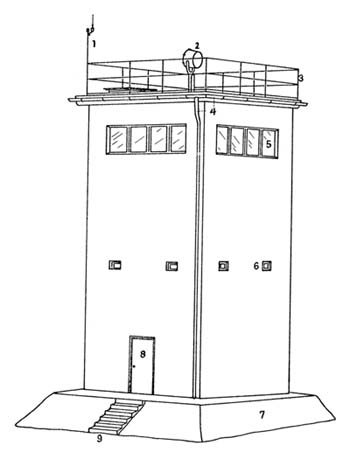

There were four basic kinds of observation towers along the border: 8-meter high wooden towers equipped with a green-roofed observation hut; observation platforms built into trees (rarely manned); wooden trigonometric towers with a boardwalk circling the tower; and the newer prefabricated concrete towers. (See FIGURE 8.) The 8-meter high wooden towers had been the most common in past, but were being replaced or supplemented by the prefabricated concrete towers.9

Prior to 1972, the East German border barrier modernization program had been viewed primarily as a strengthening and upgrading of weak areas of their old system. (See FIGURE 9.) Although elements of a new system had been going up since the program began in 1967, it was in the summer of 1972 that the East Germans seemed to shift gears and began incorporating improvements of the modernization program all along the inner German border. There were two notable improvements in the expanded program: they were replacing most of the barbed wire fences with the 3-meter high metal grid fences, which looked less brutal than the barbed wire, but actually were more effective; and they began installing the new SM-70 antipersonnel mines on the metal grid fences. The SM-70 mines were a particularly lethal deterrent to border crossers and eventually became the mainstay in the East German barrier system. An observer who came upon a deer killed by an SM-70 reported that "an approximately 5 meter area appeared as if it had been worked over by a rake." The SM-70 was a self-firing device that consisted of a small, funnel-shaped barrel resembling a shaped charge, a trigger mechanism with trip wire, electrical connections, a detonator, and a mounting bracket holding two quick or guide wires. Each pair of guide or "bird" wires protected a trip wire, which was electrified by a distributor box on the ground (see FIGURE 10). Subsequently, a plastic housing was added to protect the SM-70 from the elements and attempts to disarm it by illegal border crossers. When detonated, a charge of 110 grams of TNT propelled approximately 80 steel pellets from the barrel, which had a killing radius of approximately 25 meters. They were installed at three levels on the fence poles, aimed parallel to the fence at the top, middle, arid bottom of every other pole. Each line of devices had two guide wires and a trip wire, for a total of nine wires along the fence. Normally, 120 mines were installed on each kilometer of fence.10

(U) An important change to the East German border barrier system occurred in 1973 when the restricted zone was reduced from five kilometers to 500 meters. However, they still patrolled the 5-kilometer zone, which was referred to as a restricted access zone. The new 500-

GSM 5-1-84

[185]

FIGURE 9

Source: V Corps Anl Hist Sum, 1973. Info used UNCLAS.

[186]

FIGURE 10

[187]

(U) In the early 1970s, the barbed wire fences along the inner-German boundary were replaced by wire mesh fences.

[188]

meter restricted zone was marked by a "hinterland" fence, which was a 2-meter high metal grid fence that had electrical signaling devices installed in order to detect attempts at circumvention. This meant that an illegal border crosser now had to cross the hinterland fence and 500-meter restricted zone undetected and then attempt to cross the double border fences and their mines unharmed -- not a very likely happening for those unfamiliar with the system. Another improvement in 1973 was the start of the installation of a border-length communications network, which consisted of a land-line utilizing telephone poles along the paved strip. By the end of 1973, approximately 80 kilometers of the modernized barrier system had been completed on the inner German border adjacent to the US area of responsibility, and the entire system was expected to be completed by 1975. 'However, by the end of 1974, only 200 kilometers had been completed in the US section -- even less had the SM-70s installed -- and by 1975 it was clear that the upgrading of the barrier system would be ongoing for some time.11

By 1976 the East Germans were so confident of their modernized barrier system that as they completed construction of the new double border fences and installation of the pew SM-70 mines, they began clearing the mine fields between the double border fence. However, they began having weather-related difficulties with the electrical circuits of the SM-70s and they began re-emplacing antipersonnel mines between the double fences. The new mines were designated as the PMP-71 and emplaced in three separate rows. They were constructed of plastic, were trip detonated, and were almost impossible to detect with mine detectors. Apparently, these new mines were never widely used, as subsequent intelligence descriptions of the border do not refer to them and list the PMD-6s and PMN-6s instead.

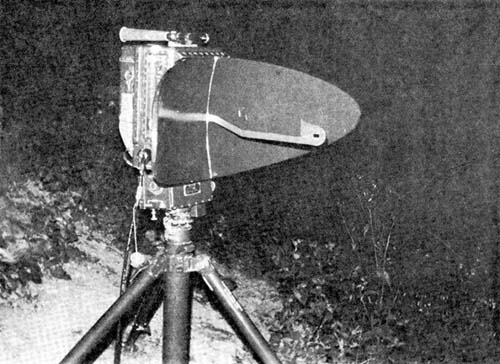

During the same year a special US project, TORCH EYE, determined that the East Bloc guards were using electro-optical devices for night surveillance. This included the following equipment:

- Infrared searchlights were installed on guard towers.

- Helicopters appeared to have infrared night beacons for ease of identification during night operations.

- It was thought the helicopter pilots wore night vision goggles during multi-helicopter operations to avoid collisions.

- Infrared searchlights were mounted on border patrol vehicles and were routinely used for surveillance. By 1980 it was confirmed the

GSM 5-1-84

[189]

|

1. Antenna for R-109 ,c transceiver. (2m high; one at top of platoon CP towers; three or four on Regt main CP tower) 2. Searchlight (1m diameter, 3000 watts, controllable from inside and outside of tower) 3. Railing (1.2m high, constructed of metal pipe) 4. Gutters 5. Embrasures (50cm X 80cm, 4 on each side) 6. Air vents (10cm2, 2 on each side) 7. Earthen mound 8. Door (1m X 2m, opens from inside only, always faces away from border) 9. Stairway (prefabricated concrete, 1m wide., 25 cm deep, 20em high, no railing) |

|

(U) Memory sketch of new command post tower.

(not to scale)

[190]

patrols were equipped with field glasses which could identify infrared sources.12

By the mid-1970s there were reports that some of the round prefabricated concrete watchtowers were collapsing and the East Germans began building new square prefabricated concrete watchtowers (see FIGURE 11).13

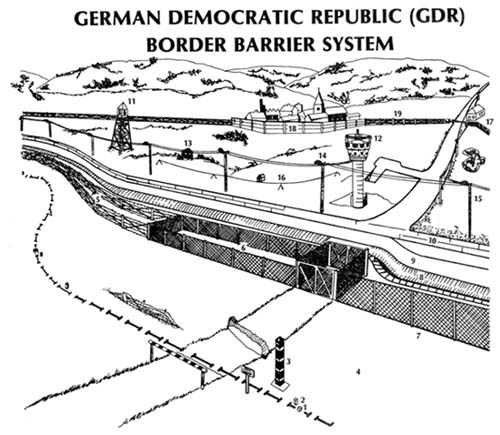

By 1983 the East Germans had worked out many of the technical problems of their modernized border barrier system and seemed to be settling in once again to a gradual strengthening of the system rather than making any radical changes. The addition of the plastic case to the SM-70 apparently solved the electrical circuit problems and they had begun once again to clear the mines in the strip between the double fences. It would be useful to summarize the status of they modernization program along the 1,381-kilometer inner-German border. Approximately 1,289 kilometers of the border had the new metal grid or mesh fence, or in some instances a 3-meter high concrete wall. The latter was used to screen villages, towns, or military installations and was similar to the Berlin Wall. Some 67 kilometers, or 5 percent of the border, still had the old double row of barbed wire fences. The SM-70s had been deployed along 412 kilometers or 30 percent of the border since their introduction in 1972, and if they were installed at the current rate would cover the entire border by the year 2000. However, it was unlikely they would be installed all along the border due to their high cost. There were still 212 kilometers of minefields utilizing the older mines. To complement these obstacles they had 836 shelters of various types, 670 concrete watchtowers, 112 observation platforms, and 84 kilometers of cable runs for some 1,105 border watch dogs. In addition, the border communications network had been strung along the entire border; most of it was underground. Border patrol leaders carried a telephone receiver with plug-in jacks which allowed them to connect into communications terminals erected at short intervals along the entire network. Rivers and lakes were watched by an estimated 24 patrol boats. (See FIGURE 12 for a pictorial description of the current border barrier system.14

(U) It is interesting to note that there were at least three "official" descriptions of the length of the inner-German border; the US military forces described it as being 1,345.9 kilometers long, the British forces as 1,393 kilometers, and the Federal Republic as 1,381. For no better reason than that Germans ought to know the distance of their own inner-German border, the 1,381 kilometer distance was used.

GSM 5-1-84

[191]

GERMAN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC (GDR) BORDER BARRIER SYSTEM

1. Border Trace w/border stones

2. Border Stones

3. Border Column

4. Control Strip, clear up to 100m wide

5. Double-Row Barbed Wire Fence (w/anti-personnel mines between rows)

6. Double-Row Metal Grid Fence (ca 2.5m high w/antipersonnel mines between rows)

7. Single-Row Metal Grid Fence (ca 3m high, may have SM-70 AP mines)

8. Anti-Vehicle Ditch (reinforced w/concrete slabs)

9. Six-Meter Control Strip (freshly graded)

10. Vehicle Patrol Strip (concrete or asphalt)

11: Wooden Observation Tower

12. Round or Square Concrete Observation Tower

13. Concrete Bunker

14. Arc Lamp Zone

15. Border Communications Network

16. Dog Run, w/shelter

17. Traffic Control Point

18. Concrete Wall/Blind (ca 3m high)

19. Hinterland Fence, or Electrical Warning Fence (visual and acoustical

warning devices)

NOT SHOWN: Earth Bunkers, Listening Posts, and Road Barriers

[192]

FIGURE 12

[193]

(U) One other interesting feature of the border barrier system was reported in the Western press in 1983. The East Germans had built at least four tunnels under the barrier system that emerged on their side of the border, which allowed them to surreptitiously insert reconnaissance patrols and agents into West Germany. The West German Interior Ministry reported that at least eight East German border patrols had been identified on the West German side of the border during 1983. The patrols, composed of officers known for their reliability and loyalty to the East German regime, observed troop movements on the West German side and tried to overhear conversations between the various elements of the border patrol forces.15

(U) The SM-70 mines had always been particularly loathsome in the West German public's mind because of their impersonal manner of maiming and killing would-be escapees. There had been several incidents in the past of West Germans setting off the mines with rocks and other missiles as a form of protesting their brutality. An interesting incident occurred in August 1983 when three men set off one of the SM-70s and then through the hole in the fence created by the detonation managed to steal the mine and escape before the East or West German border patrols could arrive at the scene.16

(U) The interest both Germanys had in maintaining stabilized relations during the period of increased East-West tensions in the early 1980s (see above) had a direct impact on the East German border barrier system. When the West Germans granted one billion Deutsche Marks in economic loans to the East Germans in the summer of 19$3, apparently one of the conditions was the dismantlement of the SM-70s along the border. This was particularly significant in that many of the areas that were still protected by double fences with mine fields buried in between had recently been replaced by single higher metal grid fences protected by the SM-70s. In effect, the SM-70 had become the predominant defense in the vast majority of the areas deemed susceptible to illegal border crossings.

(U) When the announcement was first made in September 1983 that the SM-70s would be removed, it was not immediately clear how fast or how -many of the estimated 60,000 SM-70s would be dismantled. West German border agencies were skeptical, and reminded the press that there had been initial euphoria when the East Germans started removing the mine fields between the double fences in the early 1970s only to discover later that they were being replaced by the SM-70s. Subsequent events would validate these early reservations. Although the East German communist leader, Erich Honecker, declared in October 1983

GSM 5-1-84

[194]

that all of the SM-70s on the border fences would be dismantled (while declining to comment on the possibility of their being replaced in a new modernization program), there were indications early on that they were being replaced by newer model anti-personnel mines (SM-701) on the hinterland fence -- thus removing them 500 meters from the border but making them no less effective. Actually, this change in location would probably discourage would-be West German vandals from setting mines off, since they would have to penetrate the border by more than 500 meters, greatly increasing their chances of being apprehended or shot by the East German border guards. Regardless of whether this was simply another step in the "modernization" of the border barrier system or a real decrease in border defenses, the fact remained that the East Germans were removing the SM-70s at a very slow pace, and it was still a hazardous business to attempt to cross the inner-German border illegally.17

(U) The Federal Republic-Czechoslovak Border

The 365-kilometer Federal Republic-Czechoslovak common border was marked by historical border markers and after the mid-1970s, by the same kind of 1-foot square, plain-white granite border trace stones and tall white poles with blue stripes that were used on the inner German border. Although the Czechoslovak Border Guards (Phonranicni Straz - PS) did not have as elaborate a border barrier system at their disposal as their East German counterparts, it was considered difficult to cross the Czechoslovak border undetected. Primarily, they depended upon border patrols and signal fences to halt would-be escapees.

The PS used six types of border patrols:

- Control patrols checked the barrier system and inspected the credentials and permits of personnel found in the restricted zone.

- Observation patrols conducted intelligence reconnaissance of sections of the border from camouflaged positions, reporting on the movements and activities of Western border agencies.

- Alert patrols checked the signal fence for possible short circuits and responded to possible escape attempts.

- Performance patrols checked on the alert patrols and the general efficiency of the border guards by short circuiting the signal fences and then concealing themselves in order to observe the efficiency of the alert patrols when they responded to the alarms.

GSM 5-1-84

[195]

(U) Czechoslovak border markers

[196]

(U) A Czechoslovak steel 3-legged watchtower.

[197]

- Technical patrols performed general maintenance along the border area.

- Aerial patrols were conducted by the Czechoslovak and Soviet air forces. Normally, they were looking for large groups of unauthorized personnel in the border areas.

As a rule, the PS used vehicle and foot patrols as well as guard or observation towers to secure the border. Observation towers were not normally occupied at night or during periods of limited visibility. At these times, the guards remained at the foot of the towers, and foot patrols accompanied by dogs secured the border. Czechoslovak guard towers in the early 1970s were made of wood and stood approximately 10 meters high. They were similar to the East German watch-towers except that they had an exterior catwalk around the edge. By the end of the decade, they had begun building 3-legged steel towers.

Up until the first part of the 1970s, they normally used a single strand barbed wire fence along the border, but at that point they increasingly began to rely on the U-60 Signal Fence, which consisted of a 2-meter high strand barbed wire fence strung on "T" shaped concrete fence posts and employing an electrical signal device. A person attempting to get through the fence, over it, or to cut it would activate an alarm at the nearest PS command post, which would dispatch an alert patrol to the alarm area. It was easily identifiable because when the alarm was set off, a light on the fence would illuminate and stay on until reset by the alert patrol personnel. It was and is difficult to determine how extensively they used the U-60 Signal Fences in that they often built them out of sight behind the tree lines, anywhere from 100 meters to 4 kilometers from the border. They began building an improved model in 1977 that was approximately 20 centimeters higher, used a rust-free barbed wire, and mounted the signal devices on wooden brackets which allowed them to keep the fence turned on during thunderstorms.

The patrols were supplemented by well-trained attack dogs, which allegedly were cross-breeds of female wolves and male German shepards. In areas the PS considered high risk routes of escape, it often constructed cable runs and attached guard dogs, who could run the entire length of the cable. The Czechoslovak border guards relied heavily on their attack and guard dogs to secure the border. The attack dogs, used on patrol, would attack only on voice command and would give silent warnings of the presence of a border crosser. The

GSM 5-1-84

[198]

guard dogs were less intelligent and usually more excitable, not necessarily a handicap for a dog whose main function was to detect intruders and give warnings.

The border area was marked off by a series of zones that controlled access to it by the normal citizen. There was a variable 6- to 12-kilometer restricted zone in which only those who had been cleared for political reliability and possessed a special pass could reside. Next to the border were forbidden or "dead zones of from 2 kilometers in wooded or rough areas or 10 to 12 meters in heavily populated areas. And immediately on the border was an approximately 80-meter border zone that was posted with a sign stating: "Border Zone. Admission Only By Special Written Authorization."

In areas that were considered likely routes of escape, the barrier system was elaborated with three fences -- two outside barbed wire fences with a taller signal fence in the middle. The space between them contained more barbed wire and signal flares. In. areas they considered potential major routes of attack, they often built steel hexagons and concrete tetrahedrons. In earlier years, they had plowed and raked a 3- to 5-foot wide clear zone between the border and the main barrier, which permitted the guards to check for footprints. In recent years it was extended to approximately 24 feet in front and behind the signal fences.

Other improvements in the system during this period were the installation of searchlights and floodlights, paved access roads in some areas to facilitate the movements of the motorized patrols, and the use of East German-style metal grid fences in some sectors. There were indications they considered using SM-70 mines during the mid1970s, but as of the end of this report, the Czechoslovak border contained no known mine fields or firing devices. There had been reports that they employed a pseudo-mine that exploded with a loud bang when activated and, of course, they used trip-wire flares both on the barrier and close by. One interesting experiment they were trying was a device that connected a loudspeaker and tape recorder to the signal fence. When the fence's alarm system was activated, a tape was played of barking dogs, rifle shots, and the command to stand still.

(U) The Czechoslovak border barrier system, even with these improvements, remained less formidable than the East German system. (See FIGURE 13 for a pictorial description of the modern Czechoslovak border barrier system.) However, it was this low visibility of their system that constituted the greatest danger for US border operations.

GSM 5-1-84

[199]

FIGURE 13

[200]

It was extremely easy to unintentionally pass over the border and create a messy international incident. Traditionally, the Czechs reacted less violently than the East Germans, but as an American observation helicopter that strayed over the border in the spring of 1984 discovered, they would react and in that instance they reacted with bullets and possibly a rocket.18

(U) In May 1972 V Corps implemented a border tour program designed to familiarize all V Corps soldiers with the inner German border. This was particularly appropriate at this point as the modernization program had begun in earnest during this period. Mandated by V Corps Regulation 381-3 (28 April 1972) during the first year, the tour was made voluntary during the second year, with no appreciable difference in participation: 6,977 soldiers and 1,073 other personnel in 1972 versus 7,087 soldiers and 976 other personnel in 1973. The key to this extensive participation was that V Corps commanders viewed the border tour program as an important method of showing their soldiers why their units were stationed in Europe. The tours were conducted from March through November, Tuesday through Thursday each week, by V Corps' two 11th ACR squadrons. VII Corps began its border tour program on 1 April 1974 and, between then and 22 November, conducted 273 tours for 10,488 soldiers and family members. V Corps took 7,514 soldiers and family members to the border in 1974, a drop in corps participation due to suspension of funds for the border tour program. (Presumably, they were referring to corps funding, with the bill being picked up by the individual units from this point on).19

(U) The V Corps commander directed in August 1972 that a training film be prepared that would depict representative portions of the inner German border and outline the evolution of the barrier system from 1952 to the construction of the modern barrier system up through 1972. Entitled "The Evolution of Shame" and released in March 1973, copies were distributed to V Corps units along with a background briefing which gave the historical and political significance of the inner German border and the barrier system. The film was given wide exposure in the units and shown to new arrivals as well as other audiences.20

(U) In December 1973 V Corps presented an orientation on border operations to the Frankfurt chapter of the Association of the US Army (AUSA). The presentation included items of East German uniforms and weapons, as well as samples of the materials being used in the modern-

GSM 5-1-84

[201]

(U) V Corps soldiers visit the "Freedom Tower" located on a hill overlooking the inner-German boundary. The "Freedom Tower" was used during the first year of the Border Tour Program in 1972.

[202]

ized barrier system. The highlight of the presentation was a showing of "The Evolution of Shame." With the border tour program, the film, and public affairs programs such as the AUSA presentation, V Corps was trying to make its "constituency" aware of the importance of border operations and, indirectly, why the US Army was in Europe.21

(U) Current Stationing and Force Structure

(U) When the 1970s began, USAREUR was still conducting its border operations with the 14th Armored Cavalry Regiment in the north (V Corps area of responsibility) and the 2d Armored Cavalry Regiment and the 2d Squadron of the 14th Armored Cavalry Regiment in the south (VII Corps area of responsibility). (For a complete breakdown of stationing during this period, see Chapter 5, Force Structure and Stationing at the End of the 1960s.) As the Vietnam conflict began to wind down the Army initiate a program to retain in the active Army those units with the longest and most distinguished traditions. This program affected two of the border units, the 14th Armored Cavalry Regiment and the 122d Aviation Company. The 14th Armored Cavalry Regiment was inactivated on 17 May 1972 and reorganized as the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment on the same day. The 2d Squadron of the 14th ACR, which was under the operational control of the 2d ACR at this point, became the 2d Squadron of the 11th ACR. The rationale for the redesignation was that the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment was returning from service in Vietnam and, supposedly, had a more distinguished history and traditions. However, in 1983 there were still former 14th ACR soldiers serving in the 11th ACR who would argue that this was not necessarily so, and that the Army had overlooked the 14th ACR's long and continuous service on the Federal Republic's eastern border. The 122d Aviation Company, which was located at Hanau and operated the SLAR program (see below, Aerial Surveillance Along the Border), was inactivated on 11 September 1972, wit the Aviation Company being activated from its resources.22

As a result of the 1967 REFORGER action and the withdrawal of the 3d Armored Cavalry Regiment to the United States in 1968 (see Chapter 4, Force Structure and Stationing at the End of the 1960s), USAREUR had been using only two armored cavalry regiments to perform the border screening and surveillance mission in the Central Army Group (CENTAG) area of responsibility. Wartime responsibilities in CENTAG were divided among the US V Corps, from the CENTAG boundary with the Northern Army Group (NORTHAG) on a line north of Kassel to a point east of Fulda; the US VII Corps, from the V Corps southern boundary to a point on the Czechoslovak border east of Bamberg; and the

GSM 5-1-84

[203]

(U) On their way to patrol the border soldiers from the 2d Armored Cavalry Regiment enter a forest near Brand. August 1974.

[204]

German II Corps, from the VII Corps southern boundary to the Austrian border.

Based on a 1964 bilateral US-FRG agreement, however; the peacetime border surveillance mission in the German II Corps sector was performed by the US VII Corps, so that the VII Corps peacetime sector extended all the way from the V Corps southern boundary near Fulda to the German-Austrian border near Passau. To facilitate coverage of this long stretch of border, in February 1967 USAREUR had attached the 2d Squadron of V Corps' 14th Armored Cavalry Regiment to VII Corps' 2d ACR. When the 14th ACR was inactivated and reorganized as the 11th ACR in 1972 (see above), this arrangement was continued in force.

The attachment of a V Corps' armored cavalry squadron to VII Corps led to a number of problems: It reduced tactical flexibility and increased command and control problems; it led to inefficiency because one ACR headquarters controlled only two squadrons, while the other controlled four; and it caused numerous administrative, logistic, and morale problems in the attached squadron. In 1971 the VII Corps commander had recommended ending the border surveillance mission in the German II Corps sector so as to shorten the sector for which he was responsible, and in early 1972 the 2d ACR commander proposed redesignating the attached squadron as a squadron of his regiment so as to eliminate the administrative, logistic, and morale complications of the existing situation.

To resolve these questions, the USAREUR Chief of Staff directed in May 1972 that a study of border surveillance operations be made to determine whether the mission in the German II Corps area should be transferred to the Federal Republic, whether peacetime border responsibilities in the US sector should parallel wartime areas of responsibility, and whether divisional armored cavalry squadrons should be assigned peacetime border surveillance responsibilities.

The Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff, Intelligence (ODCSI), was strongly opposed to a transfer of responsibility for the German II Corps sector. While such a transfer would have been sound in terms of doctrine and would have given the Federal Republic responsibility for peacetime surveillance in its own wartime sector, it would have weakened seriously USAREUR's overt intelligence collection effort along the Czechoslovak border. The Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff, Operations (ODCSOPS), shared that view and also argued that such a transfer would restrict USAREUR's flexibility in reacting to

GSM 5-1-84

[205]

contingencies and eliminate part of the deterrent arising from a US presence on the border.

Accordingly, USAREUR headquarters considered it desirable to retain the border surveillance mission in the German II Corps sector and continue the existing peacetime areas of responsibility within the US sector because these paralleled the wartime areas of tactical responsibility assigned to the two US corps. The obvious disadvantages of the existing organizational concept could be corrected by returning operational control of the 2d Squadron of the 11th ACR to its parent regiment, shifting elements of the 2d ACR laterally so as to place them all within-the VII Corps sector, and performing the out-of-sector German II Corps surveillance mission with VII Corps assets not belonging to the 2d ACR.

Four options were considered for accomplishing the latter course of action: attaching a divisional cavalry squadron to the 2d ACR, attaching on a rotating basis a troop of a divisional cavalry squadron to the 2d ACR, deploying a squadron of the 3d ACR (a USAREUR assigned unit stationed in the United States under the REFORM concept to VII Corps, or combining the first option on an interim basis with the third option as an ultimate solution.

The first option had several advantages: It would place the squadrons of the 2d ACR near their emergency defense plan (EDP) positions in peacetime, would afford each corps commander control over the peacetime border operations in the corps' wartime sector, would give the corps commanders control over the training and readiness of their screening cavalry units, and would facilitate the reporting of intelligence gleaned from border surveillance operations to the responsible commanders. The only significant disadvantages would be to deprive one of VII Corps' divisions of its initial cavalry capability and to reduce EDP cavalry strength in the VII Corps sector.

The second option would provide an increase in border surveillance capabilities with accompanying training advantages for the divisional cavalry units performing the border mission. Like the first option, it would also return the 2d ACR squadrons to the vicinity of their EDP positions. The major disadvantages of this option were that the attached cavalry troop might well be out of sector when hostilities commenced; each of the rotating troops would require border orientation before assuming the mission, thereby reducing the time available for normal unit training; and a special contingency plan would be needed to provide for the reinforcement of the attached troop when increased surveillance was called for.

GSM 5-1-84

[206]

The third option was particularly attractive in that it would provide a highly visible increase in VII Corps' cavalry assets, permitting the return of the 2d Squadron to its parent unit without reducing VII Corps' capability and without requiring the diversion of a divisional unit from its primary task. The major drawbacks were the expense of deploying a unit from the United States and the concomitant increase in total manpower strength in Europe (or the need to accept a trade-off to avoid such an increase). Stationing of the unit would also have presented certain problems because of the limited facilities available in USAREUR. The advantages and disadvantages of the fourth option were the same as those of options one and three.

V Corps concurred in the proposal to return the 2d Squadron of the 11th ACR to its control, while VII Corps objected. Citing the disadvantages listed above for the various options of the USAREUR proposal, VII Corps insisted that any reduction in its cavalry screening capability would degrade seriously the corps' defense concept. Only the deployment of a squadron of the 3d ACR from the United States would provide a satisfactory alternative to the existing arrangement.

Because of the disadvantages of any change that did not include the deployment of a cavalry squadron from the United States, and in light of the fact that political and economic considerations made such a deployment impractical, the issue remained unresolved at the end of 1972. Late in the year, however, another option was considered. The 2d Squadron would be returned to the command and control of the 11th ACR and, to overcome the objections of VII Corps, the peacetime responsibility for border operations in the sector currently assigned to the squadron under VII Corps could also be assigned to V Corps. Such a course of action would have preserved unity of command and peacetime border responsibilities, and the only significant problem would be to establish adequate arrangements that would assure the provision of timely intelligence and operational reports from the 2d Squadron to VII Corps in peacetime and that would facilitate the efficient transfer of control over the squadron to VII Corps upon declaration of a state of military vigilance.

In January 1973 USAREUR headquarters announced it would make these changes in command and border responsibilities. On 1 March 1973 command of the 2d Squadron of the 11th ACR reverted back to the 11th ACR and V Corps. Concurrently with the change of command, responsibility for peacetime border operations in the VII Corps sector covered by the squadron also passed to V Corps (grid coordinates NA 740970 to PA 145665), which increased the total area under V Corps control from

GSM 5-1-84

[207]

(U) Soldiers being inserted along the border as a test of unit readiness. Aircraft is an OH-58 Kiowa.

[208]

269 kilometers to 385 kilometers. There were no changes in stationing of the unit elements; the existing tactical alert net procedures remained in effect, providing direct communications between the squadron and VII Corps; and existing community support and corps logistic support arrangements continued in effect, with V Corps reimbursing VII, Corps for logistic support after 31 March.

Operational control of the 2d Squadron would pass to VII Corps on declaration of military vigilance or a higher state of alert. Accordingly, copies of logistic and operational readiness reports were provided to VII Corps, as were copies of all border intelligence and border incident reports. In addition, in order to permit VII Corps to practice wartime procedures in peacetime, operational control of the 2d Squadron automatically passed to VII Corps during readiness tests initiated by higher headquarters and would revert to V Corps automatically upon termination of the exercise. When USAREUR subsequently adopted a 2-step exercise implementing procedure, involving the use of a notification to prepare and a notification to execute, the time of assumption of operational control by VII Corps was defined as being upon receipt of the "execute" message.23

(U) In 1974 a USAREUR headquarters study group began an in-depth 2-year study of USAREUR's aviation resources, its overall goal being to strengthen Army aviation's combat posture in Europe by integrating its tactical, logistic, and administrative support functions. With the projected large-scale expansion of USAREUR's Cobra/TOW* attack helicopter inventory, it evolved into a study for developing the optimum organization for integrating the AH-1Qs into the combined arms team in the central European region. Among the various proposals tested during this period was that of a TOE calling for an anti-armor troop (AAT), composed of 21 AH-1Qs, and a combat support troop (CST), which would provide logistic support and command and control. The 2d Armored Cavalry Regiment tested a combination of these two elements in an air cavalry troop (provisional) during the first half of 1975, which evolved into an interim organization called an air cavalry troop (heavy) on 1 September 1975.** Recommendations of this portion of the

* (U) TOW: A tube-launched, optically-tracked, wire-guided, antitank missile.

** (U) The regimental aviation companies, which had been organized to centralize the aviation assets of the regiments in May 1960, had been reorganized and redesignated in subsequent years, first as air cavalry troops on 1 September 1967 and then as air troops on 15 March 1968. For several years during the mid-1970s, the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment referred to its unit as the Anti Armor Helicopter Troop (AAHT). (USAREUR GOs 142, 10 May 1968; and 378, 26 Aug 68. UNCLAS.)

GSM 5-1-84

[209]

USAREUR study stated that although there were advantages to having just one basic TOE for these two functions, the new unit would need a 'support cell" added on to provide the logistic functions.

(U) The final study report, forwarded to Department of the Army in April 1976, split the two basic functions up again and recommended that an attack helicopter troop and a support troop be assigned to each armored cavalry regiment. Department of the Army approved-the proposed reorganization, and, throughout the rest of the year USAREUR began concentrating its limited number of attack helicopters in the two armored cavalry regiments. The air elements in the 2d ACR and 11th ACR were reorganized on 21 January 1977 as air troops, each of which contained 21 Cobra/TOW attack helicopters, and support troops (air), which incorporated the regimental support aircraft (mostly UH-is and OH-58s). The 11th ACR, however, referred to its support troop (air) as a combat aviation troop.24

In 1983 USAREUR conducted border operations between map grid coordinates NB 6492 (in the vicinity of Hebenshausen) and VQ 1503 (at the intersection of the Federal Republic, Austrian, and Czechoslovak borders), a distance of approximately 1,036 kilometers or just over 642 miles. The V Corps' area of responsibility, covered by the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment, included 385 kilometers of the inner German border (NB 6492 to PA 1467). The VII Corps' area of responsibility, monitored by the 2d Armored Cavalry Regiment and two divisional cavalry elements, encompassed a distance of 651 kilometers, which included portions of the inner German border and all of the Czechoslovak border adjacent to the Federal Republic (PA 1467 to VQ 1503). The southern .VII Corps boundary was moved from VQ 1403 to VQ 1503 sometime between late 1972 and early 1974. It should be noted that the actual map grid coordinates have changed over the years as coverage of the border was increased or decreased (most of the major changes were outlined in this study) and that the measurements given between the map coordinates varied, apparently depending upon the method used to measure the border trace. The figures used here seem to have a "consensus" accuracy, but may not please all of the readers of this study.25

In 1983 the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment, with headquarters in Fulda (Downs Barracks), divided up the V Corps' border sector as follows, from north to south (see MAP 11):

- The 3d Squadron headquarters was located at Bad Hersfeld (McPheeters Barracks) and operated Observation Posts India (NB 802581)

GSM 5-1-84

[210]

MAP 11

[211]

and Romeo (NB 694457) for the border sector between NB 647922 and NB 713416. Observation Post Oscar, mentioned in earlier lists of 11th ACR active observation posts, was phased out on 1 December 1976, but in 1983 the 11th ACR was considering opening another observation post in order to have better coverage of the squadron sector. This plan was subsequently shelved.

- The 1st Squadron headquarters, collocated with the regimental headquarters at Fulda (Downs Barracks), operated Observation Post Alpha (NB 658198) for the sector from NB 713416 to NA 739967.

- The 2d Squadron headquarters, located at Bad Kissingen (Daley Barracks) and in Camp Lee, operated Observation Post-Tennessee (NA 946939), which had formerly been named Sierra, for the sector between NA 739967 and PA 144671.

- The regiment also had a Combat Aviation Squadron (formerly called the Command and Control Squadron), which among other things included the air troop and support troop (air) elements mentioned above and was located,at Fulda. It had the task of providing regimental aerial surveillance along the entire V Corps' sector.

- In addition, the 3d Squadron of the 12th Cavalry, which belonged to the 3d Armored Division, and the 3d Squadron of the 8th Cavalry, which belonged to the 8th Infantry Division, conducted border operations when 11th ACR units were training or needed augmentation.26

The 2d Armored Cavalry Regiment, with headquarters at Nuernberg (Merrell Barracks), conducted border operations in the VII Corps' sector as follows, from north to south (see MAP 12):

- The 3d Squadron of the 7th Cavalry (3d Infantry Division) had been placed under the operational control of the 2d ACR for border operations only in September 1977 and was responsible for the border sector from PA 136760 to PA 607713. It operated out of Camp Coburg (PA 409708).

- The 2d Squadron of the 2d ACR was head quartered at Bamberg (Warner Barracks) and operated out of Camp Hof headquartered 056780). It was responsible for the border sector between PA 607713 and QA 119854.

- The 1st Squadron of the 2d ACR was headquartered at Bindlach (Christensen Barracks) and operated out of Camp Gates (TR 962430). It was responsible for the border sector between QA 119854 and UR 140426.

GSM 5-1-84

[212]

MAP 12

[213]

- The 1st Squadron of the 1st Cavalry (1st Armored Division) had been placed under the operational control of the 2d ACR for border operations only in November 1978 and was responsible for the border sector from UR 140426 to UQ 293890. It operated out of Camp Pitman (TR 937064). (Camp Weiden was renamed Camp Pitman.)

- The 3d Squadron of the 2d ACR was headquartered at Amberg (Pond Barracks) and operated out of Camp Reed (UQ 183658) (Camp Rotz was renamed Camp Reed) and Camp May (UQ 584281). It was responsible for the border sector from UQ 293890 to VQ 148029.

- Early in the 1970s, Camp Wollbach and Camp Phillipsreut had been used in the VII Corps sector, but by 1974 they were no longer listed as active border camps.

- The 2d ACR also had a Command and Control Squadron (Provisional), which included the air troop and support troop (air) that accomplished the regimental serial surveillance mission as well as other regimental elements and was stationed at Merrell Barracks and Feucht Army Airfield in Nuernberg. The air troop, designated Attack Helicopter Troop, conducted surveillance in the Weiden and Regen sectors, while the support troop (air), designated Support Helicopter Troop, had responsibility for the Hof and Coburg sectors.27

(U) Organizationally, the two armored cavalry regiments were similar in most respects. In addition to regimental headquarters elements, each regiment-was composed of three line squadrons and a provisional command and control squadron. Each line squadron consisted of a headquarters and headquarters troop and three cavalry troops as well as a tank company and a howitzer battery or troop. The line-up was as follows: 1st Squadron - A, B, and C Troops, and D Company (tank); 2d Squadron - E, F, and G Troops, and H Company (tank); and 3d Squadron -I, K, and L Troops, and M Company tank) -- plus an unlettered howitzer battery or troop for each squadron. The command and control element -- Command and Control Squadron (Provisional) in the 2d ACR, or the Combat Aviation Squadron, as it was named in the 11th ACR -- was composed of an air troop and a support troop (air), under various names in each unit, as well as a headquarters and headquarters troop, an engineer company and, in the 2d ACR, an Army Security Agency (ASA) company. The divisional cavalry squadrons that augmented the two regiments, either full- or part-time, were organized much as their counterparts except that they were usually short howitzer batteries and tank companies, but sometimes had air troops.

GSM 5-1-84

[214]

(U) Equipment Modernization in the Border Force

(U) There were major changes in the equipment and vehicles being utilized by the border units in the 1970s and forward. In many respects, the units had not significantly changed the equipment they had been using for the border surveillance mission since the end of World War II through the late 1960s period. The ACR vehicle patrols still used the old workhorse, the M151 jeep, and visual aerial surveillance had been accomplished from light fixed-wing aircraft and, subsequently, a limited number of helicopters. Things began changing in the late 1960s and really picked up speed in the 1970s, when the border units began deploying a wide range of new equipment and vehicles. In addition to receiving more and newer tanks and armored personnel carriers (APC), which were not all that important to the surveillance mission, perhaps the most significant change was the large-scale introduction of attack helicopters into the units, which had border surveillance as a secondary mission. This greatly increased the ACRs' capability of accomplishing their traditional missions of conducting surveillance and providing a light screening and covering force. The more exotic aerial surveillance equipment mounted on fixed-wing aircraft introduced during this period will be covered below in the section on Aerial Surveillance Along the Border.

(U) An important upgrade in the armored cavalry regiments' aircraft fleet occurred in November 1969 when the 2d ACR began accepting OH-58 Kiowa observation helicopters. The OH-58s were to replace the regiments' OH-13 Sioux helicopters and 0-1 Bird Dog fixed-wing aircraft. Of greater importance was the introduction of 12 AH-1G Cobra attack helicopters in 1970, with 6 being given to the 2d ACR for use along the border. They were scheduled to replace the UH-1B Iroquois helicopters, but, because of the ongoing Vietnam conflict, the units received a very small number of the Cobras until the mid-1970s, when larger numbers became available for deployment in Europe (see above, Current Stationing and Force Structure). The UH-1Bs that were capable accepting armament were transferred to the air cavalry troops for use as gunships, with the remaining helicopters being programed to be sent back to the United States during 1970-71. After the mid-1970s, when the aviation assets of the armored cavalry regiments were reorganized into air troops and support troops (air), the units utilized OH-58s, UH-1s, and AH-1s on the border.28

(U) Upgrades of the armored cavalry units' tank and APC inventories were ongoing initiatives throughout this period. The workhorse of the tank fleet was the M60 main battle tank, with M113 APCs serving

GSM 5-1-84

[215]

(U) OH-58A Kiowa

[216]

(U) AH-1G Huey Cobra

[217]

as the mainstay of the armored personnel carrier fleet once the upgraded version (M113A1) was completely deployed in 1971. The M114 APC was also utilized, but it had a history of mechanical unreliability and was considered underpowered for its mission. And, by March 1971, the armored cavalry units had been equipped with their initial quota of the new M551 Sheridan light tanks, which consisted of 27 vehicles for each squadron for a total of 279 in armored cavalry units (4 divisional squadrons, 3 squadrons each in the 2 armored cavalry regiments, and 1 troop in the 1st Infantry Division (Forward)). (See Chapter 5, Equipment Changes in the Border Units, for information on the deployments of most o these vehicles in the 1960s.)

(U) In September 1970 the Department of the Army had proposed a "one for one" exchange of M551 Sheridans for the M114 scout vehicles in the divisional cavalry platoons and three of the six regimental squadrons. USAREUR initially opposed the proposal because it thought it would cause an additional maintenance burden, increase the need for personnel, and degrade the cavalry platoons' reconnaissance capability. However, in early 1971 a compelling argument was made that the additional M551s were needed because of their antitank capability and the above mentioned problems with the M114s. Equipped with a dual-purpose 152mm tube weapon that fired conventional rounds and served as a launcher for the Shillelagh guided missile, the Sheridan was capable of destroying armor at ranges up to 3,000 meters. In April 1971 USAREUR informed Department of the Army that it was willing to deploy three additional M551s in each armored cavalry platoon, for a total of six. The three M551s would replace the scout section's five M114 APCs and double the cavalry squadron's antitank capability. USAREUR emphasized that its acceptance of this interim solution should not be construed as agreement that the long-awaited armored reconnaissance scout vehicle ARSV) be deferred indefinitely, which seemed to be the prospect in 1971-72. Throughout 1972 the promised M551s were diverted to the 3d Armored Cavalry Regiment in the United States, but in January 1973 they began to arrive in-theater and the swap-out was completed by the end of April 1974, bringing the armored cavalry units' inventory of M551s up to 558. The latter group of M551s (involved in the M114 trade) had the new laser range finders. The older M551s were modified by 1976. The remainder of the ACRs' M114s, used as command and control vehicles, had been replaced by M113Als in 1973.29

Unfortunately, the M551 Sheridan also developed a history of unacceptable performance, this time due to low weapon system reliability. General Motors had experienced extensive development problems

GSM 5-1-84

[218]

(U) M551 Light Tank (Sheridan)

[219]

with the vehicle, but it had finally been declared ready for fielding on 29 March 1966. Production of the M551 had been marred by an excessive number of retrofits and modifications, many of which were on the gun/launcher subsystems. After being fielded in USAREUR in 1969, the M551 continued to have reliability problems; however, the extent of the problems had not been identified in the normal readiness reporting systems because of the systems' scoring rules, and thus led to inflated operational readiness rates. The 2d Armored Cavalry Regiment carried out a test under quasi-combat conditions, which gave a more valid picture of the M551's reliability. Its data showed that of a possible 322 missile shots, 113 (or 35 percent) would not have launched dub to some kind of malfunction. Only about 50 percent of the vehicle systems were actually capable of firing a missile at the appropriate moment, a sad situation for units placed on the border who would be the first to encounter an enemy in the event of an attack. The 11th ACR subsequently experienced much the same failure rate for missile shots (33 percent). In addition, these tests revealed that the shock of firing conventional rounds prior to a missile often caused Shillelagh system failure. After an extensive Product Improvement Program (PIP) could not elevate the system's reliability, it was determined the M551 was unacceptable and could not accomplish its combat mission.

Concurrently -- since it was already obvious that something was seriously wrong with the M551s -- studies were conducted to determine a replacement system, to formulate a phase-out plan, and to examine future uses for the vehicle. In addition, an extensive 2-year assessment by the Armor Center at Fort Knox of cavalry requirements for modern armor battle had culminated in November 1976 with a new TOE for armored cavalry units, the main feature of which would be the replacement of the M551 with main battle tanks from the M60A1 series. The M551's unreliability and the Armor Center's call for heavier armor for cavalry units culminated in the Department of the Army announcement on 6 February 1978 that the six M551s in each cavalry platoon would be replaced with four M60A1 (RISE-Passive)* tanks. Each cavalry squadron would replace a total of 54 M551s with 36 tanks, and 2 separate cavalry troops would receive 12 tanks each. Under the reorganization, the cavalry platoons would be universally the same: five M113

* (U) The RISE-Passive modification packs. a for the M60A1 consisted of reliability improved selected equipment RISE), which included the AVDS-1790 RISE engine with 19 automotive improvements, and "passive" night sights which utilized image intensifying technology.

GSM 5-1-84

[220]

APCs (two of which would be equipped with TOW) and four M60A1 main battle tanks. Improved TOW Vehicles (ITVs) (see below), were to be issued in FYs 1979-80 on the basis of 18 to each cavalry Squadron and 6 to each separate troop.

Department of the Army developed a four-phased approach for withdrawing the M551s from the inventory, with Phase I being their removal from all USAREUR units. In June 1978 the 1st Squadron of the 11th ACR began the swap-out and, by 1 April 1979, the last USAREUR unit -- the 1st Squadron of the 4th Cavalry -- ad completed the conversion. Basically, the replacement went smoothly, with reactions of unit personnel varying from a sigh of relief to a certain nostalgic sense of loss. Several crew members felt the M551's problems had finally been worked out and that it was more than adequate for the cavalry mission. They particularly liked the Sheridan's superior maneuverability and light weight, but these factors were not considered as important as the continued unreliability of the firing system or its lack of heavy armor on the modern battlefield. One cavalryman summed it up as follows: "We can get the job done with the Sheridan, but most cavalrymen would rather have the tank."30

Almost as soon as the regiments completed their conversions to M60A1s, the decision was made to replace them with the M60A3, an upgraded version of the M60A1 (RISE-Passive) that incorporated much of the improved fire control system of the developmental M1 tank. The 1st Squadron of the 10th Cavalry became the first USAREUR cavalry unit to receive the M60A3 in 1979, and was followed by all three squadrons of the 11th ACR and the 3d Squadron of the 8th Cavalry in 1980. Because of delays in delivery of fire-control components, the three squadrons in the 2d ACR and other divisional cavalry units were not finished converting to the upgraded tank until the first part of 1982. On 10 August 1983 Troop A of the 1st Squadron of the 11th ACR unloaded 12 of the new Abrams M1 tanks and became the first USAREUR cavalry unit to receive the new main battle tank. The 2d ACR was scheduled to begin receiving M1s in 1984. Planning in 1983 called for the armored cavalry regiments' squadrons to receive 17 M1s for their tank company and 36 M1s for the 3 reconnaissance troops for a total of 53 per squadron, or 159 M1s for the entire regiment. The fielding of the new Bradley Fighting Vehicle in the regiments in the FYs 1985-87 period would result in a reduction to only 129 M1s in each regiment.31

(U) In addition to the M60A3 and M1 tanks, the cavalry units received another vehicle that increased their tank killing capability. The M901 Improved TOW Vehicle (ITV) was intended to be an interim

GSM 5-1-84

[221]

(U) M1 Main Battle Tank (Abrams)

[222]

substitution for the M3 cavalry fighting vehicle and consisted of a 2-launcher TOW elevating turret mounted on an M113 APC chassis. Although tests in the United States in 1979 had demonstrated that the M901 had only a limited capability as a scout vehicle, CINCUSAREUR thought its tank killing ability warranted it being issued to all of the cavalry units in USAREUR. V Corps concurred in this plan, but VII Corps wanted to limit distribution to only the divisional and brigade cavalry units, but not to the 2d ACR. As a consequence, the 2d ACR was scheduled to be the last unit to receive the new vehicles. Deployment of the M901 in USAREUR began in January 1980, with. 18 vehicles being issued to the 1st Squadron of the 11th ACR. The basis of issue was to be 18 vehicles per cavalry squadron, both divisional and regimental, and 6 for the cavalry troop of the separate brigades. The 11th ACR had received its full quota by the end of 1980 and the 2d ACR had accepted its M901s by the end of the first quarter of 1982, for a total of 54 M901s in each regiment.32

A major improvement in the surveillance capability of the border units had occurred in 1961 with the introduction of the AN/PPS-4 ground surveillance radar (GSR). (See Chapter 5, Equipment, Changes in Border Units.) Generally, they were used on the border during periods of reduced visibility and the hours of darkness. An improved GSR -- the AN/PPS-5 -- was tested by V Corps units in 1971, and found to be more effective than either the AN/PPS-4 or the subsequently introduced AN/TPS-33 GSRs. The AN/PPS-5 was a portable, battery-powered ground surveillance radar designed for battlefield use in locating and identifying moving ground targets. It was based on the Doppler principle and registered targets as wave forms on two scopes and as electrical signals through headphones. The AN/PPS-5 increased the line-of-sight range of ground surveillance radar from 6,000 meters to 10,000 meters for vehicles and from 1,500 meters to 6,000 meters for personnel. In 1971 the armored cavalry units were scheduled to receive 2 AN/PPS-5s for each troop, for a total of 6 per squadron or 18 per ACR. Although the two border regiments received priority when field issue of the new GSRs began in the latter part of 1971, they were still short their full quota as late as 1973. However, by 1976 some of the divisional GSR sections or teams had received their new sets and they began augmenting the ACRs' GSR coverage on the border. The divisional GSR sections' augmentation was rated a success, and in 1977 they began regular 14-day operations periods- at field vantage points where significant border activity had been identified. (Prior to this, they had operated at the observation posts.) Starting with their introduction in 1961, the GSRs had a history of maintenance problems and had been difficult to man with fully trained

GSM 5-1-84

[223]

(U) AN/PPS-5 Ground Surveillance Radar

[224]

personnel. In spite of these ongoing problems, they were still an important means for conducting routine border surveillance. And, their assignment to the border mission provided their crews with invaluable, real-mission experience they could never obtain during exercises or at training areas.33