Army Art Posters and Prints

SOLDIERS OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION - by H. Charles McBarron

CMH Pub 70-5;

Not Available through GPO sales.

10 full-color 22 1/4" X 17 1/4" color reproductions of paintings depicting the American soldier in important episodes in the nation's fight for independence. This set includes a booklet describing each print in detail. The following 10 prints are available in this print set. Individual prints may not be requested.

* View this publication online.

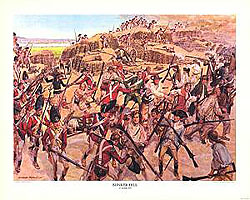

Bunker Hill, 17 June 1775

After the British rout from Lexington, a loosely organized New England army of volunteers and militia laid siege to Boston. The British commander, Sir Thomas Gage, determined to gain more elbowroom by seizing the Charlestown peninsula. Learning of Gage's plans, the Massachusetts Committee of Safety recommended the occupation of Bunker Hill, a commanding height near the neck of the Charlestown peninsula. But a working party of 1,200 Americans, sent out on the night of 16-17 June 1775, instead fortified Breed's Hill, a lower height nearer Boston.

When the British awoke next morning, they saw a fortification with walls six feet high astride Breed's Hill. Determined to take the barrier by assault, a force of 2,200 Redcoats under Sir William Howe landed on the Charlestown shore in early afternoon 17 June, and launched a well-planned three-pronged attack. The Americans, who had been reinforced during the morning, repulsed the British assault with devastating musket fire. Howe had to resort to frontal attacks on the American redoubt to avoid a costly defeat of British arms. After enduring two volleys that tore huge gaps in their lines, the Redcoats converged on the American forces in a final three-column attack. The Patriots, running out of ammunition, used their muskets as clubs against the British bayonets. Colonel William Prescott, seeing the damage wrought by the Regulars, ordered his men to "twitch their guns away." The homespun-clad Americans contested every inch of ground, but finally were forced to retreat from t he peninsula.

Bunker Hill gave its name to the battle fought on Breed's Hill. For the British it was a Pyrrhic victory, their losses amounting to over 40 percent of the forces engaged. A force of New England townsmen and farmers had proven its ability to fight on equal terms with British Regulars when entrenched in a fortified position.

Montreal, 25 September 1775

In late June 1775 the Continental Congress, in hopes of adding a fourteenth colony and eliminating a British base for invasion, instructed General Philip Schuyler to take possession of Canada if "practicable" and "not disagreeable to the Canadians." Command of the main wing of the expedition, to march via Ticonderoga to Montreal and down the St. Lawrence, passed to General Richard Montgomery when Schuyler became ill. A second wing led by Colonel Benedict Arnold was to move on Quebec through the wilds of Maine.

Montgomery encountered strong resistance from the British at St. Johns, delaying his assault on Montreal. While undertaking a siege of St. Johns, Montgomery sent Ethan Allen and Major John Brown ahead with separate detachments to recruit Canadian volunteers. Allen and Brown did manage to recruit some Canadians and, meeting together, conceived a risky plan for a converging attack on Montreal by two forces totaling about 300 men. On the night of 24-25 September, Allen with 110 men crossed the St. Lawrence north of the town but was left to fend for himself when Brown failed to meet him. Sir Guy Carleton, British commander, sortied with a force of about 35 Redcoats, 200 volunteers, and a few Indians, and Allen, unable to recross the river, took up a defensive position a few miles from the town.

Most of the Canadian recruits fled when the first shots were fired, but Allen, constantly flanked by the Indians, led his ever-diminishing army on a fighting withdrawal for over a mile. Finally reduced to thirty-one effectives and with a British officer "boldly pressing in the rear," Allen reluctantly surrendered.

On 13 November 1775 Montgomery succeeded in capturing Montreal where Allen's premature attack had failed, but in the end the Canadian expedition was a failure. By June 1776 remnants of the American invasion force, incapable of holding their positions against a reinforced British Army, were back at Ticonderoga.

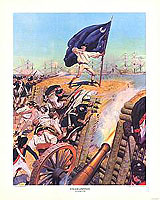

Charleston, 28 June 1776

In June 1776 British Admiral Peter Parker 'a fleet, loaded with troops commanded by General Henry Clinton, made an appearance off Charleston, South Carolina. The city, feverishly preparing for an attack, had partially completed Fort Sullivan, Charleston's key defense position. The 30-gun fort on Sullivan's Island was hastily constructed from the moat abundant materials available, palmetto logs and sand. The garrison, commanded by Colonel William Moultrie, contained over 400 men including 22 artillerists and the 2d South Carolina Provincial Regiment.

Because of a sand bar the British delayed their attack on Charleston until 28 June 1775 while they lightened ship. Clinton's 2,000 British soldiers, landing on adjacent Long Island, were unable to cross an estuary to join in the attack. The fleet began its bombardment at a range of about 400 yards. Low on powder, Moultrie directed his men to fire slowly and accurately in reply.

During the engagement a shell struck the flagpole, and the blue South Carolina banner fell outside the fort. Sergeant William Jasper retrieved it and, oblivious to British fire, secured the flag to a makeshift staff.

The falling shells, absorbed by the soft palmetto loge and sand, caused little damage to the fort and few casualties. Even shells that did enter the fort buried themselves in the swampy parade ground. The wooden frigates on the other hand were riddled with shot. One explosion blew away Sir Peter Parker's breeches.

Finally, after more than ten hours of firing, the British fleet withdrew and several weeks later sailed for New York. For three years following the defeat at Charleston the British were to leave the South unmolested and the Southern Tories, who were undoubtedly numerous, without succor.

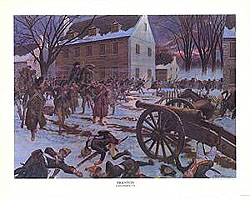

Trenton, 26 December 1776

The winter of 1776 was the bleakest of what had become a War for Independence, a time that indeed "tried men's souls." The victorious British had driven General George Washington and his army of Continentals and militia from New York. Confident that the ill-clad and ill-fed Americans would fade away when enlistments expired at the year's end, General William Howe withdrew a major portion of his force from New Jersey to the comforts of Manhattan island. Washington realized his army's only chance of survival lay in a victory over the remaining scattered garrisons of the British and their Hessian mercenaries.

On Christmas evening Washington's ragged American army left its encampment and crossed the Delaware River in a driving sleet and snow storm. At dawn, 26 December 1776, the near-frozen Continentals surged into Trenton catching the Hessians, weary from the previous night's celebration, by surprise.

Colonel Johann Rall, the garrison commander, attempted to form a line of defense on King and Queen Streets with two regiments and the Knyphausen battery. Aware of Rall's plans, the Continentals, supported by General Henry Knox's artillery and heartened by the presence of Washington, overwhelmed the guns at a dead run. The loss of the artillery position caused Rall's regiments to withdraw. Their powder damp, deprived of artillery support, their commander mortally wounded, the surviving Hessians surrendered.

Bolstered by this success Washington was able to keep his army together for several more weeks during which time he again crossed the Delaware and won a victory over the British troops at Princeton. These two engagements assured the survival of a small core of Continentals and, in turn, the survival of the American cause of Independence.

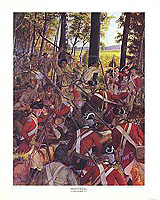

Bemis Heights (Saratoga), 7 October 1777

In June 1777 General John Burgoyne set forth on an expedition from Canada with the aim of cutting the rebellious colonies in twain by seizing the Hudson River line. With his main force he advanced toward Albany via Ticonderoga while a smaller force under Colonel Barry St. Leger moved down Lake Ontario and through the Mohawk Valley. Burgoyne's plans were not coordinated with those of Sir William Howe, the British Commander in New York, who decided to move against Philadelphia instead of attacking north along the Hudson.

Initially successful, Burgoyne suffered a crippling blow when General John Stark destroyed a detachment from his force at Bennington. Meanwhile St. Leger was forced to abandon the siege of Fort Stanwix, guarding the Mohawk Valley, and retreated to Canada. Then on 19 September Burgoyne himself suffered a repulse with heavy losses when he attempted to advance on the positions manned by the main American Army under General Horatio Gates.

Three weeks later, on 7 October 1777, Burgoyne sent out an advance force and Gates moved up Colonel Daniel Morgan's riflemen and other units to meet it. In the ensuing battle (usually known as Bemis Heights) Morgan's men, well adapted to the wooded terrain, took a fearful toll of British lives with their Kentucky rifles. One of the casualties was the fearless British General Simon Fraser. According to tradition Morgan, spotting the general, ordered one of his men, Tim Murphy, up a tree, saying that although he admired the Englishman, "it is necessary he should die, do your duty." Murphy's third shot inflicted a mortal wound.

Soon after Fraser's fall, Burgoyne withdrew and several days later, on 17 October, surrendered his army near Saratoga. The capitulation was a turning point of the war for it induced the French to sign a military alliance with the infant American Republic in February 1778.

Monmouth, 28 June 1778

On 18 June 1778, Sir Henry Clinton evacuated Philadelphia and with 10,000 men set out on a march to New York. Washington followed closely, but on 24 June a council of his officers advised him to avoid a major engagement, though a minority favored bolder action. A change in the direction of the British line of march convinced the Continental Commander he should take some kind of offensive action, and he detached a force to attack the British rear as it moved out of Monmouth Court House. General Charles Lee, who had been the most cautious in council, claimed the command from Lafayette, who had been most bold, when he learned the detachment would be composed of almost half the army.

One of the most confused actions of the Revolution ensued when, on the morning of 28 June, Lee's force advanced to attack Clinton's rear over rough ground that had not been reconnoitered. The action had hardly begun when a confused American retreat began over three ravines. Historians still differ over whether the retreat and confusion resulted from Lee's inept handling of the situation and lack of confidence in his troops, or whether the retreat was a logical response to Clinton's quick countermoves and the confusion a product of the difficulties of conducting the retreat across the three ravines.

In any case, Washington, hurrying forward with the rest of his Army to support an attack, met Lee amidst his retreating columns and irately demanded of him an explanation of the confusion. Lee, taken aback, at first only stuttered "Sir, sir." When Washington repeated his question, Lee launched into a lengthy explanation but the Commander-in-Chief was soon too busy halting the retreat to listen very long.

The retreat halted, Washington established defensive positions and the Continental Army beat off four British assaults. During the night the British slipped away. Monmouth was the last major engagement fought in the north. However inconclusive its result, it did show that the Continental line, thanks to the training of Von Steuben, could now fight on equal terms with British regulars in open field battle. It also led to the court martial of Charles Lee and his dismissal from the Continental service.

Vincennes, 24 February 1779

Warfare between frontiersman and Indian increased in intensity during the Revolution. The British from posts at Niagara and Detroit encouraged Indian attacks that harassed the westernmost settlements. In mid-1778 George Rogers Clark with about 175 to 200 men set out on an expedition sponsored by the Commonwealth of Virginia with the ostensible purpose of defending Kentucky but with secret orders to take the British posts in the Illinois country and if possible, Detroit. In July 1778 by surprise moves and by winning the sympathy of the French settlers he captured Vincennes and Kaskaskia without firing a shot.

In December 1778 Colonel Henry Hamilton, the British commander at Detroit, retaliated, recapturing Vincennes and rebuilding the dilapidated Fort Sackville there. Clark, determined not to have Vincennes remain in British hands, started out on a bold 180-mile mid-winter march from Kaskaskia to retake the fort. Fording and ferrying numerous icy streams and flooded rivers, Clark and his nearly starved men reached Vincennes on 23 February 1779. He warned the inhabitants of his approach and marched his men back and forth with many flags to create the impression of an overwhelming force. The French welcomed the Americans and the Indians fled into the woods.

After a brief fight Hamilton agreed to surrender, and on the 25th marched his garrison from the fort between two companies of frontiersmen. Looking around as he presented his sword to Clark, Hamilton is said to have exclaimed, "Colonel Clark, where is your army?" At the same moment two other American companies entered Fort Sackville and raised the American flag.

Clark was unable to achieve his goal of capturing Detroit and did not completely halt Indian attacks on Kentucky, but his amazing exploits strengthened American claims to the Northwest territory.

Guilford Courthouse, 15 March 1781

General Nathaniel Greene assumed command of the remnants of the Southern Army after Horatio Gates' disastrous defeat at Camden. In his ensuing campaign against Lord Cornwallis he sought to gain strength while harassing British forces and drawing them further from their bases on the coast. His position immensely strengthened by Daniel Morgan's victory at Cowpens (17 January 1781), Greene skillfully retreated before Cornwallis' force and finally, his ranks swollen by militia, gave battle on grounds of his own choosing at Guilford Court House, N.C.

Greene deployed his forces in three lines. The first was composed of North Carolina militia whom he asked to fire several volleys and retire; the second was made up of Virginia militia; the third, posted on a rise of ground, comprised Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware Continentals.

When Cornwallis' Regulars launched their attack, the first line of militia fired their rounds and fled the battlefield, the second line offered stiffer resistance but also withdrew. Before the second line gave way, several British units broke through and charged the last line. Greene observed as the veteran First Maryland Continentals threw back a British attack and countered with a bayonet charge. As they reformed their line, William Washington's Light Dragoons raced by to rescue raw troops of the Fifth Maryland who had buckled under a furious assault of British Grenadiers and Guards.

Finally Greene ordered a retreat, since he was determined not to risk the loss of his army. For the British it was another Pyrrhic victory. Cornwallis, his force depleted, withdrew to the coast at Wilmington and then went on to his rendezvous with destiny at Yorktown. Greene, while losing two more such battles, by October 1781 had forced the British to withdraw to their last enclaves in the South � Charleston and Savannah.

Yorktown, 14 October 1781

In the summer of 1781, ending a campaign in Virginia, Cornwallis took post at Yorktown with a force of about 8,000 men. Washington, meanwhile, guarding Clinton's main British force in New York, was joined in April by 4,000 French troops under the Comte de Rochambeau. On 14 August he learned that French Admiral De Grasse, with a powerful fleet, was sailing from the West Indies to the Chesapeake Bay. In the hope of surrounding Cornwallis by land and sea, Washington hurried southward with the main portion of the Franco-American Army, leaving only a small force to guard Clinton in New York.

The plan worked remarkably well. De Grasse arrived in the Chesapeake on 30 August, landed additional French troops, and fought an indecisive battle with the British fleet, but at its end remained in firm control of the bay as the Allied armies arrived. On 28 September these armies began siege operations, using the traditional European system of approaches by parallel trenches. In order to complete the second parallel, Washington ordered the seizure of two British redoubts near the York River. The French were assigned the first, Redoubt No. 9, and the American Light Infantry under Lt. Col. Alexander Hamilton the second, Redoubt No. 10. On the evening of 14 October, as covering fire of shot and shell arched overhead, the Americans and French moved forward. The Americans, with unloaded muskets and fixed bayonets, did not wait for sappers to clear away the abatis, as the French did, but climbed over and through the obstructions. Within ten minutes the garrison of Redoubt No. 10! was overwhelmed. The French also met with success but suffered heavier losses.

After a vain attempt to escape across the York, Cornwallis surrendered his entire force on 19 October 1781, an event that virtually assured American independence, although the final treaty of peace was not signed until 3 September 1783.

Newburgh, May 1783

After his victory over the British at Yorktown, Washington established his headquarter at Newburgh where he could keep a watchful eye on the English forces in New York. He hastened to remind his command that peace was not a foregone conclusion and military readiness must be maintained. Washington also continued his efforts to improve the condition of his troops and insure a high state of morale. One of the ways he decided to accomplish the latter was to create, on 7 August 1782, a "Badge of Military Merit" for enlisted men who had performed bravely in combat.

Two men selected by a board of officers to receive this award were Sergeant Elijah Churchill of the 2nd Continental Light Dragoons and Sergeant William Brown, a member of the 5th Connecticut Regiment, Continental Line. Brown, a veteran of 18, had won praise for his bravery in the storming of Stony Point in 1779 and now was cited for gallantry in the trenches before Yorktown. Churchill had distinguished himself during attacks against two forts on Long Island.

On 3 May 1783, these men left the Continental Cantonment at New Windsor and reported to the nearby headquarters of Washington at the Hasbrouck House in Newburgh. There, before a guard mount of the 1st New York, the Commander-in-Chief awarded Sergeant Churchill (pictured on the right) and Sergeant Brown their badges. Surviving records for the period confirm the presentation of only one other Badge of Military Merit, and the decoration was not used at all after the end of the Revolutionary War. It was revived in February 1932 as the Purple Heart out of respect to Washington's memory and to his military achievements.

The ceremony, however, symbolized much more than recognition of two brave men. It represented the climax of the molding of a citizen army of volunteers and militia into a force that had fought on equal terms with one of the world's best armies, and in doing so, had played a vital role securing freedom and independence for themselves and their fellow citizens.