Army Art Posters and Prints

THE AMERICAN SOLDIER - PRINT SET 5

CMH Pub 70-1-5;

Not Available through GPO sales.

10 full-color 9" X 12 3/4" reproductions of paintings depicting the American Soldier at various periods of our history. Each set includes a booklet describing each print in detail. The following 10 prints are available in print set 5. Individual prints may not be requested.

* View this publication online.

The American Soldier, 1780 - by H. Charles McBarron

Spanish Troops at Pensacola, Florida

Motivated by revenge for lost possessions, Spain, in 1779, joined the French and the infant United States in the war against Great Britain. Although the French were eager to launch combined operations in America, the Spanish refused. Instead, the governor of Louisiana, Gen. Bernardo de Galvez decided to eliminate the British holdings in East and West Florida. As part of his overall operations, forces under his command secured the Mississippi River ports of Manchac, Baton Rouge, and Natchez.

The following year, in 1780, his troops took Mobile and then prepared to crown their successes with the capture of Pensacola, the seat of the British government in West Florida. Brig. John Campbell was in command of the recently completed Fort George and had at his disposal several companies of the 16th and 60th Regiments of Foot, a battalion of "Waldeckers" and two motley battalions of American Loyalists recruited from Maryland and Pennsylvania, a total of nine hundred men.

Although the Spanish landed over eight thousand troops, they were unable to take the well-constructed fort by direct assault and began formal siege operations. Fortunately, a deserter from one of the Loyalist battalions provided to the Spanish artillerymen a good estimate of the range of the principal magazine. A direct hit was scored on 8 May 1780, killing approximately one hundred men and destroying one of the redoubts. Although the follow-up assault ground to a halt amidst the ruins, the presence of Spanish marksmen inside the fort made the serving of the British guns impossible and Campbell surrendered. This campaign relieved pressure on the southern states.

Here, amid the destruction from the exploded Fort George magazine, the painting depicts a grenadier officer of the Louisiana Regiment urging his troops to the assault. The Louisiana Regiment was organized in 1765 and their uniform, consisting of a white coat with blue facings and yellow buttons over a blue vest and breeches, was established at that time. The figure in the red jacket with yellow lace and buttons and blue facings, wearing a low crowned leather cap and white breeches, is from the Company of Free Blacks of Havana.

The American Soldier, 1781 - by H. Charles McBarron

French Troops at Chester, Pennsylvania: Rochambeau and Washington

Sir Henry Clinton, the British commander in chief in North America had long planned to neutralize the state of Virginia by establishing a base in the Chesapeake Bay region, encouraging Tory action in support of the crown, and sending raiding forces up the various rivers. In January 1781 he initiated a devastating raid with sixteen hundred men up the James River under the traitorous Benedict Arnold. To counter or capture Arnold, Washington sent Lafayette to Virginia with twelve hundred Continentals to be augmented by Virginia militia. This effort was not successful. Indeed, after British reinforcements arrived from New York, the raids worsened and, following the late May arrival of General Cornwallis, British strength increased to about seven thousand men. Lafayette then became the pursued. But General Clinton in New York was not enthusiastic about Cornwallis' pursuit in the Virginia interior and ordered him to return to the coast, establish a base, and provide a contingent of troops to New York. Responding, Cornwallis returned to Yorktown by way of the York River. He was warily followed by Lafayette and General Wayne who had joined Lafayette with an additional eight hundred Continentals.

During this period, Washington was negotiating to obtain French cooperation for a combined sea-land attack on New York in the summer of 1781. He was subsequently informed in mid-August that the French West Indies fleet under Admiral de Grasse would not come to New York but would go to Chesapeake Bay and remain there until mid-October. Washington realized that if he could achieve superiority on land while de Grasse blockaded the bay, Cornwallis could be defeated before Clinton could relieve him. His immediate problem was to move as many American troops south as could be spared from the defense of West Point as well as Rochambeau's four thousand French who had joined him in April without raising Clinton's suspicions. It would also be necessary for the French squadron from Newport under Admiral Barras to bring ammunition and supplies to Chesapeake Bay. Finally, and of utmost importance, de Grasse's fleet with its ships and reinforcements had to arrive as planned. To deceive Clinton, Washington deliberately leaked information that ongoing movements of American and French troops were to concentrate for an attack on Staten Island from New Jersey. The ruse was successful. But when word reached Washington in Philadelphia on 1 September that the reinforced British fleet had sailed from New York, he could only conclude that the British fleet was out to intercept Barras or de Grasse.

The American-French force marched through Philadelphia during the next few days and past Chester to the Head of Elk from where they were to be transported by water to Yorktown or an alternate location close by. Washington followed on 5 September by road, while Rochambeau went to Chester by water. Still plagued by his worries regarding the French and British fleets, Washington rode steadfastly past Chester. Three miles to the south he was met by an exhausted express rider who reported that Admiral de Grasse with twenty-eight ships of the line and three thousand men was in Chesapeake Bay.

Washington turned back to Chester to give the exciting news to Rochambeau. When the Frenchman's ship came in sight, the usually dignified Washington took off his hat, waved it around, and laughed and shouted at the astonished French general, who soon joined in the rejoicing.

The painting depicts Washington waving to Rochambeau and shows a group of enlisted men from the French Soissonais Regiment, and an American and a French staff officer. General Washington and the American staff officer wear the black cockade with white center in honor of their French allies, and the French staff officer wears a white cockade with a black center in honor of the Americans.

The American Soldier, 1814 - by H. Charles McBarron

Free Men of Colour and Choctaw Indian Volunteers at New Orleans, Louisianna

While peace negotiations to end the War of 1812 were taking place at Ghent in late 1814, the British decided to continue an operation that had been planned earlier. This was to be a raid upon the Gulf coast to capture New Orleans and possibly separate Louisiana from the United States. The Americans, having received early word of the British intentions, placed their southern defenses under the command of Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson. Jackson arrived at New Orleans on 2 December and began making preparations to meet the British expedition.

The British force, under Major General Keane, made good progress. Arriving at the mouth of Lake Borgne on 10 December, they met and captured the American gunboat flotilla on that lake four days later. After that they conducted an undetected reconnaissance to within six miles of New Orleans.

News of the gunboats' capture caused consternation. Jackson placed the city under martial law and concentrated his scattered troop detachments nearby. General Coffee with his mounted riflemen arrived on 19 December, and Tennessee and Mississippi volunteers, under General Carroll, arrived a few days later. In and around the city itself Jackson had two regular regiments, the 7th and the 44th; a thousand state militia; a battalion of three hundred city volunteers; a rifle company of about sixty; a battalion of free blacks, mostly refugees from Santo Domingo; and twenty-eight Choctaw Indians. It was fortunate that Jackson's men had concentrated quickly, for at noon on 23 December the British advance force, a light brigade of about nineteen hundred men under Lieutenant Colonel Thornton, appeared on the banks of the Mississippi at the Villere plantation about nine miles from New Orleans, where they were to camp for the night. Jackson was told of the British arrival and decided to attack that evening. The main body of about thirteen hundred led by him would make a frontal attack, and Coffee with approximately seven hundred would hit from the flank while the armed schooner Carolina in the river would sweep the British with its guns. The action began well. The Carolina commenced her bombardment at 7:00 p.m. and soon after, Jackson and Coffee engaged the surprised British. But the early winter night had fallen and with the night came fog. Men became separated from their units and soon the action became a melee with squads and individuals meeting, often fighting hand-to-hand with little overall control. At first the Americans were successful, but the British steadied with the arrival of reinforcements. After about an hour and a half of this confusion, Jackson broke off the action and withdrew his troops. He was followed by Coffee an hour later. The Americans lost 213 killed and wounded. British casualties totaled 267.

The painting shows the Choctaws and a mixed group of Major Daquin's Battalion of Free Men of Colour. The latter were mostly attired in civilian clothes because they had been organized only for a few weeks. They are led by an officer distinguishable by his sword and red sash. Facing them are members of the British 85th Regiment in red coats with yellow facings and white lace, and members of the British 95th Regiment in green uniforms with black facings and white lace.

The American Soldier, 1862 - by H. Charles McBarron

The Citizens Corps of Wisconsin at South Mountain, Maryland

With the outbreak of the Civil War in the United States, a number of ethnically-oriented militia groups responded to President Lincoln's call for volunteers to preserve the union. One such unit to volunteer was a predominantly German-American unit known as the Citizens Corps of Milwaukee. On 25 and 27 April 1861, the unit officers, William Lindwurm, Frederick Schumacher, and Werner Von Bachelle were commissioned captain, first lieutenant, and second lieutenant of the company, respectively. By 10 May 1861, the company was officially mustered into the evolving 6th Wisconsin Regiment as Company F, bringing the total of German-Americans in the Union Army to almost thirty-six thousand.

On 16 July 1861, the 6th Wisconsin Volunteers departed for Washington, D.C. Here, the regiment was brigaded with the Union Army's 2d and 7th Wisconsin Regiments and the 19th from Indiana, under Brig. Gen. John Gibbon. The brigade, in 1862, achieved increased efficiency and military prowess and a distinctive uniform that resulted in the nickname "Black Hat Brigade" from fellow Union soldiers. Following the brigade's determined assault upon the heights at Turner's Gap at South Mountain, Maryland, Gibbon's brigade won a new title, "The Iron Brigade of the West". Three days later, the unit proved its worth once again by bravely assaulting Lee's forces in one of the bloodiest battles of the war.

Shown in the painting is the brigade assaulting the Confederate forces at Turner's Gap. The men of the 6th Wisconsin Volunteers are wearing dark blue frock coats with sky-blue trousers. A few are attired in grey overcoats. All are wearing either the black wool/felt hat with a sky-blue double looped cord or Model 1858 forage cap. Armed with the M1861 Springfield muzzle-loading rifle muskets, the men of the Wisconsin units prepare to meet the enemy at the summit.

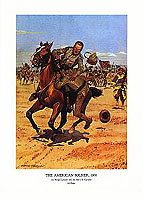

The American Soldier, 1900 - by H. Charles McBarron

1st Bengal Lancers and the 6th U.S. Cavalry in China

The proposed partition of China in the late 1890s by Germany, France, Russia, Japan, Austria, and Italy was viewed by the Chinese as a threat to the integrity of their country. This partition of China into foreign spheres of influence for trade purposes was so strongly opposed by Britain and the United States that the other powers finally agreed to an Open Door Policy. However, the younger Chinese strongly resented western exploitation of their country. They formed a secret society known as the Boxers which was sworn to annihilate foreign influence. By early 1900, Boxers in the northern provinces had killed hundreds of foreigners and Chinese Christians. They then besieged the foreign legations in Peking, guarded by a military and civilian force. In June 1900, a large international relief force of about nineteen thousand troops was formed from contingents provided by Germany, France, Britain, Austria, Russia, Italy, Japan, and the United States to free the legations. The American force under Maj. Gen. Adna R. Chaffee, called the China Relief Expedition, had a strength of about twenty-five hundred men. The relief expedition, including troops from the Philippines as well as the 1st and 3d Squadrons, 6th U. S. Cavalry (shipped directly from the United States), participated in the seizure of Tientsin on 13 July 1900.

By early August most of the allied relief force was committed from Tientsin to relieve the Peking legations, leaving behind, among others, the 6th Cavalry and also some men of the British 1st Bengal Lancers. The troops remaining in Tientsin were to secure the lines of communication and obtain information on Boxer or Chinese Imperial troops in the vicinity. Troop A, 6th Cavalry, under 1st Lt. E. R. Heiberg, "armed with carbines and pistols" was ordered to join a detachment of the 1st Bengal Lancers under Lt. J. R. Gaussen on 15 August for a reconnaissance. The allies were to locate, but not engage, a force of Chinese Imperial troops reported west of Tientsin.

The next morning the combined group left early and, after an uneventful ride of about eight miles, seeing nothing but "undestroyed villages, cornfields, and plowed fields," they came across a village flying red flags, usually a sign of enemy troops. Led by Heiberg and Gaussen, the group moved at a trot in a line of skirmishers with a reserve towards the village. Heiberg then saw what seemed to be two rows of trenches, dismounted carefully to scan them, but again nothing unusual could be seen. The force then advanced to within two hundred yards of the trenches when it came under fire from the front and the right and left flanks. In the confusion the skirmishers retired on the reserve and one of them, Cpl. Rasmus Rasmussen, was thrown from his horse at the point of farthest advance. Heiberg and Gaussen saw Rasmussen lying on the ground near the Chinese trenches. Heiberg's horse became unmanageable, so Gaussen rode on. The Chinese, who had also seen Rasmussen, emerged from their trenches to take him prisoner. The race was on. Lieutenant Gaussen reached Rasmussen first. In Heiberg's words, "Lieutenant Gaussen succeeded in mounting Corporal Rasmussen behind him and rode to the rear. But for the gallant lieutenant, I am quite sure that Rasmussen would have been captured, as he was perhaps less than 250 yards from the trenches, and the enemy had left their trenches after him."

The allied contingent fired dismounted for a short time and then withdrew. They returned home at about 1:00 p.m. "without the loss of a single man or horse." For his bravery during the operations in China, Lieutenant, later Brigadier General, J. R. Gaussen was awarded the China medal with clasp and named Companion of the distinguished Service Order.

The painting shows the moment of Corporal Rasmussen's rescue by Lieutenant Gaussen. Both men are in the khaki uniforms preferred for the relief expedition.

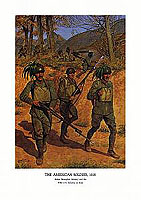

The American Soldier, 1918 - by H. Charles McBarron

Italian Bersaglieri Infantry and the 332d U.S. Infantry in Italy

The 332d Infantry Regiment, 83d Division, together with attached medical and supply units, was, sent to the Italian front in July 1918 in response to urgent requests from the Italian government. Its principal missions were to raise Italian morale and to confuse and disrupt the enemy by creating the impression that a large American force had reached the front and was preparing to participate actively in the fighting in that area.

Trained in the rigors of mountain warfare at its first station near Lake Garda, the regiment proceeded to Treviso and its next assignment with the Italian 31st Division, behind the Piave River. There, for the purpose of deceiving the enemy, the, 332d Infantry staged a series of marches in which each battalion, attired in various uniforms, left the city during daylight and in full view of the Italians and Austrians but later returned inconspicuously by an alternate route at night.

During the Italian Vittorio Veneto offensive, on 29 October, the 332d Infantry formed the advance guard of the British XIV Corps of the Italian Tenth Army as it pursued the Austrians from the Piave to the Tagliamento River. Four days and several marches later, the 332d reestablished contact with the enemy rear guard battalion, engaged them in combat, and overran their position on 4 November 1918. At 3:00 P.M. on that day, the armistice between Italy and Austria-Hungary became effective. Shortly afterward, the American troops were assigned in smaller units for occupation duty. In March 1919, the regiment reassembled in Genoa, prior to embarking for the United States.

Shown in the painting are U.S. Army and Italian Bersaglieri troops as they train in preparation for combat with the Austrians. The soldiers of the 332d Infantry Regiment are armed with the M1903 Springfield rifle and M1905 bayonet and are attired in the standard US Army uniform and equipment of the period. The Bersaglieri are wearing the standard 1909 grey green uniform with steel grey helmets and cockerel feathers and carrying a pistol and a M1891 6.5mm Mannlicher-Carcano rifle and bayonet at the ready.

The American Soldier, 1945 - by H. Charles McBarron

Brazilian Expeditionary Force in Italy

Because of the Brazilian Expeditionary Force (BEF), Brazil had the distinction of being the only Latin American nation whose participation in World War II was represented in division strength. The first Brazilians to fight in Europe were the men of the 6th Regimental Combat Team, committed in Italy on 14 September 1944. Other elements of the BEF followed and were assigned to sectors at the front controlled by the U.S. IV Corps of the Fifth Army.

In 401 days of continuous operation as part of the IV Corps, the Brazilians took part in the liberation of 24,580 square miles of Italian soil, including more than six hundred towns and cities. One of the unit's more memorable engagements was an attack in support of the IV Corps' 10th Mountain Division assigned to take a series of mountain peaks and ridges which had been used by the Germans to observe U.S. troop movements along one of the two main arteries to Bologna and the Fifth Army's front.

Two objectives of the Mountain Division's attack were Riva Ridge and the Monte Belvedere-Monte della Torraccia. Riva Ridge was a cliff that rose almost fifteen hundred feet from the valley floor, all of which had to be scaled prior to gaining access to Monte Belvedere.

Covering on the right, the BEF was to hold a three-mile sector between the Mountain Division's right flank and the Reno River in front of the Fifth Army. During the operation, the BEF seized Monte Castello, about one mile southeast of Monte della Torraccia. Soon after nightfall, on 23 February 1945, the Brazilians assaulted the crest and seized their objective, thereby protecting the Mountain Division's right flank from enemy counterattack.

Featured in this painting are members of the Brazilian Expeditionary Force in the final stages of defeating the enemy on Monte Castello. The men of the BEF are firing an 81-mm mortar and are attired in typical American uniforms of the World War II period: wool trousers, M1943 field jacket, and the modified M1910 individual equipment which included the M1 rifle, Ml carbine, and the M1Al Thompson submachine gun.

The American Soldier, 1945 - by H. Charles McBarron

Philippine Guerrillas in the Liberation of Los Banos, Luzon

Among the many internment camps for civilians set up by the Japanese in the Philippines during World War II was one near the little town of Los Ba�os, forty-two miles southeast of Manila. Here, several miles behind enemy lines and approximately two miles from the southwest shore of Laguna de Bay, on Luzon Island, was the second largest concentration of allied men, women, and children in the Philippines. Represented were ten nationalities whose citizens ranged in age from six months to seventy years. While many were missionaries, nuns, and priests of various orders, a few were U.S. Navy nurses who had been incarcerated since their capture on Corregidor in 1942.

In February 1945, the 11th U.S. Airborne Division and six Philippine guerrilla units operating on Luzon devised a plan to liberate the camp and for that purpose formed the Los Ba�os Task Force under Col. Robert H. Soule. The group consisted of approximately two thousand paratroopers, amphibious tractor battalion units, and ground forces as well as some three hundred guerrillas. The key to the rescue was an assault force consisting of a reinforced airborne company who were to jump on the camp while a reconnaissance force of approximately ninety selected guerrillas, thirty-two U. S. Army enlisted men, and one officer pinned the guards down. The remainder of the force was to launch a diversionary attack, send in amphibious reinforcements, and be prepared to evacuate the internees either overland or across the lake. The bulk of the Philippine guerrillas were to assist by providing guides and marking both the drop zone and beach landing site. This plan was based on intelligence provided by guerrilla observations of the camp guard locations and routines, supplemented by a detailed map of the Los Ba�os Camp which had been drawn by a civilian internee who had managed to escape. The group learned that eighty guards and a well-armed garrison maintained the camp and were backed by eight to fifteen thousand troops who were several hours' march away. Using this information, the reconnaissance force was directed to approach the area by way of Manila and Muntinlupa under cover of darkness on 21-22 February, in preparation for an attack on 23 February.

At dawn, just before the planes were within sight bearing the paratroopers whose chutes would signal the attack, an alert Japanese sentry spotted a guerrilla moving into position and fired a shot to alert the garrison. The attack was forced into motion as a guerrilla wielding a bolo knife quickly silenced the guard, while others in the reconnaissance force killed most of the sentries who remained. By the time the airborne company could join the assault, most of the guards had been either killed or driven from their posts. When the remainder of the parent airborne battalion and pack howitzers arrived by amphibious tractors, the remaining pillboxes were taken and the force turned its attention to the sole reason for the entire mission: the liberation of the 2,147 internees from almost certain death. By 1:30 P.M. that day, the last of the internees, paratroopers, and guerrillas had been evacuated from Los Ba�os. Casualties consisted of three guerrillas killed and six wounded and two U.S. paratroopers killed and four wounded. Apparently, the entire Japanese garrison was killed.

Clearly shown in the painting is a guerrilla armed with a bolo knife divesting a Japanese sentry of his rifle. Crouched behind the foliage and clutching U.S. issued .30 caliber M1903 series rifles, are other members of the force who wait to assist the 11th Airborne force landing in front of the camp.

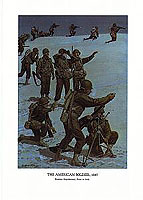

The American Soldier, 1951 - by H. Charles McBarron

Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry at Kap'yong, Korea

After the army of communist North Korea invaded South Korea on 25 June 1950, the United States and other members of the United Nations dispatched land, sea, and air forces to assist the South Koreans in repelling the invasion. Among the first countries to provide assistance was the Dominion of Canada, initially by sending three destroyers to Korean waters and then, in December 1950, by committing the 2d Battalion, Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry. Following some advanced training, the Patricias, commanded by Lt. Col. J. R. Stone, joined combat operations in mid-February 1951 as part of the 27th British Commonwealth Brigade.

On 22 April 1951, Chinese forces which had entered the war in support of North Korea, launched powerful attacks in the western and west-central sectors of Korea toward the South Korea capital city of Seoul. To prevent the enemy from advancing down the Kap'yong River valley and reaching a main road leading to Seoul, the Patricias, together with 3d Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment, and Company A, U.S. 72d Heavy Tank Battalion, occupied defenses blocking the valley. The Patricias dug in on Hill 677 at the western hinge of the defensive position, with the Australians to their right and American tanks in support.

Throughout the day and night of 24 April, two regiments of the Chinese 118th Division attempted to penetrate the Canadian defensive position. Dawn of 25 April found the Patricias still in command on Hill 677, but cut off from the rear by Chinese who had reached the road just behind them. By late afternoon, however, the Chinese force, after having been severely punished by the steadfast Canadians, gave up the battle and withdrew north.

This action prevented an enemy breakthrough and eliminated the threat to Seoul. In recognition of their important victory, the Canadians received the American Distinguished Unit Citation for "gallantry, determination, and esprit de corps in accomplishing their mission," thereby distinguishing "themselves, their homelands, and all freedom-loving nations."

Firing British-made rifles No. 4 Mark 1, and a Bren .303 light machine gun, the Patricias repel the Chinese who threaten their position. The men of the 2d Battalion, Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry, wear the traditional Canadian Army battle dress which includes hooded parkas and caps or "balaklavas."

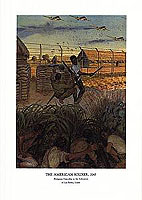

The American Soldier, 1966 - by H. Charles McBarron

Korean Capital (Tiger) Division Phu Cat Mountains, Vietnam

Next to the United States, the nation supplying the most assistance to the Republic of Vietnam was the Republic of Korea. In August 1964, the Korean government responded to a request for allied support in Vietnam and dispatched a number of professionals whose skills ranged from karate to surgery.

Later, in March 1965, Korea committed its first troops in the country. First to be dispatched was an army engineer battalion, followed by combat units designated as the 2d Korean Marine (Blue Dragon) Brigade, the 9th Infantry (White Horse) Division, and the Capital (Tiger) Division.

By mid-1966, these units had assisted the South Vietnamese Army in securing the coastal region of the II Corps Zone by patrolling an area of approximately two hundred and fifty miles between the jungle-covered Phu Cat Mountain region in Binh Dinh Province and the coastal city of Phan Rang in the Ninh Thuan Province. It was during this time that the units earned the respect of both friend and foe alike for their patience and persistent pursuit of the enemy. For their participation in an operation called Maeng Ho 6, the Korean Tiger Division spearheaded a guerrilla-styled campaign against a Viet Cong (VC) terrorist-based sanctuary in the Phu Cat Mountains of South Vietnam. Pursuing the VC from hideout to cavern, the Koreans literally sat out the enemy until he was forced to surrender for lack of the basic necessities of life. With this tactic, the Korean forces drove the enemy from his mountainous sanctuary and rid the some fourteen thousand inhabitants in and around the Phu Cat Mountains of terrorists who had plagued the area since 1954.

Featured in this scene is the final effort in which Korean and U. S. forces converge to clear the mountain area. The Koreans are attired in U.S. Army fatigues, with M1956 individual equipment which includes intrenching tool and cover, pack, ammunition pouch, pistol belt, canteen, canteen cover, first aid packet pouch, and equipment suspenders. They are armed with the Ml rifle with the M5A1 bayonet in the M8A1 scabbard and the M60 machine gun, and are supported by M48 tanks and U. S. Army UH-1C Iroquois helicopters.