CHAPTER XVI

Truck Transport

Construction, assembly, and petroleum operations were vital but secondary parts of the American mission. By directive of the Combined Chiefs of Staff the primary mission was transport. An American trucking service, first proposed in May 1942 by General Somervell, was regarded by the SOS planners as supplementary to existing British trucking organizations.1 It therefore received a priority lower than that accorded to the American organizations for ports and railway. This was not because the planners failed to recognize urgent trucking requirements. The crisis of midsummer 1942 had demonstrated that, until rail capacity in the Corridor could be vastly improved, the only hope of dealing with mounting backlogs of cargo at the ports was to strengthen the existing British motor transport system, as operated by the United Kingdom Commercial Corporation and British military trucking units. The assignment of third priority status to an American trucking organization resulted rather from the long-term view that, since there was no possibility of organizing and shipping a fully functioning American trucking outfit to the Corridor in time to affect the immediate problem that faced the planners in August 1942, it was best to encourage such local assistance to UKCC as was possible while organizing and putting into the field an American motor transport service. American trucks would strengthen the British services. Unlike the American port and rail services, the Motor Transport Service was not to supplant any existing British activity.

In a country of desert and mountain, ill supplied with highways, relatively waterless, and subject to extremes of climate, transport by road was less efficient by all measurements than bulk transport by rail. Furthermore, granting adequate capacity both by road and rail, there would always be cargoes that were not truckable; and granting maximum rail development, the need for truck operations would correspondingly decrease. Planning for a motor transport service was thus subject to greater contradictions and more uncertainties than was

[309]

planning for rail expansion. A trucking organization, even as a temporary expedient, required highways adequate to heavy usage. To this contradiction between permanent highways and temporary planned use were added the basic uncertainties existing at the time the SOS Plan was being evolved. The SOS planners' estimates, which depended on important unknowns such as the routes to be used and the extent to which an American motor transport service was to supplement UKCC operations, were subject to further variables inherent in the nature of truckable cargoes. Estimates relying upon a steady flow of tonnages were at best tentative.

In its provision for trucking the SOS Plan therefore confined itself to a statement of general intentions. Its estimate of required personnel proved accurate enough: 5,291 men for road operations plus an additional 4,515 for highway and vehicle maintenance. Estimates of required vehicles and anticipated targets, on the other hand, were not achieved. The hope of the planners to supply 7,200 trucks of 7-ton average capacity was not realized, and all calculations based upon the use of larger trucks were overturned when the Motor Transport Service found it would have to use whatever vehicles it could get. In the matter of target estimates, the SOS planners were in no position to indicate what proportion of the 172,000 tons of ultimate monthly road capacity it expected the MTS to handle and what proportion was for British agencies, nor could the plan indicate precisely what part of the total it expected to be USSR tonnage. With only the vaguest of maps, MTS launched itself upon a road wrapped in mists and marked by unexpected turnings.

Planning, early organization and procurement, overseas shipment, and early operations were all carried forward under the necessity of adjusting the concepts of the SOS Plan to field realities. On 9 October 1942, shortly after approval of the SOS Plan, Headquarters and Headquarters Company, MTS, was formally activated at Camp Lee, Virginia, with Col. Mark V. Brunson as director. He was assisted by two Regular Army officers and three experienced truck fleet operators and maintenance experts commissioned from civilian life.2

[310]

Personnel estimates called for two truck regiments totaling 3,270 officers and men. This somewhat greater than standard strength allowed for unpredictable operating situations. A minimum of two automotive maintenance battalions-one medium and one heavywas provided for, with a considerable assortment of engineer troops for highway construction and maintenance and for construction of sheds, shops, camps, and other necessary facilities. Recruitment was marked in its first stages by haste and confusion; however, it was distinguished by the effort to obtain from the rank' of experienced trucking men both top experts and the great body of drivers, mechanics, and dispatchers upon whose skill and fortitude hung the ability to throw an organization together in short order. The quartermaster authorities, to whom Headquarters 1616 delegated the trucking problem early in October, appealed to the American Trucking Associations, Inc., at Washington for advice and assistance in speedily assembling adequate numbers of experienced men. In five days the organization, through telegrams to 350 regional members of its Special War Committee who in turn vigorously stimulated enlistments locally through handbills and radio, brought in to the Army from the ranks of the civilian trucking world 5,377 applications for enlisted grades and 263 officer candidates. The response exceeded expectations and was due, in part, to the fact that word got around that the new recruits would be eligible for advanced grades and would be exempt from many features of Army training. When this impression was corrected-as it was promptly-enthusiasm somewhat diminished. Evidence conflicts as to how many men were actually inducted from among the applicants solicited; but the 516th Quartermaster Truck Regiment was largely staffed by officers who had been fleet maintenance men, traffic experts, and specialists in fuel distribution and cargo handling, and manned by experienced dispatchers, drivers, and mechanics. The other regiment called for by the SOS Plan, the 517th, suffered from the reaction which set in among truckmen after the confusion over promises had been cleared up. Its strength was largely composed of assignments and transfers from other troop units in the Army and not of men with specific trucking skills and experience.3

[311]

Step by step the organization took shape. In November Colonel Brunson and three officer assistants arrived by air at Basra to investigate routes and sources of fuel supply; to accept some two hundred trucks turned over by UKCC and .the British Army at Bushire and Tehran; and to plan for establishment of MTS relay stations along the highway from Khorramshahr northward, for schools to train native drivers and mechanics, and for fleet operations. On 17 December the MTS was established as an operating service of the American command.4 When command headquarters moved early in January 1943 to Tehran, MTS moved its headquarters there, too. In December 1942 the 429th Engineer Dump Truck Company and a First Provisional Truck Company, composed of men drawn from other PGSC units in the field, were assigned to MTS. Their first duty was to accept and assemble the trucks received from the British, and to drive administrative vehicles for the three territorial districts of the command. In January 1943 a school for training native civilian driver-interpreterinstructors was opened at Tehran. It turned out some seventy instructors and paved the way for the opening in February of a school at Andimeshk to train native drivers. The start of this enterprise was delayed until the arrival from the United States of Headquarters and Headquarters Company, MTS, from which its staff of instructors was drawn supplemented by graduates of the interpreter school. The roster of MTS was further strengthened in February by the arrival of the 3d Battalion of the 26th Truck Regiment, a Negro outfit destined to join the 517th Truck Regiment when it should complete its training and arrive in the field. In anticipation of the commencement of trucking operations, the 3430th Ordnance Medium Automotive Maintenance Company, an early arrival, was assigned in February to establish and man relay, service, and repair stations along the route from Khorramshahr to Kazvin.

The assembly of men and equipment, the laying out of service stations, and the gathering of data were among the preliminaries that had to be accomplished before regular American trucking service could begin. There were also problems related to the route itself which pressed for early solution. Because of the concentration of American activity at the port of Khorramshahr and the impossibility of manning, fueling, and provisioning more than one route, the highway north from there provided the inevitable route for the MTS. But no part of the highway to Kazvin, in December 1942, was fit for heavy and continuous traffic. The sector from Andimeshk south by the year's end was

[312]

provided with a temporary roadway. Bridges and some road construction had been accomplished on the permanent road; but, thanks to the floods of March 1943 which washed away much of what had been built up to that time, construction of the permanent all-weather, two-lane highway from Khorramshahr to Andimeshk occupied the greater part of 1943. As for the northern sector, where the problem was the improvement of an existing road, the American engineer troops did not begin work until June. They progressed so well, along with companion British forces, that by the end of the year barely fifty miles remained unprovided with a hard surface.

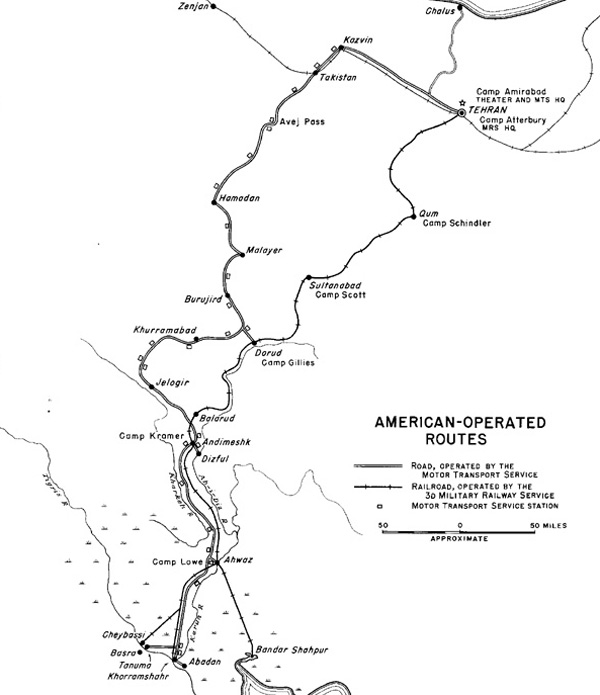

The route from Khorramshahr to Andimeshk crosses a low, sandy plain, varying in elevation from 10 feet at Khorramshahr to 70 feet at Ahwaz and 500 feet at Andimeshk-windy, hot, and dry, swept in summer by dust storms and in winter by heavy rains. (Map 4) The Karun River and the Ab-i-Diz, roughly paralleling the road, run close enough to provide the flood hazard which proved so damaging just as MTS was going into action. Beyond Andimeshk the terrain is characterized by deep gorges and rugged mountains. Some of the ascents are abrupt and steep, occasionally rising as sharply as grades of 10 to 12 percent ( roads in the United States seldom exceed 10 percent). A notable example of this is the Avej Pass (elevation 7,776 feet), the highest point along .the MTS route. Heavy snowdrifts and bitter cold in winter, with temperatures dropping as low as 25 ° F., below zero, proved hazardous features of this 5-mile climbing section of the road.

Along this route, UKCC, which had been hauling Russian-aid, British military, and other cargoes since late 1941, had established a chain of repair and rest stations at Ahwaz, Andimeshk, Khurramabad, Hamadan, and Kazvin, with a northernmost terminus at Tabriz, capital of the province of Azerbaijan, well within the Soviet zone. Plans for a supplementary American trucking service over the same route had assumed the farthest destination. The SOS Plan had stated, "Truck convoys will pass over these routes to Tabriz, Pahlevi, and other delivery points to the Russians," and Colonel Brunson's January 1943 plan for operations listed Tabriz as the destination of first priority, with Chalus and Pahlevi, on the Caspian, following-all of them inside the Soviet zone. This understanding was confirmed in conference on 16 January with the Soviet liaison officer for lend-lease shipments, Colonel Zorin.5

Developments in February threw into doubt the several termini for American operations. The Soviets refused to issue passes to Ameri-

[313]

MAP 4

[314]

can soldier-drivers and workers and notified General Connolly that special application and arrangements would have to be made for sites for American camps near Tabriz, Zenjan, and the Caspian ports. Such applications, promptly made, went unanswered. Suspecting that the difficulty may have arisen from a conflict of overlapping Soviet jurisdictions, Connolly appealed to General Faymonville at Moscow for help and warned that if the destinations planned for were not available, MTS cargo would have to be dumped at Kazvin, on the border of the Soviet zone, to be carried forward from there by the Soviet forces. On 19 February, no change having taken place in the situation, General Connolly wrote to Gen. Anatoli N. Korolyev, Chief of the Soviet Transportation Department in Iran, that all movement orders to American troops beyond the zonal border had been revoked. By 1 March Kazvin was agreed upon as the delivery point for MTS cargoes and, despite a change of mind by the Soviets within a week, when they again suggested that the Americans deliver cargo to the Caspian ports and Tabriz, Connolly held his ground and so reported to the American Embassy, Moscow, and to General Marshall. Although the Soviets made a specific request in June for delivery of cargo at Pahlevi, Kazvin remained the American terminus with the exception of a brief period between September and November 1944 when special MTS convoys, equipped with their own radio communications, went through to Tabriz. The situation recalls the similar uncertainty of Soviet policy in the matter of the terminal checkup stations which were a part of the system for delivering assembled motor vehicles.6

Meanwhile in January an understanding was reached with the British on the gradual meshing of the new American trucking operation with the existing services of UKCC. At a meeting attended by General Connolly for PGSC, General Selby of GHQ, PAI Force, and R. H. Evans, Managing Director of UKCC, it was agreed that by 1 March a small American fleet could be assembled and manned to begin trucking as far south as the condition of the road permitted and to continue to whatever northern terminus was being used at that date. Pending the time when sufficient men and vehicles would permit full-scale MTS operations, the Americans would act as unpaid contractors for the UKCC fleet and UKCC would make no demand upon the USSR for

[315]

payment for carrying goods by MTS trucks.7 The MTS would use UKCC and British military staging camp facilities and services along the road and was to be responsible for guarding its vehicles and for supervising their loading and unloading, while UKCC would arrange for loading and unloading and would perform all accounting. It was further agreed that when MTS went into full-scale operation on its own, UKCC would transfer its facilities at Andimeshk and appropriate adjustments in traffic control of the highway would be made. From then onward, during a period of anticipated rising tonnage, UKCC would serve as an unpaid contractor to MTS. This last provision did not become effective. Concerning lend-lease vehicles, parts, equipment, and supplies there was some disagreement. The Americans proposed that as these had been allocated to the British for transporting F.ussianaid cargo and since that function was being assumed by the Americans ah such equipment as was in storage, en route, or on order should be consigned to PGSC for proper allocation, General Selby disagreed, stating that he understood allocations would be made by the British in consultation with the Americans. The maturing of MTS as an operating agency of PGSC eventually eliminated occasion for disagreement on this point.8

Although there was a small amount of loading activity in late February, MTS operations began officially on 1 March when some 400 trucks started moving Russian-aid cargo out of Andimeshk. The road south of there was not yet usable for regular service. Inasmuch as the 516th Truck Regiment did not reach the field until May, the 517th until July, and other increments of strength and equipment until November, early operations were on a small scale. Available MTS manpower was supplemented by drawing upon other PGSC units; and as MTS strength, before May, was heavier in mechanics and maintenance men than in drivers, these categories were called upon for duty in both capacities. The small fleet of trucks grew by fall to about 2,500 vehicles, reaching by September 1944 a total somewhat in excess of 6,000. Smaller than the fleet projected in the SOS Plan, the total nevertheless

[316]

proved adequate for the shorter route actually used in MTS operations. The first trucks out of Andimeshk drove as a closed convoy to Kazvin, arriving on 4 March. They were followed by daily departures; but the month's score in Russian-aid cargo came to only 3,570 long tons. (Table 6, Appendix A ) Whether the score was high depended on how much truckable cargo was available and what MTS capacity was at the time-both being unknown quantities. Perhaps it should have been higher; in any case, March conspired to demonstrate in one compact lesson many of the problems that would have to be solved before MTS could make a significant contribution to inland clearance. The weather was unusually severe and Avej Pass was closed to traffic for one week of the month. It was to be months before systematic road improvement and maintenance north of Andimeshk started and the road was therefore a hazard in itself; for the rest of the early story, the word inadequate covers the numbers of men available for driving, maintenance, loading, and unloading and characterizes supply and security measures taken against pilferage of cargo.

General Connolly was not satisfied with the share of the inland clearance burden being borne by MTS and felt that tighter organization, improved operating methods, and more vigorous command could make better headway against the many handicaps so apparent in early March. It had been expected that, until the railway attained maximum capacity, trucking would play a large part in taking cargoes away from the ports, and, as the figures show, MTS tonnages through March 1943 were small. Accordingly, Connolly suddenly asked Colonel Shingler to take over MTS on 13 March. Shingler was tested by long experience in the area. He had come out in 1941 with Wheeler, succeeded to the command of the Iranian Mission on Wheeler's departure for India, and had served as commanding officer of the successor organizations until Connolly's appointment late in 1942. He then acted as chief of staff until General Scott's arrival in November. Next month Connolly put Shingler in command of Basra District, with jurisdiction over the critical early operations at the ports. Experience qualified Shingler as a number one trouble shooter. The task he assumed was both delicate and critical, for MTS was largely staffed with professional truckers from civilian life and military transportation experts. His most important contribution to increased MTS performance was the prompt introduction of the block system of dispatching vehicles, noticed later. He also instituted changes in truck servicing at transfer points and devised more expeditious methods of loading and unloading. The immediate result was doubled tonnage for April, and a score for September, the last month of Shingler's service, nearly seven times

[317]

that of March. Methods of trucking developed by him in the Persian Corridor were effectively used in Europe in 1944 in connection with the Red Ball Express.9

The administrative organization of MTS early assumed the basic form which, despite minor changes, was to continue to the end. The effort to distinguish functions as administrative and operational resulted at the start in an arrangement whereby serving under the director were an executive officer in charge of Administration and Supply Divisions and a manager in charge of Operations and Maintenance Divisions. This continued until Col. Glenn R. Ward, who had been manager, was elevated to the post of director and combined in himself both the administrative and operational functions of command. A fifth staff division, called Training, appeared in the March 1943 organization chart. It was charged with training both military and civilian drivers. The November 1943 chart shows this function, as regards military training, transferred to the Administration Division. A new division, for civilian personnel, handled all matters pertaining to the recruiting, training, pay, and administration of native employees. At MTS headquarters at Tehran branches for investigation, traffic control, accident prevention, and statistical analysis and compilation (a function different from documentation, which was performed within the Operations Division of MTS ) were in November 1943 directly tributary to the office of the MTS executive. Later they were absorbed into the staff divisions.10

Provision was made in the earliest organization plans for field stations along the highway. These were to furnish necessary services, and as time went on they took on similar characteristics and functions, each being provided with a refueling point, grease pits, tool room, battery recharging unit, storage rooms, open sheds with bays for second and third echelon maintenance and repair, and accommodations to feed and house the drivers. Some of these functions were of a housekeeping nature and were exercised by the district commanders of the three territorial districts. Others, especially such as were uniquely applicable to a motor transport service (the provision, for example, of fuel oil, lubricants, and gasoline), became the specific responsibility of MTS. Field services were consolidated in time by the division of the

[318]

highway route into two sectors designated as the Northern Divisionfrom Kazvin south to Khurramabad; and the Southern Divisionfrom Khurramabad to Khorramshahr. In October 1943, after the arrival of nearly all troops assigned to MTS, a rearrangement of stations brought all units of the 516th Truck Regiment into the Northern Division and placed all units of the 517th in the Southern Division. The respective division commanders, who were the regimental commanders, were responsible to the director of MTS for operation, maintenance, traffic control, cargo handling, supply, administration, discipline, and housekeeping in their divisions. The Northern Division functioned through main field stations at Khurramabad, Hamadan, and Kazvin, and minor stations at Burujird and Avej; the Southern Division maintained principal stations at Khorramshahr, Ahwaz, and Andimeshk, and a minor station at Jelogir. A separate office for an MTS port officer was at Khorramshahr.11

On the administrative side MTS developed, as an expression of its special operating function, not only a semiautonomy in supply which distinguished it from the other operating services of the command but also virtual autonomy ( always within the limits governed by paramount British responsibilities) in security and related matters. After MTS began its regular trucking operations but before it was clear just what would be its eventual responsibilities in control of the highway route, its director proposed that all the military police in the command be assigned to MTS for use in traffic regulation. Half of the military police in the command, constituting B and D Companies of the 727th Military Police Battalion, were assigned to MTS and were placed under a command so all-embracing that the provost marshal was later forced to take steps to prevent use of MP's as truck drivers at times when MTS manpower was inadequate and desperate measures were called for to meet assigned targets.12 The duties of MP's thus placed under MTS command were defined and their activities regulated by MTS.

Security, in the sense in which the word had meaning for MTS operations, covered several important aspects of the motor transport

[319]

mission. Fundamentally, it included the execution and enforcement of regulations established for the dispatch and movement of MTS vehicles; and, while there was no American responsibility for over-all security, MTS, by Anglo-American agreement, had to look out for its own property and the safety of its own troops and employees. The MP's, who were spread out from eleven police stations up and down the line of traffic-Company B within the Southern Division; Company D, the Northern-had therefore not only to keep traffic moving but to check individual trucks and drivers, to enforce rules for speed, disstance, stopping, and starting, to prevent and to investigate accidents, to deal with pilferage, and to detect illegal haulage of cargo and passengers.

Full American control of the highway came slowly, following American responsibility for road maintenance and the steps by which UKCC reduced its own activity over the route. In fact, except for developments in operational procedures such as loading and unloading and highway and vehicle maintenance, nearly all the mileposts in the MTS story mark decisions and policies which can be related to the primary problem of traffic control-the dispatch and movement of trucks.

Two methods of dispatching MTS trucks were used. For the first four weeks they proceeded in normal military convoy units; but, as the shortage of trucks was greater than the shortage of drivers, this method, which entailed taking trucks through to destination with one driver, left trucks standing idle while drivers were resting. A secondary disadvantage arose from the climatic changes through which the route passed. A driver starting at the desert end in thin clothing met with snow and freezing weather north of Andimeshk and either proceeded with inadequate protection or had to stop to change, thus delaying the run.

On 28 March Colonel Shingler introduced the block system. The route was divided into four blocks with an MTS camp at the end of each-at Andimeshk, Khurramabad, Hamadan, and Kazvin-the four blocks requiring respectively 8, 12, 12, and 8 hours' running time. Under the block system drivers operated out of home stations, taking their trucks to the next station where they handed them over to the driver on the next block. After a rest period of a day or overnight, the drivers drove empty southbound trucks back to their home stations. Vehicles could thus be operated night and day, with time out only for servicing and maintenance. At the terminals of the route, schedules permitted time for thorough overhaul before redispatch of vehicles. Having served during the heaviest period of hauling activity, the block system was replaced on 28 August 1944 by the convoy system. In effectiveness there was little to choose between the two methods, given

[320]

the same number and type of trucks and equal resources in manpower. With limited equipment but ample personnel, on the one hand, the block system, permitting round-the-clock operation, was the more expeditious. On the other hand, the normal military convoy system required less elaborate station operations and smaller maintenance plants manned with fewer service men and, since the driver was responsible for his truck and cargo the full length of the trip, checking of cargoes at transfer points and need for precautions against pilferage were reduced.

The control of traffic passed through several phases. For some time Gulf and Desert District commanders were responsible for the control of MTS convoys south of Andimeshk, but exercised no responsibility for the other users of the road-Iranian civil and military vehicles, Russian soldiers driving trucks north from the Khorramshahr Truck Assembly Plant, and British vehicles under the control of the British Army, UKCC, and AIOC. In July, UKCC, having previously transferred its large rail-to-truck transfer installation at Andimeshk to MTS,13 rerouted its heaviest traffic westward to the Khanaqin Lift, thus relieving the Khorramshahr-Andimeshk leg of the highway of a considerable burden as well as the section between Andimeshk and Ramadan. But at Ramadan the British trucks from Khanaqin and Kermanshah rejoined the American route and proceeded thence to Kazvin and beyond. Especially during the rest of 1943, when the whole length of the route from Khorramshahr to Kazvin was still under construction and repair, congestion continued. American traffic beyond Andimeshk had for some time been regulated by the MP's assigned to MTS; but, although an international Highway Traffic Committee met periodically to consult on traffic problems, no unified control-save that nominally provided by British security authorities-existed.

Congestion was not the only road hazard nor the only cause for delays and difficulties. Truck drivers were not experienced in military traffic procedures and had to be trained while operations continued. Military police were at the start inadequately trained. There were reports in April 1943 that some American drivers held to the center of the road to prevent others from passing; that Russian convoys were disregarding one-way traffic control and going through to the confusion of others; and that Russian vehicles parked in the middle of the road for repairs and rest. Many of the Soviet convoy trucks were driven by soldiers recuperating from battle wounds, assigned to the Persian

[321]

Corridor for a kind of holiday and making the trip for the first and only time over unfamiliar terrain. Native drivers of UKCC, MTS, and Iranian vehicles posed numerous problems. To centralize control it was therefore agreed that MTS should regulate traffic using the highway between Khorramshahr and Takistan, twenty miles south of Kazvincivil and military, American, British, Iranian, and Soviet.14

The first fruit of the new responsibility was the introduction in September 1943 of a system of time bands to minimize congestion and to give necessary priority to MTS convoys, which in that month began a quick rise in delivered tonnage that was to attain in December the highest all-cargo and the second highest Russian-aid total achieved in the life of the service. Each hauling agency using the road was allotted specific hours of the day ( time bands) during which its trucks were assured operating priority on certain sectors of the road. Outside the proper bands, the movement of as many as ten vehicles in any 24-hour period was permitted without restriction. MTS received two 5-hour bands per day in each direction when it had priority. Within each of the four time bands-two north and two south each day-MTS trucks moved in serials containing from twenty-five to thirty-four trucks each. Midway stations were established in all blocks where trucks were fueled, the oil checked, and the drivers given rest and food. In the southern area water stops were set up along the way. After eight to twelve hours of driving time trucks stopped for checkup and relief drivers took over.

The equitable sharing of the road among manly users was an important accomplishment. It proved easier to bring about than the solution of such problems as training native drivers, reducing the rate of accidents, preventing pilferage, establishing communications, overcoming shortages in men and machines, and maintaining personnel and equipment in good working order.

The provost marshal of the command has stated that the program for training native drivers "reflects great credit" upon the MTS.15 The condition of driver shortages was chronic with the MTS until well past the middle of 1943, and in times of special stress there were never enough military drivers to meet emergency increases in tonnages. To deal with the problem, mechanics, clerks, and even MP's were summoned to duty from time to time; men with only four hours' rest were

[322]

sent back to the road; and men unfamiliar with the road or, for that matter, with driving great trucks or responding to convoy signals were pressed into service. The number of soldiers was limited; and therefore, very early, a systematic program was undertaken for training natives. The shift in March from the convoy to the block system called for increased overhead and station personnel months before the scheduled arrival of the first truck regiment from the United States could supply them.

A drive to recruit 3,500 natives as mechanics and drivers, begun in January 1943, was supplemented in that month by establishment of the school at Tehran to train driver-interpreters. Its seventy graduates furnished a pool of instructors for the three drivers' schools, the first of them opened at Andimeshk in February, followed by others at Ramadan and Kazvin. A supplementary diesel school held for specially selected drivers in December 1943 produced 800 qualified drivers. When it is realized that the pupils in these schools had most of them never ridden in a motor vehicle, that their instruction originated in English, that the American instructors did not understand and could not correct what their native interpreters said to the pupils, the difficulty of turning out skilled drivers and mechanics can be appreciated. Then, too, although there was plain bad driving among all nationalities using the road, the natives supplied a fancy variety of their own: Moslem fatalism which accepted the crash that followed rounding a sharp curve on the wrong side of the road as the will of Allah; or the instinct that met the discovery at the top of a steep hill that the brakes had ceased to function by leaping from the cab and letting the burdened truck careen to its destruction and the endangerment of all else on the road. There were also the handicaps imposed by widespread opium addiction. The reports are in agreement that after training the skill and competence of the native drivers for MTS were of high quality, a tribute to their intelligence and spirit as well as to their instruction.16

The drivers' schools enrolled by the end of July 1944 approximately 16,566 natives and graduated 7,546.17 Yet maximum native driver employment, reached in February 1944, was only 3,155. The relatively

[323]

small numbers of graduates and the small total of surviving drivers in service require interpretation. The figures reflect not only the winnowing process of training but other factors in the general employment situation. Particularly during the early days of the training program it was widely felt by the Americans in charge that irresistible temptation was offered the natives both during and after training to leave MTS. It was said, for example, that drivers working for the Soviet services were not forbidden when piloting deadheading vehicles to pick up passengers and cargo on the side and to pocket the resultant baksheesh. This made working for the Soviet agencies more attractive, inasmuch as the highest wage paid MTS drivers in the early months was 1,800 rials per month, as contrasted to reported scales paid by the Russians and UKCC ranging from 2,500 to 5,000 rials per month. The student wage at the MTS schools of 20 rials a month, plus shelter and a food ration not widely appreciated, tempted students to leave the schools and seek employment elsewhere.

MTS raised the student wage to a range between 450 and 750 rials per month; but at a conference held in May 1943 by representatives of MTS, AIOC, UKCC, and the British and Soviet Armies, the Soviets declined to standardize wage scales. Agreement was reached, however, on more stringent inspections of cargoes to prevent the carrying of unauthorized passengers and loads, and the suggestion was advanced that a system of controlling the movement of drivers from one agency to another be instituted. These measures did not prevent the dissipation of MTS-trained native drivers into other Allied services.18

The course of the civilian-driver training program as well as the accumulation of experience by MTS personnel can be traced in the fluctuating rate of accidents per million truck miles. During April 1943 the rate was computed at 24.9 with nine deaths, eight of them civilian. Overworking of drivers to attain targets; excessive speeding which reflected insufficient MP strength to patrol the roads, as well as inadequate road signs at that early date; heavy dust conditions in the south; and the poor condition of the highway were contributing factors. During the period from July to November the number of civilian (native) drivers rose above seven hundred and the urgency of target requirements made it necessary to place most of them on the road straight from their training courses without enough supervised road experience. The accident rate rose in November to 103 per million truck miles. An intensive safety campaign was inaugurated in December, accompanied by incentives such as certificates granted civilians

[324]

for 10,000 miles of accident-free driving and War Department awards for soldiers. Trips to Cairo and the Holy Land rewarded the soldiers with the best records, and a white elephant emblem was presented each month to trucking companies with the worst records. The decline in accidents which followed reached its lowest rate, 6.7 per million truck miles, in October 1944. In general, soldier-driver accidents during 1944 were caused by mechanical defects, speeding, and driving at improper intervals, while the highest percentage of native-driver accidents resulted from loss of control of the vehicle, driving at improper intervals, driving in the wrong lane, and speeding.

The hard-pressed MP's on patrol were never free from security problems, of which the block system of operation posed that of checking cargoes at the points where one driver handed over to the next. It was usually impossible to make a thorough check until the end of the line was reached. By that time native bandits and pilferers had done their work, aided by sharp turns and steep inclines in the road which forced drivers to slow down, permitting the thieves to drop from overhanging banks in the mountainous sections upon the slowly moving trucks, slit tarpaulins, and throw off items like tires, ammunition, sugar, flour, beans, and cloth. Sometimes pilferage was accomplished by native drivers who succeeded in making their way out of a serial to points off the road where they unloaded. At night cargo was sometimes hurled from the trucks to waiting confederates. Native huts in which to store the plunder sprang up along the route, but these were all eventually burned. In December 1943 continued losses of cargo and equipment led to the assignment of special investigators. Cargo was checked thoroughly at each station before drivers were released, loads were sealed, and the system of waybilling at points of origin was improved; but loss through pilferage was never eliminated.

The dependence of traffic and security controls upon signal communications was early recognized. By December 1942 radio stations at Khorramshahr, Ahwaz, and Andimeshk were available for MTS uses and by April 1943 additional stations at Khurramabad, Hamadan, and Kazvin, the last named being a mobile set, were in service. In May 1943 the MTS requested the Signal Service to plan, install, and operate a radio system for its own use so that communication would be available from one division point to another. Two nets were set up with a maximum of one relay from any one point to another along the entire supply line. Small semifixed stations, installed at intervals between the larger fixed stations, served in emergencies for sudden calls for wreckers and ambulances and for security purposes. In addition, telephone service between Tehran and Kazvin was established. After the completion of

[325]

the teletype network for the command in January and February 1944, the lessening need for radio warranted the removal of the stations at Khorramshahr, Ahwaz, and Andimeshk. Eventually radio service was entirely supplanted by teletype and telephone.

Maintenance of vehicles was a never ceasing problem. At the beginning of operations, when parts and servicing apparatus were in drastically short supply, maintenance difficulties were aggravated by lack of buildings and lighting for the bulk of the work, which had to be done at night. Then, as the end of 1943 saw the virtual completion of the building program and as the shortage of parts gave way to better supply, the growth of the fleet, coupled with the increase-through the aging of vehicles in constant and hard use-of the rate of obsolescence, meant that the work of the indispensable mechanics and repair men was never done. In February 1944 the number of deadlined vehicles for which no parts were available was mounting despite every effort to improvise, repair, manufacture, and reuse parts. Deadlined trucks were systematically cannibalized to keep as many others in service as possible. At the same time truck companies in the north reported being handicapped by lack of proper winter equipment such as skid chains of the right sizes, antifreeze, and windshield wipers and curtains.19 By the end of July roughly 10 percent of the fleet was deadlined-over six hundred trucks; but the reduction of the number to ninety-seven by the end of October illustrates the extremes of crisis to which maintenance was subjected by the uncertainties and vagaries of truck operations in the Corridor as well as the ability of the untiring maintenance troops to meet the crises.

Of the trucks in the MTS fleet, certain types of Internationals, Studebakers, and Mack diesels, none of them specifically designed for the peculiar conditions of Corridor operation, bore the chief burden of the load. It was reported that, all factors considered, the Studebaker 6 x 4 tractor with 7-ton trailer and the 2 /2-ton cargo trucks gave good service.20 It was stated that these vehicles could cover 50,000 miles before repair became uneconomical. Generally, the basic chassis developed only a few serious faults: the cabs, fenders, hoods, dust skirts, and other sheet metal parts failed rapidly, and other failures occurred on hood side panels, hood tops, transmission cover plates, radiator cores, storage battery supports, fan belts, and distributor caps. Studebaker 1-ton trailer mortality was high, largely as a result of abuse when

[326]

operated empty. Tarpaulins required frequent repair. The Mack diesel 10-ton 6 x 4 cargo trucks were considered well adapted to MTS needs. They were good for 100,000 miles before repairs became uneconomical. Parts consumption was low and failures infrequent, but their bodies were too small and were structurally weak. Mack weaknesses were in the radiator, cowl, starter switches, series parallel switches, flexible fuel lines, fuses, and air cleaners. Most diesel road failures were caused by clogged fuel lines. On the basis of experience in MTS, it was felt that the ideal truck would have been a 6 x 4 tractor-trailer diesel with air brakes and a 150-horsepower engine, ten forward speeds, a maximum speed of forty-five miles per hour, power to carry its net load of fifteen tons up 15-percent grades, and stamina enough to operate 100,000 miles over mountainous roads. The trailer would have had a dual axle with air brakes and a van type of body 28 feet long, 7 feet high, and 8 feet wide. But there was no time, in setting up the MTS, to design and produce the perfect truck for the job. It was a supplementary service with a limited life to live and it made the best of available equipment.

It was not only the trucks that took a beating on the highways of Iran. Morbidity studies of the Army personnel of MTS reveal one ailment peculiar to them. Until the entire route was hard surfaced, driving was an ordeal regardless of the weather. Mile after mile of washboard roads took toll of men as well as vehicles. As an anonymous military scribe put it, vibration "shook the trucks to pieces . . . and pounded the men's kidneys to jelly."21 A medical survey in late 1944 of low-back injuries throughout the command during the previous twenty months laid special emphasis on the extent of such complaints among the truck drivers. It was found that of the 466 cases in the command requiring hospitalization one third of the whole were truck drivers who constituted only one tenth of the strength of the command. Rough roads, hard, uncomfortable seats, lack of drivers' belts as supports (these were not included in the Tables of Equipment of truck companies sent into the field), long hours of driving without sufficient rest, army cots which sagged, failure of drivers to seek proper massage and heat for tired back muscles, neglect in reporting for medical care until symptoms were severe, and vehicle accidents were listed as the causes. In other respects, the health of the men did not differ from the average in the command.22

[327]

According to plan, as soon as the ISR demonstrated its ability to serve adequately as the sole agency for inland clearance of Russianaid cargoes, the MTS would be dispensed with. Washington's decision in November 1944 to close out MTS promptly served notice that, in Washington's view, regardless of the remaining course of the war, the railway would be adequate for all demands to come. MTS ceased operations on 30 November 1944.

Comparison of the tonnage accomplishments of the railway and MTS will show clearly why road transport was the first to go and why it went when it did. (Tables 5 and 6, Appendix A) Through 1943 MTS haulage of Russian-aid cargoes steadily mounted. In May the condition of the highway was such that it was possible to begin loading both at the Russian Dump at Khorramshahr and at dockside. Rail-to-truck loadings continued as a regular procedure at Andimeshk until August, after which time loadings there were resorted to only when there was a shortage of truckable cargo at Khorramshahr. How desperately the organization worked to meet the targets set for it at Tehran has been shown by references already made to overworked and inexperienced men being pressed into service as drivers. The July delivery of 17,068 long tons of Russian-aid cargo exceeded by 14 percent the target for that month, the highest set up to that time. Month after month the target continued to be met or exceeded. It was not until January 1944, in a month when truckable cargo at the port proved less than expected by the target makers and when driving through swirling clouds of snow in the treacherous twistings of the mountain highway slowed progress, that, for the first time, MTS failed to reach its target. January's score of 32,385 long tons of Russian-aid cargo fell under expectations by 5 percent. In February the target was slashed drastically and MTS exceeded it by 4 percent. With an interlude of high demand for movement in March, cargoes again fell steeply in April and May to rise in July to the peak for Soviet deliveries. That was the feverish month when the whole command, being challenged by maximum pressures of tonnages, not only rose to them but exceeded them all along the line. After July MTS' share of tonnage was reduced, first gradually, then precipitately, while the railway was pressed to achieve its peak Russian-aid haulage in September. In that month, while the trucks were hauling 8,187 tons for delivery to the USSR, the railway carried 170,100.

When MTS shut up shop and added up its performance, the total of all cargoes carried came to 618,946 long tons. Two thirds of this,

[328]

or 408,460 long tons, were carried for the Russians. The total, while small relative to command totals, was no drop in the bucket. To accommodate what the men of MTS and their native co-workers delivered to Soviet receiving points would have required a line of standard U.S. Army 2 /2-ton 6 x 6 cargo trucks standing bumper to bumper all the way from Baltimore to Chicago.

As was the case with nearly everything the American Army undertook to do in the Persian Corridor, the establishment of a truck service under the conditions met by MTS was without exact precedent or parallel. There is therefore nothing by which to measure MTS achievement. Even UKCC, being an agency of government endowed with the privileges and characteristics of a private corporation (including those of charging for certain services) is not strictly comparable to MTS. Moreover, since UKCC operated trucking services over many routes in Iran and Iraq from late 1941 until long after MTS' dissolution, and since available performance figures do not break down UKCC's totals into time periods or by routes served, there is no common denominator.23

The record of MTS must stand, then, on its own, as a supplementary part of the total Anglo-American program, which in its brief span of activity shouldered something like one tenth of the total American share of Russian-aid deliveries. If the progress of the war and operating conditions in the Persian Corridor had only proceeded in accordance with sound and logical business principles, it could be concluded that the effort, the expense of spirit, treasure, and skill that went into the organization and operation of MTS were not, bookkeeping-wise, commensurate with the proportionate results attained. But a realistic appraisal must conclude that, in spite of its slow start-conditioned by the state of the highway and by the priority which assigned to the railway and ports the paramount considerations of time, manpower, and equipment-MTS was on hand to deliver the goods at a time when, if there had been no American trucks, cargoes would have

[329]

accumulated unmanageably at the ports. As a reserve supply line in case of sabotage on the railway it was indispensable. Its effort must be judged not by its cost in men and equipment, not by its relative contribution to the total logistic achievement, but by the fact that MTS manned the breach when no other means were available to meet a pressing urgency.