CHAPTER XIII

"DOWNFALL" THE PLAN FOR THE INVASION OF JAPAN

While the war was being fought in the Philippines and Okinawa, plans were ripening rapidly for the largest amphibious operation in the history of warfare. "Downfall," the grand plan for the invasion of Japan, contemplated a gargantuan blow against the islands of Kyushu and Honshu, using the entire available combined resources of the army, navy, and air forces.

The plans for "Downfall" were first developed early in 1945 by the Combined Chiefs of Staff at the Argonaut Conference held on the tiny island of Malta in the Mediterranean. On 9 February, just a few days before the historic Three-Power meeting at Yalta, President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill were informed of the conclusions reached at Argonaut. At that time, the strategic concept of future operations in the Pacific embodied the defeat of Japan within eighteen months after Germany's surrender and included the following series of proposed objectives:

a. Following the Okinawa operation, to seize additional positions to intensify the blockade air bombardment of Japan in order to create a situation favorable to:

b. An assault on Kyushu for the purpose of further reducing Japanese capabilities by containing and destroying major enemy forces and further intensifying the blockade and air bombardment in order to establish a tactical condition favorable to:

c. The decisive invasion of the industrial heart of Japan through the Tokyo Plain.1

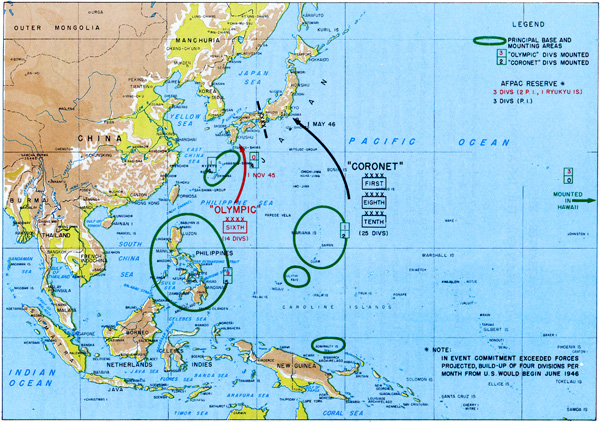

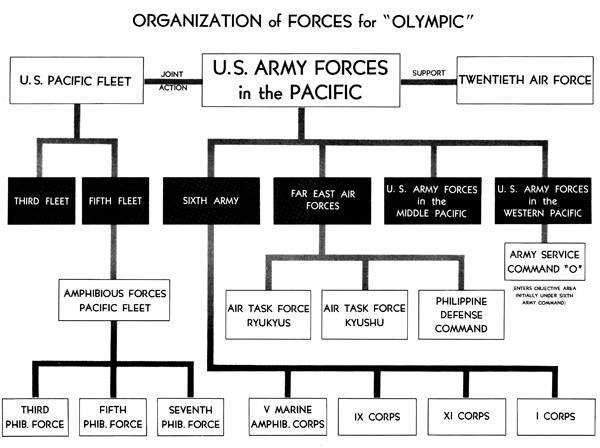

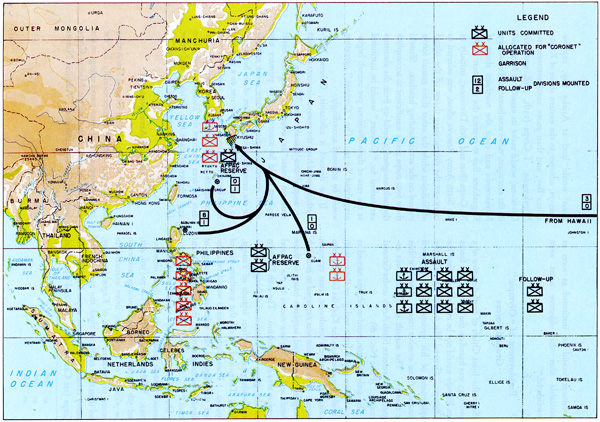

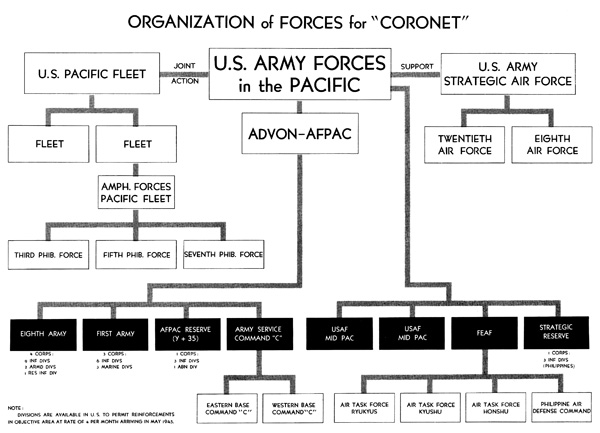

On 29 March, the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, working on the assumptions that the war in Europe would be over by 1 July 1945 and that the forthcoming Okinawa operation would be concluded by mid-August of 1945, set a tentative schedule for the invasion of Japan. The invasion plan was assigned the cover name "Downfall" and consisted of two main operations: "Olympic," the preliminary assault on the southern island of Kyushu, which was slated for 1 December 1945, and "Coronet," the subsequent landing on Honshu, which was scheduled for 1 March 1946. (Plate No. 112) It was proposed that forces already in the Pacific be used to the fullest extent possible in planning for the assault and follow-up phases of "Olympic." Reserve and follow-up divisions for "Coronet" would be obtained by redeployment, either directly or via the United States, of troops and equipment from the European Theater.2

On 3 April 1945, the Joint Chiefs of Staff issued a directive in which General MacArthur was instructed to complete the necessary operations in Luzon and the rest of the Philippines, prepare for the occupation of North Borneo, and "make plans and preparations for the campaign in Japan." The amphibious and aerial phases of the projected Homeland invasion

[395]

PLATE NO. 112

"Downfall" Plan for the Invasion of Japan, 28 May 1945

[396]

were to be formulated in co-operation with Admiral Nimitz and General Arnold.3

Strategies under Consideration

As was to be expected in the consideration of an assault of such magnitude, there were numerous and varying opinions as to the best strategy to follow in developing the final plans. These different opinions flowed into two main channels of thought. On the one hand, it was felt that much more preparation was needed than would be possible under the tentative target dates of 1 December and 1 March for the Kyushu and the Honshu operations. To reduce the risks inherent in any assault on the well fortified and strongly garrisoned islands of Japan, a preliminary and far-reaching campaign of air-sea blockade and bombardment was advocated. To implement such a concept, prior operations along the China coast at Chosan and Shantung, in Korea, and in the Tsushima Strait area were envisaged. Such a strategy, it was held, though admittedly more prolonged than direct assault, would minimize the number of casualties, further reduce hostile air potential, and cut off reinforcements from Asia to Japan. Furthermore, it was conceivable that such a program could force Japan's surrender without the necessity of a major landing on the Home Islands.

The other school of thought believed in driving directly to the heart of Japan as soon as the necessary forces could be mounted from the Philippines and land-based planes could be established in the Ryukyus. The proponents of this strategy contended that Japanese air and sea power was already a relatively minor factor and that by the end of 1945 it would be weakened sufficiently to permit a successful invasion. Any sizeable reinforcement to Japan from China or Manchuria could be effectively interdicted by the powerful ships and planes of the U. S. Fleet and by air strikes from Okinawa. In addition, the enemy's shipping potential had declined to a level that did not permit material strengthening of forces in Japan by transport from the Asiatic coast. By December, the combined efforts of B-29's and carrier planes would have devastated large areas in Japan to soften the landing sectors and prohibit the rapid maneuver of major Japanese forces. From abroad perspective, it was argued, immediate invasion was considered to be "the quickest way to assure the end of the war."4

In reply to a query from General Marshall requesting his opinion on the problem, General MacArthur pictured the future strategy in the Western Pacific as presenting three principal courses of action. First, the Allies could encircle Japan by further Allied expansion to the westward, at the same time deploying maximum air power preparatory to attacks on either Kyushu or Honshu in succession, or on Honshu only. A second course would be to isolate Japan completely by seizing bases to the west and endeavoring to bomb her into submission without actually landing in force on the Homeland beaches. The third course open was to attack Kyushu directly and install air forces to cover a decisive assault against the principal island of Honshu.5

General MacArthur went on to analyze the relative merits of each of the choices offered. The first course, he felt, provided greater air power and a high degree of pre-assault neutralization, in addition to achieving the eventual isolation of Japan, but it had the great disad-

[397]

vantage of deploying the bulk of available resources off the main axis of advance. Such a course would fail to increase short-range air coverage of vital portions of the Japanese islands and yet, by spreading Allied strength in the Pacific over a wide area, would prevent an attack on the Japanese mainland until after redeployment from Europe could be accomplished. General MacArthur also expressed the fear that United States forces would become progressively more involved in the China area, perhaps necessitating a further postponement of the Honshu operation.

The second course of action-reliance upon bombing alone-General MacArthur considered to be capable of accomplishment with a minimum loss of life but at the risk of prolonging the war indefinitely. In addition, he stated:

[It] would fail to utilize our resources for amphibious offensive movement; assumes success of air power alone to conquer a people in spite of its demonstrated failure in Europe, where Germany was subject to more intensive bombardment than can be brought to bear against Japan, and where all the available resources in ground troops of the United States, the United Kingdom, and Russia had to be committed in order to force a decision.6

The third course, involving assaults directly against Kyushu and Honshu, had several strong arguments in its favor and was analyzed by General MacArthur as follows:

[It] would attain neutralization by establishing air power at the closest practicable distance from the final objective in the Japanese islands; would permit application of full power of our combined resources, ground, naval, and air, on the decisive objective; would deliver an attack against an area which probably will be more lightly defended this year than next; would continue the offensive methods which have proved so successful in Pacific campaigns; would place maximum pressure of our combined forces upon the enemy, which might well force his surrender earlier than anticipated; and would place us in the best favorable position for delivery of the decisive assault early in 1946. Our attack would have to be launched with a lesser degree of neutralization and with a shorter period of time for preparation.7

Examination of the advantages and disadvantages of the various courses of possible action, General MacArthur concluded, indicated that the last of these outlined strategies was clearly the preferable plan. Unless there was insufficient supporting air power available or the resources in the Pacific could not be gathered in time to initiate the assault by 1945, he advocated the immediate adoption of this last course.8

General MacArthur had little doubt that sufficient power to overcome Japanese resistance could be massed in the Fall of 1945 for an invasion of Kyushu. (Plate No. 113) He stated his reasons as follows:

I am of the opinion that the ground, naval, air, and logistic resources in the Pacific are adequate to carry out Course III. The Japanese Fleet has been reduced to practical impotency. The Japanese Air Force has been reduced to a line of action which involves unco-ordinated, suicidal attacks against our forces, employing all types of planes, including trainers. Its attrition is heavy and its power for sustained action is diminishing rapidly. Those conditions will be accentuated after the establishment of of our air forces in the Ryukyus. With the increase in the tempo of very long range attacks, the enemy's ability to provide replacement planes will diminish and the Japanese potentiality will decline at an increasing rate. It is believed that the development of air bases in the Ryukyus will, in conjunction with carrier-based planes, give us sufficient air power to support landings on Kyushu and that the establishment

[398]

of our air forces there will ensure complete air supremacy over Honshu. Logistic considerations present the most difficult problem.9

From the standpoint of weather, which was a determinative factor in any plan for operations again Japan, General MacArthur thought that the Kyushu assault should be made in November rather than December and suggested that the tentative date for "Olympic," previously adopted by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, be moved forward one month.

Admiral Nimitz, although suggesting several modifications in the general strategy, was in full agreement with General MacArthur's opinion that the invasion of Kyushu should be effected at the earliest date. He concurred in the selection of 1 November as the day on which to launch the invasion.10 In a series of conferences at Manila in mid-May, General MacArthur's and Admiral Nimitz's planning staffs formulated the broad principles to be incorporated into the plan for "Downfall" and submitted their conclusions to Washington.11

On 25 May, the Joint Chiefs of Staff issued the directive for the "Olympic" operation against Kyushu, setting the target date for 1 November 1945. Under this directive, General MacArthur was given the primary responsibility for the conduct of the entire operation including control, in case of exigencies, of the actual amphibious assault through the appropriate naval commander. In addition, he was directed to make plans and preparations for the continuance of the campaign in Japan and to co-operate with Admiral Nimitz in the formulation of its amphibious phases. Admiral Nimitz, in turn, was charged with the responsibility of carrying out the naval and amphibious phases of "Olympic." The land campaign and its requirements were to be given first priority in all subsequent preparations for the Kyushu assault. The Commanding General of the Twentieth Air Force was directed to co-operate in the planning and execution of "Olympic" and also to assist the campaign in Honshu.12

The concept of "Downfall" visualized attainment of Japan's surrender by two successive operations: the first, to advance Allied land-based air forces into southern Kyushu in order to develop air support for the second-a "knockout blow to the enemy's heart in the Tokyo area."13 These operations would be expanded and continued until all organized resistance in the Japanese Home Islands could be brought to an end.

When the plans for "Downfall" were drawn in April 1945, certain suppositions regarding both Allied and enemy capabilities were made. It was assumed that the entire resources of the Pacific would be at the disposal of General MacArthur and Admiral Nimitz for the conduct of the operation; that the flow of redeployed United States Army forces to the Pacific Theater would be maintained after the surrender of Germany; and that required base establishments, staging facilities, and heavy cargo shipping would be available for the mounting and continued support of the forces

[399]

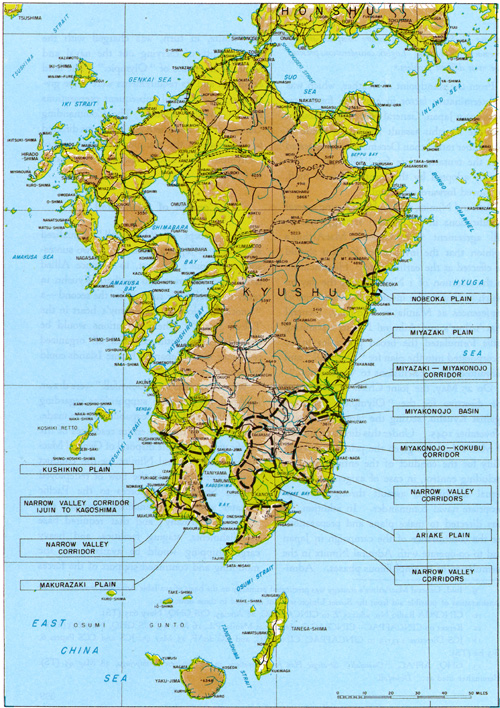

PLATE NO. 113

Kyushu

[400]

committed.

It was also assumed that, at the initiation of the assault, United States forces would be established on the Bonins-Ryukyus line. It was estimated that by then land-based planes would have attained air superiority over southern Kyushu while the U. S. Pacific Fleet, operating from forward naval bases in the Philippines, Ryukyus, and Marianas, would dominate the waters east of Japan and the southern part of the East China Sea.

For the purpose of planning, it was presumed that the Japanese would continue the war to the limit of their capabilities, bending every effort to defend the Homeland with their full strength. Such a defense would include not only opposition by their organized military forces but also a fierce and active resistance by the entire population. The power of the Japanese Navy was discounted as constituting only a minor threat. It was estimated that the bulk of the enemy fleet remnants would be withdrawn to the Yellow Sea or to the western side of the Japan Sea. Submarines and suicide boats would undoubtedly oppose the landings with reckless counterattacks and mines would probably be sown in large numbers. The most effective opposition to the Kyushu assault was expected to come from massed Kamikaze attacks by the remaining strength of the Japanese air forces. It was hoped, however, that continued pounding of enemy airfields and factories would minimize these suicide strikes to the point where Allied losses would not be excessive.14

By early 1945, Japan's overseas military forces were precariously close to disaster. Confronted by decisive defeats on every battlefield and by a rapidly decreasing war potential on the home front, the Japanese Government and Imperial General Headquarters took serious steps to bolster their last remaining defense lines. Plans for the final struggle in the Homeland provided for the utilization of all available resources, both of men and material, within a wide resistance sphere encompassing the key areas in Japan, Manchuria, and China.15

In January 1945, Imperial General Headquarters estimated that the basic strategy of the Allies included the following broad concepts (1) isolation of Japan from the continental and southern resources areas; (2) destruction of her vital industries; (3) elimination of Japan's air, naval, and land forces as threats to an amphibious invasion; and (4) extension of the effective range of U. S. fighter planes to the heart of the Japanese Homeland.16

To carry out these objectives and to prepare for a full-scale invasion it would be necessary, according to the Japanese reasoning, for the United States to strengthen its existing bases and acquire others still closer to Japan. For this reason, Iwo Jima and the Ryukyu Islands were regarded as almost certain targets for future assault.17

At the beginning of 1945, Japan was far from ready to meet a full-fledged Allied invasion. Plans to defend the Home Islands were not considered until after the fall of Saipan in

[401]

July 1944 and even then the outlined preparations were restricted to naval and air force actions with little provision made for ground combat. Even these halfway measures were soon vitiated by the tremendous plane and ship losses incurred in the Philippines Campaign. In the four main islands of Japan Proper only 11 first-line divisions (including 1 armored division) and 3 brigades were available for ground defense until new or reserve units could be mobilized on a large scale. Strategic coastal areas were partially fortified by the construction of heavy artillery positions but no clear-cut Homeland battle strategy had yet been formed.18

By mid January 1945, it had become apparent to the Japanese High Command that a new and comprehensive defense policy was imperative. On 20 January, Imperial General Headquarters issued an outline of policy for future military preparations.

After first stating that the final decisive battle would be waged in Japan Proper, the outline called for an immediate fortification in depth of Japan's defense perimeter. Included in this perimeter were Iwo Jima, Formosa, Okinawa, the Shanghai region, and the south coast of Korea. Resistance in the Philippines was to be maintained as long as possible to delay the advance of the United States forces toward these key positions. While this outer perimeter was being assaulted, the forces in the Homeland would bend every effort to complete preparations for the decisive battle by early Fall of 1945.

On the basis of this general policy directive, Imperial General Headquarters hastened to construct the Homeland defenses. By the end of July 1945, the ground forces in Japan had been increased to a basic strength of 30 line-combat divisions, 24 coastal-combat divisions, and 23 independent mixed brigades, 2 armored divisions, 7 tank brigades, and 3 infantry brigades.19

Defense preparations in Kyushu and in the Tokyo-Yokohama and Nagoya districts of Honshu were particularly emphasized. The various area armies were called upon to protect all points strategically important for tactical defense, for production, and for communications and to complete their preparations to crush any American invasion.20

By April 1945, the course of events made it increasingly probable that Japan would be invaded in late summer or autumn. All key points in the Philippines had fallen; Iwo Jima was lost; American forces had gained a firm foothold on Okinawa; Russia had started to strengthen her forces in Siberia; and Germany

[402]

was on the verge of final defeat. Victory in Europe would provide an additional reservoir of troops and supplies for Allied operations in the Pacific. These climactic developments spurred Imperial General Headquarters to put its paper policies into concrete form and accelerate its preparations for combating a full-scale amphibious invasion.21 On 8 April, a plan for the final campaign on the Japanese main islands was completed and issued. This plan, designated "Ketsu Operation," embodied an extensive program to utilize Japan's remaining potential in the forthcoming last-ditch battle for the Homeland.22

Stressing the necessity for gearing every aspect of national life to the war effort, the " Ketsu Operation " plan provided for the concentration and rapid reinforcement of forces in the critical battle areas of Kyushu and of the Kanto Plain embracing the Tokyo-Yokohama region. Should Kyushu be the initial invasion point, four divisions would be diverted immediately from the Nagoya (Tokai) district, the Kobe-Osaka sector, western Honshu, and Shikoku to reinforce the strength already deployed on the Kyushu battlefronts. Replacements for these divisions would be provided in the centrally located Kobe-Osaka area by the diversion of three or four additional divisions from the Kanto Plain and northern Honshu. On the other hand, should the Tokyo-Yokohama area of the Kanto Plain be invaded first, eight reinforcing divisions would be moved to Nagano and Matsumoto Prefectures north of Nagoya-three from the northern Honshu district, three from the Kobe-Osaka sector, and two from the Kyushu district. If the situation permitted, two divisions from the Nagoya district would also be placed in the Tokyo-Yokohama area. Two divisions advancing from Hokkaido to northern Honshu and five divisions coming from Kyushu and Shikoku to the Kobe-Osaka area would be available for reinforcement.23

Considerable difficulty, however, was anticipated in carrying out this plan. Assuming that the United States would destroy land and water communications, the Japanese made provision for these troop movements to be made on foot, with railroads and ships to be used wherever possible. It was estimated that, if Honshu should be assaulted first, sixty-five days would be required to shift the necessary divisions from Kyushu to the Nagoya district, with ten additional days required to arrive at the battlefield.24

In April 1945, the accelerated preparations for the defense of the Homeland brought about a reorganization of the Japanese army command. The problems raised by the increasing numbers of troops in Japan, the slow-up of defense preparations caused by the lack of manpower and materials, aggravated transportation difficulties, together with the need for co-ordination of operational and administrative functions, made it necessary to simplify the command system.

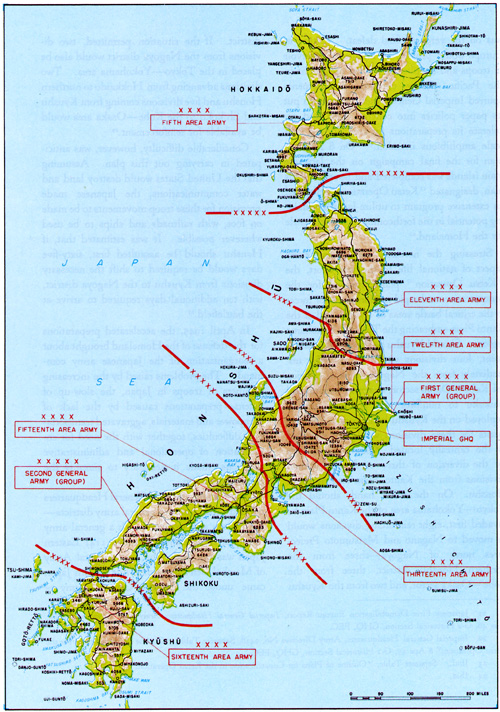

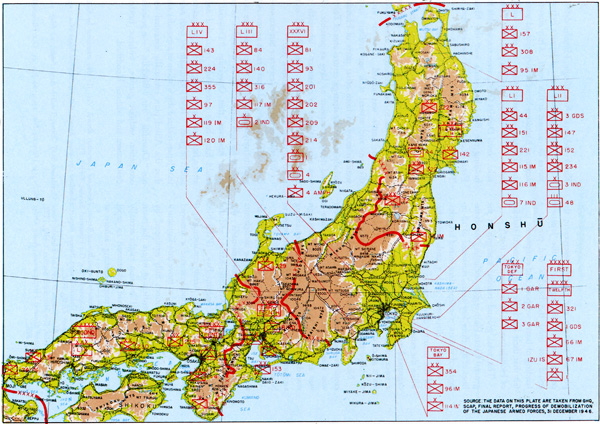

Accordingly, Imperial General Headquarters divided Japan into two general army districts-the eastern and western-with a general army headquarters in each. (Plate No. 114) Eastern Japan was put under the First General Army of Marshal Gen Sugiyama, while western Japan came under the Second General Army of

[403]

PLATE NO. 114

Disposition of Japanese Army Ground Forces in the Homeland, April 1945

[404]

Marshal Shunroku Hata. A new General Air Army Command was established for unified control of army air operations in Japan and Korea with headquarters for the First General Army and for the General Air Army in Tokyo, while Second General Army Headquarters was set up in Hiroshima.25

Under the command of the First General Army were the Eleventh (northern Honshu), Twelfth (Tokyo-Yokohama), and Thirteenth (Tokai) Area Armies. The Second General , Army commanded the Fifteenth (Kobe-Osaka, western Honshu, Shikoku) Area and Sixteenth (Kyushu) Area Armies. The General Air Army controlled the First Air Army (eastern Japan), the 51st, 52nd, and 53rd Air Divisions, and the 30th Fighter Group. The Sixth Air Army (western Japan) remained under the Combined Fleet.26

Almost immediately after the stepped-up home defense program was instituted, American air raids became increasingly severe. Transportation and production facilities were greatly damaged and defense preparations were seriously handicapped. It was almost impossible for the Japanese to put up any effective defense against these air attacks. The loss of the Marianas and the Ogasawara chain, left Japan without bases from which to carry out patrolling activities and, consequently, the Japanese air forces had little or no warning of impending raids. In addition, the small number of planes being produced had to be carefully husbanded for the forthcoming great battle in the Homeland and could not be committed to immediate air defense.

Simultaneously with the growing intensity of these air raids, Japan suffered a long series of reverses between April and June 1945. The loss of the Philippines, Germany's capitulation, the fall of Rangoon, and the American capture of Okinawa-all came as major disasters to Japan. United States activities in the Pacific, meanwhile, gave clear indication that a new offensive would be forthcoming against Japan Proper in the near future.27

Although the Japanese hastened their preparations against the threat of impending invasion, they were faced with a multitude of serious difficulties. Transportation and communications facilities were disrupted, the people were gradually learning of their country's grave plight, and the entire economic situation was deteriorating rapidly. In May 1945, Homeland defense measures, particularly air and naval, were far behind schedule, while the over-all civilian defense program was still in a disorganized state.28

Despite these obstacles, certain air and naval measures had been accomplished. By the summer of 1945, approximately 8,000 suicide or special-attack planes had been produced by converting army and navy fighters, bombers, trainers, and reconnaissance planes. Plans included 2,500 more to be made available by the end of September. Training of pilots was stressed, primarily to develop quickly the ability necessary to fly these craft on suicide missions. Naval preparations also included intensified production of special-attack boats and midget submarines.29

With the final loss of Okinawa in late June

[405]

and the large-scale air raids over their main cities, it became increasingly evident that Japan was in desperate straits-and that the time was fast approaching when the war would be waged in their own islands.

Before any extensive defense measures could be put into effect, the Japanese High Command had to formulate a concrete estimate of Allied intentions. Only by an accurate assessment of the timing and strategy projected in United States plans and by a correct disposition of their own strength, could Japan's military leaders hope to upset or repel an invasion of the mainland.

Opinions within Imperial General Headquarters differed on the question of impending Allied operations. The various views fell into two main categories: one maintaining that the United States would initiate a long-range program of intensified blockade and strategic air bombardment to destroy completely Japan's combat potential, while the other considered that the war would be brought to a decisive stage by an immediate amphibious invasion of Japan Proper. Although these two possibilities were injected into all discussion on strategy, they were not given equal prominence. The majority of Japan's military planners adhered consistently to the latter view-that an Allied invasion in force would be launched as soon as the necessary men and ships could be massed.

In order to carry out definite defense measures, a decision as to which course of action to prepare for became necessary. By 1 July 1945, Imperial General Headquarters adopted the official position that the United States would seek a quick end to the war by an all-out ground force invasion coupled with intensified sea and air operations. It was assumed that new forward bases for air and naval action would be seized in the northern Ryukyus, the Izu Islands, and possibly Quelpart Island. After these preliminary moves, the Japanese expected strong amphibious assaults against the southern part of Japan Proper. Tanega Island, Osumi Peninsula, and other strategic areas in south Kyushu and along the southern coast of Shikoku were named as the most likely targets to be occupied by Allied forces. The possibility of a diversionary feint at Hokkaido to cover the main landings was also taken into account.30

In general, the time of the southern Japan operations was placed in the Fall of 1945 and the date of the decisive Kanto Plain operation, in the Spring of 1946. The date of invasion, the Japanese thought, would depend to a large degree upon the number of troops and the amount of shipping the United States considered necessary for large-scale successful landings. It was calculated that by the Fall of 945, the United States would be able to mount a total of thirty divisions for amphibious operations against the Homeland and that a cumulative total of fifty divisions could be massed by the Spring of 1946.

The general conclusion drawn in the Japanese estimate of Allied capabilities in July 1945 was that the United States was mustering enormous and overwhelming military strength for use against Japan and that the great battle would be joined between early Fall of 1945 and Spring of 1946.31

Geography and Road Net of Kyushu

Kyushu, the southernmost of Japan's four main islands, extends about 200 miles from

[406]

north to south and has a general width of about 80 to 120 miles from east to west. More than three-quarters of its territory consists of mountainous terrain, with a few plainlands scattered along the coasts.

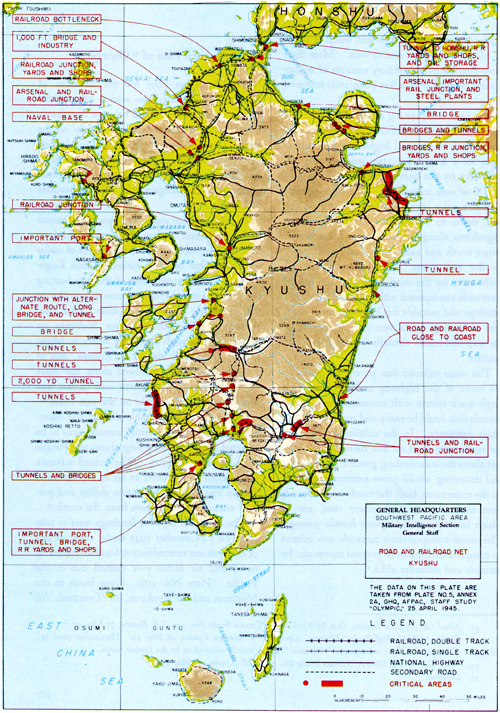

The road net running across the island was limited and in poor condition. (Plate No. 115) The Kokudo or national highway was a euphemism for a single-loop, two-lane gravel road, badly torn by the heavy military traffic in constant flow over its surface. The highway was built along the island's coast, running on the west down to Kushikino, cutting across to Kagoshima, along the north bay to Miyakonojo, thence north and east to Miyazaki and finally up the east coast. The inland prefectural roads were, for the most part, one and a half lanes wide interspersed with frequent "passing" locations and suitable for light transport only. The remaining roads were narrow, primitive, one-way dirt tracks virtually impassable in wet weather.

The main railroad line paralleled generally the route of the highway and consisted of a single-track system with numerous bridges and tunnels that could be easily and quickly blocked when necessary. In the cultivated lowlands, the roads were built on fills rising four to five feet above the surrounding ground. By-passing and detouring would prove extremely difficult. In the mountains, both the roads and railroads were channeled through many cuts, any of which could be sealed against hostile passage. The entire transportation network was subject to complete disruption to prevent movement by attacker and defender alike.32

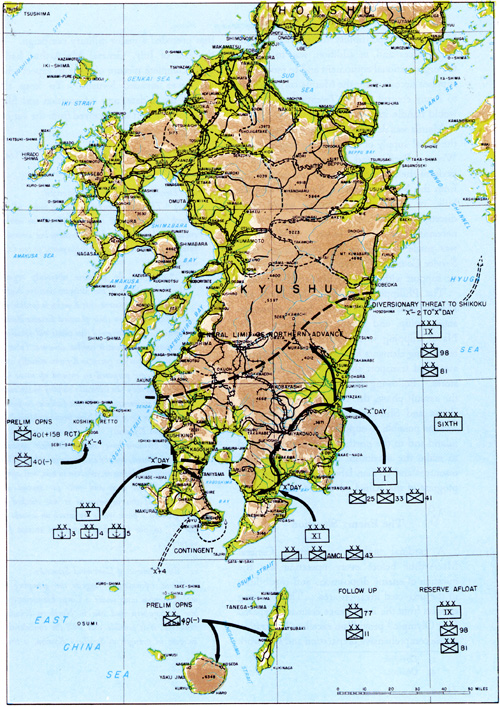

The American plan for the invasion of Kyushu contemplated the seizure of only the southern part of the island below a line drawn from Tsuno on the east coast to Sendai on the west. The 3,000 square miles thus marked off were deemed sufficient to provide the air bases necessary for short-range support of the final operations planned against the industrial centers of Honshu.33

In this southern portion selected for invasion under " Olympic " plan, there were four lowland areas suitable for the development of major airfields. One of these extended from Kagoshima, on the western shore of the bay bearing the same name, through a narrow corridor to the Kushikino plain on the East China Sea. A second ran northward from Shibushi on Ariake Bay, through a twisting valley to Miyakonojo; the third started at Kanoya, east of Kagoshima Bay and followed along the coast of Ariake Bay. The fourth and largest was located north of Miyazaki on the east coast.34

To acquire these valuable areas in the shortest possible time, the initial assaults were to be directed toward securing Kagoshima and Ariake Bays as ports of entry. The inland advance would then be extended as far as the Tsuno-Sendai line to block mountain defiles and prevent enemy reinforcements from the north.35

The southern Kyushu landings were to take place on 1 November 1945 under cover of one of the heaviest neutralization bombardments by naval and air forces ever carried out in the Pacific. (Plate No. 116) From bases in the Marianas and the Ryukyus, the Twentieth Air

[407]

PLATE NO. 115

Road and Railroad Net, Kyushu

[408]

PLATE NO. 116

Organization of Forces for "Olympic"

[409]

Force would attempt to seal the source of Japan's industrial potential by striking ruthlessly at her factories and transportation system. The steady pounding by the huge B-29 bombers, increasing in tempo and fury with each passing day, was expected to reduce materially Japan's ability to maintain her large military organization intact or to distribute effectively her remaining power.36

Simultaneously, carrier task forces would carry out repeated raids against vital coastal areas, attacking enemy naval and air forces, disrupting communications on shore and at sea, and aiding the long-range bombers in attacks against strategic targets. The Far East Air Force, based in the Ryukyus, would concentrate on selected objectives calculated to destroy Japan's air arms both in the Homeland and in nearby North China and Korea. By intercepting shipping and shattering communications, the Far East Air Force would complete the isolation of southern Kyushu and prepare it for amphibious assault.37

It was intended that these air raids be intensified with the approach of the target date to culminate in an all-out effort from X-10 to X Day. These last ten days before the landing phase would see the massed bombing power of all available planes, both land and carrier-based, directed in a mighty assault to reduce the enemy's defenses, destroy his remaining air forces, isolate the objective area, and cover the preliminary mine sweeping and naval bombardment operations. The fortifications within the selected landing areas would be smothered under tons of explosives, while naval vessels and engineer units moved in to eliminate underwater mines and barriers. Supported by such overwhelming and concentrated power, it was expected that the amphibious forces would be able to stage the assault landings without unreasonable losses.

To conduct the preliminary operations of clearing the routes of approach to the landing beaches, seizing emergency anchorages, and initiating the shore bombardment, an Advanced Attack Force would be launched from the Philippines to arrive off Kyushu on X-4. Strong air cover would be furnished this advance force.38

The Main Attack Force would proceed from the four key Pacific bases-Hawaii, the Marianas, the Philippines, and the Ryukyus-and, protected by the U. S. Pacific Fleet and a solid air umbrella, would converge on southern Kyushu by X Day for a three-pronged landing in the Miyazaki area on the east, at Ariake Bay on the south, and at Kushikino, on the west.39 (Plate No. 117)

Two main deception efforts were planned, one strategic and the other tactical. To encourage the belief that Allied attention was focused primarily on the Asiatic coast and the Chusan Archipelago, the China Theater Command and the Southeast Asia Command would conduct diversionary ground movements in China and in the Malay Peninsula. The tactical diversionary effort would be made by a feinting blow against the island of Shikoku. A floating reserve of two divisions, a part of the Main Attack Force, would appear off eastern Shikoku from X-2 to X Day and then, after its deceptive mission was performed, would proceed to the Ryukyus to be available for reinforcement call.

After the beachheads were safely established, reserve and service troops would be brought forward, land-based aviation installed progressively, and logistic facilities developed. Military

[410]

Government would be instituted as soon as practicable after the objective areas were consolidated.40

Employment of "Olympic" Ground Forces

Since the Joint Chiefs of Staff directive of 3 April 1945 was based on the premise that forces from Europe would not be available in time for "Olympic," General MacArthur's plan for the employment of his ground forces involved primarily those combat troops already within the theater. The assault on Kyushu was assigned to the veteran Sixth Army under General Krueger. (Plate No. 118)

The 40th Division, reinforced, was named as the advance attack force and given the mission of seizing positions in the Koshiki Island group located off Kyushu's southwest coast opposite Sendai. The division was expected to establish emergency naval and seaplane bases in these islands and clear the sea routes to the coastal invasion area of Kushikino. The 40th Division was also given the mission of making preliminary landings in the four islands of Tanega, Make, Take, and Io off the southern tip of Kyusyu. These latter islands would be occupied to safeguard the subsequent passage of friendly shipping through the strategic Osumi Strait.41

On X Day, three corps would effect simultaneous assault landings in the three objective areas. V Marine Amphibious Corps (3rd, 4th, and 5th Marine Divisions) would go ashore in the vicinity of Kushikino, drive eastward to secure the western shore of Kagoshima Bay, and then turn north to block the movement of enemy reinforcement from upper Kyushu. XI Corps (1st Cavalry, Americal, and 43rd Divisions) would land at Ariake Bay, capture Kanoya, advance to the eastern shore of Kagoshima Bay, and then move northwestward to Miyakonojo. I Corps (25th, 33rd, and 41st Divisions) would make its assault at Miyazaki on the east coast, move southwestward to occupy Miyakonojo and clear the northern shore of Kagoshima Bay to protect the northeast flank. XI Corps (81st and 98th Divisions), initially in the Sixth Army Reserve afloat, was selected to carry out the diversionary threat off the island of Shikoku while the other three assault forces moved on the actual landing beaches. Should these four corps prove insufficient to accomplish the tasks assigned, a build-up from the elements earmarked for "Coronet" would be instituted at the rate of three divisions per month beginning about X+30. The "Coronet" operation would be adjusted accordingly.

If he deemed it advisable, General MacArthur would have the reserve elements conduct an amphibious assault near Wakiura on the southern coast as soon as adequate naval support could be assured. The primary aim of all operations was to secure areas suitable for the immediate construction of air bases and to clear Kagoshima Bay for use as a port and naval base. As soon as these objectives were accomplished, General Krueger would consolidate the area south of the Tsuno-Sendai line and prepare to stage four divisions and other forces to aid in the execution of "Coronet."42

Under "Olympic" plan, General MacArthur was charged with the responsibility for the logistic support of all army forces engage in the assault operation, including the Marine Corps units under his command. Admiral Nimitz

[411]

PLATE NO. 117

Staging of Forces for "Olympic"

[412]

PLATE NO. 118

"Olympic," the Invasion of Kyushu

[413]

had similar responsibility for maintaining all naval forces and, in addition, was to furnish the organizational equipment and to mount the supplies necessary for the Marine corps passing to Army control. The Twentieth Air Force would handle its own logistics.43

Manila was designated as the base to provide the initial supply of troops being staged in the Western Pacific, and Hawaii was selected to perform the same function for troops sent out from the Middle Pacific. Re-supply and the bulk of construction materials would come directly from the United States, augmented as necessary from Pacific bases. AFWESPAC was made responsible for organizing Army Service Command "Olympic" to provide logistic support within the Kyushu combat zone.

The Philippines, Ryukyus, Marianas, and Hawaii were the four Pacific bases chosen to stage, equip, and mount the invasion forces. Naval shipping would carry the assault and reinforcing elements forward from the mounting areas and transport the heavy equipment and stores. Following the successful completion of the assault phase, the Kyushu ports of Kagoshima and Shibushi would be developed as soon as possible to support further penetration inland and to the north. It was also planned to make the maximum use of available local resources and civilian labor to help speed the progress of the Allied advance.44

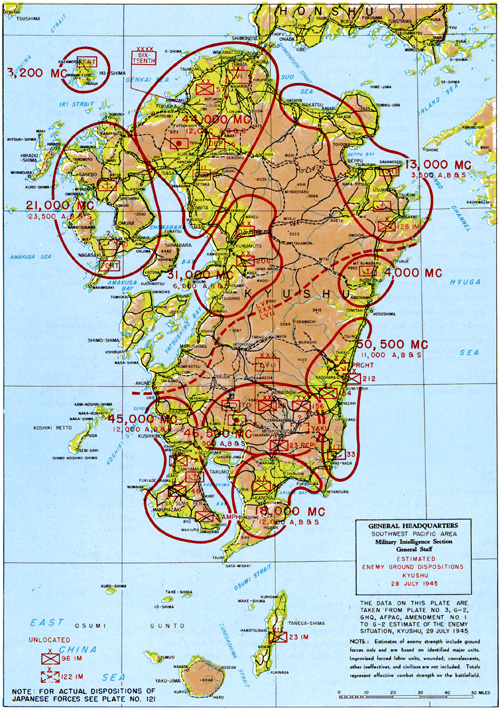

A cardinal problem confronting General MacArthur before every operation was the question of enemy dispositions and capabilities in the projected invasion area. The following extracts from the intelligence estimate prepared for "Olympic" provide an excellent illustration of the comprehensive preparation and staff work that preceded a major military campaign. By the end of July, General MacArthur had a fairly complete picture of what to expect when his forces invaded Kyushu. To keep this picture up to date, new information was filled in as rapidly as it was received from the various intelligence sources.

1. ESTIMATE OF THE ENEMY SITUATION

a. Development of Ground Strength:

(1) The initial estimates on Kyushu of 24 March and 25 April 1945 considered an initial enemy deployment of six (6) divisions but seriously forecast a potentially larger deployment to ten (10) divisions, viz:

"Although the Japanese obviously regard the Tokyo Plain as the ultimate decisive battle ground, it is apparent that Kyushu is considered a critical sector on their planned Empire Battle Position. It is believed that plans will visualize assignment of about 6 combat divisions (plus 2 depot divisions) to garrison Kyushu initially and that they are prepared to expend up to 10 divisions, all they can tactically employ in the area to insure its retention. Depot facilities to maintain such a force would have been established in Northern Kyushu.

These divisions have since made their appearance, as predicted, and the end is not in sight. This threatening development, inherent in war, will affect our own troops basis and calls for special air missions. If this deployment is not checked it may grow to a point where we attack on a ratio of one (1) to one (I) which is not the receipt for victory....

b. ....

c. Development of Command Structure:

Recent information suggests the grouping of mobile combat units under 2 Corps Headquarters, one in Southern and one in Northern Kyushu. However, it is possible that with the considerable increase in strength in Southern Kyushu, a third

[414]

Corps may eventually be formed.45

57 Corps: Established Headquarters at Takarabe (Miyakonojo Basin) during period April-June 1945. Believed responsible for defense of Southern Kyushu, i.e., of area south of central mountain mass.

56 Corps: Headquarters established at Iizuka (east of Fukuoka) during June 1945. Probably responsible for defense of area north of central mountain mass.

d. Organization of Volunteer Defense Units:

Information received since publication of the G-2 Estimate of 24 April 1945, indicates that the Japanese have materially accelerated their mobilization program and are now tapping a hitherto unused source of reinforcement, i.e., they are augmenting Army and Navy Units with large numbers of Volunteer Home Defense Units composed largely of partially trained reservists, over and above increments inducted into the actual armed forces. It has been estimated that approximately 125,000 of these are available in Southern Kyushu and approximately 450,000 in Northern Kyushu . Note the recent assignment of Major Generals as Commanders of 26 of the 51 Regimental Recruiting Districts in Japan, all of which were formerly commanded by Colonels, and of Lieutenant Generals of 10 other similar but generally more populous districts, suggests the grouping of these units of odd size and composition into divisions and possibly even into Corps. It is equally significant that these new Commanders have had recent frontline field commands. Credence is lent this theory by the recent sudden appearance in various parts of Japan of new divisions numbered in the 200 and 300 series whereas the highest previously identified divisional number was 161. Two of these new and unusually high numbered divisions, the 206th and 212th have appeared in Kyushu .... (Plate No. 119)

e. Tactical Significance of Defiles:

(1) The rapidity with which the Japanese are

[415]

PLATE NO. 119

Estimated Enemy Ground Dispositions on Kyushu, 28 July 1945

[416]

effecting their concentration in Southern Kyushu is undoubtedly influenced by the continued availability at full capacity of the two overland roads and railroad routes from Northern to Southern Kyushu. Although some of the incoming units may have arrived by sea and one (the 212th Division) was probably recruited locally, it is probable that 3 to 4 Divisions which are believed to have been activated by Depots in Northern Kyushu and Southwest Honshu utilized one or both of the overland routes. Also, in view of the fact that these troops must be maintained principally by the Kurume and Kumamoto Depots, the roads and rail lines have undoubtedly become vital supply lines. Concern of the Japanese as to the continuity of these overland lines of communications and recognition of their vulnerability to air bombardment is emphasized by recent initiation of Special AA Defense measures....

(2) Attention is invited to the following paragraphs of the G-2 Estimates of 25 April 1945 Par. 1e (4)

" These factors (detailed discussion of critical defiles traversed by east and west coast road and railroad routes from Northern to Southern Kyushu and the part-way alternate route Yatsushiro-Kokubu)-lead to the conclusion that the blocking of a limited number of defiles, i.e., destruction of critical bridges, tunnels, cuts, and fills, by concentrated aerial bombing and vigorous maintenance of interdiction by both air and naval bombardment will render it exceedingly difficult for the Japanese either to reinforce Southern Kyushu with elements of the Northern Kyushu Garrison, or to supply and maintain their forces which are in Southern Kyushu prior to the blocking of their only two lines of overland communication."

Par. 2 a (2) (c)

"Effective interdiction of both coastal routes and the alternate route from Yatsushiro through concentrated aerial bombing and/or naval gunfire would reduce overland reinforcement from Northern Kyushu to a mere trickle as long as maintained. Laborious passage of blocked defiles and long overland marches would be required.... It is probable that the Japanese may resort to night barge movement. An ample supply of small coastal craft is available and their tactics have long stressed the use of this means of troops transport.... Effective air and sea control should limit if not prevent the use of this method...."

Par. 2 a (2) (d)

"Reinforcement from Honshu: Troops from this source would probably be moved into Northern Kyushu via the Shimonoseki Tunnel or by night overwater movement; however, their subsequent movement to Southern Kyushu would be subject to the same restrictions that apply to Northern Kyushu garrison. Overwater movement across the Bungo Channel direct to Nobeoka or points south thereof should be easily prevented by air and/or naval action."

2. CONCLUSIONS

a. The rate and probable continuity of Japanese reinforcements into the Kyushu area are changing the tactical and strategical situation sharply.

At least six (6) additional major units have been picked up in June/July; it is obvious that they are coming in from adjacent areas over lines of communication, that have apparently not been seriously affected by air strikes.

There is a strong likelihood that additional major units will enter the area before target date; we are engaged in a race against time by which the ratio of attack-effort vis-a-vis defense capacity is perilously balanced.

b. The Japanese have correctly estimated Southern Kyushu as a probable invasion objective, and have hastened their preparations to defend it.

c. They have fully recognized the precarious nature of the land and sea routes by which they must concentrate and support their forces in Southern Kyushu. They are vigorously exploiting available time to complete the deployment and supply lines of strong forces in the area before they are deprived of the full use of their limited lines of communication.

d. Since April 1945, enemy strength in Southern Kyushu has grown from approximately 80,000 troops including in mobile combat the equivalent of about 2 Infantry Divisions to an estimated 206,000 including 7 divisions and 2 to 3 brigades, plus Naval, Air-Ground, and Base and Service Troops. This rapid expansion within a few weeks' time, supply of this

[417]

large concentration of troops, and the movement of defensive material has undoubtedly so strained the capacity of all existing lines of communication that any major interruption thereof would seriously reduce the effectiveness of the enemy's preparations. It is also probable that some of the new units identified in Southern Kyushu are not yet fully assembled and that at least one division (the 212th) which was probably formed of local volunteers has not yet been completely equipped.

e. The assumption that enemy strengths will remain divided in North and South (Kyushu) compartments is no longer tenable.

f. The number of enemy major units rapidly tend to balance our attack units.

g. The trend of reinforcements from North to South (Kyushu) is unmistakable.

h. Massing in present attack sectors is apparent.

i. Unless the use of these routes is restricted by air and/or naval action as suggested in Pars. 1 e (4) and 2 a (2) (c), and (d), G-2 Estimate of 25 April, enemy forces in Southern Kyushu may be still further augmented until our planned local superiority is overcome, and the Japanese will enjoy complete freedom of action in organizing the area and in completing their preparations for defense.46

Increasing air raids by American bombers against southern Kyushu and Shikoku in June 1945 gave the Japanese another reason to believe that these areas would be the focal point for the initial invasion of the Homeland. Accordingly, Imperial General Headquarters hastened operational preparations in those areas and gave urgent priority to transporting and accumulating supplies to support the newly organized ground forces of southern Japan.47

Shifting the emphasis of defense to Kyushu necessitated a postponement of military preparations in the Tokyo-Yokohama area. The Japanese feared that if the invasion of the Kanto region should be initiated immediately after the Kyushu attack, or if Honshu should be assaulted directly, an adequate defense could not be made since most of the Japanese air and naval power would already have been committed to Kyushu. For this reason, Imperial General Headquarters were reluctant to transfer ground strength from the capital city area until the very last moment. Although air and sea preparations were being pushed in Kyushu, and supplies and munitions were being moved southward, the Japanese. held up the scheduled commitment of troops to that area pending further developments. They assumed correctly, however, that the first aim of the United States would be the annihilation of the Japanese forces on the southern Kyushu front and the occupation of strategic air bases and harbors in Miyazaki and Kagoshima Prefectures.

Following the invasion of Tanega Shima, where a fighter base would be installed, it was considered probable that the American forces would direct their main attack against the Shibushi area on the Ariake Bay front and the Sumiyoshi coast on the Miyazaki Plain. A secondary attack was expected on Fukiagehama on the Satsuma Peninsula.

[418]

Since these three areas were geographically cut off from each other, it was believed that the Americans would seek to divide and contain the Japanese units therein. The Japanese, therefore, estimated that the first attack would be against either the Miyazaki Plain or the Satsuma Peninsula, or both. The main force of the assault would then in all likelihood be directed at Ariake Bay while other elements would attempt to break through the mouth of Kagoshima Bay. Simultaneously with these attacks by ground forces, an airborne landing would possibly be made on the airfields around Kanoya and Miyakonojo. It was also thought probable that the Tosa Plain of southern Shikoku would be invaded to destroy the launching places of Japanese special-attack planes and, at the same time, establish American fighter bases.

It was anticipated that the United States would employ about 15 divisions, with 10 or 12 divisions attacking southern Kyushu. Two divisions, according to Japanese estimates, would be committed to Shikoku and the rest to strategic reserve. The initial landing force, which was expected to be sufficiently strong to defeat a Japanese counterattack, would probably comprise at least 3 divisions in the main sector and about 2 divisions on the other fronts.48

To counter the expected United States invasion of southern Kyushu, plans were made to attack the main body of the landing force on the sea and in the coastal landing areas. The entire air strength in the Kyushu area would be employed against the invasion convoys. Reconnaissance was to be conducted on a day and night basis along a 600-mile radius of the Homeland by 140 naval reconnaissance planes augmented by army air reconnaissance elements. Secret airfields would be utilized by suicidal special-attack units to escape bombing raids. To conserve air strength for employment against the landing forces, carrier task forces supporting the invasion would be attacked by only a few hundred planes and then only when it became unmistakable that a full-scale invasion was in progress. The bulk of the air fleet of 10,500 planes, mostly of the small special-attack type, would be launched against the warships and transports in the crucial invasion area. Japanese plans called for these planes to be completely expended within a ten-day period in a supreme effort to repel the invasion forces. By the end of June 1945, 8,000 of the necessary craft were already available; the other 2,500 were expected to be finished by Fall.49

The Japanese Navy had little power left to oppose an Allied assault. Its remaining forces consisted of a variety of small underseas special-attack craft and a few heavy surface units that had been hidden from Allied attack. The total destroyer strength of nineteen operational ships was to be distributed along the islands of the Inland Sea . As soon as the invasion convoy entered its anchorage, the destroyers would attack in co-ordination with air force planes and surface and underwater special-attack units. About thirty-four submarines of all types were available for patrol duty and harassment of Allied convoy and supply lines.

The surface special-attack forces, in conjunction with air and other naval units, were ear-marked for strong mass assaults on American transports in the invasion area. Midget submarines (Koryu) would strike at the convoy before and after its entrance into the anchorage."Human torpedoes" (Kaiten) would execute

[419]

PLATE NO. 120

Japanese Ground Dispositions on Kyushu, 18 August 1945

[420]

similar attacks and, in addition, strike at the fleet forces supporting the bombardment while small motorboats (Shinyo) would be employed in night attacks.50

Land preparations on Kyushu in June and July were largely inadequate and an Allied assault at that time would have found Japan's defenses generally incomplete. In their planned policy of playing for time, the Japanese were aided by the strong resistance on Okinawa, which they felt would further delay the invasion date. Utilizing this needed interval, the Japanese implemented their operational plans and hastened to complete all defenses and to co-ordinate all activities for the objective of "annihilating the enemy on the beaches through offensive action."51 Every effort was bent toward this goal and it was estimated that all steps to meet the invasion would be completed by November.

Responsibility for the defense of the Kyushu area was assigned to the Sixteenth Area Army with headquarters at Fukuoka. Under its command were the Fortieth, Fifty-sixth, and Fifty-seventh Armies (each the equivalent of an American corps), one independent line-combat division, four independent coastal-combat brigades, and miscellaneous service units. (Plate No. 120)

By mid July 1945, the Fortieth Army was deployed along the Satsuma Peninsula in southwest Kyushu below Sendai. The Fifty-sixth Army occupied northern Kyushu, with most of its strength distributed along the northwestern coast from Moji to Sasebo. The Fifty-seventh Army was responsible for the defense of the southeast and was concentrated in the Miyazaki Plain region. The total strength assigned to the immediate defense of Kyushu amounted to approximately 7 line-combat divisions, independent mixed brigades, and 3 tank brigades.52 Three divisions and 2 tank brigades were kept in mobile reserve in south central Kyushu to be moved at an instant's notice and concentrated at the points of amphibious invasion.

The Japanese tactical plan called for a rigid defense of the beaches which would be reinforced as rapidly as units could be sent from other parts of Kyushu and the western regions of Honshu. The ridges immediately to the rear of the anticipated landing areas were fortified by a network of large caves and tunnels covered by a series of strong artillery and mortar emplacements and manned by large forces of coastal-combat ground troops. These troops would meet the first assault waves and, together with the line-combat divisions, would endeavor to hold all positions until the arrival of the mobile reinforcements at the beach battleground. If the primary target of the Allies could be ascertained before the landings, then the main Japanese forces would rush to that point. If the Allied target should be unclear or if all points should be invaded simultaneously, then the main enemy strength would be committed to Ariake Bay, while delaying actions were fought on other fronts. In all cases, the decisive engagement would be waged in the beach areas with all available forces moving toward the southern Kyushu coasts. The whole object of the Japanese was to repel the invaders before they could put their heavy armor and artillery ashore.

The Japanese realized that their defense plans contained numerous weak points but their situa-

[421]

PLATE NO. 121

Organization of Forces for "Coronet"

[422]

tion was desperate and they felt compelled to use desperate measures.

American Plans for the Invasion of Honshu-Operation "Coronet"

Four months after the first American troops had fought their way ashore on Kyushu, the next and decisive amphibious operation against Japan would be launched. "Coronet," the invasion of the Kanto Plain area of Honshu, was scheduled for 1 March 1945.53

Two armies, the First and the Eighth, were charged with the second mammoth assault against the heartland of Japan. Their immediate mission was to destroy all opposition and occupy the Tokyo-Yokohama area. General MacArthur would exercise personal command of the landing forces and direct the ground operations on the mainland. With him would be the advance echelon of his General Headquarters to act as the Army Group Headquarters in the field.

Operation "Coronet" would be supported by all army and navy forces in the Pacific and, in addition, would be augmented by numerous combat units redeployed from Europe. Air, naval, and logistic support was outlined along the same general pattern as "Olympic" except on an enlarged scale. The command relationships established between General MacArthur, Admiral Nimitz and General Spaatz were to continue. (Plate No. 121)

The initial landings would be staged by 10 reinforced infantry divisions, 3 marine divisions, and 2 armored divisions. Launched from the Philippines and Central Pacific bases, the attacking forces would be constantly protected by ships and planes of the Pacific Fleet as well as by land-based aircraft. Thirty days after the initial assault, each army would be reinforced by a corps of 3 divisions. Five days after this reinforcement, an airborne division and an AFPAC Reserve Corps of 3 divisions would be made available. These 25 divisions were to seize the Kanto Plain, including the general areas of Tokyo and Yokohama, and then carry out any additional operations necessary to break Japanese resistance. Strategic reserve for the entire operation would consist of a corps of 3 divisions located in the Philippines and a sufficient number of divisions from the United States to permit reinforcement at the rate of 4 per month.

The amphibious assault against Honshu would be preceded by heavy blows of Allied naval and air forces against the Japanese Empire. Carrier planes from the Pacific Fleet would co-operate with the Strategic Air Force in carrying out repeated attacks against vital areas of the Japanese Home Islands to strangle land and sea communication and wipe out selected targets ashore. Land-based planes from newly won fields in Kyushu together with fighters and bombers from Okinawa would continue to range over the Empire and the Asiatic coast, destroying any remaining enemy aircraft, shattering land communications, and reducing defensive installations. All air attacks would be intensified as the landing date approached, culminating in an all-out effort, co-ordinated with naval bombardment, during the last fifteen days.

At the same time, subsidiary actions in other theaters of operations would be aimed at containing Japanese air and ground forces. The China Theater would conduct neutralizing air and ground attacks against the enemy on the Asiatic mainland. The Southeast Asia Command would launch similar operations in the

[423]

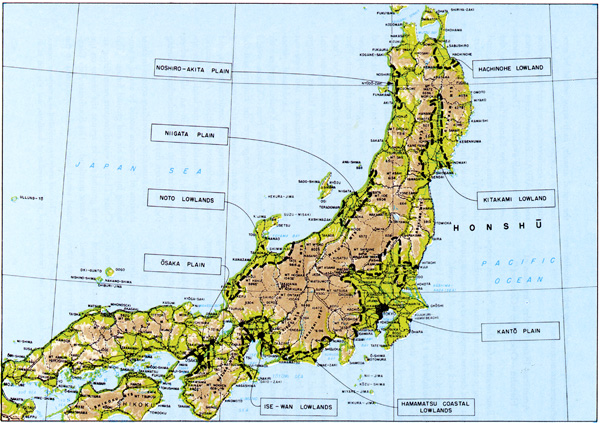

PLATE NO. 122

Honshu

[424]

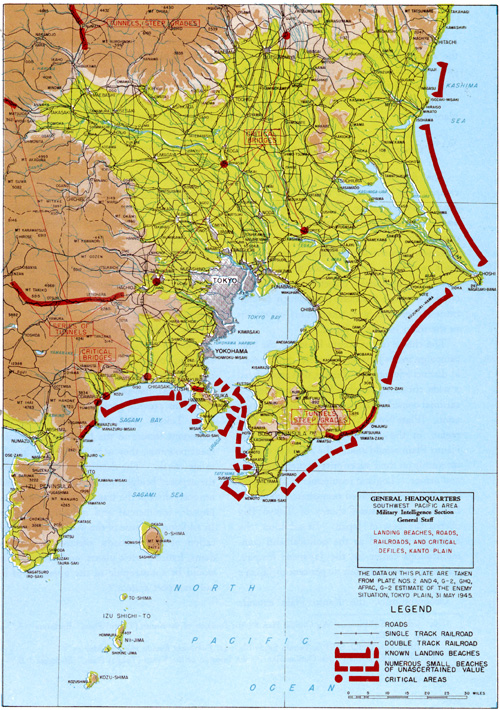

PLATE NO. 123

Landing Beaches, Roads, Railroads, and Critical Defiles, Kanto Plain

[425]

southern areas. Naval and air forces based in the Aleutians would be called upon to lend general support wherever possible. All plans were directed toward the successful execution of the greatest amphibious operation ever planned.

The decisive operation in the projected campaign to bring about the final collapse of Japan was the invasion of Honshu. (Plate No. 122) The total defeat of Japan's armies in the core of the Empire was the over-all primary objective. In the event that the campaign in the Kanto Plain did not prove to be the last battle, the secondary objective would be achieved-secure positions from which to continue air, ground, and amphibious operations in the main islands of Japan.

The choice of the Kanto Plain for the final campaign in the Japanese Homeland had several distinct advantages. Firstly, that area offered a wide choice of suitable landing beaches-a cardinal consideration in any amphibious operation. (Plate No. 123) As the largest lowland region in the Japanese Home Islands, the Kanto Plain would enable the Allies to capitalize readily on their superiority in mechanization and armor. Logistic requirements to support the large forces involved necessitated good port facilities; the western shores of Tokyo Bay offered the best in Japan. In addition, the Kanto area served as the political and communications center for the Japanese Empire, containing approximately 50 per cent of Japan's war industry.54

Geographically, the Kanto Plain extends approximately 80 miles north and south and 70 miles east and west, covering between 5,000 and 6,000 square miles. The north and west sides are bordered by the mountainous masses of central and northern Honshu, which rise sharply to heights of 1,000-8,000 feet. Its eastern side is bounded by the Pacific Ocean and its southern side, by the waters of Tokyo and Sagami Bays.55 The outer reaches of the Plain have three principal landing areas, each fronted with long sandy beaches, generally well suited to amphibious operations. These are the Kashima and Kujukuri beaches on the east coast, and Sagami beach at the head of Sagami Bay. From each of these landing points, fairly good routes lead into the Kanto Plain. Landings made in other regions would require overland movements through narrow, easily defended corridors.56

The capital of Tokyo is the hub of a widespread network of roads and railroads radiating outward along the Kanto Plain to northern, western, and southwestern Honshu. Numerous transverse roads and railroads within the Plain provide good routes of travel to or from Tokyo. Although these routes were important factors to the Japanese in reinforcement potential, they were relatively vulnerable to air attack. The destruction or blockade of the exposed bridges, tunnels, and defiles would seriously disrupt the transportation system and impede commercial and industrial activities. In addition, because of the widespread electrification of the railroads, effective bombing of dams, hydro-electric plants, and power stations would be catastrophic to the operation of the rail transport system.57

[426]

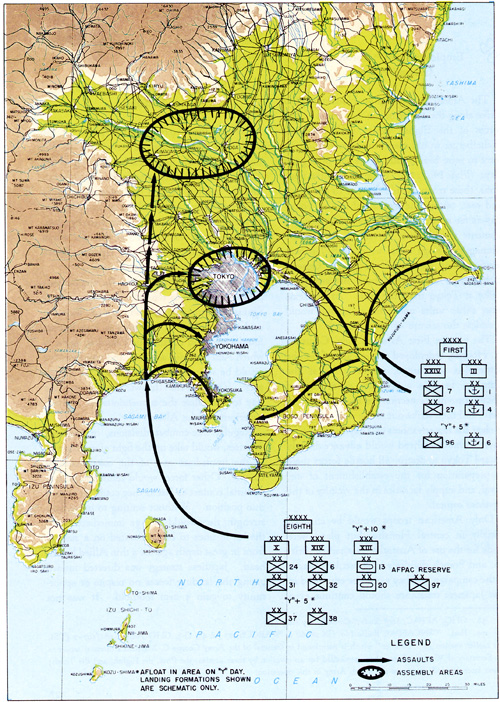

Employment of "Coronet" Ground Forces

The American landings on Honshu were to strike along the center of the east coast. The forces of the Eighth Army under General Eichelberger would constitute a western attack force to seize beachheads at the top of Sagami Bay. (Plate No. 124) From their initial positions, these troops would fan out to the north and east, taking the western shores of Tokyo Bay as far north as Yokohama. The armored elements would drive beyond Tokyo to the Kumagaya-Koga area to cut off Japanese reinforcement routes. If necessary, General Eichelberger would turn back his armor to strike at Tokyo from the rear. At the same time, other units under his command would complete the seizure of Yokohama.58

The veteran First Army of Gen. Courtney H. Hodges, redeployed to the Pacific from the battlefields of Europe, would strike at the Kujukuri beaches about fifty miles east of Tokyo, provide protection for the northeastern flank, and then strike out to the west and south to clear the eastern shores of Tokyo and Sagami Bays. One spearhead would advance directly toward Tokyo to destroy all hostile forces there in preparation for the establishment of air, naval, and supply facilities in the vicinity of the Japanese capital.

Only American troops would be engaged initially in central Honshu, but plans were made for the use of Australian, Canadian, British, and French divisions in subsequent stages of the campaign. They would be employed in case Japanese resistance should continue even after the heart of their Homeland was in American hands.59

Enemy Plans for the Defense of Honshu

By mid June 1945, Japanese plans for the vital campaign in Honshu envisioned an all-out battle on the main beaches leading to the Kanto Plain. Kashima-nada, Kujukuri-hama, and the head of Sagami Bay were regarded as the crucial areas to be held at all costs against an amphibious invasion. Of the three beaches, Kujukuri-hama was selected as the area where the prime initial effort of the Japanese forces would be concentrated.

The general strategy called for the coastal-combat divisions to send their entire resources against the American assault head-on, with the underlying objective of merging all lines into an interlocking and continuously fluid struggle in which American air, artillery, and naval gunfire would be seriously hampered in choice of targets. It was felt that this was the only possible way to neutralize the tremendous air and sea superiority of the Allies.

Regular line-combat divisions, in prepared defenses, would take up the fight alongside and in the immediate rear of the coastal-combat troops. Other forces would reinforce the area of initial contact as fast as they could be moved into position. Without waiting to mass their strength, they would plunge immediately into the battle lines to be committed on a narrow front in great depth against a thin Allied beachhead. Japanese strategy was directed toward giving the landing forces no respite or opportunity to gain a firm foothold. It was not

[427]

PLATE NO. 124

"Coronet," the Invasion of Honshu

[428]

PLATE NO. 125

Japanese Ground Dispositions on Honshu, 18 August 1945

[429]

planned to keep any sizeable reserves in the central Kanto Plain region. If the Japanese could not hold the beaches and prevent a landing of heavy weapons and equipment, they felt that their last hope of a successful defense of Honshu would be irretrievably lost.60

The total ground combat strength in the general Kanto Plain region, including the shorelines of the three key areas, consisted of 18 in fantry divisions, 7 independent mixed brigades, 2 armored divisions, and 3 tank brigades. Of the infantry divisions, 11 were line-combat while the other 7 were made up of the specially organized coastal-combat troops. In addition, a force of division strength was organized to make a last-ditch stand in the heart of the city of Tokyo and around the Imperial Palace.61

No definite provisions were made for the employment of air power in the event Honshu was assaulted in the spring of 1946, since it was anticipated that the Kyushu campaign would have consumed Japan's entire remaining air force. Special-attack surface craft were to be utilized to the fullest extent.

By July 1945, the Japanese had deployed an army at each of the three probable battlefronts-the Fifty-first Army at Kashima-nada; the Fifty-second Army at Kujukuri-hama; and the Fifty-third Army at Sagami Bay. (Plate No. 125) The Thirty-sixth Army, consisting of 6 line-combat infantry divisions and 2 armored divisions, was scheduled to move into Kujukuri-hama and be in position, fully equipped, by January 1946. Regardless of where the main force of the anticipated invasion might actually strike, the Japanese had determined to repel first any American troops coming ashore at Kujukuri-hama. Accordingly, Honshu defense plans directed that the bulk of Japan's fighting forces be massed at this point. Only after the action at Kujukuri-hama was completed would the Japanese offensive move to other battle fronts. The Tokyo Bay Group and the Yokosuka Naval District Group were responsible for holding the Boso Peninsula and the Miura Peninsula to prevent Allied penetration of Tokyo Bay.62

The Tokyo Defense Army had been formed late in June 1945 to bolster the weak defenses of the capital. This force, consisting of three infantry brigades and two independent engineer battalions, was to be reinforced immediately after the battle was joined. Two or three divisions and several tank and artillery units were to move in from other parts of Honshu to help secure the strategic central area of Tokyo and delay its capture as long as possible. It was also planned to construct a labyrinth of underground fortifications manned and supplied to resist for more than a year.63

Whether or not these desperate but extensive defense measures would have made an invasion prohibitively expensive in American lives is a matter for speculation. It is reasonable to assume, however, that Operation "Downfall" could have been successfully concluded only after a hard and bitter struggle with no quarter asked or given. It was fortunate for both sides that Japan realized the wisdom of surrender and that the Allied plan eventually executed was not "Downfall" but "Blacklist"-a peaceful occupation without gunfire, without further destruction, and without bloodshed.

[430]

Go to: |

|

|

Last updated 20 June 2006

|