CHAPTER XXI

RETURN TO PEACE

Imperial Announcement of Surrender

With the promulgation late on 14 August of the Emperor's Rescript accepting the Allied surrender terms, Japan's decision to capitulate had become final. But not until thirteen hours later did the nation at large learn the tragic and stunning news that the Empire had bowed in defeat for the first time in its recorded history.1

From early morning on 15 August, radio stations throughout the country alerted the people to stand by for an important broadcast at 12 o'clock noon. In Tokyo and other cities, special preparations were hastily carried out to ensure that a maximum number of people would hear the broadcast. Loudspeakers were set up in public places as well as in government and private offices where most employees stayed during the noon hour to eat meager box lunches.

As the time for the broadcast drew near, tense expectancy gripped the nation. In homes, offices and factories and on city streets through-out the land, people paused to gather near radios or loudspeakers. Few outside of limited official and press circles had any inkling of what was to come. The vast majority of the nation, even though feeling that defeat could not be far off, expected that they were about to hear a new exhortation to fight to the death or the announcement of an Imperial declaration of war on Soviet Russia.

The strident note of the noon time-signal was followed by the muted strains of the national anthem. Then, listeners heard State Minister Shimomura, President of the Cabinet Information Board, announce that the next voice would be that of His Majesty the Emperor. People caught their breaths in quick surprise for never before had the Emperor spoken directly to his subjects by radio. They listened in tense silence as the Emperor's voice came over the air, reading the solemn and fateful words of the Imperial Rescript:2

After pondering deeply the general trend of the world situation and the actual state of Our Empire, We have decided to effect a settlement of the present crisis by resort to an extraordinary measure. To Our good and loyal subjects, we hereby convey Our will.

We have commanded Our Government to communicate to the Governments of the United States, Great Britain, China and the Soviet Union that Our Empire accepts the terms of their joint Declaration.

To strive for the common prosperity and happiness of all nations as well as the security and well-being of Our subjects is the solemn obligation handed down to Us by Our Imperial Ancestors, and We keep it close to heart. Indeed, We declared war on America and Britain out of Our sincere desire to ensure Japan's

[727]

self-preservation and the stabilization of East Asia. It was not Our intention either to infringe upon the sovereignty of other nations or to seek territorial aggrandizement.

The hostilities have now continued for nearly four years. Despite the gallant fighting of the Officers and Men of Our Army and Navy, the diligence and assiduity of Our servants of State, and the devoted service of Our hundred million subjects-despite the best efforts of all-the war has not necessarily developed in Our favor, and the general world situation also is not to Japan's advantage.3 Furthermore, the enemy has begun to employ a new and cruel bomb which kills and maims the innocent and the power of which to wreak destruction is truly incalculable.

Should We continue to fight, the ultimate result would be not only the obliteration of the race but the extinction of human civilization. Then, how should We be able to save the millions of Our subjects and make atonement to the hallowed spirits of Our Imperial Ancestors ? That is why We have commanded the Imperial Government to comply with the terms of the Joint Declaration of the Powers.

To those nations which, as Our allies, have steadfastly cooperated with the Empire for the emancipation of East Asia, We cannot but express Our deep regret. Also, the thought of Our subjects who have fallen on the field of battle or met untimely death while performing their appointed tasks, and the thought of their bereaved families, rends Our heart, and We feel profound solicitude for the wounded and for all war-sufferers who have lost their homes and livelihood.

The suffering and hardship which Our nation yet must undergo will certainly be great. We are keenly aware of the innermost feelings of all ye, Our subjects. However, it is according to the dictates of time and fate that We have resolved, by enduring the unendurable and bearing the unbearable, to pave the way for a grand peace for all generations to come.

Since it has been possible to preserve the structure of the Imperial State, We shall always be with ye, Our good and loyal subjects, placing Our trust in your sincerity and integrity. Beware most strictly of any outburst of emotion which may engender needless complications, and refrain from fraternal contension and strife which may create confusion, lead ye astray and cause ye to lose the confidence of the world. Let the nation continue as one family from generation to generation with unwavering faith in the imperishability of Our divine land and ever mindful of its heavy burden of responsibility and the long road ahead. Turn your full strength to the task of building a new future. Cultivate the ways of rectitude, foster nobility of spirit, and work with resolution so that ye may enhance the innate glory of the Imperial State and keep pace with the progress of the world. We charge ye, Our loyal subjects, to carry out faithfully Our will.

The Government had taken special pains to phrase the Imperial message in such a way as to soften the impact of surrender on the nation at large. The word "surrender" itself had been studiously avoided. Nevertheless, the import of the Emperor's words was painfully clear to all who heard them. Even those who did not know what the Joint Declaration of the Allied Powers signified-and there were many such in the rural areas-swiftly understood that the Emperor was announcing the termination of hostilities on terms laid down by the enemy. Japan, in short, was accepting final defeat after more than three and a half years of costly fighting and hard sacrifice.4

Although the horrible destruction of Hiro-

[728]

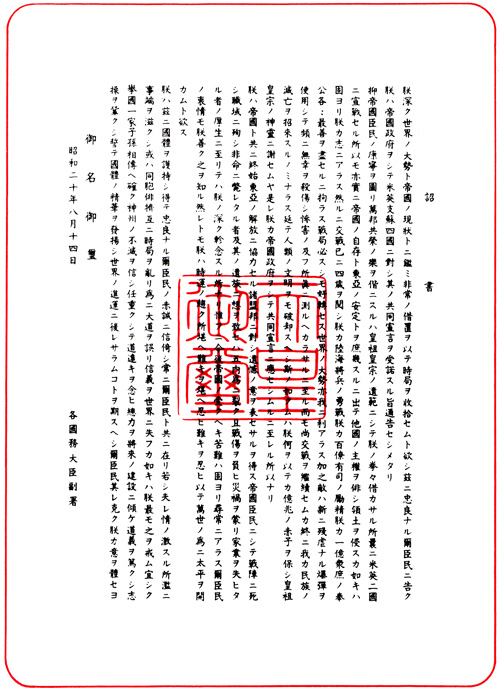

IMPERIAL RESCRIPT To Our good and loyal subjects: After pondering deeply the general trends of the world and the actual conditions obtaining in Our Empire today, We have decided to effect a settlement of the present situation by resorting to an extraordinary measure. We have ordered Our Government to communicate to the Governments of the United States, Great Britain, China and the Soviet Union that Our Empire accepts the provisions of their Joint Declaration. To strive for the common prosperity and happiness of all nations as well as the security and well-being of Our subjects is the solemn obligation which has been handed down by Our Imperial Ancestors, which We lay close to heart. Indeed, We declared war on American and Britain out of Our sincere desire to ensure Japan's self-preservation and the stabilization of East Asia, it being far from Our though either to infringe upon the sovereignty of other nations or to embark upon territorial aggrandizement. But now the war has lasted for nearly four years. Despite the best that has been done by every one-gallant fighting of military and naval force, the diligence and assiduity of Our servants of the State and the devoted service of Our one hundred million people, the war situation has not necessarily improved and the general trends of the world are also not to Japan's advantage. Moreover, the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is indeed incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives. Should We continue to fight, it would not only result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization. Such being the case, how are We to save the millions of Our subjects; or to atone Ourselves before the hallowed spirits of Our Imperial Ancestors? This is the reason why We have ordered the acceptance of the provisions of the Joint Declaration of the Powers. We cannot but express the deepest sense of regret to our Allied nations who have consistently cooperated with the Empire towards the emancipation of East Asia. The thought of those officers and men as well as others who have fallen in the fields of battle, those who died at their posts of duty, or those who met with untimely death and all their bereaved families, pains Our heart night and day. The welfare of the wounded and war-sufferers and of those who have lost their home and livelihood are the objects of Our profound solicitude. The hardships and sufferings to which Our nation is to be subjected hereafter will be certainly great. We are keenly aware of the inmost feelings of all ye, Our subjects. However, it is according to the dictate of time and fate that We have resolved to pave the war for a grand peace for all the generations to come by enduring the unendurable and suffering what is unsufferable. Having been able to safeguard and maintain the structure of the Imperial State, We are always with ye, Our good and loyal subjects, relying upon your sincerity and integrity. Beware most strictly of any outburst of emotion which may create confusion, lead ye astray and cause ye to lose the confidence of the world. Let the entire nation continue as one family from generation to generation, ever firm in its faith of the imperishableness of its divine land, and mindful of its heavy burden of responsibilities, and the long road before it. Unite your total strength to be devoted to the construction for the future. Cultivate the ways of rectitude; foster nobility of spirit; and work with resolution so as ye may enhance the innate glory of the Imperial State and keep pace with the progress of the world. The 14th day of the 8th month of the 20th year of Showa

|

PLATE NO. 167

Imperial Rescript Ending the War

[729]

shima and Nagasaki by the atom bomb, coupled with Soviet entry into the war, had increased popular realization that the war was lost, the sudden, grim news of capitulation caught the nation psychologically unprepared. So thorough had been the indoctrination for a last-ditch defense of the homeland that many at first could not comprehend that Japan had surrendered. Then, as the meaning of the Emperor's words sank in, the people were stunned and bewildered.

Mingled with the sense of shock were grief, despair and disillusionment. To a proud and intensely patriotic people who had never before been conquered in war, defeat was a bitter pill to swallow. Many wept openly as they listened to the Emperor's solemn announcement. Some felt swift anger against the nation's leaders and the fighting services for their failure to avert defeat; others blamed themselves for falling short in their war effort. Above all, there was a feeling of intense sympathy for the Emperor, who had been forced to take so tragic and painful a decision.

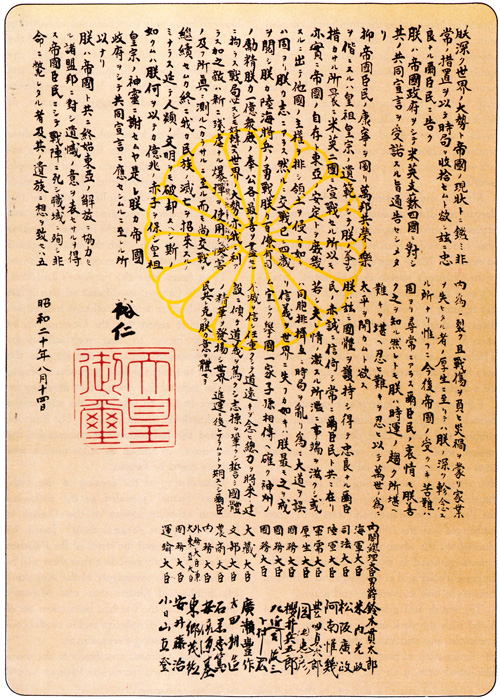

Following the Emperor's broadcast, war factories throughout the country dismissed their workers and closed their doors. The newspapers, which had been ordered to suspend their customary morning editions, came out in the afternoon, all carrying the text of the Imperial Rescript, an unabridged translation of the Potsdam Declaration, and texts of the notes exchanged with the Allied Powers. In Tokyo, throughout the afternoon, crowds of weeping citizens gathered in the vast plaza before the Imperial Palace and at the Meiji and Yasukuni Shrines to bow in reverence and prayer.

The shock and grief of the moment, combined with the dark uncertainty of the future, prevented any widespread feeling of relief at the termination of hostilities. Bombings and bloodshed were at an end, but defeat seemed likely to bring only a continuation of hardship and privation. Starvation already gripped the land. To this might now be added the breakdown of public discipline and order, acts of violence and oppression by the enemy forces of occupation, and a staggering burden of reparations.

Despite the dark outlook, the nation drew solace and courage from the Emperor's assurance that he would remain to lead the people through the difficult period that lay ahead. His appeal for strict compliance with the Imperial will made a profound impression, and "Reverent Obedience to the Rescript" became the rallying cry with which the nation prepared to face the harsh consequences of capitulation.

Three hours after the Emperor's broadcast, the Suzuki Cabinet, its difficult mission at last accomplished, tendered its collective resignation. The Premier stated that the Government, by resigning, meant to bear responsibility for its unprecedented action in appealing to the Emperor to make the final surrender decision, and he declared that it was vitally necessary for younger leaders to take over the stupendous task of national reconstruction.5 The Emperor accepted the resignation but commanded the Government to remain in office until a new Cabinet could be formed.

Broadcasting on the evening of the 15th, Premier Suzuki appealed to the nation to unite in absolute loyalty to the Throne in face of the grave national crisis. Japan, he stated, had accepted the terms of the Potsdam Declaration "fully confident that there will be no change in the sovereignty of the Emperor." He emphasized further that His Majesty's decision to end the war had been taken out of compassion for his subjects and in careful consideration of existing circumstances.

Addressing himself specifically to the members of the armed forces, the Premier voiced

[730]

full sympathy with their feelings regarding surrender. He stressed, however, that it was the primary duty of the Emperor's subjects to assist in fostering the glory and prosperity of the Throne and that this could be accomplished only through complete loyalty and obedience to the Imperial will. He concluded with this exhortation:6

I hope that the intrinsic sincerity of our people will be given full expression in the fulfillment of the terms of the Potsdam Declaration, and that thereby we shall speedily regain the confidence of the world. Our primary concern must be to restore the Empire to its proper place in the world as quickly as possible through conscientious conduct and the display of the moral strength of our nation under Imperial rule. To this end we and succeeding generations must labor mightily and indomitably, uniting as one family in faithful observance of the Imperial Rescript.

The Emperor's personal radio message of the carefully phrased Rescript concerning the surrender decision was couched in almost the exact words used by him in the last Imperial conference. As the members of the Government had hoped, the message had the desired effect. The people at large, though shocked and grief- stricken, were impressed that this decision represented the actual will of the Emperor himself rather than an act of the Government, which the sovereign had merely ratified. As the momentous day of 15 August came to a close, there was scarcely any doubt but that the nation as a whole would obediently accept the Imperial command.

The reaction of the armed forces, however, was more dangerously problematical. Although the top leaders of both fighting services had finally bowed to the Emperor's will at the Imperial conference of 14 August, they themselves were deeply concerned over the possibility of action by the extremist elements within the Army and Navy to defy the surrender decision. In fact, even before this decision was finally taken on the 14th, War Minister Anami was already aware that a coterie of young officers in the War Ministry and the Army General Staff was planning an armed coup d'etat for the purpose of forestalling surrender and establishing a military government which would continue the war.7

This was obviously a situation fraught with danger. The Army leaders had held out until the very last moment against acceptance of the Potsdam terms, and they still might have blocked or seriously impeded the surrender by giving their sanctions to the coup d'etat plan. Nevertheless, when the final decision was taken at the Emperor's command, they loyally decided to obey and took swift action to ensure discipline

[731]

PLATE NO. 168

Scene in Front of Imperial Palace

[732]

and order throughout the Army.

Following the final Imperial conference on 14 August, the Army "Big Three"-War Minister Anami, Chief of the Army General Staff Umezu, and Inspectorate-General of Military Training General Kenji Doihara-chanced to meet at the War Ministry together with Field Marshals Hata and Sugiyama, the top operational commanders of the Army forces in the homeland. These five men affixed their seals to a joint resolution pledging that the Army would "conduct itself in accordance with the Imperial decision to the last." The resolution was endorsed immediately afterward by General Masakazu Kawabe, over-all commander of the Army air forces in the homeland.8

In accordance with this decision, General Anami and General Umezu both called meetings of their ranking subordinates during the afternoon of the 14th, notified them of the outcome of the final Imperial conference, and directed strict obedience to the Emperor's command.9 A short while later, special instructions to the same effect were radioed to all top operational commanders (of General Army level) jointly in the names of the War Minister and Chief of Army General Staff. These instructions stated in part:10

1. Negotiations have taken place with the enemy on the basis of our conditions that the national polity be preserved and the Imperial domain maintained. The stipulations laid down by the enemy, however, rendered the realization of these conditions extremely difficult, and for that reason we vigorously and consistently maintained that these stipulations were absolutely unacceptable. Although we reported to the Throne to this effect on various occasions, His Imperial Majesty nevertheless has decided to accept the terms of the Potsdam Declaration......

2. The Imperial decision has been handed down. Therefore, in accordance with the Imperial will, it is imperative that all forces act to the end in such a way that no dishonor shall be brought to their glorious traditions and splendid record of meritorious service, and that future generations of our race shall be deeply impressed. It is earnestly desired that every soldier, without exception, refrain absolutely from rash behavior and demonstrate at home and abroad the everlasting fame and glory of the Imperial Army.

Simultaneously with the action of the Army leaders, the Navy also took steps to ensure disciplined compliance with the surrender decision. At 1630 on 14 August, Navy Minister Yonai communicated this decision to his principal subordinate in the Navy Ministry and instructed that all necessary measures be taken to secure obedience. Orders were also issued to all major naval commands within Japan, directing them to dispatch their chiefs of staff to Tokyo immediately in order to receive instructions.11

[733]

The prompt action taken by the Army and Navy authorities proved, for the most part, highly effective. In the Army, where the more threatening situation prevailed, the final, unequivocal decision of the top leaders to abide by the will of the Emperor dealt a crippling blow to the smouldering plot of the young officers for a coup d'etat to block the surrender. The conspirators had predicated their plans upon unified action by the Army as a whole. Since the decision of the Army leadership clearly rendered this impossible, most of the principal plotters reluctantly abandoned the coup d'etat scheme on the afternoon of 14 August.12

Not all of the conspirators, however, were willing to bow to the leaders' decision. Two of the most fanatical-Maj. Kenji Hatanaka and Lt. Col. Jiro Shiizaki, both of the Military Affairs Bureau in the War Ministry-were determined to make a last, desperate attempt to block the surrender and force a reversal of the Imperial decision to terminate the war. They talked Lt. Col. Masataka Ida, a colleague in the Military Affairs Bureau, into joining them and also secured the promised support of two staff officers of the 1st Imperial Guards Division.13

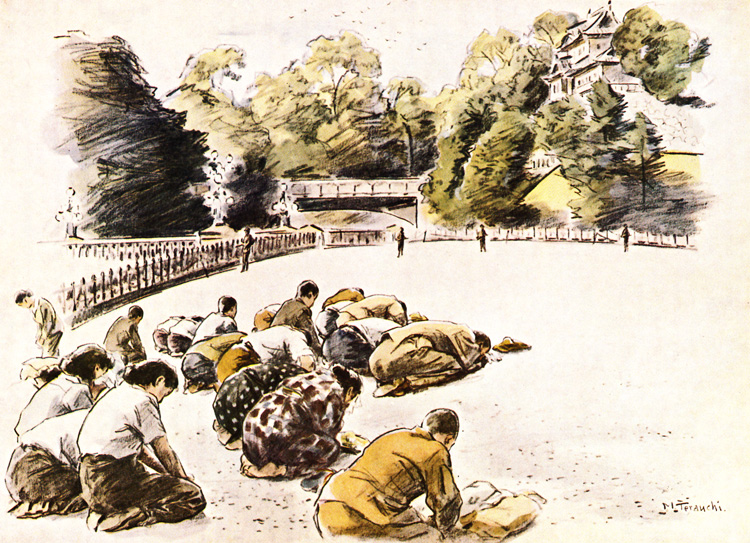

Hatanaka and Shiizaki made it their ultimate objective to prevail upon the Emperor to change his mind and forestall his scheduled broadcast on the 15th while galvanizing the Army into a united opposition to the surrender. To accomplish this, they had in mind a military government and planned first to deploy troops of the Guards Division during the night of 14-15 August to seize control of the Imperial Palace thereby insulating the Emperor. They also planned to usurp control of the central Tokyo radio station since the broadcast would end all possibility of contrary action by the Army. In case of failure, they were fully prepared for suicide.

The conspirators were ready to go into action late on the 14th. Between 2300 and midnight, Hatanaka, Shiizaki and Ida proceeded to the headquarters of the 1st Imperial Guards Division, situated close by the Northwest (Innui) gate of the Palace grounds (Plate No. 169), and met the two division staff officers who had been won over to the plot. Shiizaki and these two officers-Majs. Hidemasa Koga and Sadakichi Ishihara-immediately began planning the disposition of division troops. Shortly after midnight Shiizaki, Hatanaka and Ida gained admittance to the office of the Guards Division commander, Lt. Gen. Takeshi Mori, and

[734]

demanded that he order the division to rise against the surrender decision. If Mori's troops acted, Hatanaka declared, the Army as a whole would follow.

Mori flatly refused. The Emperor's decision was already taken, he said, and the Guards Division, particularly charged with the mission of protecting the sovereign, would under no circumstances act contrary to his will. Hatanaka declined to accept this answer as final and pressed Mori to change his mind. Ida mean while went into the adjoining office of the division chief of staff, Col. Kazuo Mizutani, and tried to persuade him to support the plot.

For some time heated discussion continued between Hatanaka and Mori. The Guards Division commander was still standing firm in his refusal to act, when another conspirator, Capt. Shigetaro Uehara of the Army Air Academy, came in and joined Hatanaka. Uehara urged Hatanaka to act speedily lest the plot fail. Hatanaka then appealed to Mori once more to give his consent, and when Mori refused, Hatanaka drew his pistol and shot the Guards commander in cold blood. At the same time, Uehara drew his sword and cut down Mori's brother-in-law, a staff officer of the Second General Army, who had been with General Mori when the conspirators appeared at the division headquarters and who at this moment attempted to intervene.

The plot now moved into high gear. Shiizaki and the two staff majors of the Guards Division had completed planning the disposition of troops, and a fake division order was drawn up over Lt. Gen. Mori's official seal to put the dispositions into effect. The order directed the bulk of the division strength to take up positions encircling the Palace grounds, while one company of the 1st Guards Infantry Regiment was to occupy the Radio Tokyo building. All communications between the Palace and the outside were to be severed, except those leading to division headquarters.14

Hatanaka, Shiizaki and Uehara did not wait for the false order to be completed. Leaving Koga and Ishihara to handle matters at division headquarters, they immediately proceeded to the Palace grounds at about 0200 and were admitted to the command post of the Palace guard detachment near the Nijubashi entrance. Two battalions of the 2d Guards Infantry Regiment under command of Col. Toyojiro Haga, the regimental commander, were currently standing guard duty. Hatanaka and Shiizaki, posing as staff officers specially assigned to the Guards Division by Imperial General Headquarters, told Haga that a division order was being issued to secure the Palace.

At 0200 the false order written by the conspirators was issued at division headquarters. Shortly thereafter an adjutant delivered it to Col. Haga at the Palace guard command post. Haga immediately issued implementing orders to his troops. All entry and egress to and from the Palace grounds were stopped at once.

This action immediately produced an apparent stroke of luck for Hatanaka and his fellow conspirators. Two cars attempting to leave through the Sakashita gate were stopped by sentries and found to be carrying State Minister Shimomura and a number of officials of the Japan Broadcasting Corporation, who had been engaged in recording the Emperor's surrender Rescript at the Imperial Household Ministry. Shimomura and those accompanying him were detained, searched and questioned.

[735]

PLATE NO. 169

Geography of Imperial Guards Uprising

[736]

Since they did not have the recording with them, Hatanaka and Shiizaki were certain that it must still be in the Imperial Household Ministry.

It was now urgent for the conspirators to find the Emperor's recordings of the Rescript in order to stop the broadcast which was scheduled for noon on the 15th. Accompanied by squads of Haga's troops, they lost no time in carrying out a frenzied search of the Household Ministry building. General Shigeru Hasunuma, chief aide-de-camp to the Emperor, and several Imperial Household officials were taken into custody and grilled, but they steadfastly refused to disclose the whereabouts of the recording. The Lord Privy Seal, Marquis Kido, and Imperial Household Minister Sotaro Ishiwata managed to escape discovery by hiding in an underground air-raid shelter beneath the Ministry. The searchers repeatedly ransacked Kido's office but failed to locate the vital recording.

By this time also, the plot was going awry in another quarter. Immediately after the assassination of his commanding officer, the Guards Division chief of staff, Col. Mizutani, and Lt. Col. Ida, who was acting in collusion with Hatanaka and Shiizaki, had proceeded to the headquarters of General Shizuichi Tanaka, Commanding General, Twelfth Area Army and Eastern District Army. Mizutani's object was to report the plot so that the Area Army might take appropriate counter-action. Ida, however, went with some hope that General Tanaka might support the uprising.

General Tanaka and his staff swiftly decided to assume direct command of the 1st Imperial Guards Division and stop the revolt. Steps were immediately taken to contact the various regiments and instruct them to disregard the false division order.15 Tanaka wished to proceed at once to the division headquarters and take command but was dissuaded from doing so by his chief of staff, who argued that he might be shot down in the darkness. It was consequently decided to wait until dawn.

Lt. Col. Ida, upon discovering that the Area Army command was entirely disinclined to support the uprising, left General Tanaka's headquarters for the Palace grounds. There, he briefly met Hatanaka and advised him that the situation was hopeless, urging that the plot forthwith be abandoned. Hatanaka, however, was not yet ready to admit failure. Ida then left the Palace grounds and proceeded to the official residence of the War Minister, where another part of the drama was unfolding.

About midnight of 14-15 August, Hatanaka temporarily suspending negotiation with Lt. Gen. Mori, had called on Lt. Col. Masahiko Takeshita, one of the leaders of the original coup d'etat plot and brother-in-law of War Minister Anami. Takeshita, with most of the other ring-leaders, had already renounced the plot, but Hatanaka now disclosed to him that he (Hatanaka) and Shiizaki intended to incite action by the Guards Division in a final effort to block the surrender. Hatanaka urged Takeshita to use his influence for the purpose of winning over War Minister Anami. Takeshita finally consented to do so if the Eastern District Army Command also supported the coup.

At about 0100, Takeshita went to the War Minister's official residence in order to report Hatanaka's plan. However, finding upon his

[737]

arrival that General Anami was preparing to commit suicide, he remained silent concerning the purpose of his visit until about an hour later when shots were heard from the direction of the Palace. Takeshita then told Anami that Hatanaka and Shiizaki were launching an armed coup with Guards Division troops in order to stop the Emperor's surrender broadcast and spur the Army to united action.

General Anami received this news with a curious and enigmatic calm. He manifested no intention of acting to put an end to the uprising or of changing his suicide plan. He merely remarked to Takeshita that General Tanaka's Twelfth Area Army would probably not join in the revolt, and that as long as the Area Army stayed quiet, the insurrection would collapse. Even when Takeshita, a short while later, relayed to Anami a telephone report that the rebels had assassinated the commander of the Imperial Guards Division, the War Minister showed no signs of taking positive action. His mind appeared absorbed with the thought of impending death.

It was at approximately 0340 that Lt. Col. Ida appeared at the War Minister's residence after conferring with Hatanaka at the Palace grounds. His intention was to lay bare the events which had transpired, but when he found General Anami ready for suicide, he too remained silent. Ida joined Anami and Takeshita in conversation and after an hour he departed.

At about 0445, Anami made his final preparations for death. Donning a white shirt given him by the Emperor, he knelt facing toward the Palace. A few moments later he plunged a dagger into his abdomen, then raised it and slashed his own throat. Col. Takeshita, who witnessed Anami's death, found two brief suicide messages. One was a 31-syllable verse expressing gratitude for the favors of the Emperor. The other read, "Confident of the everlastingness of our divine fatherland, I give my life in atonement for great wrongs."16

Meanwhile, as Anami had predicted before taking his own life, the Hatanaka-Shiizaki coup was rapidly collapsing. General Tanaka's headquarters had already succeeded in establishing telephonic contact with some units of the Guards Division, and these units promptly stopped compliance with the false division order. There was, however, the most important 2d Infantry Regiment commanded by Col. Haga still active in and around the Palace grounds, and also the 1st Infantry Regiment on reserve yet to be brought under control.

At about 04.50, General Tanaka, accompanied by his aide and an officer of his staff, drove to the headquarters of the Imperial Guards Division. There, he found the 1st Guards Infantry Regiment still preparing to move in accordance with the false division order. He immediately ordered the regimental commander to dismiss his troops and placed under arrest Maj. Ishihara, one of the two division staff officers who had acted in collusion with the plotters.

General Tanaka was now ready to tackle the confused situation prevailing in the Palace grounds. At about 0600 he proceeded to the Northwest (Inui) gate, where Col. Haga, in response to telephone instructions, met him and reported all developments in detail. After cautiously admonishing Haga, Tanaka ordered him to return his troops immediately to their normal duties. Also at this time Lt. Col. Ida, accompanied by his superior at the War Ministry, drove to the Northwest gate but Gen. Tanaka stopped them from entering the Palace

[738]

grounds. Then, with one of Haga's battalion commanders as an escort, he personally proceeded to the Obunko (Emperor's private library and temporary residence) to ensure the safety of the Imperial family. The Eastern District Army commander then hurried to the Imperial Household Ministry to set at liberty Gen. Hasunuma and other Court officials whom the rebels had confined. Gen. Tanaka accompanied by Gen. Hasunuma reported to the Throne at 0735 what had taken place in the Palace grounds. He then carefully inspected the Imperial Household Ministry buildings and other key installations to assure that his orders were carried out. He left the Sakashita gate about 0830 and returned to his headquarters.

The ill-advised plot had collapsed completely. Hatanaka, Shiizaki, Koga and Uehara signified their intention of committing suicide and were therefore allowed by Haga to remain at liberty. Koga killed himself at the Imperial Guards Division headquarters at 1300 on the 15th, Hatanaka and Shiizaki in the Imperial Palace plaza at 1400 the same day, and Uehara at the Air Academy on the night of 17-18 August.17

By 0800 on 15 August, complete order had been restored in the capital. A small force of insurgent-led troops, which had occupied the Radio Tokyo building before dawn, had already withdrawn after failing in an attempt to put a false broadcast on the air. The reckless plan of Hatanaka and Shiizaki to touch off a general Army uprising against the surrender had ended in total failure.18

The Government rigidly banned from publication all news of the uprising attempt. A War Ministry communique issued on the 15th and published the next day briefly announced the suicide of General Anami but remained silent on the circumstances surrounding it. Vice Adm. Takijiro Onishi, Vice-Chief of the Navy General Staff and organizer of the first Kamikaze corps in the Philippines, followed Anami's example on the morning of 16 August. Suicides by other high-ranking military officials continued in late August and September.19

With the collapse of the Hatanaka-Shiizaki

[739]

plot and the safe execution of the Emperor's surrender broadcast, the most critical moment had passed. There were still to be scattered instances in both the Army and Navy of action in defiance of the surrender edict, some of a fairly serious and potentially dangerous nature. However, the firm resolve of the top military leaders and the discipline of the armed forces had already proved equal to their gravest test on the fateful night of 14-15 August.

Japan now faced the many complex and difficult problems involved in the practical effectuation of the surrender. But before these could be tackled, it was first necessary to install a new government in place of the weary, struggle-worn Suzuki Cabinet.

Immediately after Suzuki's resignation on the afternoon of 15 August, the Emperor commanded Marquis Kido to recommend a new Premier. Speed was essential since General MacArthur's headquarters in the Philippines was already dispatching orders to the Japanese Government with regard to surrender arrangements. Marquis Kido therefore decided to dispense with a full advisory conference of the jushin and summoned only Baron Hiranuma, President of the Privy Council, for consultation.

Kido and Hiranuma swiftly agreed in view of the troubled domestic situation that a member of the Imperial family should be called upon to head the Cabinet. Since it was particularly vital that the nominee had the confidence of the armed forces, the choice fell upon General Prince Naruhiko Higashikuni, uncle-in-law of the Emperor, member of the Supreme War Direction Council, and former commander of the General Defense Army. The Emperor approved Kido's recommendation on the evening of the 15th, and at 1000 on the 16th Prince Higashikuni formally received the Imperial command to form a new government.20 This marked the first time that an Imperial Prince had been appointed Premier since the promulgation of the Meiji Constitution.

Marquis Kido strongly emphasized to the premier-designate the urgency of forming a cabinet which would be capable of effecting the difficult transition to peace swiftly and without incident. He pointed in particular to the nervousness of the people in the face of impending enemy occupation and the ever-present threat of rebellious action on the part of Army and Navy elements opposed to surrender. General MacArthur, he informed the Prince, was already demanding the prompt dispatch of a surrender mission to Manila.21

Messages had begun arriving from MacArthur's headquarters during the night of the 15th. The Japanese Government and Imperial General Headquarters, however, took no action in compliance until formal notification was received from the Allies at 1030 on 16 August that the final Japanese surrender offer had been accepted. The Allied note, signed by the United States Secretary of State, James F. Byrnes, directed the Japanese authorities to

[740]

order the prompt cessation of hostilities and stated that General MacArthur had been named Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers to effect the surrender.22 The note read:

You are to proceed as follows:

1. Direct prompt cessation of hostilities by Japanese forces, informing the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers of the effective date and hour of such cessation.

2. Send emissaries at once to the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers with information of the disposition of the Japanese forces and commanders, and fully empowered to make any arrangements directed by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers to enable him and his accompanying forces to arrive at the place designated by him to receive the formal surrender.

3. For the purpose of receiving such surrender and carrying it into effect, General of the Army Douglas MacArthur has been designated as the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, and he will notify the Japanese Government of the time, place and other details of the formal surrender.

The earlier radios direct from General MacArthur had specified that representatives, accompanied by competent advisors representing the Army, Navy and Air Forces, should be sent to Manila to receive instructions regarding effectuation of the surrender. The delegation was directed to travel aboard and aircraft of specified type and markings and to proceed via a designated route, leaving Sata-Misaki, on Kyushu, between 0900 and 1100 on 17 August.23 This allowed barely 24 hours in which to make preparations for the mission.

Execution of the Allied instructions was hampered almost immediately by disagreement in Imperial General Headquarters and the Foreign Office as to the exact nature of the mission. Some officials interpreted the instructions to mean that the delegates must be armed with full powers to receive and agree to the actual terms of surrender and consequently must be top representatives of the Government and High Command. Others understood them to mean that the mission would be purely preparatory for the purpose of working out technical surrender arrangements and procedures.24

Late in the afternoon of 16 August, a message was dispatched to General MacArthur's headquarters asking for a clarification of this matter and requesting more time in which to organize and prepare the mission. At the same time the Supreme Commander was notified that the Emperor, at 1600 on 16 August, had issued a "cease hostilities" order to all Japanese armed forces and was prepared to dispatch members of the Imperial family to the various combat areas to assure obedience by the field commanders. The message pointed out, however, that it might take some time for knowledge of the order to reach the front-line troops before resulting in full cessation of hostilities.25

A reply clarifying the purpose of the mission to Manila was received from the Allied Supreme Commander on the morning of 17 August. The Government and Imperial General Headquarters promptly acted to hasten the necessary preparations, but appointment of the head of the mission was further held up pending the installation of Higashikuni Cabinet.

The premier-designate had pushed the

[741]

formation of the new government at top speed, and on the afternoon of the 17th the official ceremony of installation took place in the Emperor's presence. Until General Shimomura could be summoned to Tokyo from his North China Area Army command, Prince Higashikuni himself assumed the portfolio of War Minister concurrently with the premiership Admiral Mitsumasa Yonai remained in the critical post of Navy Minister. Prince Ayamaro Konoye, in accordance with a special recommendation by Marquis Kido, entered the Cabinet as Minister without Portfolio to act as Prince Higashikuni's closest advisor. The post of Foreign Minister was given to Mr. Mamoru Shigemitsu, who had previously served in the Koiso Cabinet.26

With the new government duly installed in office, Prince Higashikuni broadcast to the nation on the evening of 17 August. He declared that his policies as Premier would conform to the desires of the Emperor as expressed in the Imperial mandate to form a Cabinet. These policies, he said, were to control the armed forces, maintain public order and surmount the national crisis, with scrupulous respect for the Constitution and the Imperial Rescript terminating the war.27

hostilities had already been taken by Imperial General Headquarters in advance of the formal order received from the Allied Powers on 16 August. On the 14th, the Navy Section of Imperial General Headquarters had ordered immediate suspension of all attack operations against the United States, Britain, China and the Soviet Union.28 The Army Section followed suit on the 15th with an order which stated:29

1. It is the intention of Imperial General Headquarters to comply with the provisions of the Imperial Rescript of 14 August 1945.

2. Until further orders are received, all Armies will continue performance of present duties, but all active attack operations will be suspended. Steps will be taken to maintain military discipline and solidarity of action. In the homeland, Korea, Sakhalin and Formosa, precautions will be taken against possible disturbances of the public peace.

Following receipt of the Allied order on 16 August, immediate steps were taken to extend the suspension of attack operations to all hostile activities. Orders sent out the same day by the Army and Navy Sections of Imperial General Headquarters directed all Army and Fleet commands to order the forces under their control to "cease hostilities forthwith." Army and Fleet commanders were ordered to report back to Imperial General Headquarters the effective dates and hours set by them for the cessation of hostilities in their respective The first steps toward actual cessation of operational areas.30

[742]

On 17 August, the Emperor personally backed up these orders with a special Rescript to the armed services. His Majesty's message, carefully worded to assuage military aversion to surrender, paid tribute to the gallantry, sacrifice and undiminished fighting spirit of the armed forces, but exhorted them to comply with the Imperial decision to conclude peace since this was necessary to assure the preservation of the national polity. The Rescript read:31

More than three years and eight months have elapsed since We declared war against the United States and Great Britain. We are deeply grateful to Our beloved soldiers and sailors for fighting gallantly in pestilential wastelands and over raging tropical seas, undeterred by every hardship.

Recently, the Soviet Union entered the war against Us, and various other factors, domestic and international, have led Us to conclude that any further continuation of hostilities would only result in increased disaster and ultimately bring destruction of the very basis of the Empire's existence. Therefore, although the fighting spirit of the Army and Navy is in no way diminished, it is Our intent to conclude peace with the United States, Britain, the Soviet Union and the Chungking Government in order to assure the preservation of Our glorious national polity.

We are sincerely grieved at the loss of many of Our loyal and brave officers and men, who have fallen in battle or died of illness. At the same time, We believe that the distinguished deeds and true loyalty of Our fighting men will embody the soul of the Japanese people for all generations.

We charge you, the members of the armed forces, to comply faithfully with Our intentions, to preserve strong solidarity, to be straightforward in your actions, to overcome every hardship, and to bear the unbearable in order to lay the foundations for the enduring life of Our nation.

On the same day that the Rescript to the armed forces was issued, three Imperial Princes left Tokyo by air as personal representatives of the Emperor to urge compliance with the surrender decision upon the major overseas commands. The envoys chosen all held military rank as officers of the Army, and they had been guaranteed safety of movement by General MacArthur's headquarters. General Prince Yasuhiko Asaka was dispatched as envoy to the headquarters of the expeditionary forces in China, Maj. Gen. Prince Haruhiko Kanin to the Southern Army, and Lt. Col. Prince Tsuneyoshi Takeda to the Kwantung Army in Manchuria. By 20 August, they had completed their missions.32

Meanwhile, on 19 August, Imperial General Headquarters had issued orders fixing 22 August as the final deadline for the cessation of all acts of hostility by Army and Navy forces in the homeland area.33 A Navy Section order issued 22 August directed the Southeast, Southwest and China Area Fleets to cease hostile acts with the least possible delay after 22 August. The same day, an Army Section order set 25 August as the final date for cessation of hostilities by all overseas Army forces.34

The Army High Command had been par-

[743]

PLATE NO. 170

Burning Regimental Flag

[744]

ticularly apprehensive with regard to the reaction of the forces in China to the surrender. The China Expeditionary Army, with a strength of about one million men, had never suffered a decisive military defeat in eight years of fighting. On about 11 August, after learning that Japan was suing for peace, General Yasutsugu Okamura, China theater commander, had addressed a strong protest against acceptance of unconditional surrender to both War Minister Anami and the Chief of the Army General Staff.35

The concern felt by the Army authorities, however, proved needless. Following the promulgation of the Imperial Rescript terminating the war, General Okamura promptly ordered the forces under his command to comply with the surrender decision. With the exception of minor elements which were under attack by Chinese Communist troops, all components of the China Expeditionary Army had ceased hostilities by 21 August.

Although delays had been anticipated, the cessation of hostilities was actually accomplished in most areas with remarkable speed. By midnight on 17 August, all Army and Navy forces in Japan and Southern Korea and all Navy forces in China and the Rabaul area had reported the end of hostile action. By 19 August, similar reports had been received from Northern Korea, the Kuriles, most sections of Manchuria, the Central Pacific islands and New Guinea. Army forces in the Rabaul area and, with some exceptions, the forces in Southeast Asia had reported by 22 August. No report, however, was received from General Yamashita's beleaguered headquarters in the mountains of northern Luzon.36

Parallel with the steps to bring about cessation of hostilities, preparations were hastily completed for the dispatch of the surrender mission to Manila. The installation of the Higashikuni Cabinet on 17 August removed one cause of delay, and in the afternoon of the same day a message from General MacArthur's headquarters clarified the nature and purpose of the mission. On the basis of this clarification, it was promptly decided that Lt. Gen. Torashiro Kawabe, Deputy-Chief of the Army General Staff, should head a delegation of sixteen members mainly representing the Army and Navy General Staffs.37

Lt. Gen. Kawabe was formally appointed by the Emperor on 18 August. By late afternoon of the same day, assembly of the data required by the Allied Supreme Commander was largely completed, and a message was dispatched to Manila informing General MacArthur's headquarters that the mission was prepared to leave the following morning.38 The itinerary received prompt approval from the Supreme Commander.

At 0611 on 19 August, the surrender mis-

[745]

sion took off from Haneda Airport, outside Tokyo, and first proceeded to the naval air base at Kisarazu on Boso Peninsula in Chiba Prefecture. There, they boarded two disarmed Navy medium bombers displaying the distinctive markings specified by General MacArthur's headquarters. The planes took off at 0707 for Ie-Shima in the Ryukyus, where the delegates were to transfer to an American aircraft for the rest of the journey to Manila.

Special precautions were taken during the initial part of the flight owing to rumors that anti-surrender elements in the Air forces might attempt to intercept and shoot the planes carrying the mission. The two aircraft took a circuitous route and flew with radios silenced.39 No mishap occurred, and they put down safely at Ie-Shima at 1240. The mission then boarded an American Army transport which reached Nichols Field near Manila at 1800 the same day.

At the airport the delegation was officially met by Maj. Gen. Charles A. Willoughby, Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2. Jeering, hostile crowds of Filipinos lined the streets to watch as a procession of military cars drove the members of the mission to their hotel. At 2100 the first conference began at the Supreme Commander's headquarters in the Manila City Hall, with Lt. Gen. Richard K. Sutherland, General MacArthur's Chief of Staff, presiding.40

The initial discussions continued for four hours, during which speedy progress was made toward the settlement of major problems. Data required by Allied headquarters with regard to the strength and disposition of Japanese Air forces, locations and condition of remaining naval vessels, condition of airfields, and other matters were submitted. Lt. Gen. Kawabe affirmed the Japanese intention to carry out faithfully all requirements fixed by the Allied Supreme Commander and expressed hope that the entry of the occupation forces into Japan could be effected smoothly and without incident.41

The conference now tackled the vital problem of the occupation time schedule. From a document handed to them at the start of the discussions, the Japanese delegates learned that General MacArthur's headquarters had already drawn up a tentative schedule which left an unexpectedly short time before the entry of the first occupation forces into Japan. This schedule called for the landing of an advance party at Atsugi Airfield on 23 August, the entry of naval forces into Tokyo Bay on the 24th, the arrival of General MacArthur at Atsugi on the 25th together with the start of the main landings of airborne troops and naval and marine forces, signature of the formal surrender instrument aboard an American battleship in Tokyo Bay on the 28th, and initial troop landings in southern Kyushu on 29-30 August.42

[746]

The Japanese delegates felt that this stringent schedule left far too little time for effecting the evacuation and disarmament of Army and Navy forces in the areas of initial occupation and for taking other precautionary measures against the occurrence of untoward incidents. Lt. Gen. Kawabe and the senior Japanese naval delegate, Rear Adm. Yokoyama, frankly stated this view to the American representatives and requested that a period of at least ten days be allowed for preparations before the entry of Allied troops. Lt. Gen. Sutherland replied that such an extended delay could not be granted, but in order to ease the difficulties on the Japanese side, he consented on behalf of the Supreme Commander to defer the arrival of the advance party at Atsugi for three days until 26 August, with the first major troop landings to be similarly held up until the 28th.43

At the second and concluding conference, which began at 1030 the following day, the Japanese delegation was handed several documents relating to the occupation and surrender procedures. The first of these was a statement of requirements covering the surrender of Japanese military forces, the entry of occupation units into the Tokyo and Kanoya areas, and logistic matters. The others were the texts of the formal surrender instrument to be signed in Tokyo Bay, of an Imperial Rescript to be issued following the surrender ceremony, and of a general order to be issued by Imperial General Headquarters simultaneously with the Rescript, commanding Japanese forces in the field to surrender to designated Allied commanders.44

The surrender parleys ended at 1215 on the 20th. Shortly thereafter, the Japanese delegation was escorted to Nichols Field for the return flight to Ie-Shima. Just before departure, however, Rear Adm. Yokoyama handed Maj. Gen. Willoughby of the American staff, a solicitation appealing to the Supreme Commander for special consideration in the enforcement of the occupation, to the traditional veneration of the Japanese for their shrines and ancestral tombs and the privacy of their homes.45 This appeal was received in the same spirit of fairness which had marked the American attitude throughout the parleys.46

In contrast to their uneventful journey to Manila, the Japanese delegates ran into bad luck on the way back to Tokyo. At Ie-Shima, where they were to transfer back to their own planes, last-minute mechanical trouble with its brakes prevented one of the two aircraft from taking off. Since, however, it was extremely vital to carry the conference data back to Tokyo without a moment's delay, Lt. Gen. Kawabe and the other principal members of the delegation decided to take off immediately aboard the remaining aircraft. The plane left Ie-Shima at 1840 on the 20th.

Through an error made in refueling at Ie-Shima, the plane suddenly ran short of gasoline as it neared its home base at Kisarazu just before midnight. The pilot quickly decided upon a forced landing in shallow water just offshore near Hamamatsu and succeeded in

[747]

bringing the plane down without serious injury to anyone aboard and without loss of the vital documents carried by the delegation. Early on the morning of 21 August, a special Army plane picked up the delegates at Hamamatsu airfield and flew them the short remaining distance to Tokyo.47

Immediately after reaching the capital, Lt. Gen. Kawabe made a full report on the results of the surrender mission to the Emperor, the Premier, and Imperial General Headquarters. With the scheduled arrival of the advance party of the Allied occupation forces only five days away, it was clear that only by superhuman effort could the necessary preparations and precautions be carried out in time to comply with the requirements fixed by General MacArthur's headquarters.

Preparations for Allied Occupation

The most pressing task facing the Japanese military authorities under the Allied directives received at Manila was the disarmament of combat units stationed in the areas of initial occupation and their evacuation outsides these areas. Only a few hours after Lt. Gen. Kawabe reported the outcome of his mission, the Army and Navy Sections of Imperial General Headquarters, on the afternoon of 21 August, issued basic orders for the execution of this requirement. Detailed implementing directives were issued the same day and on the 22nd.

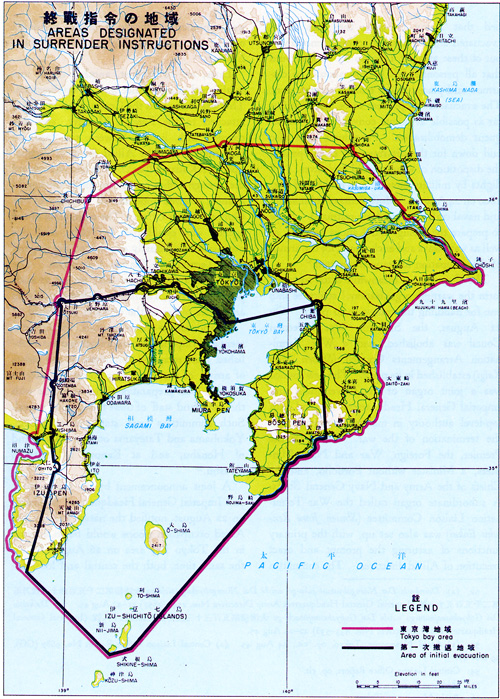

The basic orders stated that Allied forces would begin occupying the homeland on 26 August and reaffirmed the intention of Imperial General Headquarters "to insure absolute obedience to the Imperial Rescript of 14 August, to prevent the occurrence of trouble with the occupying forces, and thus to demonstrate Japan's sincerity to the world." With respect to the disarmament and evacuation of Japanese forces in the initial occupation areas, the orders established the following deadlines:

Army Forces48

1. All forces except units specially authorized will be evacuated, leaving behind their equipment, from the "area of initial evacuation" along both sides of Tokyo and Sagami Bays (Plate No. 171) by 1200 on 25 August.49

2. All forces except units specially authorized will be evacuated, leaving behind their equipment, from the Kanoya area in southern Kyushu, by 1200 on 30 August.50

Navy Forces51

1. All combat forces except the minimum required to maintain order and guard weapons dumps, supplies and military installations, will be evacuated from the Atsugi area by 1800 on 24 August, and from all other parts of the "area of initial evacuation" by 1800 on 27 August.

2. All combat forces except those required for maintenance of order and guard duty will, after disarming, be evacuated from the Kanoya area, in southern Kyushu, by 1800 on 30 August.

The implementing directives subsequently issued by Imperial General Headquarters speci-

[748]

PLATE NO. 171

Areas Designated in Surrender Instructions

[749]

fied that Army forces in the areas to be evacuated should prepare to begin movement out of these areas at 1200 on 23 August, and that all personnel left behind should be disarmed and placed under reliable commanders. The evacuated troops were to be assembled as far as possible at points convenient for subsequent demobilization. Procedures were also laid down for the disarmament of troops and the disposition of weapons and explosives. All flights by military aircraft were prohibited after 1800 on 24 August. Movements of submarines and naval craft were similarly restricted. Steps to prepare the Atsugi and Kanoya airfields, as well as waterways and anchorages, for the arrival of the occupation forces were directed.52

The Government meanwhile acted to transform the wartime organizational structure into one for handling the transition to peace. On 22 August, the Supreme War Direction Council was abolished, and a War Termination Arrangements Council (Shusen Shori Kaigi) established in its place. The new council was a joint organ of the Government and Imperial General Headquarters, invested with top-level authority in matters connected with the termination of the war. On it sat the Premier, the Foreign, War and Navy Ministers, a Minister without Portfolio, and the Chiefs of the Army and Navy General Staffs. A subordinate organ called the War Termination Liaison Committee (Shusen Jimu Ren-raku Iinkai) was also set up, with the primary functions of assuring the prompt and exact execution of Allied directives. The committee was composed of officials of various ministries under the chairmanship of the Foreign Minister.53

Later, on 26 August, another organ was established in accordance with Allied directives. This was designated the Central Liaison Office, attached to the Foreign Ministry, and was charged with liaison between the Japanese Government and the Allied forces of occupation. Mr. Katsuo Okazaki, who had represented the Foreign Office on the surrender mission to Manila, received appointment as Chief of the Central Liaison Office. The main office of the agency was established in Tokyo, and this organization gradually supplanted the original War Termination Liaison Committee. The local liaison offices were later set up at such places as Atsugi, Tachikawa, Yokohama, Kyoto and other places as the occasion demanded.54

In addition to these agencies, the Government and Imperial General Headquarters established joint reception committee at the points of arrival of the occupation forces in order to expedite local preparations and cooperate with the command staff of these forces upon arrival. Such committees were stationed at Atsugi, Yokohama and Tateyama on the main island of Honshu, and at Kanoya in southern Kyushu.55

A joint announcement by the Government and Imperial General Headquarters, published on 22 August, notified the nation at large that Allied occupation troops would begin arriving in the Tokyo Bay area on 26 August.56 At the same time, both the central and local au-

[750]

thorities took steps to calm public disquiet and apprehension caused by wild rumors that the occupying forces would commit acts of violence and brutality against the civilian population. A hasty evacuation of the coastal areas was already beginning as a result of these exaggerated fears.

To ease the public nervousness and combat rumors, the press and radio were fully employed. On 22 August, the Home Ministry announced that "all phases of the occupation by Allied troops will be peaceable" and urged the public not to "become needlessly panic-stricken" and, under no circumstances, to resort to physical force against the occupying troops.57 Governor Hirose of Tokyo Metropolis similarly urged the people to shun irresponsible rumors and maintain a discipline worthy of the nation.58 Residents of the Yokosuka area were assured that the evacuation of women and children due to fears concerning the conduct of occupation troops was totally unnecessary and that "no unpleasant incidents are expected to occur."59

While the authorities thus strove to instill confidence in the public with regard to the conduct of Allied troops, they themselves continued to be apprehensive lest hostile action by die-hard anti-surrender elements in the Japanese armed forces wreck the peaceful effectuation of the occupation. There had been ominous indications of trouble both from Kyushu, where the bulk of sea and air special-attack units were poised to meet an enemy invasion, and from Atsugi itself, which was to be the main point of entry for Allied airborne troops into the Tokyo Bay area.

The threat in these instances came from the Navy Air forces. Although the Navy Section of Imperial General Headquarters, as early as 14 August, had ordered the suspension of attack operations, Vice Adm. Matome Ugaki, Commander of the Fifth Air Fleet based on Kyushu, decided to defy the Imperial surrender decision in a final suicide attack on the enemy. Leading a formation of eleven tokko planes, he took off from Oita airfield on the afternoon of 15 August, within a few hours after the Emperor's surrender broadcast, and headed for Okinawa to attack enemy shipping. None of the aircraft returned. Ugaki, who had sent hundreds of his Kamikaze pilots into battle now realized that the only way left for him was to follow in the footsteps of his gallant airmen60

Vice Adm. Ryunosuke Kusaka, appointed to succeed Ugaki, acted speedily to prevent further trouble by hastening the separation of units from their weapons. This device obviated a repetition of acts as serious as Ugaki's, but there was a temporary breakdown of discipline and control which hampered the orderly disarmament and evacuation of units from the Kanoya area in preparation for the arrival of occupation forces.

At Atsugi, an even more threatening situation developed in the Navy's 302d Air Group. Immediately after the announcement of the surrender, extremist elements in the Group led by Capt. Yasuna Kozono, flew over Atsugi and the surrounding area in their aircraft and scattered leaflets urging continuation of the war on the ground that the surrender edict was not the true will of the Emperor but the machination of "traitors around the Throne". The extremists, numbering 83 junior officers and noncommissioned officers, did not resort to hostile acts but refused to obey orders from their superior commanders.

On 19 August Prince Takamatsu, brother

[751]

of the Emperor and a captain in the Navy, telephoned to Atsugi and personally appealed to Capt. Kozono and his followers to obey the Imperial decision. This intervention did not end the incident, however, for on 21 August the extremists seized a number of aircraft and flew them to Army airfields in Saitama Prefecture where they hoped to gain support from Army air units. They failed in this attempt, but it was not until 25 August that all members of the group had surrendered.61

As a result of the Atsugi incident, the Emperor decided on 22 August to dispatch Capt. Prince Takamatsu and Vice Adm. Prince Kuni to various naval commands on Honshu and Kyushu to reiterate the necessity of strict obedience to the surrender decision. Both princes immediately left Tokyo to carry out this mission, but the situation so improved during the next two days that they were recalled before their scheduled tours had been completed.62 The Emperor's action was nevertheless effective in helping to restore full order and discipline in the naval forces.

Meanwhile, physical preparations for the entry of the Allied occupation forces were being rushed ahead in the face of serious difficulties. On the night of 22-23 August, a typhoon struck the Kanto area, inflicting heavy damage and interrupting communications and transport vitally needed for the evacuation of troops from the occupation zone. It now appeared highly unlikely that the preparations to receive the Allied advance party could be completed by 26 August, the scheduled date of arrival. On the 24th, therefore, a message to this effect was dispatched to General MacArthur's headquarters.63

In response to the Japanese message, the Supreme Commander notified the Government and Imperial General Headquarters on 25 August that the occupation schedule would be set back an additional two days.64 This 48-hour postponement was rendered even more necessary by a second typhoon which struck western Honshu during the 25th. The delay, however, proved sufficient to enable most of the disorganization and confusion to be overcome before the entry of the occupation troops. Preparation of troop billets, requisitioning of motor vehicles, and other required steps were carried out despite a serious lack of materials and facilities.

Disarmament and Demobilization

From the moment that Japan's surrender had become final, the military authorities had recognized that the key to assuring a smooth transition from war to peace lay in the speediest possible disarmament and demobilization of the armed forces. Imperial General Headquarters had therefore begun laying the groundwork for these vital processes even before the departure of the Japanese surrender mission to Manila.

The disarmament and demobilization of such large forces, scattered over a wide area of the Pacific and the Asiatic mainland, was obviously a formidable task. In the homeland alone, there were approximately 3,655,000 men under arms, both Army and Navy.65 The

[752]

strength of Army and Navy forces overseas, including the scattered remnants left behind and isolated in such places as New Guinea, the Bismarcks and the Solomons and in the mountains of the Philippines, could only be very roughly estimated owing to the lack of up-to-date information for many areas. Actually, later investigations indicated an approximate total of 3,575,323, with the largest concentrations in China and Manchuria.66

For the homeland area, disarmament procedures could be fairly well standardized and controlled. For the overseas theaters, however, they had to be left flexible to meet varying conditions, and local commanders were allowed a wide measure of discretion.67 As far as possible, Imperial General Headquarters sought to apply the principle of self-disarmament by Japanese troops by order of their own commanders, so that the stigma of surrender would be less keenly felt by the individual soldier. This concern was manifested in similar Army and Navy Section orders issued respectively on 18 and 19 August, which stated in part:68

Military personnel and civilians attached to the armed forces, who come under the control of enemy troops following the promulgation of the Imperial Rescript, will not be regarded as prisoners of war. Nor will the surrender of weapons or any other act performed in accordance with enemy directives handed down by Japanese superiors be considered surrender.

In the homeland, full resort was made to the inactivation or transfer of military units from one place to another as a means of speedily separating personnel from their weapons. While generally effective, over-hasty measures of this nature led to some confusion in local areas, and on 9 August the Navy Section of Imperial General Headquarters issued the following directive calculated to assure orderly disarmament procedures:69

In order to eliminate all possible sources of trouble between Japanese and American forces when the enemy occupation begins, to maintain effective control over personnel, and to facilitate further arrangements of various kinds, the Commander-in-Chief, General Navy Command, will make preparations in general conformity with the following outline

1. Permission is granted to transfer and station forces as required, without regard to duties and stations assigned by existing orders.

2. Separation of forces into small units will be avoided, and so far as possible all units will be assembled promptly in suitable locations to facilitate direction and control.

3. Weapons and munitions which cannot be moved with units will not be destroyed, scattered or lost, but will be placed under the custody of necessary guards to be left behind.

4. Vessels will be anchored at their assigned mooring places; surface and undersea special-attack craft will be kept at their regular bases or close to them; and aircraft in general will be stored at their present locations. Necessary guards will be assigned.

By 26 August, two days before the scheduled arrival of the Allied advance occupation

[753]

party at Atsugi, the disarmament of Army and Navy forces in the homeland and in some overseas areas was well under way. On that date, Imperial General Headquarters, in accordance with directives from General MacArthur's headquarters, notified Army and Navy commands of procedures to be followed in negotiating the cessation of hostilities and in effecting the final transfer of weapons and equipment to Allied control.70

Parallel with the disarmament of the fighting forces, War and Navy Ministries and Imperial General Headquarters also tackled the broader problem of general demobilization. This was to be carried out in accordance with Allied directives, but even before such directives were issued, the Army and Navy authorities proceeded to draw up and disseminate basic demobilization plans so that no time would be lost. On 18 August the War Ministry issued both a general demobilization outline, approved by the Emperor, and an implementing order containing detailed basic regulation.71 Three days later, on 21 August, the Navy Ministry radioed to subordinate commands a general plan for the demobilization of naval personnel.72

Actual execution of the plans began shortly thereafter. As the program got under way, the Emperor on 25 August issued a special message to all Army and Navy personnel expressing the Imperial desire to see the demobilization carried out swiftly and in orderly fashion. The message read:73

To Our trusted soldiers and sailors on the occasion of the demobilization of the Imperial Army and Navy:

Upon due consideration of the situation, We have decided to lay down Our arms and abolish military preparations. We are overcome with emotion when We think of the precept of Our Imperial Forefathers and the loyalty so long given by Our valiant servicemen. Especially, Our grief is unbounded for the many who have fallen in battle or died of sickness.

On the occasion of demobilization, it is Our fervent wish that the program be carried out rapidly and systematically under orderly supervision, so as to give a crowning example of the perfection of the Imperial Army and Navy.

We charge you members of the armed forces, to comply with Our wishes. Turn to civilian occupations as good and loyal subjects, and by enduring hardships and overcoming difficulties, exert your full energies in the task of postwar reconstruction.

In the homeland, demobilization progressed rapidly, with some 1,500,000 men being discharged and returned to their homes by the end of August.74 Demobilization of the forces overseas, however, could be accomplished only little by little as a long and difficult program

[754]

of repatriation was carried out. The program got under way soon after the formal signing of the surrender when the Navy hospital ship Takasago Maru was dispatched to Meleon in the Caroline Islands to bring back the Japanese personnel on the island.75

At 1030 on 27 August, elements of the United States Third Fleet entered Sagami Bay in execution of first step of the delayed occupation schedule. Preparations for the reception of the Allied forces had been completed as far as was humanly possible, and in a radio address on the 26th, the newly-appointed War Minister, General Sadamu Shimomura,76 had made a final and urgent appeal to the Army to submit to the occupation quietly and without incident. He said:77

The course we must follow has clearly been indicated in the Imperial Rescript. We in the armed services have no choice but to obey reverently the Imperial will Any action against or contrary to the Imperial decision will not be condoned even though it springs from the pure Bushido spirit..... I strictly admonish you not to let yourselves be agitated by untoward incidents and not to assume a hostile attitude toward the foreigners or indulge in disorderly speech or activity..... We must behave prudently, taking into consideration the future of the nation. Do not become excited and conceal or destroy arms which are to be surrendered. This is our opportunity to display the magnificence of our nation.

Between 0828 and 1100 on 28 August, the advance party of the Allied occupation forces, consisting of about 150 men under Col. C.T. Tench, arrived at Atsugi airfield. After hearing a report by Lt. Gen. Seizo Arisue, chair man of the official reception committee, the advance party completed technical arrangements for the arrival of the main forces and issued supplementary instructions to the Japanese authorities. Col. Tench expressed satisfaction with the preliminary preparations which had been carried out in compliance with the directives of the Supreme Commander.78

On 3o August the main body of the airborne occupation forces began streaming into Atsugi in a steady procession of transport planes, while naval and marine forces simultaneously began landing at Yokosuka on the south shore of Tokyo Bay. At 1405 on 30 August, the Supreme Commander himself arrived at Atsugi to set up his headquarters on Japanese soil. The Tokyo newspaper Yomiuri-Hochi, in a story published the following day, described the scene as follows:79

As the four-engined plane landed, the waiting officers, men and newspaper reporters surged forward. The door of the plane opened, and the tall, khaki-clad figure of General MacArthur appeared. He wore dark green sun-glasses under his large, visored military cap and held a corn-cob pipe in his mouth. Calmly, he paused with one foot on the debarkation ladder to

755

look around at the welcoming party.

In his first statement to Allied and Japanese reporters, General MacArthur declared:

From Melbourne to Tokyo is a long road. It has been a long and hard road, but this looks like the pay-off. The surrender plans are going splendidly and completely according to previous arrangements. In all outlying areas, fighting has practically ceased.

In this area a week ago, there were 300,000 troops which have been disarmed and demobilized. The Japanese seem to be acting in complete good faith. There is every hope of the success of the capitulation without undue friction and without unnecessary bloodshed.

Every newspaper in Japan printed illustrated accounts of the General's arrival at Atsugi. The man who for more than three years had waged a relentless counteroffensive against the Japanese armies in the Southwest Pacific and who now was to accept and conclude the surrender, thus made his first appearance before the Japanese people.

Immediately after his arrival, MacArthur proceeded to Yokohama, accompanied by Lt. Gen. Robert L. Eichelberger, Commander of the United States Eighth Army, who had arrived earlier in the day. The party drove some 20 miles eastward through peaceful, farming country and silent, war-devastated towns. The Supreme Commander set up his headquarters provisionally in the Yokohama Customs House. The headquarters of the American Eighth Army and the Far East Air Force also had been established in the same city, and representatives of the United States Pacific Fleet were attached to Supreme Commander's headquarters.80

In order to facilitate rapid liaison, various Japanese agencies were established in the Kanagawa Government Building adjacent to the headquarters of the Supreme Commander. They included the Yokohama District Reception Committee (later the Yokohama Liaison Office), the Imperial General Headquarters Liaison Committee and the office of the Governor of Kanagawa Prefecture.

Occupation forces arrived in ever-increasing numbers by land, sea and air until important cities and major military installations were under Allied control. The occupation of Tokyo itself was not carried out until 8 September, when some 8,000 troops of the First Cavalry Division moved into the capital in orderly fashion. Up to this time, traces of uneasiness had lingered in the minds of the general populace, but the occupation of the capital without incident did much to ease tension. The nation as a whole was deeply impressed when it discovered that the occupation troops, from whom ill-treatment and excesses had been feared, were well-disciplined and under enlightened leadership. In particular, Lt. Gen. Eichelberger's order of 9 September placing the Imperial Palace, temples, shrines and private dwellings "off limits" to occupation forces was gratefully welcomed by the citizens.81

Scattered incidents of a minor character were reported as contact between the occupation forces and the Japanese Government and people became more frequent. On the whole, however, the general public was submissive, and its trust in the occupation gradually deepened. Cooperation in all quarters improved as the Japanese came to know American soldiers as individuals and recognized the efficiency and discipline with which their work was carried

[756]

out. The words of General MacArthur at Atsugi were proving prophetic.