CHAPTER XV

BATTLE ON LUZON

Launching of the American Invasion

At dawn on 9 January, three days after the appearance of the first Allied naval elements in Lingayen Gulf, outposts of the 23d Division observed two vast transport groups with a total of nearly 100 ships maneuvering into position off the southern and southeastern sectors of the gulf coast.1 While naval units raked the shore with intense covering fire, landing craft loaded with assault troops began moving in toward the beaches. The American invasion of Luzon was under way.

By 1040 Tokyo time (0940 Philippine time) the assault waves of an estimated total enemy force of not less than one armored division and two infantry divisions were ashore in the San Fabian and Lingayen sectors.2 Small outpost detachments of the 23d Division in these sectors made little or no attempt to defend the beaches against the overwhelming enemy assault, falling back to prepared inland positions after destroying key bridges near the landing points.

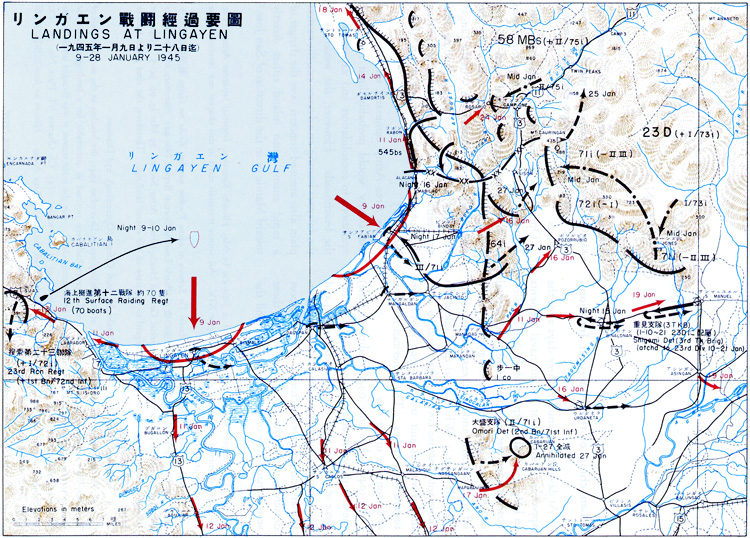

Opposition during the first day was con sequently limited to harrassing fire thrown into the San Fabian beachhead first from mortars and then from artillery emplaced along the ridges back of the coastal plain.3 In the Lingayen sector, where a major enemy landing had not been anticipated, the Japanese dispositions did not permit even artillery opposition.4 (Plate No. 111)

The Area Army command estimated that the enemy would probably limit his initial operations to consolidation and expansion of the beachheads. However, the weakness of the defenses barring an advance into the central plain also aroused concern over the danger of a rapid enemy push inland either directly toward Manila or in the direction of San Jose.5

[467]

PLATE NO. 111

Landings at Lingayen, 9-28 January 1945

[468]

This danger was aggravated by the fact that the 2d Armored Division, due to the destruction of the highway bridge at Calumpit, could not without serious risk execute the Area Army order of 8 January directing the movement of its main strength from Cabanatuan to Tarlac.6

To cope with this situation, the Area Army on 9 January countermanded its previous order to the 2d Armored Division and instead instructed the division to move its main strength north to the line of the Agno River in the vicinity of Tayug.7 General Yamashita's plan was now to employ the division in a counterattack from the north flank if the enemy over-extended himself by too rapid an advance inland. If such an opportunity did not arise, the division's role was to become essentially defensive.

Back in Lingayen Gulf, the night of 9-10 January witnessed a determined but shortlived effort by the 12th Surface Raiding Regiment, based at Port Sual, to disrupt further enemy landing operations by an all-out suicide boat attack on ships standing off the beachhead areas. The full operational strength of the regiment, about 70 boats, sortied at midnight. Profiting from the element of surprise, the small explosive-laden craft stole in undetected to launch an attack of about two hours' duration. Although substantial damage was believed inflicted, nearly all the participating boats were lost in the attack, and the 12th Surface Raiding Regiment was rendered incapable of further operations.8

Despite this fleeting interference, the enemy continued to pour troops and supplies ashore. By 11 January the forces in the San Fabian and Lingayen beachheads had effected a juncture and were firmly in control of the coastal area extending from a point just south of Rabon to the mouth of the Agno River, west of Lingayen. At the same time, advance elements of the enemy left wing forces, supported by armor, were already starting to probe the 23d Division's first line defenses to the east of San Fabian.9

Developments elsewhere had meanwhile precipitated fresh debate in Area Army head-quarters with regard to basic tactical policy. The 19-20 December plans called for a long-term delaying campaign in which the Area Army would avoid a large-scale counteroffensive except in the most favorable circumstances. However, on 9-10 January, just as the invasion was beginning, reports reached Baguio from various districts in northern Luzon to the effect that intensified guerrilla activities and enemy air attacks had virtually halted the collection and movement of essential food reserves into the key defense positions in the Baguio-

[469]

Mankayan-Bambang triangle.

This obviously presented a serious threat to the Area Army plan of protracted resistance in the mountains of northern Luzon. So critical was the view taken by a majority of the staff that, on 10 January, recommendations were drawn up for submission to the Area Army Commander and Chief of Staff, urging that the policy of long-term delay be scrapped in favor of launching an early counteroffensive with maximum forces. These recommendations were placed before General Yamashita and Lt. Gen. Muto on 11 January.

After urgent consultations with Lt. Gen. Muto and Maj. Gen. Haruo Konuma, Deputy-Chief of Staff, the Area Army Commander firmly ruled against this proposal. His decision rested on two major grounds. First, the enemy's cautious development of the beachhead before starting any advance inland did not appear likely to create a situation in the near future, in which a large-scale counteroffensive could be mounted with reasonable chances of success. Second, although a shortage of food supplies would admittedly limit the Area Army's ability to wage a long-term defensive campaign, such a campaign still appeared to be the only feasible method of achieving the over-all strategic objective of delay.10

In line with General Yamashita's decision, the plan to move the main strength of the 2d Armored Division to the Tayug sector for a possible counterattack against the flank-of an enemy thrust inland was now definitely abandoned. The Area Army, by a new order is sued on the 11th, directed the division to as semble its main strength as speedily as possible at Lupao, about eight miles northwest of San Jose.11 At the same time, the Shimbu Group commander was ordered to hasten the movement of the 105th Division main strength from the area east of Manila to Cabanatuan, the first stage of its projected transfer to the northern area.12

While firmly against risking a major counter offensive, General Yamashita nevertheless felt that limited offensive action against the beachhead would not only give his forces the advantage of the initiative but provide the most effective means of delaying the enemy's advance inland.13 This plan was studied by the Area Army staff on 11-12 January, and on the 13th Lt. Gen. Muto drove to the 23d Division command post east of Sison with an order directing the division to execute a strong raiding attack against the San Fabian-Alacan sector of the beachhead during the night of 16-17 January.14 The primary objective was to effect maximum destruction of enemy weapons, supplies and key base installations.

On 14 January Lt. Gen. Fukutaro Nishiyama, 23d Division commander, issued an implementing order laying down the task organization and plan of attack. The 58th Independent Mixed Brigade and the 71st and 72d Infantry Regiments were each directed to organize a small, streamlined "suicide" raiding unit of hand-picked troops heavily armed with

[470]

automatic weapons and reinforced by demolition squads. A fourth unit made up of a mobile infantry company and medium tank company was to be drawn from the Shigemi Detachment of the 2d Armored Division, now under 23d Division control.15 These units were to penetrate the enemy beachhead perimeter simultaneously at different points between 0200 and 0400 on 17 January. After swiftly accomplishing their missions, they were to withdraw.16

From the first, however, the plan went awry. Serious enemy penetrations of the 23d Division first line positions on 15-16 January so hampered preparations for the attack that the 72d Infantry raiding unit was finally unable to participate. Another serious setback occurred during the night of 15-16 January, when the tank-infantry task unit of the Shigemi Detachment, moving up toward its assigned line of departure at Manaoag, encountered an enemy force just west of Binalonan and was compelled to withdraw eastward after a sharp engagement.

These developments left only two of the four raiding units called for in the attack plan capable of executing the operation. The attack was was nevertheless launched at the scheduled time, with one raiding unit from the 58th Independent Mixed Brigade striking from the north toward Alacan, and the other from the 71st Infantry infiltrating toward San Fabian from the southeast. Both units penetrated almost to their objectives and succeeded in destroying some enemy weapons and equipment before heavy losses forced them to retire.17 Due to its small scale, however, the operation had little effect toward impeding the enemy advance.

After this abortive effort, the 23d Division settled down to a stubborn defense of its prepared positions, limiting offensive action to small-scale night raids. The first-line defenses, however, had already been pierced at various points, and they now began to crumble rapidly under heavy and relentless ground, air and artillery assault. On 24 January, the Area Army finally recognized that a further defense of these positions was impossible and ordered the 23d Division to pull back the remaining strength of its forward elements to the secondary defense positions in the mountains southwest of Baguio.18

[471]

PLATE NO. 112

Antitank Suicide Unit, Lingayen Gulf

[472]

The initial fighting had been costly. The 64th Infantry, when it began infiltrating to the rear on 27 January, was reduced to about one-third its original strength.19 The Omori Detachment (2d Battalion, reinf., 71st Infantry) had been entirely wiped out in the defense of the Cabaruan Hill positions on the south flank. The 3d Battalion, 72d Infantry, had been reduced to less than half-strength by the losses incurred during the raid on San Fabian. The 23d Reconnaissance Regiment (reinforced by the 1st Battalion, 71st Infantry) had been driven into the Zambales Mountains behind Sual shortly after the enemy landing and was lost to the 23d Division for subsequent operations. The 58th Independent Mixed Brigade to the north had suffered less severely, but its forward positions in the southern part of the brigade sector had been breached, forcing a withdrawal to secondary positions north of the Damortis-Rosario road.

The close of January found the 23d Division and attached forces closely engaged all along the second line of defensive positions guarding the southwestern entrance to Baguio, heart of the northern defense bastion.

Developments had meanwhile borne out the Area Army's estimate of probable enemy strategy. The invasion forces had unleashed two powerful drives from the beachhead-one aimed south toward Clark Field and Manila, the other directed east and southeast toward the key routes of access to the northern bastion from the central Luzon plain. These routes were the Villa Verde Trail, winding northeast from San Nicolas, and Highway 5, the main artery running north from San Jose over Balete Pass.

Of the two enemy drives, the second was viewed by the Area Army command as the more immediate and dangerous threat. From the strategic standpoint, seizure of either of the key routes would place the enemy in position to launch an early thrust into the northern bastion from the south, seriously jeopardizing the entire Area Army plan for a protracted defense of the northern Luzon area.

San Jose, which seemed certain to be a major enemy objective, was vitally important for other reasons as well. First, a large volume of supplies transported north from Manila had piled up at the San Jose railhead, whence its further movement into the northern bastion was proceeding slowly owing to inadequate motor transport and enemy air interference. It was therefore essential to hold San Jose until these urgently needed supplies could be moved north.

Second, there was the danger that a swift enemy penetration to the San Jose area would block execution of the plan to strengthen the defenses of the northern sector by shifting the 105th Division main strength up from the Manila area. On 15 January, when strong enemy elements broke through the 23d Division forward line into the sector northeast of Manaoag, signalling the start of the eastward push, the 105th Division had not yet completed the first stage of its northward movement to Cabanatuan.

The enemy breakthrough on 15 January spurred the Area Army command into swift action. An order issued the same day directed the 2d Armored Division, which had completed its concentration at Lupao, to advance immediately to the Tayug sector. Upon arrival, the division was to assume command of 10th Division elements already disposed north of Tayug and in the Triangle Hill sector to

[473]

the South,20 and the armored division itself was instructed to take up positions astride the trail north of San Nicolas and on both sides of the Ambayabang River. The mission of the combined forces was "to divert and contain" an enemy force attacking eastward from the beachhead.21

By the same order, the Area Army directed the main body of the 10th Division, which had completed its assembly in the San Jose area only about a week earlier, to occupy positions guarding the immediate approaches to San Jose. The division was to hold off an enemy attack while the 105th Division carried out its displacement through San Jose and occupied new positions to the north.22

A separate Area Army order dispatched the same day to the Shimbu Group stipulated that the 105th Division, upon reaching Cabanatuan, would pass under direct Area Army command. The division was directed to move its troops on from Cabanatuan to the north as speedily as possible and occupy positions behind the 10th Division at Minuli and north of Carranglan.23

Meanwhile, the Shigemi Detachment was all that stood between the enemy and Tayug, through which the 2d Armored Division was to move to its newly-assigned positions north of San Nicolas. To hold up the enemy advance until this move was completed, the Area Army ordered the detachment, through the 23d Division, to advance its main strength from San Manuel to Binalonan and defend that town to the last man.24 Already at Binalonan were the remnants of the small armored task unit which had been beaten back by the enemy on the night of 15-16 January as it was moving up toward Manaoag for the raiding attack on San Fabian.

Before the main strength of the Shigemi Detachment had time to advance from San Manuel, however, the task unit in Binalonan was driven out by enemy forces which occupied the town on 18 January. The next day the enemy drove on toward San Manuel under powerful air cover. The Shigemi Detachment tried to stem this drive by strong resistance east of Binalonan but was forced to fall back on San Manuel, where it dug in for a desperate suicide stand.25 (Plate No. 113)

The Area Army had meanwhile learned of two facts which further upset its calculations. The 2d Armored Division, after a preparatory reconnaissance of the area north of San Nicolas, reported back to Area Army headquarters at Baguio that the Villa Verde Trail was impassable to vehicular traffic. Since the division, if it occupied the positions directed by the Area Army on 15 January, would have to depend exclusively on this trail as its supply line from the rear and eventual route of withdrawal into the northern bastion, a change in plan was obviously necessary.

[474]

Even more serious was the belated discovery that the 10th Division, which the Area Army believed to be guarding the approaches to San Jose, had in fact withdrawn northward to take up positions near Minuli and north of Carranglan. This mix-up, the result of which was to leave San Jose virtually undefended, came about through the following sequence of events.

Under the Area Army plans of 19-20 December, the 10th Division had been assigned to defense of the San Jose-Umingan-Natividad line.26 It was to fulfill this mission with approximately two-thirds of its normal strength, the 39th Infantry Regiment and supporting elements of division troops having been transferred to Manila Defense Force command for the reinforcement of Bataan. Immediately afterwards, however, the strength available to the division was further reduced by the Area Army's sudden decision to divert the 10th Infantry Regiment to northern Luzon for employment in defense of the Cagayan Valley. This left the division with but five infantry battalions, plus the bulk of division supporting troops, to organize defensive positions over a front of more than 22 miles.27

In addition to the excessive length of the projected line, reconnaissance of the terrain convinced the division staff that the open country and relatively low hill features present in the area would not permit the organization of sufficiently strong positions. These objections. however, had not yet been communicated to Area Army headquarters by the time the main elements of the division completed their assembly in the San Jose area just prior to the enemy landings on Lingayen Gulf.

At this juncture, Maj. Shigeharu Asaeda, operations officer of the Area Army staff, visited San Jose to inspect defensive preparations in the 10th Division sector. The division com mand promptly seized the opportunity to point out that the reduced troop strength at its disposal, coupled with the unfavorable nature of the terrain, made impossible a strong defensive organization of the San Jose-Umingan-Nati-Umingan-Nati line. As an alternative, the division proposed to organize its main positions farther back in the mountainous terrain close to the vital passes to the north.

Inability to establish communications con tact with Area Army headquarters at Baguio prevented Maj. Asaeda from obtaining immediate approval of this proposal. However, he was convinced that it would encounter no objection from the Area Army command, and at the same time the need for action was so urgent that he advised the division commander to begin moving his main strength immediately northward to organize positions in the vicinity of Minuli and north of Carranglan. A division order on to January initiated this movement.28

On 15 January, when the Area Army ordered the 10th Division to secure the approaches to San Jose, it was still unaware of the actual situation. By the 17th, however, Maj. Asaeda had succeeded in communicating the gist of

[475]

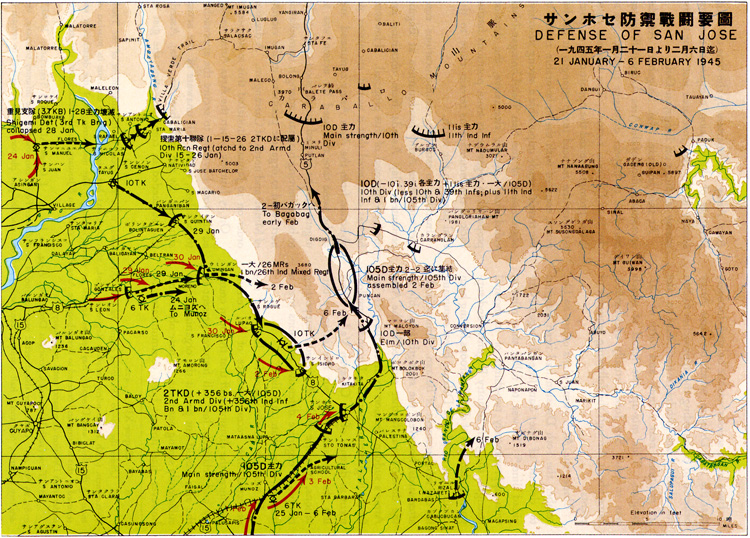

PLATE NO. 113

Defense of San Jose, 21 January-6 February 1945

[476]

his action to Area Army headquarters, and he was immediately ordered to return to Baguio by air to make a full report. Only upon his arrival from Bambang the following day did General Yamashita and his staff learn in detail of the new dispositions of the 10th Division.29

It was now doubly clear that the Area Army orders of 15 January must be drastically modified. On the one hand, the impassable condition of the Villa Verde Trail ruled out the previous plan to station the 2d Armored Division north of San Nicolas. On the other hand, the disclosure that San Jose had been left undefended except by a small residual force of the 10th Division made imperative new dispositions to secure that key point while the defense of the passes to the north was being strengthened.

General Yamashita decided that the only feasible course under these circumstances was to alter the deployment of the 2d Armored Division so as to throw it across the enemy line of advance toward San Jose for a series of frontal delaying actions. At the same time, the plan to move the entire main strength of the 105th Division north to defend the passes was modified to provide for the retention of two infantry battalions in the San Jose area to reinforce the 2d Armored Division and the residual elements of the 10th Division. On 20 January these decisions were implemented by an Area Army order, substantially as follows:30

1. The 2d Armored Division will deploy its main strength on the Tayug-Triangle Hill line and an element in the vicinity of Munoz. It will occupy positions in these sectors and endeavor to destroy the strength of enemy forces attacking from the Lingayen area across the central Luzon plain, especially in the direction of San Jose.

2. The main strength of the 10th Division will occupy positions in the vicinity of Minuli, north of Carranglan, and north of Gadeng, and will prepare both to defend these positions against an enemy attack from San Jose in the direction of Bambang and to counterattack toward San Jose. A strong element of the division will remain in positions just north of San Jose and check an enemy advance toward that point. A further element will be stationed in the Bambang area and secure that district. Division elements in the Tayug and Triangle Hill sectors will remain attached to the 2d Armored Division.

3. The main body of the south Division will advance north and assemble in the area south of Minuli as speedily as possible. One infantry battalion of the division will be placed under 2d Armored Division command at San Jose; and one infantry battalion will be transferred to 10th Division command to strengthen the advance positions just north of San Jose.

Steps to effect the new dispositions had barely started when enemy advance patrols on 21 January began probing the defenses set up by the Shigemi Detachment in and around San Manuel.31 Despite relatively flat terrain and inadequate infantry strength, advance prepara tion of the ground had enabled the detachment to dig itself in firmly for a suicide defense of the town. Artillery positions were located on high ground immediately to the northwest, covering the road from Binalonan. The greater portion of the detachment's tanks (7th Tank Regiment less 2d Company had been convert ed into stationary, fortified pill-boxes emplaced at key points around the perimeter of

[477]

the town.32 Remaining tanks were held inside the town as mobile reserve together with the bulk of the infantry.33

The decisive phase of the battle for San Manuel began on 24 January when the enemy launched heavy and simultaneous attacks from both north and south. Although the defending forces inflicted heavy losses, the northern prong of the attack penetrated the detachment perimeter and gave the enemy a foothold inside the town. Fierce fighting continued for four more days, culminating in a final desperate counterattacks by the remnants of the Shigemi force on 27-28 January. The collapse of this attack ended all resistance. Only seven tanks and 400 troops of the detachment forces which had defended the San Manuel area succeeded in escaping to join the 10th Reconnaissance Regiment north of San Nicolas.34

Meanwhile, a new menace to San Jose had become apparent. On the left flank of the main enemy drive toward Manila, which had already enveloped Tarlac and Victoria, eight miles northeast of Tarlac, on 21 January, enemy tank-infantry patrols had begun probing northeastward in the direction of Guimba and Munoz. This appeared to foreshadow a move to outflank the 2d Armored Division's main positions on the Tayug-Triangle Hill line and strike at San Jose from the southwest. The armored division, in compliance with the Area Army order of 20 January, had already shifted the 6th Tank Regiment (less two companies), reinf. to the Munoz sector, but this force was all that stood in the way of the new enemy threat.35

The seriousness of the threat was only too clear. The 2d Armored Division main strength in the Tayug-Triangle Hill area was in danger of being cut off from its sole remaining escape route into the northern bastion via San Jose and Highway 5. Further, the 105th Division was just completing its movement through Cabanatuan on 25 January and faced the pros pect of having its route northward barred by the enemy.

To meet the new situation, the Area Army on 26 January again ordered a change in the dispositions of the 2d Armored Division. Lt. Gen. Iwanaka was directed to pull back all remaining division strength from the Tayug-Umingan and Triangle Hill sectors with the exception of small outpost forces to be left at Gonzales and Umingan to delay an enemy ad vance from the northwest. The division was now to concentrate the bulk of its forces in a triangular-shaped area bounded by Lupao, Munoz and Rizal, with main positions on

[478]

Highway 8 between Lupao and San Jose and Highway 5 between Munoz and San Jose.36

These new dispositions had barely been effected when the enemy began attacking toward San Jose from both northwest and southwest. On 29 January enemy elements swept around the outpost force at Gonzales (Omuro Detach ment) and cut its withdrawal route to Umingan, forcing the detachment to withdraw through the hills after destroying most of its tanks and all of its mechanized artillery.37 The force at Umingan, one infantry battalion of the 26th Independent Mixed Regiment,38 held out until 2 February, when it was finally compelled to retreat eastward.

Meanwhile, on the Munoz front southwest of San Jose, a battle even fiercer than that fought at San Manuel was in progress. The Ida Detachment had just occupied its positions in this sector on 25 January when the enemy began preliminary attacks to probe the detachment defenses.39 Following these attacks, powerful enemy forces launched a full-scale assault on Munoz from the southwest on 1 February.

As at San Manuel, the Ida Detachment had entrenched itself in strong defensive positions with a large proportion of its tanks dug-in and reinforced to supplement the regular artillery. So firm was its resistance that the enemy assault made no progress on 1 and 2 February. On the 3rd, however, enemy forces by-passed Munoz on the southeast and cut in behind the Ida Detachment to sever Highway 5 in the vicinity of the General Luzon Agricultural School, between Munoz and Santo Tomas. The enemy then drove on up the highway toward San Jose. Antitank gun emplacements a short distance southwest of the town succeeded in stemming this advance, but enemy elements again swung around the Japanese positions to push into San Jose on 4 February. By the 6th, Highway 5 from the Agricultural School to San Jose was entirely in enemy hands.

The Ida Detachment cut off at Munoz had meanwhile been battling fiercely to hold its positions under renewed enemy attack. Col. Kumpei Ida, the detachment commander. had already been killed in action, and enemy artillery had poured into the Japanese positions as much as 15,000 rounds of fire in a single day.40 By 6 February, however, the enemy had succeeded in gaining possession of only a portion of the town.

[479]

PLATE NO. 114

Facsimile of Fourteenth Area Army Operations Order No. A-434, 20 January 1945

[480]

PLATE NO. 115

Facsimile of Fourteenth Area Army Operations Order No. A-384, 11 January 1945

[481]

Under cover of the delaying actions fought by the 2d Armored Division, the main strength of the 105th Division had successfully slipped past San Jose prior to its capture by the enemy and reassembled along Highway 5 to the south of the main positions of the 10th Division.41 On 4 February, therefore, the Area Army dispatched an order to the 2d Armored Division to break off action and withdraw through Balete Pass to Dupax for a period of rest and regrouping.42

This order actually did not reach 2d Armored Division headquarters until 6 February due to communications failure, but even at the time it was issued, the enemy seizure of San Jose had already sealed the escape route of the division forces still battling at Munoz and along Highway 8 in the Lupao-San Isidro area.43 These forces now had but two alternatives; either to attempt to break through the enemy blocking their road of retreat, or to destroy their remaining tanks and mechanized equipment and withdraw cross-country into the northern hills.

The Ida Detachment chose to attempt a break-through. Covered by a diversionary attack, the remaining strength of the detachment pulled out of Munoz with what armor still was mobile at about midnight on the 6th and headed up Highway 5 toward San Jose.

The attempt, however, was soon discovered. Between the Agricultural School and Santo Tomas, enemy artillery, antitank guns and automatic weapons raked the column with murderous fire which inflicted heavy casualties and destroyed virtually all tanks, trucks and mechanized artillery. Surviving personnel destroyed what vehicles remained and retreated off the highway to infiltrate around San Jose toward the advance positions of the 10th Division.

The 10th Tank Regiment and other 2d Armored Division elements defending Lupao and San Isidro, to the northwest of San Jose, decided against a similar break-through attempt. Destroying all tanks and mechanized equipment not already lost as a result of increasingly severe enemy attacks, the personnel of these units withdrew northeast from Highway 8 to make their way over the hills into the northern bastion.

By delaying the enemy's seizure of San Jose, the 2d Armored Division had successfully covered the transfer of the 105th Division to the north and the removal from San Jose of the bulk of supplies accumulated there. The cost, however, had been high. Of approximately 200 tanks which the 2d Armored Division possessed at the time of the Lingayen landings, 180 had been lost, together with

[482]

corresponding proportions of the division's artillery and mechanized transport. About 2,000 division troops had lost their lives.44 As an armored force, the division had been destroyed.

Simultaneously with the enemy's crushing offensive along the northern rim of the central plain toward San Jose, his right wing forces to the west drove rapidly southward from the Lingayen beachhead toward Clark Field and Manila. Inadequate troop strength had forced General Yamashita to leave the area directly to the south of Lingayen Gulf virtually undefended. The enemy's advance consequently was impeded only by demolitions carried out by retreating Japanese patrols. By 21 January Tarlac had been overrun, and the enemy pushed on toward the outer defenses of the Clark Field sector in the vicinity of Bamban.

To deny the enemy the use of the vital airfields in this sector, Fourteenth Area Army had planned to organize the mountainous terrain immediately flanking Clark Field on the west and northwest as one of the three major defense strongpoints on Luzon. Right up until the Lingayen invasion, however, execution of this plan had been hampered by two factors. First, no unified command had been set up over the large number of Army and Navy Air force base personnel stationed in the area.45 Second, Fourteenth Area Army had not been able to strengthen these forces with adequate numbers of regular ground combat troops.

Not until after General MacArthur's forces swarmed ashore in the Lingayen area was General Yamashita finally able to remedy the anomalous command situation. On 8 January, the day before the invasion, Maj. Gen. Rikichi Tsukada, commander of the 1st Airborne Raiding Group, had arrived at Clark Field from Japan with his headquarters. This at last made available a ranking general officer compe tent to direct ground operations.46 On 11 January, General Yamashita placed Maj. Gen. Tsukada in command of all Army and Navy forces in west-central Luzon embracing not only the Clark Field area but almost all of Bataan Peninsula.47 The mission assigned to these forces was:48

....to check an anticipated penetration of the Clark Field sector, facilitate the operations of the air forces as far as possible, and as a last resort hinder enemy utilization of the airfields by operating from the strongpoint west of Clark Field.

In the Clark sector, Maj. Gen. Tsukada found himself in command of a heterogeneous collection of forces aggregating about 30,000 men. The 2d Mobile Infantry Regiment (less one battalion) of the 2d Armored Division and the 2d Glider Infantry Regiment were the only

[483]

regular infantry units. The remainder consisted mainly of Army and Navy airfield battalions, antiaircaft units, and miscellaneous base and service forces. Some of the base and service troops had been organized into provisional combat units.49

The fact that no Japanese forces of significant size stood in the way of an enemy drive south from Lingayen to the Clark Field area made it apparent that time was of the essence. Maj. Gen. Tsukada immediately ordered his troops to pour all their energies into the completion of defensive preparations. The formation of provisional combat units was hastened. Automatic weapons were dismounted from the numerous disabled aircraft littering the Clark Field strips and were emplaced in defensive positions to overcome the shortage of organic artillery. In the rugged mountain terrain to the west, work was accelerated on cave and trench positions.

On 17 January Maj. Gen. Tsukada ordered final dispositions to meet an enemy attack. All available Army combat units, regular and provisional, were tactically organized into four detachments with an aggregate strength of about 8,000 troops. All the naval forces, totalling about 15,000, remained integrated under the immediate command of Rear Adm. Ushie Sugimoto, 26th Air Flotilla commander. The remaining 7,000 Army service troops were placed under Maj. Gen. Tsukada's direct command. The composition of the four Army detachments was as follows:50

Takayama Detachment

Hq, 2d Mobile Infantry Regt.

2d Bn, 2d Mobile Infantry Regt.

132d, 137th Airfield Btu.

25th Ind. Antitank Bn.

6th Btry., 2d Mobile Arty. Regt.

Misc. minor units

Eguchi Detachment

Hq, 10th Air Sector Unit

31st, 99th, 150th, 151st, 152d Airfield Bns.

Shibasaki Prov. Infantry Bn.

84th Field Antiaircraft Arty Bn.

Misc. minor units

Takaya Detachment

Hq, 2d Glider Infantry Regt.

2d Glider Infantry Regt.

Yanagimoto Detachment

Hq, 3d Bn., 2d Mobile Infantry Regt.

3d Bn., 2d Mobile Infantry Regt.

8th Ind. Tank Co.

Maj. Gen. Tsukada assigned all but one of

[484]

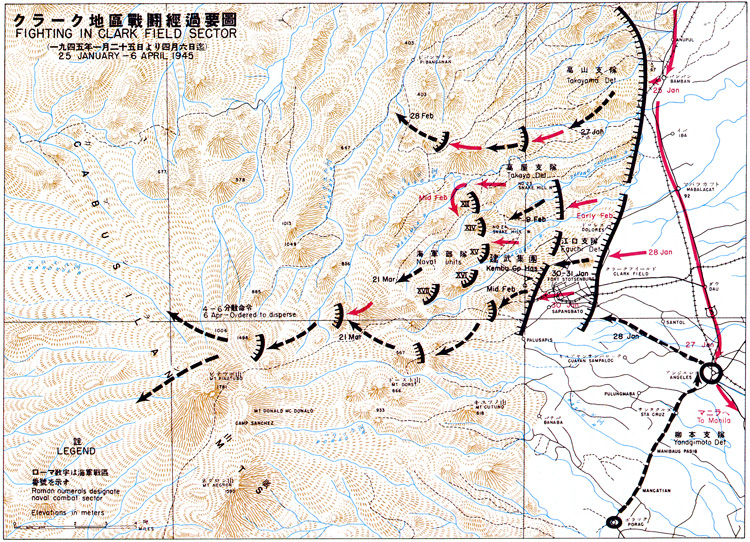

PLATE NO. 116

Fighting in Clark Field Sector, 25 January-6 April 1945

[485]

the Army detachments to the defense of his first and second-line positions. These positions faced east toward Highway 3, with the northern anchor in the hills west of Bamban and the south flank anchored in the vicinity of Sapangb ato and Fort Stotsenburg. (Plate No. 116) The Takayama Detachment was deployed in the northern sector with its main strength in the forward hill positions overlooking Bamban. To the south, elements of the Eguchi Detachment occupied a forward line running through Dolores and Clark Field to a point southeast of Sapangbato, while the main strength of the detachment held strong mountain positions north and west of Fort Stotsenburg. The Takaya Detachment was deployed in the center of the second-line defenses. The Yanagimoto Detachment, not assigned to fixed positions, held its mobile units at Angeles and Porac in readiness to move against an enemy paratroop landing on the south flank of the Clark Field defenses.51

Rear Adm. Sugimoto's naval forces were assigned to the defense of positions in the rear of the two forward lines he'd by the Takayama, Eguchi and Takaya Detachments. Organized into five combat sectors, these forces dug themselves in on commanding heights to the northwest of Fort Stotsenburg.52 While last-minute battle preparations were in progress, Fourteenth Area Army issued an order designating the forces under Maj. Gen. Tsukada's command as the Kembu Group.53

The enemy assault on the Clark Field sector defenses was not long in developing. On 22 January, the day after the fall of Tarlac, outpost patrols of the Takayama Detachment engaged in demolition work along the highway from Tarlac to Bamban were attacked by enemy spearhead elements and forced to withdraw southward. On the 23d the enemy invested Bamban itself and began probing the main defenses of the Takayama Detachment to the west of Highway 3.

The first major enemy attack on these defenses was launched on 25 January. The Takayama Detachment fought stubbornly in defense of each hill mass, but after two days of severe combat the detachment was forced to pull back toward its second-line positions.54

Other enemy forces had meanwhile driven on southward along Highway 3 to seize Mabalacat and Angeles. As this advance developed, the Yanagimoto Detachment had pulled back its elements from Porac and was preparing to engage the enemy when it received orders from Maj. Gen. Tsukada to evacuate Angeles and move into the main positions in the Clark Field-Fort Stotsenburg sector. The detachment therefore withdrew without making any serious defense of Angeles, which the enemy occupied on 27 January.

The Yanagimoto Detachment had barely moved back into the main positions when the enemy, wheeling west from Highway 3, launched a full-scale attack toward Clark Field and Fort Stotsenburg on 28 January. All available artillery firepower was thrown into an effort to stem this attack. By nightfall, however, the enemy had pressed up close to the first-line defenses of the Eguchi Detachment and was already in possession of part of Clark Field.

Elements of the Eguchi Detachment carried out a strong raiding attack on the enemy right flank during the early morning hours of 29 January but were obliged to withdraw before

[486]

daybreak. The enemy then resumed his assault following a heavy artillery and mortar preparation. Although the tanks of the Yanagimoto Detachment were thrown into a determined counterattack in the late afternoon, this failed to regain any ground, and by the close of the day, a serious breach had been driven through the Japanese first-line positions.55

The enemy was now closing in rapidly on Fort Stotsenburg. Maj. Gen. Tsukada recognized that it would be futile to attempt to restore the shattered forward line and ordered the Eguchi Detachment to pull back to its main positions west and north of the fort. Kembu Group headquarters itself transferred to the rear during the night of 29-30 January. The surviving strength of the front-line forces withdrew to the main positions during the 30th and 31st, fighting stubborn rear-guard actions as they went.

Quick to exploit their advantage, the enemy forces overran Sapangbato and most of Fort Stotsenburg on 30 January and immediately pressed on to attack the Eguchi Detachment's mountain strongpoints to the west. Some of these were lost in the early days of February after heavy fighting. The detachment then pulled back to new positions farther to the rear.

In the Snake Hill North sector, the Takaya Detachment had meanwhile held firm against another prong of the enemy attack from the direction of Mabalacat. Early in February, however, pressure in this sector sharply increased, and on the 9th the detachment was ordered to move back into the rear positions occupied by Rear Adm. Sugimoto's naval troops.56 This permitted the enemy to drive a wedge between the Takayama Detachment on the north flank and the rest of Maj. Gen. Tsukada's forces. After mid-February disintegration became rapid, and the Kembu forces were no longer able to do more than harass the enemy by small-scale raids.57

A startling new development had meanwhile taken place in another part of the Kembu operational zone. Just as the fighting in the Clark Field sector reached its climax on 29 January, General MacArthur landed a fresh invasion force near San Antonio, on the south west coast of Zambales Province. The Nagayoshi Detachment,58 responsible for the defense of Bataan Peninsula, had no forces in the landing area, and the enemy put his troops ashore without opposition. The invading force immediately began advancing along the highway leading southeast to Olongapo, its objective apparently being to cut across the base of Bataan Peninsula and join in a concerted assault on Manila.

[487]

At Olongapo, elements of the Nagayoshi Detachment fought a brief but brisk delaying action as the enemy moved in on 30 January. They then withdrew eastward to the detachment's main positions, which were organized in depth guarding the narrow mountain defile on the highway to Dinalupihan. The enemy advance was temporarily checked when it reached these defenses. Only ,after a sustained assault by forces estimated to total at least one division, supported by heavy fire-bomb attacks from the air, was the detachment forced to yield its forward positions.

The enemy now resorted to an encircling maneuver. Hostile elements swung around to the north of the Nagayoshi Detachment's main positions and attacked from the rear on 7 February. Under the combined weight of the frontal assault and the thrust from the rear, the detachment forces were driven from the last of their positions by 14 February. Col. Nagayoshi ordered the surviving troops to infiltrate southward to the eastern side of Mt. Natib.59

Battle Dispositions in the

Shimbu Sector

As General MacArthur's divisions swept down the central Luzon plain, the forces of the Shimbu Group accelerated preparations for the defense of Manila and the key mountain positions to the east. In the latter part of January, Lt. Gen. Sbquo Yokoyama, Shimbu Group commander, and his staff estimated that the attack on Manila would develop about the middle of February, possibly involving a new enemy landing in Batragas Province to bring the Philippine capital under simultaneous assault from north and south.60

To meet the anticipated threat to Manila, Fourteenth Area Army, in close coordination with Southwest Area Fleet, had effected a sweeping reorganization and redeployment of the Army and Navy ground forces in the Manila area during January. By 31 January, all these forces, regardless of composition or service of origin, had been placed under the unified command of Lt. Gen. Yokoyama.61

In accordance with the Area Army's basic Luzon defense plans of 19-20 December, Lt. Gen. Yokoyama had withdrawn the bulk of the Army troops stationed in Manila and disposed them in the key mountain positions to the east. The Manila Naval Defense Force, in a coordinated move, had also transferred about 3,000 personnel and considerable quan-

[488]

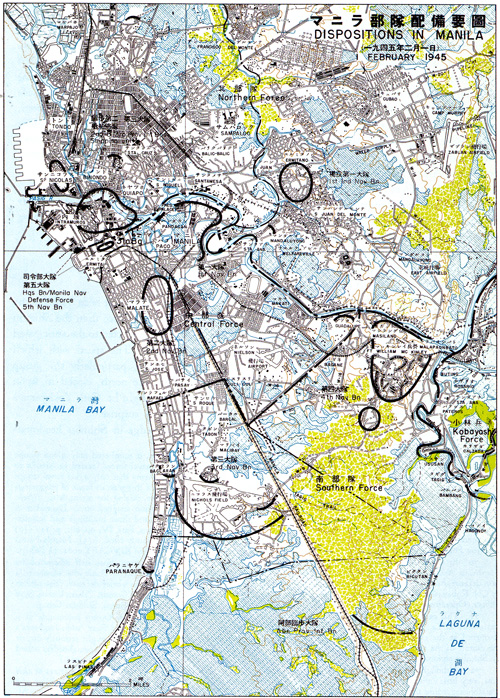

PLATE NO. 117

Dispositions of Shimbu Group, 1 February 1945

[489]

tities of food, ammunition and supplies to the Wawa-Bosoboso sector, east of the capital, but the major portion of its strength, numbering about 13,700, remained deployed in and around the city.

As finally organized to meet the enemy assault, the Shimbu Group zone was divided into two main operational areas. The Manila Naval Defense Force under Rear Adm. Sanji Iwabuchi, 31st Special Base Force commander, was made responsible for the defense of the Manila Bay islands and a mainland area bounded roughly by a line Caloocan-Novaliches-San Mateo-Pasig-Hagonoy-Binan-Tanza. Rear Adm. Iwabuchi's command included the entire naval garrison of Manila, the bay islands, and adjacent areas, as well as all remaining Army forces within the assigned zone.62 The Army forces deployed in and around Manila numbered about 4,000. All Shimbu Group forces outside this zone, with a total strength of about 54,000, were under the direct tactical command of Lt. Gen. Yokoyama. The bulk of these latter forces were disposed in the vital Ipo-Wawa-Antipolo area east of Manila.

By the end of January, Shimbu Group headquarters had almost finished organizing the heterogeneous forces east of Manila into an effective combat task organization. (Plate No. 117) On the north of the line, in the vicinity of Ipo, was the Kawashima Force with an infantry component of four battalions, supported by the main strength of the 8th Field Artillery Regiment and reinforced by a considerable number of air force ground personnel. To the south, guarding the Wawa-Montalban area, was the main strength of the former Manila Defense Force, which had been moved out of the Philippine capital and renamed the Kobayashi Force after its commander, Maj. Gen. Takashi Kobayashi. This force was organized around a nucleus of four infantry battalions.63

The departure of the 105th Division for the nothern redoubt had opened a large gap in the Shimbu Group positions between the left flank of the Kobayashi Force and the north shore of Laguna de Bay. Although Lt. Gen. Yokoyama planned to fill in this weak point with the Noguchi Detachment,64 the end of January found Maj. Gen. Noguchi's troops still engaged

[490]

in the long march from the Bicol Peninsula. As a temporary measure the Okita Detach ment, a five-battalion composite force organized around the 186th Independent Infantry Battalion, and the Kuromiya Detachment, a three-battalion force with the 181st Independent Infantry Battalion as its nucleus, were stationed in the Bosoboso-Antipolo area.65

While Lt. Gen. Yokoyama completed Shimbu Group preparations in the area east of Manila, Rear Adm. Iwabuchi, Manila Naval Defense Force commander, regrouped all the forces comprising the garrison of greater Manila.66 By 1 February, the new organization for combat had been completed.

Three main operational sectors were estab-

[491]

lished for the defense of Manila. The Central Force, under Rear Adm. Iwabuchi's direct com mand, included all of metropolitan Manila south of the Pasig River (excluding Intramuros) and extending inland as far as Guadalupe. (Plate No. 118 ) In this sector were stationed the Headquarters and Headquarters Battalion, Manila Naval Defense Force, and three naval battalions. The Northern Force, under Col. Katsuzo Noguchi, was responsible for Intramuros on the south bank and for all of the city north of the Pasig. At Col. Noguchi's disposal were two provisional infantry battalions, a naval battalion, and a miscellaneous conglomeration of Army shipping units. The Southern Force, under Capt. (Navy) Takesue Furuse, included the Nichols Field and Fort McKinley sectors and all of the Hagonoy Isthmus. Capt. Furuse's command comprised one provisional infantry battalion and two naval battalions.67

The mission which the forces defending Manila were to carry out had meanwhile undergone a fundamental change from that laid down in the Area Army's basic plans of 19-20 December which had envisaged no decisive and prolonged defense of the capital itself by major forces. Preliminary talks to implement these plans took place late in December between representative of the Area Army and Rear Adm. Iwabuchi's command.68 At this time the general policy laid down in the basic plans remained unchanged.

On 6 January, the day following the assignment of the Manila Naval Defense Force to the command of Lt. Gen. Yokoyama, Shimbu Group learned for the first time that, instead of only 4,000 naval troops in Manila, there were actually about 16,700. Pending further

[492]

PLATE NO. 118

Dispositions in Manila, 1 February 1945

[493]

detailed study by the Shimbu Group staff and an exchange of views with regard to the employment of this unexpectedly large number of naval forces, Lt. Gen. Yokoyama on or about 8 January ordered the Manila Naval Defense Force "to continue its present duty, generally with existing dispositions".69

Discussions began immediately thereafter between staff officers of the Shimbu Group and Southwest Area Fleet. These revealed that Southwest Area Fleet desired a firmer defense of Manila than was permitted in the Area Army's basic plans.70 Although the Southwest Area Fleet staff officers had no authority to exercise control of the naval forces with respect to ground operations, the strong views they expressed influenced Lt. Gen. Yokoyama to modify his operational plan so as to provide for a firmer defense in Manila. An order issued to all subordinate commands within the Shimbu Group on 27 January included the following points.71

1. General Operational plan:

The Shimbu Group will concentrate its main strength in the key positions to the east of Manila and assemble maximum supplies in preparation for prolonged and self-sufficient operations. It will exploit the advantages of terrain and strongly fortified positions to crush enemy attacks on these positions and will seize tactical opportunities for carrying out strong raiding counterattacks. It will firmly defend Manila and Ft. McKinley and check their use by the enemy, at the same time destroying the enemy's fighting strength and preparing to counterattack the enemy rear from the main positions when a favorable situa tion arises.

2. Mission of Manila Naval Defense Force:

The Naval Defense Force will defend its already established positions and crush the enemy's fighting strength.

No sooner had this order been issued to the Manila Naval Defense Force than the Shimbu Group found itself subjected to the anticipated two-pronged attack. The speed with which the American forces, particularly the group approaching from the north, closed in upon Manila, however, caught Lt. Gen. Yokoyama's forces completely by surprise.72

The first knowledge in Shimbu headquar-

[494]

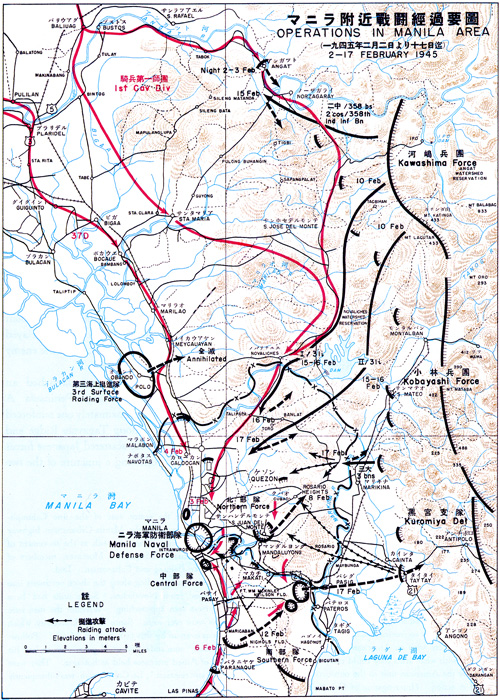

ters of the imminence of the enemy assault was received 1 February. On that date a message from the Uno (Prov.) Infantry Battalion, Kawashima Force, stationed in the Plaridel-Calumpit area, reported that an enemy force, believed to be the advance guard of an estimated one division moving south from the direction of Clark Field, had crossed the Pampanga River near Calumpit.73

While the Uno Battalion, aided by the destruction of virtually the entire network of bridges northwest of Manila, delayed this advance, still another enemy thrust developed from the north. A task force, later identified as the 1st Cavalry Division, had crossed an undestroyed bridge at Cabanatuan, on 1 February. Speeding southward against little opposition, it reached the Angat River the following day.74 After fording the river near Baliuag, this unit split into two columns one of which drove southeast towards Santa Maria while the other followed the Angat River to the east.

The Japanese outpost in Angat fought a delaying action against the latter force during the night of 2-3 February before withdrawing. The second enemy column, however, sped through the hills toward Novaliches and into Manila on the evening of 3 February.75 (Plate No 119 ) Although the Kawashima Force immediately executed small-scale raids against the eastern flank of this column, it was unable to block the route Additional enemy troops and supplies continued to stream into Manila.

The southern prong of the enemy pincer had meanwhile been launched, 31 January, on Batangas Peninsula near Nasugbu. The Japa nese detachment near the beach resisted the enemy landing force only briefly before retiring into the hills. During the initial phases of this invasion, however, special attack craft, operating from the base at Balayan, reportedly sank eight enemy vessels.76

Shortly after the American force moved out from the beachhead en route to Manila, it ran into the main strength of the 3d Battalion, reinf., 31st Infantry, Fuji Force, occupying positions in the narrow mountain defile about fifteen miles inland. This battalion delayed the advance until 3 February, when the enemy broke through the last barrier.

Simultaneously, the enemy launched an airborne invasion of the Batangas Peninsula. A force estimated at approximately one reinforced regiment dropped along Tagaytay Ridge and quickly overcame the scattered Japanese forces in that area. Following a juncture of the two

[495]

PLATE NO. 119

Operations in Manila Area, 2-17 February 1945

[496]

forces. the enemy pushed north rapidly until encountering outposts of the Southern Force, Manila Naval Defense Force, defending river crossings at Las Pinas and Paranaque where the bridges had been destroyed. As the Japanese withdrew towards Laguna de Bay the enemy resumed his advance and began attacking the western flank of the positions south of Nichols Field on 6 February.77

While the Southern Force parried this assault, the Northern Force completed withdrawing the major portion of its strength to the south bank of the Pasig River, leaving in north Manila small rearguard elements in addition to the 3d Surface Raiding Force along the Manila Bay sector78 and the 1st Independent Naval Battalion in the vicinity of San Juan Del Monte. This latter force, under attack from the north since 6 February and threatened from the southwest by another enemy drive along the north bank of the Pasig, was compelled to retreat, 8 February, to Montalban.79

Simultaneously, the Shimbu Group began to formulate plans for a large-scale, coordinated raid against limited objectives occupied by the enemy. It was estimated that only about one American brigade was in northern Manila. Moreover, the successful delaying action being staged at this time by the Nagayoshi Detachment on Bataan and the erroneous belief that the enemy force which had landed at Nasugbu was still being delayed in Batangas by the Fuji Force emboldened the Shimbu staff into taking the offensive.80

Lt. Gen. Yokoyama hoped that such an operation, extending from Ipo Dam south to Antipolo, would not only break the enemy's offensive power by striking the vulnerable east flank before he had time to consolidate his positions but would weld the heterogeneous collection of Japanese personnel into a more effective, confident fighting force for subsequent operations.

In Manila, however, no such optimism prevailed. The Manila Naval Defense Force found itself under heavy attack from both north and south. The situation was rapidly reaching a point where a withdrawal had to be initiated if it was to be even partially successful. Rear Adm. Iwabuchi, with a staff party, therefore withdrew, 9 February, to Ft. McKinley. On that same day, he decided to dispatch one of the staff officers, Lt. Comdr. Koichi Kayashima, to Shimbu Group headquarters to report on the unfavorable situation existing in Manila and to submit a recommendation for withdrawing his forces to the east.

Upon arrival at Shimbu Group headquarters, 10 February, Lt. Comdr. Kayashima found the staff engrossed in the study of the counterattack plans. After he had received Lt. Comdr. Kayashima's report on the Manila situation,

[497]

which, although considerably worse than was known in Shimbu Group headquarters, did not yet appear critical to Lt. Gen. Yokoyama, the Shimbu Group commander directed that the attack plans be enlarged to include provision for the naval forces in Manila to carry out raiding attacks on a large scale in conjunction with the raids from the main positions.81 The general outline of this plan was transmitted, 11 February, by radio to Ft. McKinley and Manila.82

The same day, however, Rear Adm. Iwabuchi had returned to Manila before the message was received from Shimbu Group.83 His party was one of the last to pass from Ft. McKinley to Manila, the enemy effecting a juncture later the same day, 11 February, of the forces attacking from the south and the north in the vicinity of Nielson Field. The 3d Naval Battalion, still defending the Nichols Field area, was now threatened with complete encirclement and therefore withdrew during the night of 12-13 February to the northeast where it joined the naval forces defending Ft. McKinley.

With the enemy vigorously pressing his ground attacks, closely supported by armor and massed artillery fire, it was now apparent in Shimbu Group headquarters that the situation in Manila had reached a critical stage more rapidly than anticipated. Lt. Gen. Yokoyama therefore issued about 13 February an order directing the Manila Naval Defense headquarters to withdraw to Ft. McKinley as the initial step in evacuating the city.

By 15 February, however, when this order was received in Manila,84 strong enemy forces were firmly in control of a three mile wide corrider between Ft. McKinley and the main strength of the naval forces in the city. Rear Adm. Iwabuchi replied on 16 February with the following message:85

Holding the strong point in the city is considered to be of great importance from the viewpoint of the general situation. Withdrawal of the headquarters from Manila would render difficult the execution of operations in Manila. Moreover, we did not succeed in reestablishing overland contact with Ft. McKinley. We are therefore unable to withdraw from Manila.

Lt. Gen. Yokoyama promptly ordered Rear Adm. Iwabuchi to withdraw from Manila on the night of 17-18 February in conjunction with the raiding attacks from the main positions.86

The Shimbu Group had meanwhile completed preparations for the extensive raids. The main attack was to be carried out by two

[498]

battalions of the Kawashima Force attacking Caloocan Airfield and three battalions of the Kobayashi Force attacking Quezon and Banlat Airfield and the vicinity of Rosario. Smaller elements were to cover the extreme north and south flanks of this main attack.87

The 31st Infantry (less 3d Battalion), Kawas hima Force, moved out of its assembly area in the vicinity of Novaliches on the night of 15-16 February.88 The 1st Battalion moved along the highway to a point about three miles south of Novaliches before being halted by an American force. The 31st Infantry (less 1st and 3d Battalions), advancing along the east side of the Novaliches road during hours of darkness, was able to approach within about two miles of Caloocan Airfield before encoun tering enemy positions and retreating.89

In the center, the three provisional battalions of the Kobayashi Force had even less success. This composite force, inadequately prepared for such an attack, launched its assault against the west bank of the Marikina River on 16 February at a point about one mile above Marikina. The Americans had strengthened this line more quickly than had been anticipated, however, and the Japanese were unable to break through the enemy defenses. On the following day, when the attack was resumed, a small bridgehead was established on the west bank of the river. Casualties from enemy artillery proved to be so heavy, however, that the force began to withdraw on 18 February after having previously dispatched a raiding unit of several squads to infiltrate to the objectives.90

The covering forces on the flanks of the main attack registered only small, local gains before withdrawing. On the north, two companies of the 358th Independent Infantry Battalion succeeded in advancing as far as the south side of Angat before being checked by the enemy and forced to withdraw.

During these diversionary raids, only about 1900 troops, representing most of the surviving strength of the 3d and 4th Naval Battalions, withdrew from the Ft. McKinley area on the night of 17 February and entered the main positions of the Shimbu Group near Antipolo.91 About 12,000 men remained in Manila with Rear Adm. Iwabuchi.92 Although repeatedly ordered to evacuate, Rear Adm. Iwabuchi replied that it was now impossible to do so.93

Radio contact with the remnants in Manila

[499]

ceased on 24 February. Shortly thereafter Japanese resistance within the city was completely overcome.

Concurrently with the later phases of the fighting in Manila, the entrance to Manila Bay was brought under attack by the enemy. Following a prolonged sea and air bombardment, the Americans first sent troops ashore on 15 February near Mariveles, on the tip of Bataan Peninsula. Although the Japanese attacked this invasion fleet with about 50 special attack boats, reportedly damaging one cruiser, one destroyer, and two transports, the landing operations continued almost without interruption.94 The small Army detachment defending that area from positions in the mountains northeast of Mariveles was soon forced to withdraw deeper into the mountains.

The garrison on Corregidor, numbering about 4,700, of whom about 800 were Army personnel,95 was meanwhile being subjected to a particularly severe bombardment on the same day. The next day enemy paratroops descended on the western plateau simultaneously with an amphibious landing on the south beach. The enemy was further reinforced by another paratroop unit which dropped later the same day.

During the bitter fighting which followed, the Japanese utilized to a maximum the intricate system of cave and tunnel defenses traversing the island.96 The terrific enemy superiority in tanks and flame throwers, however, finally succeeded in overcoming the last organized resistance on 27 February.

Two days later the American fleet had clear sailing into Manila Bay,97 which by this time was littered with sunken vessels.

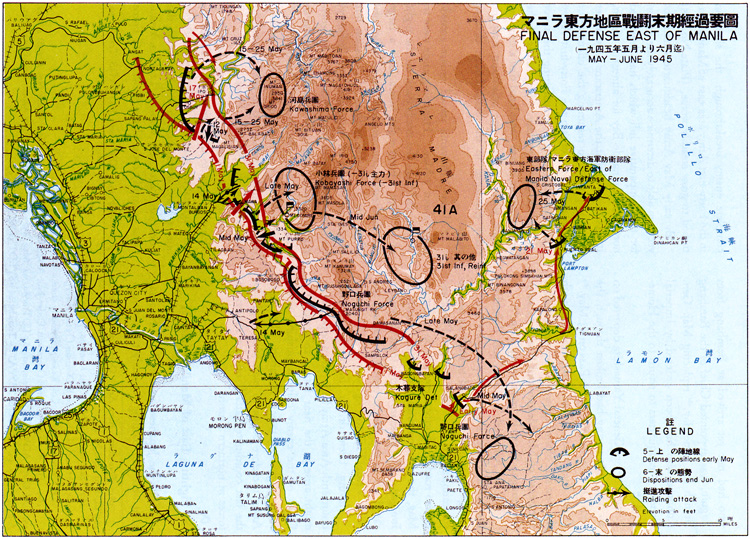

Fighting East of Manila, Phase I

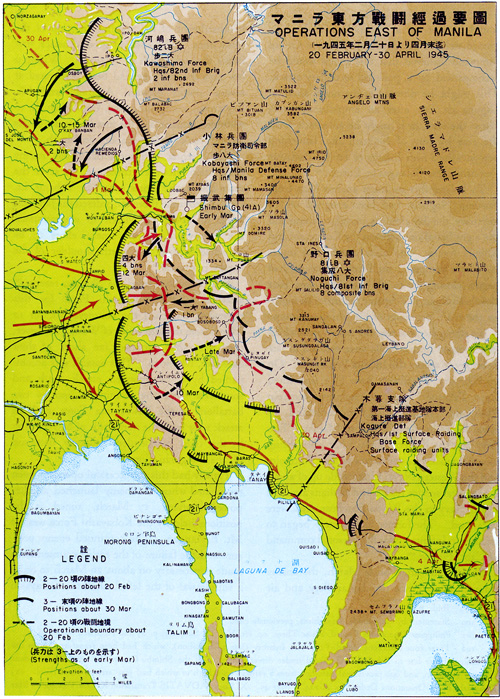

Even before the intense fighting in Manila had begun to subside, the main strength of the Shimbu Group was subjected to increasing enemy pressure all along the line. By late February, most of the forward outposts between Ipo Dam and Antipolo had been driven back upon the main defensive positions.98 (Plate No. 120

Shimbu Group headquarters estimated that this preliminary probing signalled an imminent full-scale attack on the main positions. The northern end of the line, anchored in strong mountain positions near Ipo Dam, and the center, near Wawa and Montalban, were both considered to be strong enough to withstand heavy, prolonged attacks. These positions, furthermore, were well secured on the extreme north flank and in the rear by the trackless Sierra Madre Mountain Range.

The vulnerable southern flank, however, caused Lt. Gen. Yokoyama grave concern. Not only were the natural defenses weak, permitting attack from any of three directions, but the combat effectiveness of the provisional units manning that particular area was considerably below average.

Estimating that the main enemy assault

[500]

PLATE NO. 120

Operations East of Manila, 20 February-30 April 1945

[501]

would be directed at Antipolo and the hills immediately to the north, the Shimbu Group command believed that this attack would be accompanied by a powerful secondary attack. This might be directed at the north shore of Laguna de Bay after an amphibious move across the lake, or it might be an attack from the rear by way of Siniloan after launching new invasions near Infanta or on the Batangas Peninsula near Batangas or Lucena.99

To bolster this southern anchor Maj. Gen. Susumu Noguchi had been assigned on 12 February, the day after his arrival, to command the eight battalions between the Kobayashi and Kogure forces. The units which were under his direct command on Bicol Peninsula had begun closing in to the assembly area near Bosoboso about 18 February to further strength en the main positions of the Shimbu Group.

To strengthen the rear, the naval forces which had escaped from Manila were ordered in late February to secure the Infanta Peninsula. On 27 February, Southwest Area Fleet appointed Capt. Takesue Furuse, commander Northern Philippine Airfield Unit, to command all naval forces in the hills east of Manila. Two days later the Eastern Naval Unit, comprising about 3,000 naval combat troops near Antipolo, and the Western Naval Unit, made up of about 6,000 naval service troops and civilians attached to the Navy in the Wawa-Bosoboso area, were organized. The former immediately began to transfer to Infanta under the personal command of Capt. Furuse.100

Shortly thereafter, on 6 March, the enemy commenced a terrific two-day artillery and air bombardment of the southern portion of the front lines. The ensuing ground attack first broke through south of Antipolo. Within a few days the first line had been penetrated at several points between Antipolo and Mt. Baytangan, compelling Maj. Gen. Noguchi to withdraw remnants of the first line units to the second line of defenses about 10 March.

The deepest and most dangerous enemy penetration, however, threatened to sever the main line in the center near Mt. Yabang. Lt. Gen. Yokoyama, therefore ordered the Japanese forces on about 10 March to counterattack the enemy salient. the main effort to be launched against the north shoulder of the enemy positions.101

Four battalions from the Shimbu reserve,102 attached to the Kobayashi Force for this operation, launched the counterattack on 12 March from the area south of Wawa. However, they were soon stopped far short of their objective, Marikina. This assault was accompanied by a two-pronged attack south and southwest from the vicinity of Ipo by two battalions of the Kawashima Force and an attack west from the north side of Mt. Yabang by the 182d Independent Infantry Battalion of the Noguchi Force.

Hardly had this unsuccessful operation been terminated when the enemy launched another powerful attack, 17 March, aimed at the positions held by the Kobayashi Force west of Mt. Baytangan. The continued enemy pressure and the failure of the earlier counterattack made it necessary on about 20 March to order a withdrawal of the left flank of the Kobayashi

[502]

Force and the Noguchi Force to new positions east of the Bosoboso River.103 This retirement, completed by the end of March, was followed shortly by an enemy drive southeast along the Pililla-Siniloan highway.

Concurrently with this withdrawal, the Western Naval Unit, was ordered to begin moving from the Wawa-Bosoboso area to the Infanta Peninsula.104

In the meantime, a change had been effected in the command status of the Shimbu Group. An Imperial General Headquarters order of 19 March redesignated the group as the Forty-first Army, giving Lt. Gen. Yokoyama for the first time complete command over all subordinate units.105

While the attacks north of Laguna de Bay eased off as the enemy forces regrouped for another attack, powerful enemy drives were launched against the widely scattered forces on the Batangas Peninsula. Here, the Fuji Force, commanded by Col. Masatoshi Fujishige, occupied key positions on the road net and commanding terrain south of Laguna de Bay. The first sustained attack against these positions was launched north and south around the east shore of Lake Taal in mid-March. The Japanese forces in this sector were soon compelled to withdraw east and take up new positions on the north slope of Mt. Malepunyo, five miles northeast of Lipa.106

As the enemy attacks turned eastward towards Lamon Bay and continued into April, Col. Fujishige decided to withdraw still further east and concentrate near the north base of Mt. Banahao, 17 miles northeast of Mt. Malepunyo. Moreover, by this time an enemy column moving along the south shore Laguna de Bay had already reached Pagsanjan, ten miles south of Siniloan completely severing all land com munication with the main positions of the Forty-first Army. Following the assembly near Mt. Banahao during late April, the Fuji Force was incapable of conducting more than small raids.107

In the meantime, the remaining forces on the Bicol Peninsula were also being driven into the hills. An enemy force which landed near Legaspi, 1 April, soon overcame the resistance of the 35th Naval Garrison Unit,108 forcing it about 7 April to withdraw to previously prepared positions about five miles north of Legaspi. Three weeks later the unit was again forced to retreat to the north. Just before reaching Naga, however, the remnants en countered an enemy force moving south and were dispersed in small groups into the nearby mountains. This was the final phase of organ-

[503]

ized resistance on the Bicol Peninsula.109

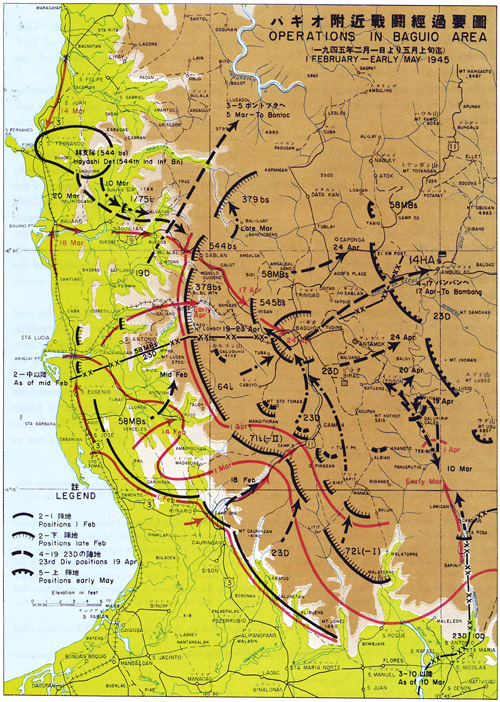

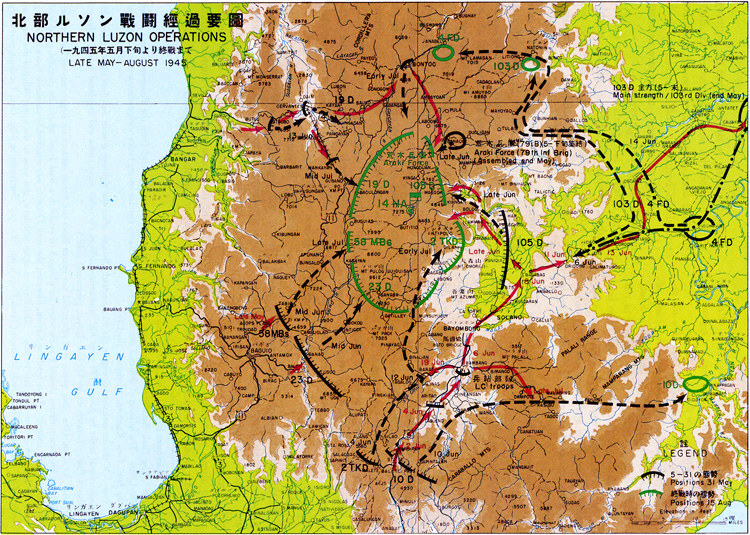

In northern Luzon, meanwhile, Fourteenth Area Army had estimated early in February that a major enemy drive on Baguio was imminent. By this date, moreover, guerrilla bands, operating along the Bagabag-Bontoc-Mankayan road, had already completely ruptured this one remaining vehicular route into the northern redoubt.110 (Plate No. 121)

Although this threat on the north of the Baguio-Mankayan-Bambang triangle required prompt positive action by Fourteenth Area Army, no adequate reserves were immediately available. Only headquarters guards and the 16th Reconnaissance Regiment, 16th Division, consitituted the Area Army reserve.

Reserves were likewise unavailable from other sectors of northern Luzon. Although the enemy had not yet launched an invasion of the Aparri coast, it was estimated that such a move might occur at any time. It therefore appeared inadvisable to weaken this strategically vital sector, in which the 103d Division with three of its independent infantry battalions was deployed.111

Further south, the Cagayan valley defenses were already dangerously undermanned to meet a possible enemy airborne strike. Only one regular infantry battalion (177th Independent Infantry Battalion, 103d Division was available for the defense of the naval air base at Tuguegarao. Elements of the Fourth Air Army had just assembled at Echague.112 On 6 February, Area Army ordered the 4th Air Division to organize eight infantry companies

[504]

PLATE NO. 121

Situation-Northern Luzon, 13 February 1945

[505]

from the remnants of the 2d Parachute Group and miscellaneous flying personnel still remaining at Echague.113 This unit, redesignated the Takachiho Unit114 and placed under command of Col. Kenji Tokunaga, Commander, 2d Parachute Group, was not expected to be ready for combat for at least a month.

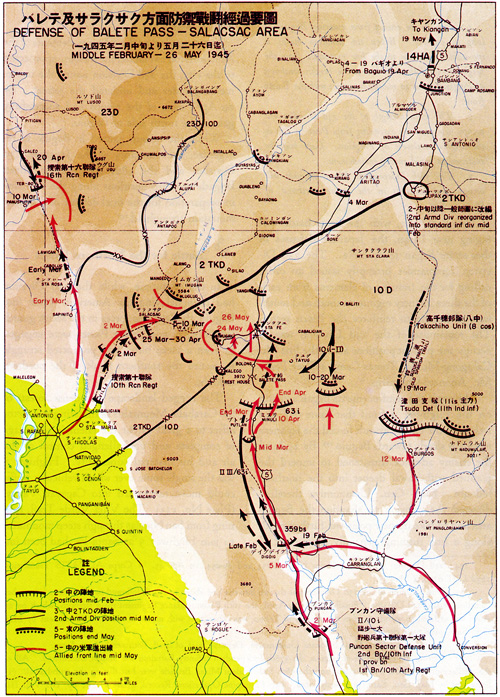

The Bagabag-Salacsac-Balete Pass sector was even more vulnerable. The 10th Division was already committed to the initial defense of the passes. The 105th Division had just begun to displace northward to Bagabag from the vicinity of Puncan and was not expected to complete its movement until early in March. In the meantime, the 10th Infantry (less 2d Battalion), 10th Division, which had arrived at Bagabag on 25 January and been placed under the control of the 105th Division four days later, was busy keeping the guerrillas under control in that vicinity. The survivors of the badly mauled 2d Armored Division were just beginning to assemble near Dupax.

These three divisions had been placed under the tactical control of Maj. Gen. Haruo Konuma, Deputy-Chief of Staff, Fourteenth Area Army, on 23 January, when he had been named chief of the newly organized Bambang Branch, Fourteenth Area Army headquarters.115 Maj. Gen. Konuma, immediately set about the task of organizing provisional infantry battalions from the numerous miscellaneous air force ground personnel and service units. In view of the virtual isolation of the Baguio front, however, these provisional units were to be employed in the 10th Division sector and the Cagayan Valley.

Of almost 9,000 naval personnel in Bayomb ong, the majority were civilian employees of the Navy. One provisional battalion, with a strength of about 500, constituted the only regular combat force early in February.116 Moreover, Southwest Area Fleet headquarters still exercised complete command over the entire group.

On the northwestern coast near Vigan, where the main strength of the Araki Force (79th Infantry Brigade, 103d Division) occupied positions, well organized and active guerrilla operations were believed to presage a secondary enemy landing on the nearby beaches. It was therefore decided not to transfer these Japanese forces to the Bontoc area to join the 357th Independent Infantry Battalion which was heavily engaged with the guerrillas between Sup and Bontoc.

[506]

After careful consideration, it was decided to contract the defense lines guarding Baguio and to transfer the 19th Division to the Bontoc area. The implementing order, substance of which was as follows, was issued on 13 February:117

1. The main strength of the 23d Division will establish strong positions along the perimeter Sablan-Mt. Apni-Mt. Lusen-Camp Three-Malatorre and will carry out fierce raiding tactics to inflict heavy losses on the enemy. Simultaneously preparations will be made to execute a counterattack at any time on the central Luzon plain.

2. The 19th Division, upon being replaced by the 23d Division, will shift to Bontoc and, while occupying as wide an area as possible, prepare to carry out a counterattack against the enemy in the direction of the Cagayan River. The division will also take immediate steps to establish peace and order and secure the main roads within the newly assigned area.

3. The boundary line, which will be the responsibility of the 23d Division, will extend from Mt. Pulog through Mt. Nangaoto and Kibungan to Bacnotan. The time for the change in responsibility will be published in a separate order.118

Another Area Army order of the same day defined the areas of responsibility of the 103d, 105th and 19th Divisions, and placed the 357th Independent Infantry Battalion of the Araki Force under the command of the 19th Division. The following boundaries, to become effective 2400 19 February, were established by this order:119

103d and 19th Divisions:

The line running through Santa Cruz-eastern boundary of Mountain Province-Mt. Camingingel-southern boundary of Abra Province-Hill 305 (four miles east of Santa Maria)-Santa Maria. The boundary will be the responsibility of the 19th Division.

105th and 19th Divisions:

The line running through Mt. Pulog-Hucab-Wacnihan-Santa Cruz. The boundary will be the responsibility of the 19th Division.

As the movement to new positions got under way the following day, the enemy resumed his offensive. (Plate No. 122) Two secondary drives began pressing in the direction of Pugo and along the coastal road toward Aringay, but the major effort was still in the vicinity of Camp One.

Although the last element withdrew in good order from Camp One, 18 February, the 58th Independent Mixed Brigade had borne the brunt of the heavy fighting in the Rosario-Camp One area since late January and the losses, consequently, were exceedingly high. A partial reorganization of the brigade was therefore necessary.120

[507]

Early in March a new enemy drive began to materialize against the weak defenses of the Ambayabang River valley.121 Although this attack, threatening the rear of the Baguio front and the uncompleted Baguio-Aritao road, fell within the boundary of the 2d Armored Division in Salacsac Pass, General Yamashita decided to shift the responsibility to the 23d Division in view of the desperate situation facing the Japanese forces in the Salacsac and Balete Pass area.122 Accordingly, Area Army, on 10 March, shifted the 23d Division left boundary east to include the Ambayabang River, simultaneously assigning to the 23d Division the 16th Reconnaissance Regiment main strength to secure the upper reaches of the river.123

Shortly thereafter, about mid-March, Fourteenth Area Army began to recognize that the fall of Baguio might not be long delayed. Although stubborn defensive fighting forced the enemy to measure his gains in yards, the rate of attrition within the 23d Division was beginning to accelerate rapidly.124 In view of the continuing deterioration, General Yamashita directed the Area Army staff to prepare a plan for prolonging the delaying action deeper in Mountain Province and the Bayombon plain.125

Meanwhile, the Japanese had been trying unsuccessfully since early March to clear the San Fernando area of guerrilla forces pouring in from the north. Concurrently, Maj. Gen. Bunzo Sato, Commander, 58th Independent Mixed Brigade, had been following with considerable concern the progress of the American force advancing north from Aringay. This enemy drive threatened to isolate the Japanese in the San Fernando area. On 10 March, therefore, Maj. Gen. Sato ordered the 1st Battalion, 75th Infantry, to withdraw and take up new positions in the vicinity of Naguilian. Simultaneously, the Hayashi Detachment was ordered to remain in the San Fernando area.126

As the withdrawal began, the Hayashi Detachment pulled in its outpost stationed in the town. The guerrillas quickly followed up this withdrawal to move into San Fernando on 14 March. Six days later, after the American forces had entered Bauang from the south on 18 March, the Hayashi Detachment was ordered to withdraw over secondary roads to Nagui-Nagui thence to take up new positions further to the rear at Sablan.127 The American col-

[508]

PLATE NO. 122

Operations in Baguio Area, 1 February-Early May 1945

[509]

umn, turning east at Bauang, overcame the Japanese defenses at Naguilian after three days of heavy fighting and pushed on late in March to Sablan where the Japanese lines finally held. In the meantime, another enemy assault had penetrated the outer defenses near Galiano, south of Highway 9.

Area Army now feared that the enemy's main effort against Baguio had been shifted from the southwest to the northwest. Long range artillery dropping on Baguio late in March from the northwest supported this contention.128

Preliminary steps to abandon the city were therefore initiated.129 On 10 April, the Inspectorate of Line of Communications was ordered to establish service organizations and disperse supply dumps in the Cervantes-Mt. Pulog-Bayombon-Lubuagan area (22 miles northeast of Bontoc).130

General Yamashita decided, soon thereafter, to transfer his headquarters temporarily to Bambang, pending completion of the command post at Kiangan. Accordingly, the Area Army established on 13 April, the Baguio Branch, Fourteenth Area Army headquarters, to control tactical operations on the Baguio front following the departure of General Yamashita. Maj. Gen. Naokata Utsunomiya, Deputy-Chief of Staff, was simultaneously assigned chief of the branch.131

The defense of Baguio was now entering its final phase. An enemy tank-infantry task force, which had been halted late in March at Sablan, finally broke through the lines, 15 April, after first neutralizing the Japanese artillery emplaced near Monglo. Several tanks swept on through Irisan by the morning of the 17th. Maj. Gen. Sato, rallying every available unit including miscellaneous service elements from Baguio, immediately launched a determined counterattack. As the small enemy force withdrew, the brigade re-established the Japanese line through the northwestern section of Irisan.132

Word now arrived in Baguio that the road to Aritao was completed. General Yamashita, accompanied by a group of staff officers, thereupon departed the evening of the 17th for Bambang. Prior to leaving, the Area Army commander imparted last minute instructions to Maj. Gen. Utsunomiya relative to future steps to be taken by the forces on the Baguio front. The substance of these orders was as follows:133

[510]