CHAPTER XIV

JAPAN'S SURRENDER

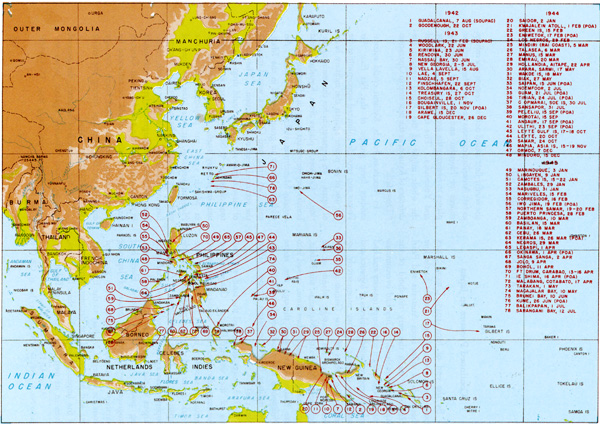

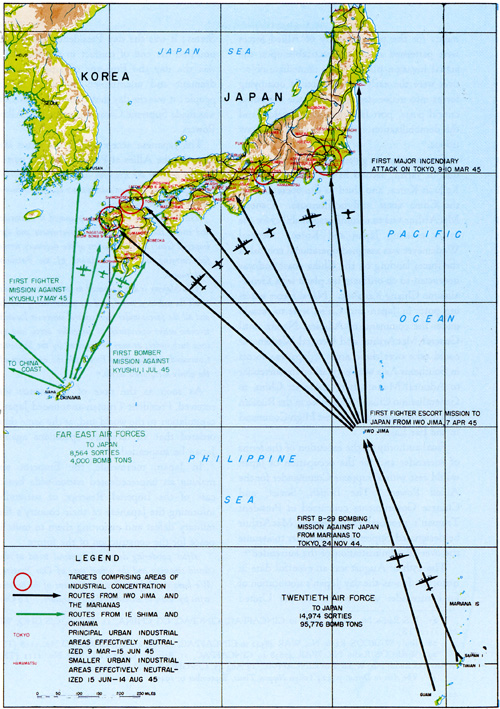

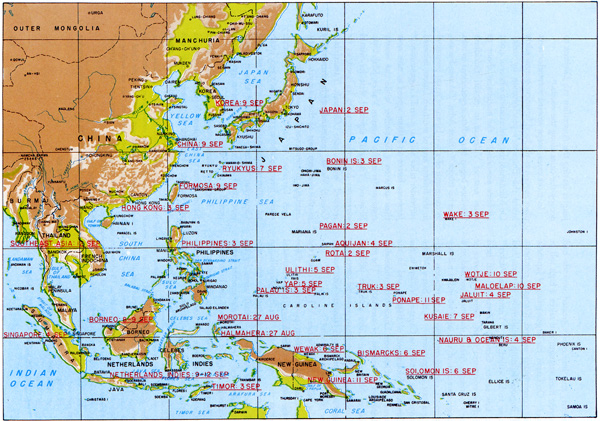

By the end of June 1945, United States forces had advanced their Pacific battle line thousands of miles from Australia and Pearl Harbor to reach the very threshold of the Japanese Homeland. They had overcome an enemy who fought with fierce tenacity and had solved unprecedented problems of logistics and enormous distance as they progressively occupied the coasts of New Guinea and New Britain, secured the strategic islands of the Solomons, Admiralties, Marianas, and Palaus, established airfields on Iwo Jima, moved into the Halmaheras, swept through the entire Philippines, and stood poised on Okinawa, the last military barrier to Japan Proper. (Plate No. 126)

Allied power dominated the land, sky, and sea of the western Pacific. General MacArthur's divisions had retaken vast island territories seized by Japan's armies at the outbreak of war and were now preparing to invade Japan itself. Huge formations of American Superfortresses pounded military and industrial targets on the Japanese mainland with increasing power. The U. S. Pacific Fleet had progressively cleared the ocean of Japanese warships in successive battles which stretched from the waters of Midway to the East China Sea and had bottled the decimated remnants of the Imperial Navy within their base ports. Even in its own Inland Sea and Tokyo Bay, the enemy fleet found neither respite nor refuge as fast American carriers navigated freely off the shores of Honshu and sent their bombing planes to hammer the great anchorages at Kure and Yokosuka. The time was ripe to hurl the whole might of the Allies against the defenses of Kyushu as the first step in Operation "Downfall."

In American hands, Kyushu could accommodate forty groups of the Far East Air Forces and provide unlimited opportunities for the use of air power against the military heart of Japan. In preparation for the main operation, "Coronet," planes from Kyushu could bomb every important target in Honshu, Korea, eastern Manchuria, and northern China. An additional forty air groups based in the Marianas, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa would magnify the potential force of destruction. The planes of these eighty air groups could drop 100,000 tons of bombs in September 1945 and 170,000 tons in January 1946. It was estimated that in March 1946 the projected date of the Honshu invasion, at least 220,000 tons of explosives could be released over the enemy's four main islands. In a single month, therefore, the industrial targets of Japan, contained in about one-tenth the area in which German targets were located, would be saturated by almost one-fourth the total bomb tonnage dropped on the Germans during the entire twelve months of 1944.1

With the approach of summer, the general air and naval offensive against Japan was

[431]

PLATE NO. 126

Allied Landings, August 1942 to August 1945

[432]

intensified to pave the way for the planned invasion of Kyushu. From the middle of May, when fighters based on the island of Ie Shima first attacked targets on southern Japan, the scale of co-ordinated air raids by the Fifth and Seventh Air Forces rose steadily, reaching a peak previously unknown in the Pacific War.2

On Okinawa, all organized Japanese resistance was ended by 21 June, and within two weeks fighters and bombers of the Fifth and Seventh Air Forces began their powerful assaults against Kyushu, neutralizing enemy air strength, severing lines of communication, and isolating the island from the rest of Japan.

Japanese targets in China also received their share of Allied attacks. Shanghai experienced its first large-scale aerial bombardment on 17-18 July, when the Seventh Air Force sent more than 200 Liberators, Mitchells, Invaders, and Thunderbolts from Okinawa over the great enemy-held industrial center in a two-day demonstration of air power. While the Seventh Air Force maintained its raids against Shanghai, the Fifth and Thirteenth Air Forces struck from bases in the Philippines to hit Formosa, Amoy, Swatow, Canton, and Hong Kong. The long-range bombers from the Marianas maintained a continuous shuttle over Japan itself, reducing its great industrial cities to ashes and rubble.3

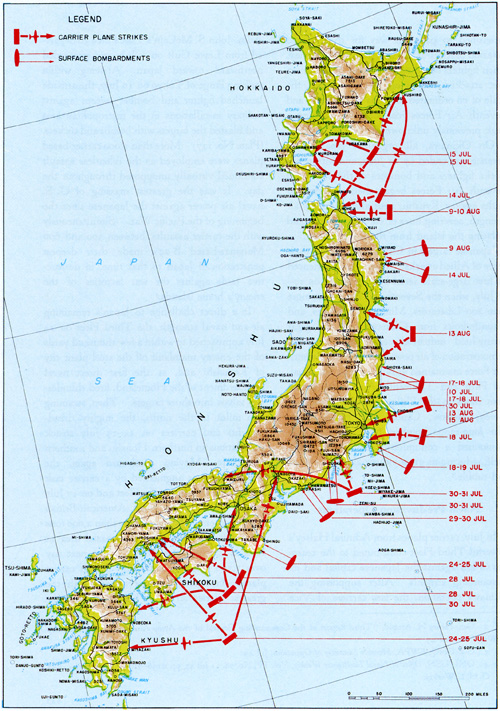

In July, carrier planes from Admiral Halsey's powerful Third Fleet contributed to the cease less strikes against the Japanese capital and its surrounding airfields. After supporting the Okinawa operation, the fast carriers of Vice Adm. John S. McCain's Task Force 38 departed from Leyte Gulf on 1 July and proceeded northward toward Japan. Arriving within striking range of Tokyo on 10 July, the armada launched fighter and bomber sweeps against military installations in the metropolitan area and blasted the targets with bombs and rockets. (Plate No. 127) More than 1,000 carrier-based planes were employed as the relentless assault continued virtually unopposed throughout the day. It was the greatest massing of U.S. naval air power against the Japanese since the beginning of the Pacific War. Simultaneously with the carrier assaults, between 500 and 600 Marianas-based B-29's made their deepest penetration of Japan to that time, in destructive raids against the war factories of the enemy's home islands.4

In a direct challenge to Japan's remaining air and naval strength, the Third Fleet on 14 July approached to within a few thousand yards of the enemy mainland off the steel plant city of Kamaishi and, in the first direct naval bombardment of the Homeland, fired thundering salvos into shore targets. Then, steaming 250 miles to the north, the mighty dreadnoughts and carriers on 14-15 July struck installations in northern Honshu and southern Hokkaido. Moving southward again, the Third Fleet was augmented by a carrier task force of the British Pacific Fleet and on 17 July carried out the first joint American-British bombardment of Japan. More than 2,000 tons of shells were fired into the coastal area at Hitachi, northeast of Tokyo. The next day over 1,500 United States and British carrier planes climaxed the shore attacks with the greatest carrier strike in history against the

[433]

PLATE NO. 127

Third Fleet Pre-Invasion Operations against Japan

[434]

Tokyo area.

Following eight days of continuous assault on enemy airfields, shipping, and industrial targets, the Third Fleet, together with its accompanying British fleet units, turned its attention to eliminating whatever was left of the Japanese Navy. A heavy attack was launched on 18 July, when hundreds of carrier planes concentrated on the enemy warships, including the battleship Nagato, which were anchored at Yokosuka naval base. At the same time, a light detached force of the Third Fleet bombarded military installations at Nojima Saki during the night of 18-19 July.

Five days later, on 24 and 25 July, extensive air raids were launched against Kure and the Inland Sea area by the combined American-British naval force. This sixth carrier strike against the Japanese Homeland since 10 July was followed by another raid on 28 July. Seventh Air Force Liberators from bases on Okinawa joined the attack on Japan's remaining naval units in Empire waters by blasting the anchored warships at Kure. On 30 July, the Tokyo area was again pounded by aircraft from the fast carriers, while battleships poured more than 1,000 tons of shells into the key port, rail center, and industrial city of Hamamatsu on the east coast of central Honshu. Bad weather delayed the naval onslaught for the first few days of August, but on the 9th and 10th, northern Honshu was again subjected to air and sea attacks. The final heavy blow was delivered against Tokyo on 13 August, with carrier planes raking airfields and other military installations as primary targets.5 The suspension of hostilities early on the morning of the 15th found some carrier planes already airborne for an attack on Tokyo, but only one wave hit the objective area; a second wave was recalled before reaching its targets.6

Resistance by the Japanese to this stinging nine-tailed lash of Allied naval and air power was scattered and ineffective; the enemy sought to conserve his few remaining planes and ships for the expected invasion. In Asia, meanwhile, several Japanese ground divisions were being steadily deployed to defend the important industrial regions of northern China after the Soviet Union on 5 April had announced its intention not to renew its existing neutrality treaty with Japan.7

Against the background of final military preparations for the invasion of Japan, international negotiations were under way which were ultimately to make the projected operations "Olympic" and "Coronet" unnecessary. On 17 July 1945, the President of the United States, the Prime Minister of Great Britain, and the Premier of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics met in a series of conferences at Potsdam, Germany, and discussed, among other things, the acceleration of the campaign against Japan. One result of this tripartite conference was that the Soviet Union finally agreed to enter the Pacific war. Another equally outstanding product of the Potsdam conferences was the Potsdam Declaration. President Truman and Prime Minister Atlee, with the concurrence of the President of the National Government of China, issued a final ultimatum

[435]

to the Japanese Government that gave Japan the choice of surrender or destruction. Set forth in powerful words of warning, the Potsdam Declaration read in part:

... The prodigious land, sea and air forces of the United States, the British Empire and of China, many times reinforced by their armies and air fleets from the west, are poised to strike the final blows upon Japan. This military power is sustained and inspired by the determination of all the Allied Nations to prosecute the war against Japan until she ceases to resist.

The result of the futile and senseless German resistance to the might of the aroused free peoples of the world stands forth in awful clarity as an example to the people of Japan. The might that now converges on Japan is immeasurably greater than that which, when applied to the resisting Nazis, necessarily laid waste the lands, the industry and the method of life of the whole German people. The full application of our military powers, backed by our resolve, will mean the inevitable and complete destruction of the Japanese armed forces and just as inevitably the utter destruction of the Japanese homeland.

The time has come for Japan to decide whether she will continue to be controlled by those self-willed militaristic advisers whose unintelligent calculations have brought the Empire of Japan to the threshold of annihilation, or whether she will follow the path of reason ... .

After listing seven terms under which the Allies would accept the Japanese capitulation, the declaration continued:

We call upon the Government of Japan to proclaim now the unconditional surrender of all Japanese armed forces, and to provide proper and adequate assurances of their good faith in such action. The alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction.8

The decision rested with Japan. Would it be "prompt and utter destruction," or surrender according to the plans outlined at Cairo9 and Potsdam, which accorded Japan an opportunity to refit herself for membership in a world of peaceful nations?

In anticipation of Japan's possible surrender, it now became necessary to accelerate the preparation of plans for a peaceful entry into the enemy's homeland. The course of events had given the strategic control of the Pacific War to the United States, and as the conflict progressed it became the nation chiefly responsible for the conduct of all operations dealing with Japan. Although the broad policies of occupation were agreed upon by the major Allied governments in accordance with the United Nations Charter, the United States would execute these policies, provide and regulate the main occupation forces, and designate their commander. Such control also would enable the institution of a strong centralized administration to avoid dividing Japan into national zones of independent responsibility as had been done with Germany.10

In accordance with instructions from the Joint Chiefs of Staff received early in May 1945, General MacArthur had immediately

[436]

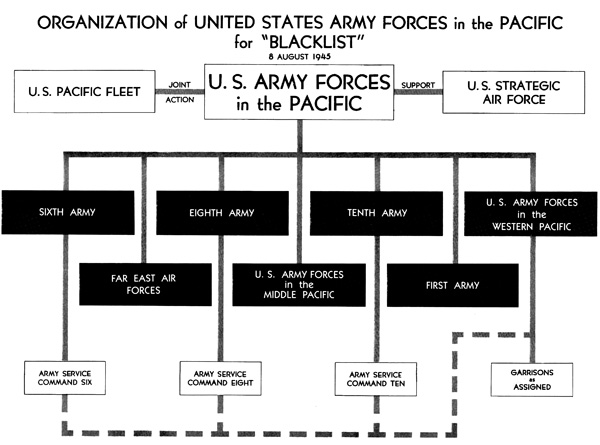

directed his staff to prepare a plan for a possible peaceful occupation. The first edition of this plan, designated "Blacklist," was published on 16 July and presented four days later at Guam for comparison with a concurrent plan for occupation termed "Campus" which was being formulated by Admiral Nimitz.11 General MacArthur's proposals were based on the assumption that it would be his responsibility to impose surrender terms upon all elements of the Japanese military forces within Japan and that he also would be responsible for enforcing the demands of Allied commanders in other areas.

The final edition of "Blacklist" called for the progressive and orderly occupation in strength of an estimated fourteen major areas in Japan and from three to six areas in Korea so that the Allies could exercise unhampered control of the various phases of administration.12 These operations would employ 22 divisions and 2 regimental combat teams, together with air and naval elements, and would utilize all United States forces immediately available in the Pacific. (Plate No. 128) Additional forces from outside the theater would be requisitioned if occupational duties in Formosa or in China were required. "Blacklist" Plan provided for the maximum use of existing Japanese political and administrative organizations since these agencies exerted an effective control over the population and could obviously be employed to good advantage by the Allies. If the functioning governmental machinery were to be completely swept away, the difficulties of orderly direction would be enormously multiplied, demanding the use of greater numbers of occupation forces.13

The preliminary opinions of the Joint Chiefs of Staff regarding the initial phase of the occupation inclined generally toward large-scale independent naval landings as envisioned in the Pacific Fleet Headquarters plan "Campus."14 "Campus," the naval counterpart of "Blacklist," provided for entry into Japan by United States Army forces only after independently operating advance naval units had made an emergency occupation of Tokyo Bay and seized possession of key positions on shore including, if practicable, an operational airfield in the vicinity of each principal anchorage.15

General MacArthur felt that this concept was strategically unwise and dangerous. Although he agreed that, immediately after capitulation, the United States Fleet should move forward, seize control of Japan's Homeland waters, take positions off critical localities, and begin mine sweeping operations, he thought that these steps should introduce immediate landings by strong, co-ordinated ground and air forces of the army, fully prepared to overcome any potential opposition. General MacArthur believed that naval forces were not designed to effect the preliminary occupation of a hostile country whose ground divisions were still intact and contended that the occupation of large land areas involved operations which were fundamentally and basically a mission of the army. The occupation, he maintained, should proceed along sound tactical lines with each

[437]

PLATE NO. 128

"Blacklist" Organization of Forces

[438]

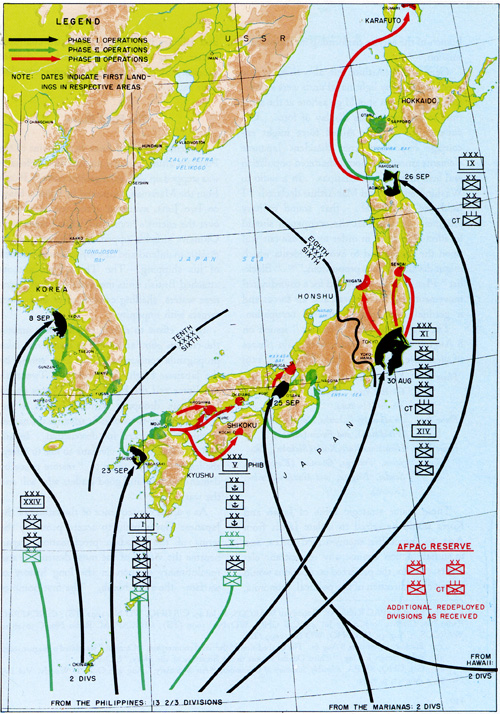

PLATE NO. 129

Basic Plan for the Occupation of Japan

[439]

branch of the service performing its appropriate mission.

General MacArthur felt also that, in the event landings by light naval units were authorized, army troops should go ashore at the same time to implement the display of force. Occupation by a weak Allied force might encourage opposition from dissident Japanese elements among the bomb-shattered population and lead to grave repercussions. In a radio to Washington, General MacArthur declared, "I hold the firm belief ... that sound military judgment dictates that the occupation should be effected in force in order to impose our will upon the enemy and to avoid incidents which might develop serious proportions."16 "Blacklist" Plan therefore provided for a co-ordinated movement of ground, naval, and air forces and a gradual but firmly regulated occupation.

The final edition of " Blacklist " issued on 8 August was divided into three main phases of successive occupation, viz: (Plate No. 129)

Phase I: Kanto Plain, Nagasaki-Sasebo, Kobe-Osaka-Kyoto, Seoul (Korea), and Aomori-Ominato.

Phase II: Shimonoseki-Fukuoka, Nagoya, Sapporo (Hokkaido), and Fusan (Korea).

Phase III: Hiroshima-Kure, Kochi (Shikokku), Okayama, Tsuruga, Otomari (Karafuto), Sendai, Niigata, and Gunzan-Zenshu (Korea).

These major strategic areas of Japan and Korea would be seized to isolate Japan from Asia, to immobilize enemy-armed forces, and to initiate action against any recalcitrant elements. Thus, the projected occupations would permit close direction of the political, economic, and military institutions of the two countries. Other areas would be occupied as deemed necessary by army commanders to accomplish their missions.17

To lend additional force to the terms of the Potsdam ultimatum, the air and naval offensive was stepped up with even greater power. B-29's from the Marianas, supported by fighters based on Iwo Jima, averaged 1,200 sorties a week over the enemy's homeland, while planes from Okinawa airfields ripped his positions on the Asiatic mainland and destroyed what remained of his shipping. The Third Fleet and its attached British units meanwhile roamed Japanese waters, shelling coastal cities and shore targets with impunity.18

In an effort to minimize the losses among the civilian population and to counteract false propaganda concerning Allied aims spread by the Japanese High Command, the Twentieth Air Force and the Far East Air Forces on 28 July began dropping warning leaflets to announce seventy-two hours in advance the names of the cities marked for destruction. In addition to notifying all civilians to flee to safety, the leaflets advised them to "restore peace by demanding new and good leaders who will end the war."19

As a direct consequence of the failure of the Japanese Government to accept promptly the terms of the Potsdam proclamation, Japan became the victim of the most destructive and revolutionary weapon in the long history of warfare-the atom bomb. The first bomb of

[440]

this type ever used against an enemy was released early on 6 August from an American Superfortress over the military base city of Hiroshima and exploded with incomparable and devastating force. The city was almost completely and uniformly leveled.

On 7 August President Truman electrified the world with a broadcast statement which declared:

Sixteen hours ago an American airplane dropped one bomb on Hiroshima, an important Japanese army base. That bomb had more power than 20,000 tons of TNT .... With this bomb we have now added a new and revolutionary increase in destruction to supplement the growing power of our armed forces....

It is an atomic bomb. It is a harnessing of the basic power of the universe ....

We are now prepared to obliterate more rapidly and completely every productive enterprise the Japanese have above ground in any city. We shall destroy their docks, their factories, and their communications. Let there be no mistake; we shall completely destroy Japan's power to make war.

It was to spare the Japanese people from utter destruction that the ultimatum of July 26 was issued at Potsdam.20

With the echo of this cataclysmic explosion reverberating around the world, another staggering blow befell the Japanese. The Soviet Union on 8 August declared war on Japan and hastily sent troops against the Japanese Kwantung Army in Manchuria. The Japanese were now assailed from every side.

On 9 August a second atomic bomb destroyed the city of Nagasaki amid a cloud of dust and debris that rose 50,000 feet and was visible for more than 175 miles.20 The two bombs which fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were dropped by the 509th Composite Bomb Group based on Tinian. The selection of Nagasaki as the second objective of the atomic bomb was caused by unfavorable weather conditions. After circling for fifty minutes above the smoke-obscured city of Kokura, which was the primary target, the bombing plane flew on to drop the bomb over Nagasaki, the alternate target.21

The advent of the atomic bomb coming on the heels of a long series of paralyzing military disasters, hastened the surrender which was already being intensively deliberated by Japan's leaders. By 10 August Japan had had enough; she recognized her situation as hopeless. After much internal struggle and argument, the Japanese Government instructed its Minister to Switzerland to advise the United States through the Swiss Government that the terms of the Potsdam ultimatum would be accepted if Japan's national polity could be preserved. The Japanese note read in part

... the Japanese Government several weeks ago asked the Soviet Government, with which neutral relations then prevailed, to render good offices in restoring peace vis-a-vis the enemy power. Unfortunately, these efforts in the interest of peace having failed, the Japanese Government in conformity with the august wish of His Majesty to restore the general peace and desiring to put an end to the untold sufferings entailed by war as quickly as possible, have decided upon the following:

The Japanese Government are ready to accept the terms enumerated in the joint declaration which was issued at Potsdam on July 26th, 1945, by the heads of the Governments of the United States, Great Britain, and China, and later subscribed by the Soviet Government with the understanding that the said declaration does not comprise any demand which prejudices the prerogatives of His Majesty as a Sovereign Ruler.

The Japanese Government sincerely hope that this understanding is warranted and desire keenly that an explicit indication to that effect will be speedily forthcoming.22

[441]

On 11 August, the United States, acting on behalf of the United Nations, transmitted a reply which stated:

... From the moment of surrender the authority of the Emperor and the Japanese Government to rule the state shall be subject to the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers who will take such steps as he deems proper to effectuate the surrender terms.

The Emperor will be required to authorize and ensure the signature by the Government of Japan and the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters of the surrender terms necessary to carry out the provisions of the Potsdam Declaration, and shall issue his commands to all the Japanese military, naval, and air authorities and to all the forces under their control wherever located to cease active operations and to surrender their arms, and to issue such other orders as the Supreme Commander may require to give effect to the surrender terms.

Immediately upon the surrender, the Japanese Government shall transport prisoners of war and civilian internees to places of safety as directed, where they can quickly be placed aboard Allied transports.

The ultimate form of government of Japan shall, in accordance with the Potsdam Declaration, be established by the freely expressed will of the Japanese people.

The armed forces of the Allied Powers will remain in Japan until the purposes set forth in the Potsdam Declaration are achieved. 23

While the Japanese Government pondered the Allied answer, President Truman, on 12 August, directed the Strategic Air Force to cease its attacks.24 The Far East Air Forces and the Allied Fleet in Japanese waters, however, continued their steady pounding. When no reply was received from the Japanese by 13 August, the Strategic Air Force was ordered to renew its operations25 and on the same day 1,000 carrier planes from the Third Fleet made their final raid on Tokyo.

Never before in history had one nation been the target of such concentrated air power. (Plate No. 130) In the last fifteen days of the war, the Fifth and Seventh Air Forces flew 6,372 sorties against Kyushu alone. Forty-nine per cent of this devastating effort was directed at manufacturing areas and docks. The remaining percentage was divided among enemy shipping, air installations, and lines of communication. Thus, with a deafening crescendo of blasting bombs, the Far East Air Forces culminated their blows against Japan. During the last seven and one-half months of the war their planes had destroyed or badly damaged 2,846,932 tons of shipping and 1,375 enemy aircraft, dropped 100,000 tons of bombs, and flown over 150,000 sorties.26

The end of the war in Europe had not only released additional ground, air, and naval forces for the war against Japan but it had also enabled the Soviet Union to mass its forces for an attack upon Manchuria and northern China. The veteran armies of General MacArthur were poised and ready for an invasion of Kyushu and Honshu. The warning to surrender or be destroyed had not been composed of idle words. Stark and ruinous defeat was already a frightening certainty for the Japanese.

While Japan considered its final acceptance of the Allied terms, preparations for the progressive occupation of its cities and military possessions were already completed. The formal directive for the occupation of Japan, Korea, and the China coast was issued by the Joint Chiefs of Staff on 11 August. Arrange-

[442]

PLATE NO. 130

Aerial Bombardment of Japan

[443]

ments for the peaceful entry of Allied forces were patterned as far as practicable upon the actual invasion plans. The immediate objectives were the early introduction of occupying forces into major strategic areas, the control of critical ports, port facilities, and airfields, and the demobilization and disarmament of enemy troops.27

First priority was given to the prompt occupation of Japan, second to the consolidation of Keijo in Korea, and third to the operations on the China coast and in Formosa. General MacArthur was to assume responsibility for the forces entering Japan and Korea. General Wedemeyer was assigned operational control of the forces landing on the China coast and was instructed to co-ordinate his plans with Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. Naval forces entering ports in Japan and China were to remain under the command of Admiral Nimitz until General MacArthur and General Wedemeyer could take over these areas. Japanese forces in Southeast Asia were earmarked for surrender to Admiral Mountbatten, those in China to Generalissimo Chiang, and those in the Russian area of operations to the Soviet High Command in the Far East.28

Final authority for the execution of the terms of surrender and for the occupation of Japan would rest with a Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers. The British, Soviet, and Chinese Governments concurred in President Truman's proposal that General MacArthur be designated Supreme Commander to assume the over-all administration of the surrender.29

The 15th of August was an eventful date in history. It was the day Japan's notification of final surrender was received in the United States; it was the day President Truman announced the end of conflict in the Pacific; it was the day the Emperor of Japan made a dramatic and unexampled broadcast to his people; it was the day that General MacArthur was made Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers.

The Japanese acceptance of the terms laid down by the Allies at Potsdam read in part:

His Majesty the Emperor has issued an Imperial Rescript regarding Japan's acceptance of the provisions of the Potsdam declaration:

His Majesty the Emperor is prepared to authorize and ensure the signature by his Government and the Imperial General Headquarters of the necessary terms for carrying out the provisions of the Potsdam declaration.

His Majesty is also prepared to issue his commands to all the military, naval, and air authorities of Japan and all the forces under their control wherever located to cease active operations, to surrender arms, and to issue such orders as may be required by the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces for the execution of the above-mentioned terms.30

As soon as the note of acceptance was received, President Truman announced Japan's capitulation to the world and, at the same time, ordered that all offensive operations against Japan be suspended.

In Japan, meanwhile, the Emperor was making an unprecedented nation-wide broadcast of the Imperial Rescript of surrender, informing the Japanese of their country's first military defeat and exhorting them to unite in peace for the construction of the future:

After pondering deeply the general trend of the world situation and the actual state of Our Empire, We have decided to effect a settlement of the present crisis by resort to an extraordinary measure. To Our

[444]

good and loyal subjects, we hereby convey Our will.

We have commanded Our Government to communicate to the Governments of the United States, Great Britain, China and the Soviet Union that Our Empire accepts the terms of their Joint Declaration ... .

Hostilities have now continued for nearly four years. Despite the gallant fighting of the Officers and Men of Our Army and Navy, the diligence and assiduity of Our servants of State, and the devoted service of Our hundred million subjects-despite the best efforts of all-the war has not necessarily developed in our favor, and the general world situation-also is not to Japan's advantage ....

Should we continue to fight, the ultimate result would be not only the obliteration of the race but the extinction of human civilization. Then, how should We be able to save the millions of Our subjects and make atonement to the hallowed spirits of Our Imperial Ancestors? That is why We have commanded the Imperial Government to comply with the terms of the joint Declaration of the Powers....

The suffering and hardship which Our nation yet must undergo will certainly be great. We are keenly aware of the innermost feelings of all ye, Our subjects. However, it is according to the dictates of time and fate that We have resolved, by enduring the unendurable and bearing the unbearable, to pave the way for a grand peace for all generations to come.

Since it has been possible to preserve the structure of the Imperial State, We shall always be with ye, Our good and royal subjects, placing Our trust in your sincerity and integrity. Beware most strictly of any outburst of emotion which may engender needless complications, and refrain from fraternal contention and strife which may create confusion, lead ye astray and cause ye to lose the confidence of the world. Let the nation continue as one family from generation to generation with unwavering faith in the imperish ability of our divine land and ever mindful of its heavy burden of responsibility and the long road ahead. Turn your full strength to the task of building a new future. Cultivate the ways of rectitude, foster nobility of spirit, and work with resolution so that ye may enhance the innate glory of the Imperial State and keep pace with the progress of the world. We charge ye, Our loyal subjects, to carry out faithfully Our will.31

To initiate the steps towards the implementation of the surrender terms, President Truman announced the appointment of General MacArthur as the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers and dispatched the following orders to the Japanese Government:

You are to proceed as follows:

Direct prompt cessation of hostilities by Japanese forces, informing the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers of the effective date and hour of such cessation.

Send emissaries at once to the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers with information of the disposition of the Japanese forces and commanders, and fully empowered to make any arrangements directed by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers to enable him and his accompaying forces to arrive at the place designated by him to receive the formal surrender.

For the purpose of receiving such surrender and carrying it into effect, General of the Army Douglas MacArthur has been designated as Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, and he will notify the Japanese Government of the time, place, and other details of the formal surrender.32

From the War Department in Washington, the Army Chief of Staff dispatched a message to General MacArthur which read, "Your directive as Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers is effective with the receipt of this message."33

General MacArthur received the announce-

[445]

ment of Japan's capitulation with an expression of deep gratitude:

I thank a merciful God that this mighty struggle is about to end. I shall at once take steps to stop hostilities and further bloodshed. The magnificent men and women who have fought so nobly to victory can now return to their homes in due course and resume their civil pursuits. They have been good soldiers in war. May they be equally good citizens in peace.34

The air waves crackled with urgent radio messages between Manila Headquarters and Tokyo. General MacArthur notified the Emperor and the Japanese Government on 15 August that he had been designated Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers and was authorized to arrange for the cessation of hostilities at the earliest practicable date.35 Accordingly, he directed that the Japanese forces terminate hostilities immediately and that he be notified at once of the effective date and hour of such termination. He further directed that Japan send to Manila on 17 August "a competent representative empowered to receive in the name of the Emperor of Japan, the Japanese Imperial Government, and the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters certain requirements for carrying into effect the terms of surrender."

General MacArthur's stipulations to the Japanese Government included specific instructions regarding the journey of the Japanese representatives to Manila. The emissaries were to leave Sata Misaki, on the southern tip of Kyushu, on the morning of 17 August. They were instructed to travel in a Douglas DC-3-type transport plane, painted white and marked with green crosses on the wings and fuselage, and to fly under Allied escort to an airdrome on Ie Shima in the Ryukus. From there the Japanese would be transported to Manila in a United States plane. The code designation chosen for communication between the Japanese plane and United States forces was the symbolic word " Bataan."37

On the evening of the 16th, General MacArthur was notified that the Emperor of Japan had issued an order at 1600 that day commanding the entire armed forces of his nation to halt their fighting immediately.38 The wide dispersion and the disrupted communications of the Japanese forces, however, made the rapid and complete implementation of such an order exceedingly difficult. As the Japanese apologetically explained, the Imperial order would take approximately two to twelve days to reach Japanese forces throughout the Pacific and Asiatic areas, "but whether and when the order will be received by the first line it is difficult to foresee."39 The radio also stated that members of the Imperial family were being sent to Japan's numerous theaters of operations as personal representatives of the Emperor to expedite and insure full compliance with the Imperial order to cease hostilities.

The departure of the delegates for the Manila negotiations, the Japanese continued, would be slightly delayed "as it is impossible for us to arrange for the flight of our representatives on 17 August due to the scarcity of time allowed us."40 The radio added, however, that preparations were being made with all possible speed and that General MacArthur

[446]

would be immediately informed of the re-scheduled flight date.41 A second message from the Japanese Government on the 16th described the tentative itineraries of the Imperial emissaries who were being dispatched by air to the various fronts.42

General MacArthur's Headquarters assured the Japanese that their intended measures were satisfactory and promised that every precaution would be taken to ensure the safety of the Emperor's representatives on their missions. Further instructions were issued regarding the type of plane to be used in sending the Japanese to Manila, but authorization was given to change the type of plane if necessary.43

Another communication from the Japanese on the 16th asked for clarification of the phrase, "certain requirements for carrying into effect the terms of surrender."44 General MacArthur replied that the signing of the surrender terms would not be among the tasks of the Japanese representatives despatched to Manila.45

On 16 August, Japan's leaders announced that their delegates had been selected and would leave Tokyo for Manila on 19 August.46 It was now only a matter of days before the long-awaited moment of final surrender would become a reality.

Headed by Lt. Gen. Torashiro Kawabe, Vice-Chief of the Army General Staff, the sixteen-man Japanese delegation47 on the morn-

[447]

ing of 19 August boarded two white, green-crossed, disarmed Navy medium bombers and departed secretly from Kisarazu Airdrome, on the eastern shore of Tokyo Bay.48 After landing at Ie Shima, according to General MacArthur's instructions, the Japanese passengers were immediately transferred to a U. S. Army transport plane and put down on Nichols Field south of Manila at about 1800 that same day.

On hand to meet the Japanese envoys as they emerged from the plane was a party of linguist officers headed by General Willoughby, General MacArthur's wartime director of intelligence. Following the necessary introductions and identifications, the Japanese were taken immediately to temporary quarters on Manila's Dewey Boulevard to await the meetings scheduled for that evening.49

Less than three hours after their arrival, the sixteen-man Japanese delegation was led by General Willoughby to the first of two conferences held that night with members of General MacArthur's staff. General MacArthur him self was not present. As the solemn procession moved from Dewey Boulevard through the battered and war-torn streets of Manila and up the broad steps of the City Hall, the stony-faced Japanese officers in their beribboned gray-green uniforms, with their peculiarly peaked caps, and with their two-handed Samurai swords dangling from their waists almost to the ground, made a grim and curious picture. Shortly after 2100, the Japanese and American representatives entered General Chamberlin's office and sat down facing each other across the long, black table of the map-covered conference room.50

The meetings continued through the night of the 19th and into the next day.51 As General Sutherland led the discussions, linguists busily scanned, translated, and photostated the various reports, maps, and charts which the Japanese had brought with them. Allied Translator and Interpreter Section personnel worked throughout the night to put General MacArthur's requirements into accurate Japanese before morning. It was a matter of vital importance that all documents be capably and correctly translated so that arrangements for surrender could be completed with a minimum of misunderstanding and a maximum of speed.

The conference proceeded smoothly and all

[448]

major problems were resolved satisfactorily. Results of the negotiations made it advisable to modify some of the original concepts on the problem of occupation. Based upon the full co-operation of the Japanese Government and Imperial General Headquarters, the new modifications provided for gradual occupation of designated areas after the Japanese had disarmed the local troops. No direct demilitarization was to be carried out by Allied personnel; the Japanese were to control the disarmament and demobilization of their own armed forces under Allied supervision.52

General Kawabe expressed his belief that the Japanese would faithfully carry out all Allied demands, but because of the unpredictable reactions of the Japanese civilian and army elements he requested that Japan be given an additional period of preparation before the actual steps of occupation were taken. General Sutherland allowed three extra days. The target date for the initial landings was postponed from 25 August to 28 August. The arrival of the advance unit at Atsugi Airfield was scheduled for 26 August.

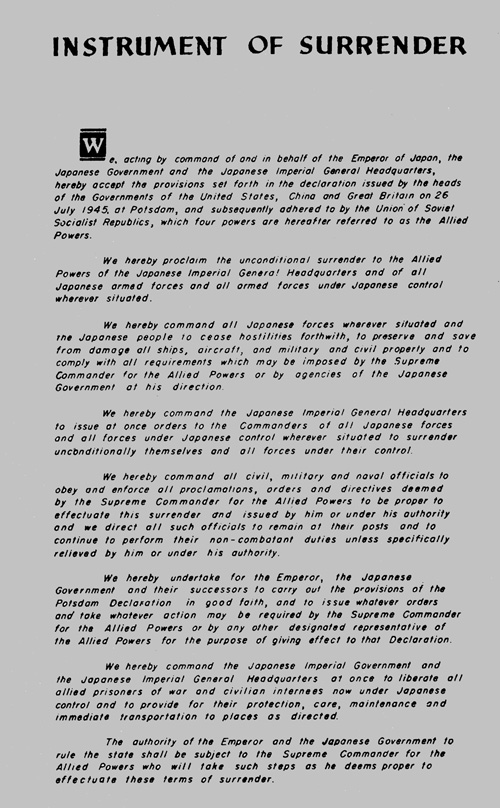

At the close of the conference, General Kawabe was handed the documents containing the "Requirements of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers."53 These directives stipulated General MacArthur's requirements concerning the arrival of the first echelons of the Allied forces, the formal surrender ceremony, and the subsequent reception of the occupation forces. Also given to General Kawabe were a draft of the Imperial Proclamation by which the Emperor would accept the terms of the Potsdam Declaration and command his subjects to cease hostilities, a copy of General Order No. 1 by which Imperial General Headquarters would direct all military and naval commanders to lay down their arms and surrender their units to designated Allied commanders, and lastly the Instrument of Surrender itself which would later be signed on board an American battleship in Tokyo Bay.

The Manila Conference was over. The Japanese delegation left at 1300 on 20 August and started back to Japan along the same route by which it had come. The homeward trip, however, was marred by an accident which caused a few anxious moments to the bearers of the surrender documents. The plane carrying the key emissaries had to make a forced landing on a beach near Hamamatsu, and it was not until seven hours after their scheduled time of return that the members of the mission were able to report the results of the Manila Conference to their waiting Premier.54 It now remained for Japan to prepare itself to carry out

[449]

the provisions of surrender and to accept a peaceful military occupation of the Homeland by Allied forces.

General MacArthur anticipated that, subject to weather conditions which would permit the necessary air and naval operations, the Instrument of Surrender would be signed within ten days. "It is my earnest hope," he announced after the departure of Japan's representatives from Manila, "that pending the formal accomplishment of the Instrument of Surrender, armistice conditions may prevail on every front and that bloodless surrender may be effectuated."55

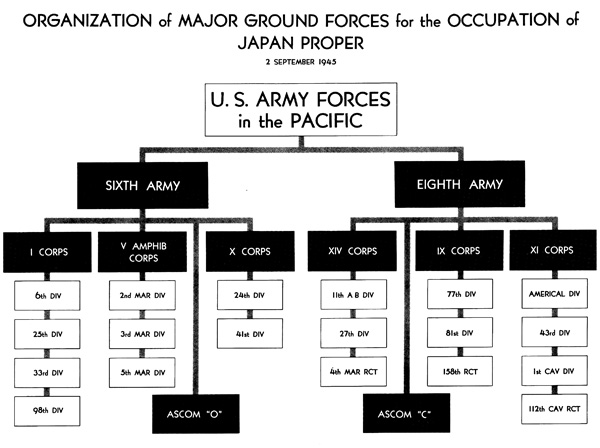

Simultaneously with President Truman's announcement of Japan's acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration, a thorough reorganization of AFPAC forces was effected in preparation for the forthcoming Allied mission in Japan. On 15 August, General MacArthur ordered sweeping changes to strengthen Sixth and Eighth Armies and XXIV Corps (then with Tenth Army in the Ryukyus) for their imminent duties of occupation. (Plate No. 131)

The 11th Airborne Division had moved 800 miles by air with full combat equipment from Luzon to Okinawa in a record time of forty-four hours and had already passed to the control of General Eichelberger's Eighth Army. Eighth Army, which would institute the occupation unassisted until 22 September, was also given control of XI Corps with the Americal, 1st Cavalry, and 43rd Divisions and the 112th Regimental Combat Team, IX Corps with the 77th and 81st Divisions and the 158th Regimental Combat Team, and the 27th Division on Okinawa. In addition Eighth Army included XIV Corps, the 31st Division and the 368th Regimental Combat Team, taken from X Corps, and the 40th Division, taken from Sixth Army.56

General Krueger's Sixth Army was mean while increased by the addition of V Amphibious Corps, with its 2nd, 3rd, and 5th Marine Divisions located in Saipan, Oahu, Guam, and Hawaii. General Krueger also assumed command of X Corps, with the 24th and 41st Divisions; the 6th Division from Eighth Army, and the 98th Division from AFMIDPAC were also transferred to Sixth Army.

XXIV Corps on Okinawa passed from Tenth Army to the direct control of AFPAC to operate independently as the occupation force in Korea, south of the 38 degree parallel. General MacArthur assigned the responsibility for the security of the Ryukyus to Army Service Command I (ASCOM-I) and directed AFWESPAC to assume combat responsibilities in the Southwest Pacific Area. Lt. Gen. Wilhelm D. Styer, Commanding General of AFWESPAC, established two commands to maintain security in the Philippines: the Luzon Area Command and the Southern Islands Area command.57 The former SWPA commands, Allied Land Forces, Allied Naval Forces, and Allied Air Forces, were to be abolished with the signing of the surrender terms, at which time control of the southern portion of the Southwest Pacific Area would pass to the British.58

As the day of formal surrender drew near, all available troop transports of the Far East

[450]

PLATE NO. 131

Organization of Major Ground Forces for the Occupation of Japan Proper

[451]

Air Forces and dozens of the huge Skytrains and Skymasters of the Pacific Air Transport Command were massed at Okinawa to airlift the first occupation forces to Japan in the greatest aerial movement of the Pacific War. On 26 August, General Eichelberger transferred the Eighth Army Command Post from the eastern coastal plain of Leyte to Okinawa and prepared to lead the vanguard forces of the 11th Airborne and 27th Infantry Divisions onto Japanese soil. At this critical juncture, however, a typhoon raging through the Japanese Home Islands caused a delay in Japan's final preparations to receive the occupation forces and resulted in a two-day postponement of the preliminary landings, originally scheduled for 26 August.

The first American landings in Japan were made at 0900 on 28 August by a small airborne advance party of 150 communications experts and engineers. Deplaning at the large navy airfield at Atsugi, some twenty miles southwest of Tokyo, the daring little group fell immediately to the task of setting up the communications and other operational facilities for the swarms of four-engined planes that would bring the 11th Airborne Division to establish the American airhead in the Atsugi area. This advance group was followed three hours later by thirty-eight troop transports carrying protective combat forces and necessary supplies of gasoline, oil, and other equipment.59

The main phase of the airborne operation began at dawn on 30 August. The first plane, bearing a regular forty-man load, touched the runway at 0600. Practically every three minutes thereafter throughout the day, American planes landed on the huge Japanese airfield, gliding down with clockwork precision and without a single mishap. By evening, 4,200 combat-equipped troops of the 11th Airborne were on the ground and strategically deployed to protect the airhead against any eventuality.60

It was a great, though calculated, military gamble. The American elements, outnumbered by thousands to one, were landing in a hostile country where huge numbers of enemy soldiers still had access to their arms. The occupation plan was predicated upon the ability of the Emperor to maintain psychological control over his people and to quell any recalcitrant elements. It was doubtful that the majority of the Japanese people would disobey the Imperial command to surrender peaceably, but the possibility that certain dissident extremists would forcibly oppose the occupation despite all orders had to be carefully considered.61

In view of the unpredictable reactions of the Japanese troops, General Eichelberger flew in to Atsugi early the first day to take personal command of the situation and to make preparations for the arrival of the Supreme Com-

[452]

mander. Fortunately, all apprehensions proved groundless. There was no trouble; not a sign of resistance was apparent. The Japanese had stationed picked and trusted troops around the field and along the main roads of egress to provide security for the greatly outnumbered American soldiers.62 General MacArthur's calculated risk had been well taken.

Shortly after 1400 a famous C-54-the name "Bataan" in large letters on its nose-circled the field and glided in for a landing. From it stepped General MacArthur, accompanied by General Sutherland and his other staff officers. The Supreme Commander's first words to General Eichelberger and the men of Eighth Army and the 11th Airborne Division who greeted him were:

From Melbourne to Tokyo is a long road. It has been a long and hard road, but this looks like the payoff. The surrender plans are going splendidly and completely according to previous arrangements. In all outlying areas, fighting has practically ceased.

In this area a week ago, there were 300,000 troops which have been disarmed and demobilized. The Japanese seem to be acting in complete good faith. There is every hope of the success of the capitulation without undue friction and without unnecessary bloodshed.

The entire operation proceeded smoothly. General MacArthur paused momentarily to inspect the airfield, then stepped into a waiting automobile for the drive to Yokohama. Thousands of Japanese troops were posted along the fifteen miles of road from Atsugi to Yokohama, to guard the route of the Allied motor cavalcade as it proceeded to the temporary SCAP Head-quarters in Japan's great seaport city.63

Meanwhile, Admiral Halsey's Third Fleet, including the British warships, steamed into Japan's coastal waters and anchored in Sagami Bay on the 27th. Japanese naval officers met the incoming fleet units to receive instructions for the safe entry of the Allied Fleet into Tokyo Bay in accordance with General MacArthur's surrender directives. On 29 August, the Third Fleet moved forward into Tokyo Bay to prepare for the landings at Yokosuka.

As the 11th Airborne poured into Atsugi Airfield, troops of the 4th Marine Regimental Combat Team, 6th Marine Division, went ashore at Yokosuka Naval Base on the west bank of Tokyo Bay below Yokohama. Immediately after the airborne landing, elements of the 188th Parachute Glider Regiment sped to Yokohama to take control of the huge dock area. Other patrols of the airborne unit fanned out to the south, and contacted troops of the 4th Marines, whose landing was also completed without incident. The Marine Regiment passed to the control of the Commanding General, Eighth Army immediately after it disembarked.64

The intensive preparation and excitement that attended these first landings on the Japanese mainland did not interfere with the mission of affording relief and rescue to the unfortunate Allied personnel already inside Japan as internees or prisoners. Despite the bad weather that delayed the occupation operation, units of the Far East Air Forces and planes from the Third Fleet continued their surveillance missions. On 25 August they began dropping relief supplies of food, medicine, and clothing to Allied soldiers and civilians in prisoner-of-war and internment camps throughout the main islands.

While the advance echelon of the occupation forces was still on Okinawa, "mercy teams" were organized to accompany the first elements of Eighth Army Headquarters. Immediately

[453]

after the initial landings, these teams established contact with the Swiss and Swedish Legations, the International Red Cross, the United States Navy, and the Japanese Liaison Office and rushed to expedite the release and evacuation, where necessary, of the thousands of Allied internees.65

By 31 August the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment had joined the 188th Paragliders in the Yokohama area and established contact with the 4th Marines at Yokosuka. The 187th Parachute Infantry Regiment had consolidated the Atsugi airhead to secure it as a base for subsequent air activities by the Far East Air Forces and to protect the incoming 27th Infantry Division, also to be airborne from Okinawa.66

The Reconnaissance Troop of the 11th Airborne Division made a subsidiary airlift operation on 1 September, flying from Atsugi to Kisarazu Airfield. This airfield was occupied without incident. On the morning of 2 September, the 1st Cavalry Division began landing at Yokohama as the surrender ceremonies took place in Tokyo Bay. With the exception of Tokyo itself, most of the strategic areas along the shores of Tokyo Bay had by then been secured by Allied forces.67

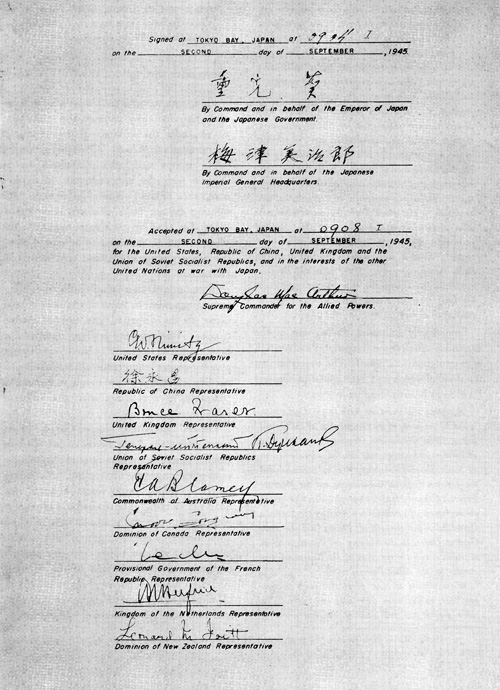

Japan's formal capitulation to the Allies climaxed a week of historic events as the initial steps of the occupation program went into effect. The surrender ceremony took place aboard the Third Fleet flagship, U. S. S. Missouri, on the misty morning of Sunday, 2 September 1945. As the Missouri lay majestically at anchor in the calm waters of Tokyo Bay, convoys of large and small vessels formed a tight cordon around the surrender ship, while army and navy planes maintained a protective vigil overhead. This was the objective toward which the Allies had long been striving-the unconditional surrender of the previously undefeated military forces of Japan and the final end to conflict in World War II.

The decks of the Missouri that morning were crowded with the representatives of the various United Nations that had participated in the Pacific War. Outstanding among the Americans flanking General MacArthur were Admirals Nimitz and Halsey, and General Wainwright who had recently been released from a Manchurian internment camp, flown to Manila, and then brought aboard to witness the occasion. Present also were the veteran staff members who had fought with General MacArthur since the early dark days of Melbourne and Port Moresby.

Shortly before 0900 Tokyo time, a launch from the mainland pulled alongside the great United States warship and the emissaries of defeated Japan climbed silently and glumly aboard. The Japanese delegation included two representatives empowered to sign the Instrument of Surrender, Mamoru Shigemitsu, Minister of Foreign Affairs and Gen. Yoshijiro Umezu of the Imperial General Staff, in addition to three representatives from the Foreign Office, three representatives from the Army, and three representatives from the Navy.68

As Supreme Commander for the Allied

[454]

Powers, General MacArthur presided over the epoch-making ceremony, and with the following words he inaugurated the proceedings which would ring down the curtain of war in the Pacific:

We are gathered here, representatives of the major warring powers, to conclude a solemn agreement whereby peace may be restored. The issues, involving divergent ideals and ideologies, have been determined on the battlefields of the world and hence are not for our discussion or debate. Nor is it for us here to meet, representing as we do a majority of the people of the earth, in a spirit of distrust, malice or hatred. But rather it is for us, both victors and vanquished, to rise to that higher dignity which alone befits the sacred purposes we are about to serve, committing all our peoples unreservedly to faithful compliance with the understandings they are here formally to assume.

It is my earnest hope, and indeed the hope of all mankind, that from this solemn occasion a better world shall emerge out of the blood and carnage of the past-a world dedicated to the dignity of man and the fulfillment of his most cherished wish for freedom, tolerance and justice.

The terms and conditions upon which surrender of the Japanese Imperial Forces is here to be given and accepted are contained in the instrument of surrender now before you ....69

The Supreme Commander then invited the two Japanese plenipotentiaries to sign the duplicate surrender documents: Foreign Minister Shigemitsu, on behalf of the Emperor and the Japanese Government, and General Umezu, for the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters. He then called forward two famous former prisoners of the Japanese to stand behind him while he himself affixed his signature to the formal acceptance of the surrender: Gen. Jonathan M. Wainwright, hero of Bataan and Corregidor and Lt. Gen. Sir Arthur E. Percival, who had been forced to yield the British stronghold at Singapore.

General MacArthur was followed in turn by Admiral Nimitz, who signed on behalf of the United States, and by the representatives of the other United Nations present: Gen. Hsu Yung-Chang for China, Adm. Sir Bruce Fraser for the United Kingdom, Lt. Gen. Kuzma N. Derevyanko for the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, Gen. Sir Thomas A. Blarney for Australia, Col. L. Moore-Cosgrave for Canada, Gen. Jacques P. LeClerc for France, Adm. Conrad E. L. Helfrich for the Netherlands, and Air Vice-Marshall Leonard M. Isitt for New Zealand.

The Instrument of Surrender was completely signed within twenty minutes. (Plate No. 132) The first signature of the Japanese delegation was affixed at 0904; General MacArthur wrote his name at 0910; and the last of the Allied representatives signed at 0920. The Japanese envoys then received their copy of the surrender document, bowed stiffly and departed for Tokyo. Simultaneously, hundreds of army and navy planes roared low over the Missouri in one last display of massed air might.

In signing the Instrument of Surrender, the Japanese bound themselves to accept the provisions of the Potsdam Declaration, to surrender unconditionally their armed forces wherever located, to liberate all internees and prisoners of war, and to carry out all orders issued by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers to effectuate the terms of surrender.

On that same eventful day, the Supreme Commander broadcast a report to the people of the United States. Having been associated with Pacific events since the Russo-Japanese war, General MacArthur was able to speak with the authority of long experience to forecast a future for Japan:

We stand in Tokyo today reminiscent of our

[455]

PLATE NO. 132

[456]

Surrender Document

[457]

countryman, Commodore Perry, ninety-two years ago. His purpose was to bring to Japan an era of enlightenment and progress by lifting the veil of isolation to the friendship, trade and commerce of the world. But, alas, the knowledge thereby gained of Western science was forged into an instrument of oppression and human enslavement. Freedom of expression, freedom of action, even freedom of thought were denied through supervision of liberal education, through appeal to superstition and through the application of force. We are committed by the Potsdam Declaration of Principles to see that the Japanese people are liberated from this condition of slavery. It is my purpose to implement this commitment just as rapidly as the armed forces are demobilized and other essential steps taken to neutralize the war potential. The energy of the Japanese race, if properly directed, will enable expansion vertically rather than horizontally. If the talents of the race are turned into constructive channels, the country can lift itself from its present deplorable state into a position of dignity....70

Immediately following the signing of the surrender articles, the Imperial Proclamation of capitulation was issued. The Proclamation, the draft of which had been given to General Kawabe at Manila, read as follows:

Accepting the terms set forth in the Declaration issued by the heads of the Governments of the United States, Great Britain and China On July 26th 1945 at Potsdam and subsequently adhered to by the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, We have commanded the Japanese Imperial Government and the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters to sign on Our behalf the instrument of surrender presented by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers and to issue General Orders to the Military and Naval forces in accordance with the direction of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers.

We command all Our people forthwith to cease hostilities, to lay down their arms and faithfully to carry out all the provisions of the Instrument of Surrender and the General Orders issued by the Japanese Imperial Government and the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters hereunder.71

Surrender throughout the SWPA Areas

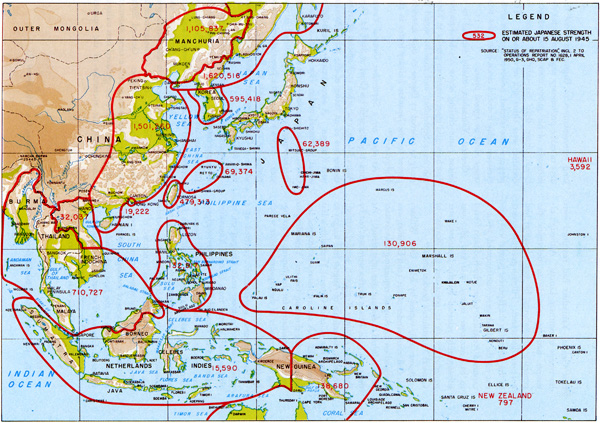

In accordance with the Emperor's proclamation, Japanese army commanders took steps to surrender the millions of their forces in overseas areas. (Chart) Offensive action by U. S. troops had been suspended on 15 August with the announcement of Japan's acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration. All fighting did not cease, however, since it took many days, and in some cases weeks, for the official word of surrender to be carried along the badly disrupted Japanese communication channels.

Various devices were employed by the American commanders to transmit the news of final defeat to the dispersed and isolated enemy troops. Plane-strewn leaflets, loudspeaker broadcasts, strategically placed signboards, prisoner-of-war volunteers-all helped in persuading reluctant Japanese to submit themselves peaceably in conformity with the Imperial Rescript.

General MacArthur ordered General Styer, commanding the Army Forces of the Western Pacific, to receive the surrender of the Japanese units remaining in the Philippines. Rounding up the remaining enemy forces, however, was not a simple task. The remnants of the enemy scattered throughout the islands were split into a number of independent groups, all of which were operating from the comparative security of the mountainous terrain of the interior. Although these troops doggedly attempted to continue fighting, their resistance was disorganized and relatively ineffective. Malnutrition,

[458]

ESTIMATES OF JAPANESE STRENGTH AS OF AUGUST 1945

AREA |

G-2 ESTIMATE OF ENEMY GROUND FORCES1 |

JAPANESE STRENGTH ESTIMATES |

|||

ARMY2 |

NAVY3 |

CIVILIANS4 |

TOTAL |

||

| KURILES | 85,000 |

50,000 |

1,621 |

18,515 |

70,136 |

| KARAFUTO | 30,000 |

20,000 |

1,328 |

373,223 |

394,551 |

| RYUKYUS | 80,000 |

40,882 |

9,766 |

9,964 |

60,612 |

| FORMOSA | 260,000 |

128,080 |

46,713 |

307,147 |

481,940 |

| BONINS | 20,000 |

14,996 |

7,735 |

5 |

22,736 |

| KOREA | 365,000 |

274,200 |

29,431 |

712,583 |

1,016,214 |

| MANCHURIA | 615,000 |

760,000 |

1,185 |

998,815 |

1,760,000 |

| CHINA | 1,010,000 |

1,049,700 |

63,755 |

428,518 |

1,541,973 |

| INDO-CHINA | 90,000 |

90,370 |

8,914 |

6,900 |

106,184 |

| THAILAND | 50,000 |

106,000 |

3,051 |

5,300 |

114,351 |

| BURMA | 70,000 |

70,350 |

1,372 |

11 |

71,733 |

| MALAY-ANDAMAN SEA | 100,000 |

95,581 |

36,473 |

17,036 |

149,090 |

| SUMATRA | 75,000 |

59,480 |

4,984 |

4,300 |

68,764 |

| JAVA | 30,000 |

40,360 |

15,180 |

10,000 |

65,540 |

| LESSER SUNDAS, TIMOR | 25,000 |

17,500 |

4,238 |

450 |

22,188 |

| BORNEO | 20,000 |

24,850 |

10,879 |

7,000 |

42,459 |

| CELEBES, MOLUCCAS | 79,000 |

17,650 |

6,518 |

5,050 |

29,218 |

| PHILIPPINES | 25,000 |

97,3002 |

36,1513 |

17,651 |

151,102 |

| NEW GUINEA | 20,000 |

30,230 |

7,159 |

269 |

37,658 |

| BISMARCKS | 55,000 |

57,530 |

30,854 |

0 |

88,384 |

| SOLOMONS | 15,000 |

12,330 |

16,729 |

0 |

29,059 |

| MANDATES | 95,000 |

48,644 |

44,178 |

18,845 |

111,667 |

TOTALS |

3,214,000 |

3,157,683 |

406,890 |

2,941,636 |

6,516,959 |

1 Source: G-2, GHQ, SWPA, Monthly Summary of Enemy Dispositions, 31 July 1945, Plate 1.

2 Figures include civilians attached to the Army. In the case of the Philippines, approximately 4,200 civilians were included in the army strength figure. Source: Japanese First Demobilization Bureau Report, G-2 Historical Section, GHQ, FEC.

3 Figures include civilians attached to the Navy. In the case of the Philippines, approximately 20,365 civilians were included in the navy strength figure. Source: Japanese Second Demobilization Bureau Report, Historical Section, G-2, GHQ, FEC.

4 Source: Japanese Foreign Office Report, G-2 Historical Section, GHQ, FEC.

The G-2 estimates of enemy ground forces in the last phases of the war are in fair agreement with the figures for repatriated army and navy personnel subsequently developed by the Japanese Demobilization Bureaus, although air and navy remnants and civilians introduced unidentified variables. In areas of actual combat such as the Philippines and New Guinea where the G-2 estimates were concerned only with effective combat strength, the total number of army personnel including civilians attached to the army which were present in the area naturally exceeded the number of effectives estimated by G-2.

[459]

ESTIMATES OF ENEMY EFFECTIVE GROUND STRENGTH AND

REPATRIATION TOTALS: AUGUST 1945

AREA |

G-2 ESTIMATE OF ENEMY1 GROUND FORCES |

PERSONS REPATRIATED AND AWAITING REPATRIATION2 |

|||

ARMED FORCES |

CIVILIAN |

TOTAL |

|||

ARMY |

NAVY |

||||

| MANCHURIA | 615,000 |

679,057 |

1,092 |

1,270,330 |

1,950,479 |

| CHINA | 1,010,000 |

1,001,384 |

42,414 |

446,272 |

1,490,070 |

| KOREA | 365,000 |

215,405 |

23,237 |

651,328 |

889,970 |

| FORMOSA | 260,000 |

127,170 |

43,161 |

318,086 |

488,417 |

| OKINAWA | 80,000 |

46,360 |

9,913 |

6,141 |

62,414 |

| BONINS | 20,000 |

14,379 |

8,995 |

5 |

23,379 |

| PHILIPPINES | 22,0003 |

99,6734 |

8,4144 |

30,8024 |

138,8894 |

| INEFFECTIVES | 60,000 |

DISTRIBUTED THROUGHOUT COMBAT AREAS5

|

|||

| BORNEO | 20,000 |

16,049 |

6,088 |

3,422 |

25,559 |

| NEW GUINEA, CELEBES, AND LESSER SUNDAS | 115,000 |

113,545 |

33,560 |

5,636 |

152,741 |

| RABAUL | 55,000 |

64,356 |

31,356 |

74 |

95,795 |

| BOUGAINVILLE | 15,000 |

10,447 |

10,377 |

511 |

21,335 |

| CENTRAL PACIFIC | 95,000 |

58,493 |

39,652 |

18,818 |

116,963 |

| JAVA | 30,000 |

23,302 |

5,844 |

2,636 |

31,782 |

| MALAY-SUMATRA | 175,000 |

183,021 |

49,312 |

24,977 |

257,310 |

| THAILAND-BURMA | 120,000 |

177,437 |

2,744 |

4,600 |

184,781 |

| FRENCH INDO-CHINA | 90,000 |

86,095 |

8,144 |

4,695 |

98,934 |

TOTALS |

3,147,000 |

2,916,173 |

324,312 |

2,788,333 |

6,028,828 |

1 Figures from G-2, GHQ, SWPA, Monthly Summary of Enemy Dispositions, 31 July 45 (Plate 1).

2 Japanese Foreign Office as of 31 Dec 46.

3 G-2, GHQ, SWPA, Supplement to Monthly Summary of Enemy Dispositions, 23 Aug 45.

4 LETTER, HQ PHILRYCOM to Brig. Gen. Willoughby, 23 Jan 47.

5 There was a strong pre-war colony of Japanese in the Davao area of Mindanao (25,000) and in the Visayas and on Luzon (10-15,000).

The G-2 estimate of enemy ground forces in the Philippines-Bonins-Okinawa area in the last phases of the campaign are in fair agreement with the repatriation figures subsequently developed by the Japanese Foreign Office and the embarkation authorities in Manila, although air and navy remnants and civilians introduced unidentified variables.

The 205,000 effective combat troops in the Philippines in December 1944 had been reduced to 95,000 in less than four months, by April 1945, and had shrunk to 22,000 in August 1945, the balance were in hospitals, were convalescents, or were in static, isolated pockets of resistance scattered throughout the combat area. The classification of ineffectives is based on the known intelligence factor that there is a fairly steady ratio of killed to wounded. In the United States Army it was roughly one (1) to four (4) with a high percentage returning to the battlefield. In the Japanese Army, the ratio of recovered wounded was set lower because of callous handling by a fanatical and cold-blooded enemy who frequently killed his wounded when forced to retreat; wounded were not credited as "effective" on the battlefield for any particular date and period. In July-August G-2 estimated 22,000 effectives; 12,715 prisoners of war; 8-12,000 air and navy remnants; 50-60,000 ineffectives; 20-30,000 civilians of the pre-war Japanese colony in the Philippines, or an aggregate of 133,000 Japanese. The repatriation figures for January 1947 show an aggregate of 138,889.

[460]

disease, and improperly treated wounds had sapped their strength and taken a high toll in lives. On Luzon, the largest group of Japanese was concentrated around Kiangan, northeast of Baguio, fighting stubbornly in what had come to be called the "Yamashita Pocket." In this sector General Yamashita still held forth in command of the remaining forces of the Fourteenth Area Army, now reduced to a conglomeration of sick and wounded military elements, civilian employees, and refugees totaling about 40,000 men. In the Sierra Madre Mountains east of the Cagayan Valley, in the Zambales Mountains of Bataan, and in the dense areas of southern Luzon other thousands continued to struggle for survival.72 The jungles of Negros and Cebu and the wilds of Zamboanga and Mindanao provided temporary sanctuary for additional Japanese who roamed the islands of the South.73

In British New Guinea, V-J Day found the Australian 6th Division pushing some 8,000 of the enemy out of the Wewak area southward across the Sepik River. In Bougainville, an estimated 13,000 enemy troops were compressed into the southern coastal areas by the Australian 3rd Division, while another group of about 6,000 held out along the Buin Road in the south. In New Britain, approximately 47,000 Japanese were gathered at the tip of the Gazelle Peninsula. In Borneo most of the enemy units had retreated into the hills and jungles leaving the Australian 7th Division to occupy the cities along the coasts.74

In most cases, steps toward surrender took place as soon as the local Japanese commanders heard the Emperor's proclamation by radio. On Mindanao, the commanding officer of 4,000 air force personnel in the mountains about 30 miles east of Valencia in central Bukidnon Province began immediate negotiations to turn over his troops.75 Rear Adm. Takasue Furuse, in command of 1,500 Japanese naval personnel in the Infanta area of southern Luzon, initiated surrender talks with a guerrilla organization.76 Japanese forces on Bataan agreed to turn over their arms on 1 September while the enemy commander in the Cagayan Valley, Maj. Gen. Shintaro Yuguchi, signified that he would surrender his remaining units as soon as he received word from General Yamashita.77 Colonel Matsui, commander of Japanese forces in the southern part of the Cagayan Valley, arranged to turn over his men to the U. S. 27th Division on 2 September. Another enemy force, numbering more than 2,300, located farther north in the Dummun River and Capisayan District, sent word that it would give itself up to the Americans during the period of 2-6 September.78

The first direct contact made by United States forces with General Yamashita came on 26 August. Prior to that time it had been strongly suspected but not definitely known

[461]

PLATE NO. 133

Japanese Surrender throughout the Pacific

[462]

PLATE NO. 134

Japanese Strength Overseas, August 1945

[463]

that General Yamashita had remained with his troops in northern Luzon. Although attempts had been made to determine the general's whereabouts, his exact location had not been discovered. Filipino guerrilla reports to the effect that the Japanese general was present on the island were substantiated when a captured American pilot, who had been forced to bail out over enemy lines and who was subsequently released by the Japanese, later returned by air to point out the location of General Yamashita's headquarters.79

A message, signed by Maj. Gen. William H. Gill, commander of the 32nd Division, was dropped on 24 August requesting that contact be established to discuss surrender terms. At the same time, liaison parties were sent out by the 128th Infantry Regiment, 32nd Division, which by the middle of August had fought to within a few miles of General Yamashita's last stronghold. A second letter was dropped the following day directing General Yamashita to send a representative for the purpose of arranging the surrender of the Japanese forces which he controlled.80

The Japanese representative arrived at a 32nd Division outpost near Kiangan on 26 August with a letter from General Yamashita addressed to General Gill.81 Acknowledging the receipt of the two previous messages, General Yamashita stated that although he had received and transmitted an order to cease hostilities, he was without authority to surrender his troops until he was formally notified of the signing of the general surrender in Tokyo.

Further exchanges of messages, aided by an air-ground radio at the Japanese headquarters, indicated General Yamashita's willingness to send representatives to Baguio in about five days to make preliminary negotiations for the surrender of his 40,000 men in northwestern Luzon, more than one-third of whom, he declared, were either sick or wounded. This proposal was rejected, however, because of the excessive delay it would cause before the final terms could be agreed upon.

General Yamashita finally radioed to a liaison plane circling above his headquarters that he would meet American parties in Kiangan on 2 September, and that he would be ready to proceed to Baguio to sign surrender papers for the Japanese military forces in the Philippines.82

At 0900 on 2 September General Yamashita, together with his Chief of Staff, Lt. Gen. Akira Muto, and other staff officers delivered themselves to an escort of the 32nd Division near Kiangan. A second party, consisting of naval personnel under Vice Adm. Denhichi Okochi, also appeared on the scene to negotiate the surrender of the naval personnel in that area. From Kiangan the Japanese were transported by motor vehicle to Bagabag Airfield where a C-47 transport plane waited to take them to Baguio.83

General Styler, who had attended the general surrender ceremony in Tokyo, flew back to the Philippines on the morning of 3 September, accompanied by General Wainwright and General Percival. At noon the American and Japanese officers gathered in the former residence of the U. S. High Commissioner at Camp John Hay, Baguio. General Styler opened the conference with a terse statement of purpose: "We are gathered here today to consummate the surrender of the Japanese

[464]

armed forces in the Philippines. I shall ask my Chief of Staff, General Leavey, to commence the proceedings."84

Maj. Gen. Edmond H. Leavey directed that the instrument of surrender be read and then the necessary documents were signed by General Yamashita and Admiral Okochi at 1210 on the 3rd. General Leavy thereupon affixed his own signature, after which he announced the official acceptance of the surrender and the conclusion of the surrender ceremonies. Three hours later the Japanese delegates were flown to Nielson Airfield in Manila and then sent immediately to New Bilibid Prison, sixteen miles south of the city, for internment.

With General Yamashita's capitulation, subordinate commanders began turning over their forces in rapidly increasing numbers. On Cebu, 2,900 surrendered; another 1400 gave themselves upon Negros; local Japanese commanders on Mindanao began negotiations to surrender 4,000 troops in Davao Province, 2,000 in the Agusan Valley, and over 1,000 air force personnel in the mountains northwest of Davao.85

The long and brutal fighting in the Philippines was finished. An army of close to half a million Japanese had been overpowered, divided into ineffective remnants, and virtually annihilated. So completely cut off and separated had the various enemy units become that, for another year after the general surrender, patrols of the United States and the Philippine Armies continued to bring in straggling troops who had been unaware that their country had capitulated. On tiny Corregidor Island, twenty Japanese who had been hiding in a great jungle-filled ravine along the steep south shore cliffs did not surrender until 1 January 1946.

In other Pacific areas, the first large-scale surrender of Japanese forces came on 27 August, when Lt. Gen. Yoshio Ishii surrendered Morotai and Halmahera to the U. S. 93rd Division. Capitulation of Japanese units in the remaining parts of the Asiatic-Pacific Theater followed in quick succession. (Plate No. 133) In the Marianas, the Japanese commanders on Rota and Pagan Islands relinquished their commands almost simultaneously with the Tokyo Bay ceremony. While General Yamashita was yielding his Philippine Islands forces on 3 September, other Japanese garrisons were being surrendered in the Bonins, on Wake Island, in the Palaus, and at Truk in the Carolines, as well as at Hong Kong on the South China coast.86

Japanese commanding officers on Aquijan (Agiguan) Islands in the Marianas, and on Jaluit Atoll in the Marshalls, surrendered on 4 September, as did the Japanese on Ocean and Nauru Islands, to the west of the Gilberts. The same day Japanese forces at Singapore surrendered to the British aboard a warship in the harbor. On 5 September, Ulithi Atoll and the Yap garrison in the Carolines capitulated. The over-all surrender of Japanese forces in the Solomons and Bismarcks and in the Wewak area of New Guinea was signed on 6 September by Gen. Hitoshi Imamura on a British warship off Rabaul, once the center of Japanese power in the South Pacific.

Japanese naval and army forces in the Ryukyus officially capitulated on 7 September at the headquarters of Gen. Joseph E. Stilwell's Tenth Army on Okinawa. On the same day the enemy forces on the island of Kusaie gave up. In Borneo, Japanese forces in the south east surrendered at Balikpapan on the 8th,

465

while those in the northwest followed suit at Brunei Bay the following day.87