CHAPTER XII

FINAL SWPA OPERATIONS AND ORGANIZATION OF AFPAC

With his conquest of the Philippines, General MacArthur had thrust a solid wedge deep into the heart of Japan's war-acquired empire. His battling forces in the Pacific had advanced more than 3,000 miles through enemy-controlled sea and land areas without a single defeat.

Until mid-summer of 1944, the strategy of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in the war against Japan was designed to accomplish two general objectives. On the one hand, forces of the Southwest Pacific and the Pacific Ocean Areas would sever the enemy's lines of communications with the Netherlands East Indies and China, interdict the waters of Japan's Home Islands, and secure advance positions from which the invasion of the Japanese mainland could be launched should such a step "prove to be necessary." The other and equally important objective was to obtain bases from which the long-range bombers of the Twentieth Air Force could profitably strike important targets within the inner defense zone of the enemy's island possessions.1

In July 1944, the unbroken series of victories of the Allied forces and the increasing potential of the United States made it necessary to redefine and restate these over-all objectives in terms of the current situation. At that time, it was generally felt that, although it was possible to defeat Japan by sustained aerial bombing and the destruction of her sea and air forces, such methods would involve an unacceptable delay.

In view of the marked deterioration of Japanese resistance, the increasing superiority of Allied ground, air, and sea power, and the prospect of augmenting Allied strength in the Pacific after the surrender of Germany, it was concluded that the quickest and most effective way to win the Pacific War would be to seize the industrial heart of Japan by amphibious invasion. The actual landings, of course, were to be preceded by air and sea blockades, by intensive aerial bombardment, and by continued assaults against the remaining elements of the Japanese Navy and Air Forces.2 This concept became the guiding principle for the final year of the war.

During the early months of 1945, Japan's economic and military power was crumbling rapidly under the combined weight of the Allied offensives. The Japanese still had many divisions in the Southwest Pacific and Pacific Ocean Areas but the effectiveness of these forces was neutralized by blockade, isolation, and fast-dwindling supplies.

In the Southwest Pacific Area, eight Japanese armies had been either defeated or rendered powerless to conduct more than delaying actions. In the New Guinea-Solomons region, the Japanese Second, Seventeenth, and Eighteenth Armies had been crushed. In the Philippines, the Japanese Fourteenth Area and Thirty-fifth Armies were being rapidly annihi-

[363]

lated by the advancing forces of Generals Krueger and Eichelberger. In the Borneo-Celebes area, the Japanese Sixteenth, Nineteenth, and Thirty-seventh Armies were helplessly cut off and constituted no threat to General MacArthur's drive toward Japan.

In the Pacific Ocean Areas, the penetration of Japan's outer defense was completed with the seizure and occupation of Saipan, Guam, and Tinian in the Marianas. Operations had been launched in February to reduce the island of Iwo Jima and establish it as a base for fighter planes to support the Marianas-based B-29 bombers. With the capture of this important island in the Bonins a month later, the United States gained possession of a strategic military position only 750 miles from Tokyo and pushed its forces far into Japan's inner line of island fortifications. They would be pushed even farther with the projected assaults on Okinawa and the Ryukyus, the next operations scheduled for the Pacific Ocean Areas.

On the continent of Asia, the picture was no less grim for Japan. In Burma, Allied forces of the Southeast Asia Command, under Lord Admiral Louis Mountbatten, had the Japanese in full retreat by the end of January. The enemy's supply lines to the Asiatic coast had been cut by General MacArthur's successive landings in the Philippines and U. S. Navy operations in the China Seas. With the capture of the key port city of Rangoon on 3 May, the Burma campaign was virtually completed. Some enemy units were able to retreat eastward into Thailand and eastern Burma, but thousands of Japanese troops remained penned in isolated pockets without chance of escape.

In China, although the initiative for the most part still rested with the Japanese, their offensive power had fallen off considerably. Newly trained and re-equipped Chinese forces had begun to counterattack vigorously with encouraging results. In addition, the Japanese were becoming increasingly concerned about the safety of their Home Islands and were carrying out a general withdrawal of their troops from southern and central China in an effort to strengthen their positions along the eastern Asiatic coast.

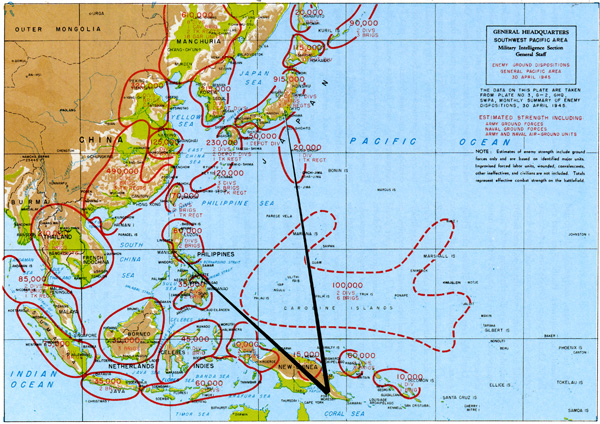

These millions of enemy troops in Asia and in the islands of the Pacific could never contract their lines to keep pace with the ever-narrowing arena of conflict. They were unable to conduct an orderly retreat in classic fashion to fall back on inner perimeters with forces intact for a last defense of Japan's main islands. It was a situation unique in modern warfare. Never had such large numbers of troops been so effectively outmaneuvered, separated from each other, and left tactically impotent to take an active part in the final battle for their Homeland. (Plate No. 104)

From his strategic position in Manila, General MacArthur began planning for the final invasion of Japan itself in accordance with the directives of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. In the absence of any indications to the contrary, it appeared that the command structure which had existed throughout the war in the Pacific would continue unchanged. General MacArthur believed, however, that the Pacific Command required considerable revision if ultimate victory were not to be needlessly jeopardized.

In December 1944, he expressed his views in a special radio to the War Department and stressed the necessity for reorganization. In his opinion, the command had to be greatly simplified and the completely arbitrary area boundaries, which originally had been conceived for defensive purposes, had to be abolished altogether.3 As matters stood, the U.S. Army ground, air, and service forces were unevenly

[364]

PLATE NO. 104

Enemy Ground Dispositions, General Pacific Area, 30 April 1945

[365]

and, in some cases, inequitably distributed between the Southwest Pacific Area and the Pacific Ocean Areas. Divided under two separate and independent commands, these forces could not be shifted with the speed and facility demanded by a rapidly changing battle situation nor could they be employed with maximum efficiency.

Until the campaign to liberate the Philippines, the individual operations in the Pacific had been conducted by relatively small forces, the size of a division or a corps. In the Philippines, however, an integrated army was employed on Leyte and two armies were required on Luzon. The invasion of Japan Proper would demand the use of an army group. General MacArthur proposed that a single commander should be responsible for the operational co-ordination of such large bodies of troops to permit their deployment to the best advantage.4

General MacArthur felt that the change in command structure should apply only to United States forces. In early January 1945, he recommended that army and navy Allied responsibilities continue as in the past, but that elements of the Australian Fleet should come under the operational control of the U. S. Navy.5 This would involve no difficulty since the respective elements of the two fleets had previously operated in close harmony.

Australian ground and air units had been co-ordinated with the United States forces for nearly three years. "Both from political and military points of view," General MacArthur declared, "it is considered inadvisable to effect a reorganization." He felt that the guiding principle to be followed was to retain under a single command all army forces which were engaged in a campaign in a theater against one enemy force. "Any deviation from this," he maintained, "merely weakens the potential, prolongs the war, and increases the cost in blood."6

He believed that the greatest efficiency could be secured by placing all naval forces under a naval commander and all army forces under an army commander, with the joint Chiefs of Staff exercising over-all direction and control. Only in this way could there be attained that complete flexibility and efficient employment of forces essential to victory. Unity of command for specific operations would be achieved by the creation of joint task forces. The task force commander in each instance would be chosen from the service having the paramount interest. General MacArthur also proposed that the same principle be applied to rear area troops and installations, with each service having its own supply and service organizations.

In general, such a determination of command would place the great land masses, such as Hawaii, New Guinea, and the Philippines, under the Army, and the outlying posts, such as Guam, Kwajalein, and Manus Islands, under the Navy. " This proposed organization," General MacArthur concluded, "will give true unity of command in the Pacific, as it permits the employment of all available resources against the selected objective."7

The Directives of 3 April 1945

On 3 April 1945, the Joint Chiefs of Staff issued a directive which reorganized the command structure in the Pacific. Under this directive, General MacArthur was designated Commander in Chief, United States Army Forces in the Pacific (AFPAC) in addition

[366]

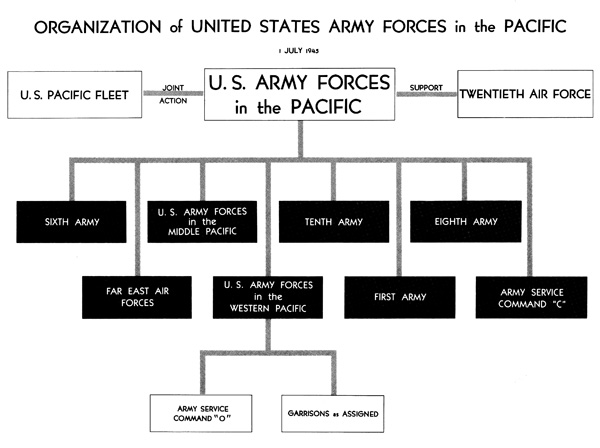

to Commander in Chief, Southwest Pacific Area and placed in administrative control of all army resources in the Pacific with the exception of the Twentieth (Strategic) Air Force, the Alaskan Command. and the army forces in the Southeast Pacific Area. All naval resources in the Pacific, except those in the Southeast Pacific Area, were placed under the administrative control of Admiral Nimitz.8

This reorganization, in essence, meant that the Joint Chiefs of Staff would exercise strategic jurisdiction over the whole Pacific Theater, assigning missions and fixing command responsibility for specific major campaigns. General MacArthur normally would be responsible for the conduct of all land operations and Admiral Nimitz, for sea operations. Each would have under his control the entire resources of his own services and each was authorized to establish joint task forces or appoint commanders to co-ordinate the conduct of operations for which he had been made responsible.

Thus, General MacArthur's proposal for two co-operating commanders in chief for the Pacific, one responsible for army forces and one responsible for navy forces, had in general been accepted. Actually, the Twentieth Air Force constituted a third distinct command, since it would continue to bomb Japan in accordance with directives from the Joint Chiefs of Staff to General Henry H. Arnold, Commander of all Army Air Forces.9

In a separate directive issued simultaneously with the reorganization order, General MacArthur was instructed specifically (1) to complete the occupation of Luzon and conduct such additional operations in the Philippines as would directly contribute to the defeat of Japan and the liberation of the Filipinos; (2) to make plans for occupying North Borneo, using Australian combat and service troops; (3) to plan and prepare for the campaign against Japan Proper, co-operating with Admiral Nimitz in the naval and amphibious phases of the invasion.10

Pacific Theater Command Reorganization

With the issuance of the directives of 3 April by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General MacArthur began a gradual regrouping of his forces in such a way that the necessary changes would be accomplished with a minimum disruption to operations already in progress.

Effective 6 April, the War Department announced the establishment of the United States Army Forces in the Pacific (AFPAC) with General MacArthur as Commander in Chief. Eleven days later, Lt. Gen. Robert C. Richardson, Jr., commanding the United States Army Forces in the Pacific Ocean Areas, was ordered to report his command to AFPAC for administration. Meanwhile, the Seventh Fleet was transferred from General MacArthur's control to the administrative command of Admiral Nimitz.11

Representatives of General MacArthur and Admiral Nimitz met at Guam early in April 1945 and agreed in general on the following principles to govern the reorganization of com-

[367]

mand in the Pacific:

1. General MacArthur and Admiral Nimitz would immediately assume administrative command of their respective services.

2. Each would release operational control of all of the other service, except those considered essential to the functioning, development, or defense of their respective geographical areas or to the success of previously scheduled operations. Resources to be released by each commander would include depots and supply systems of the other service.

3. Each commander would assume as rapidly as possible full supply responsibility for the forces of his own service.

4. The existing army and navy responsibilities within the Pacific Ocean Areas for the joint support of positions in the Marshalls, the Carolinas, the Marianas, and the Ryukyus would continue in effect until modified by mutual agreement.

5. Both commanders would establish as quickly as possible their respective command organizations necessary for the planning and conduct of the phases pertaining to the invasion of Japan.12

The administrative reorganization was quickly completed. The transfer of operational control was the more important phase of the reorganization but the Guam agreement did not specify any definite schedule for the actual shifting of forces. Both army and navy resources in the Pacific were still split between the areas as both services went ahead with plans and staff studies for future operations.

During this same period, army air forces in the Pacific were also regrouped for the final phase of the war. Before 3 April, there were three army air commands in the Pacific, each with a separate mission. The Far East Air Force, consisting of the Fifth and Thirteenth Air Forces, provided air support for operations in the Southwest Pacific Area. The Air Service Command, together with units of the Army Air Forces, performed the vital functions of maintaining adequate bases, keeping up a continual flow of parts and supplies, and providing rapid maintenance service. The Twentieth Air Force was an independent Pacific command, operating under the direct control of General Arnold. The super-bombers of the Twentieth Air Force carried out long-range and photographic missions in strategic support of operations in the Southwest and Central Pacific Areas.13

General MacArthur had recommended to the War Department on 14 May 1945 that the Pacific Theater be divided between the Far East Air Force (to include the Fifth, Seventh, and Thirteenth Air Forces) and the Twentieth Air Force (to consist of the long-range bombers in the Marianas and the Seventh Fighter Command on Iwo Jima). He also recommended that the Army Air Forces of the Pacific Ocean Areas be abolished and their personnel transferred to the Far East and Twentieth Air Forces.14

On 2 June, the Joint Chiefs of Staff announced a regrouping and reassignment of the various air forces in the Pacific.15 Headquarters of the Twentieth Air Force was scheduled to be transferred from Washington to Guam on 1 July and to be simultaneously redesignated the U. S. Army Strategic Air Force, under General Carl Spaatz. The XXI Bomber Command based in the Marianas took the title of the Twentieth Air Force and was placed

[368]

under Lt. Gen. Nathan F. Twining. The XX Bomber Command, scheduled for deployment in the Ryukyus, was redesignated the Eighth Air Force under the command of Lt. Gen. James H. Doolittle. Both the Eighth and the newly regrouped Twentieth Air Forces were incorporated into the command of the Strategic Air Force, giving General Spaatz, when he assumed command on 16 July, control of the mightiest fleet of super-bombers ever assembled.16

In July the Seventh Air Force, with headquarters in the Ryukyus, was transferred to General Kenney's Far East Air Force. This completed the concentration of the Army's main air power in the Pacific under two major commands, the Far East Air Force and the Strategic Air Force. The Fourteenth Air Force continued to operate in China as part of the Eastern Air Command under Lt. Gen. George E. Stratemeyer.

As plans for the invasion of Japan developed, General MacArthur made every effort to complete the liberation of the Philippines and carry out the projected assaults in the Netherlands East Indies as rapidly as possible. It was important to free his command for the planned operations against Japan, for it was logical to assume that his well-organized veteran staff and forces would constitute the nucleus of the great land and air team assigned to defeat the Japanese in their home islands.

The liberation of key areas in the Netherlands East Indies was a task which General MacArthur considered a United States obligation.17 In a radio to the War Department on 28 February, he outlined three main reasons for the necessity of a campaign in the Netherlands East Indies. First, he pointed out, the United States was obligated under the international agreement establishing the Southwest Pacific Area to undertake such a campaign. To overlook the Netherlands East Indies after freeing United States and Australian territories and restoring the former governments therein would represent a failure on the part of the United States to keep faith. Secondly, the re-establishment of the Netherlands East Indies government in Batavia would enhance the prestige of the United States in the Far East. With the occupation of Batavia, the Southwest Pacific Area would accomplish its mission except for the ever-necessary mop-up operations. General MacArthur felt that when the time came for such mopping-up the SWPA command should be dissolved and the responsibility for the conduct of civil affairs and for the further consolidation of territory should be turned over to the British and Dutch governments. Such measures would fulfill every obligation of the United States and, in addition, free General MacArthur from all future operational commitments outside of the areas necessary for the actual launching of the assault on Japan. A third reason was that an attack against the Netherlands East Indies sector would provide a remedy for the current comparative inactivity of the Australian troops. Operations in the New Guinea area did not require the full capabilities of the Australian forces and, until the final decisions were made regarding the employment of forces for the invasion of Japan, the Borneo sector furnished ideal action targets.18

A specific proposal to undertake the Netherlands East Indies operations had been made in the summer of 1944, when the British sug-

[369]

gested that a separate Commonwealth task force under a British commander be established. This plan contemplated the removal of Australia, the Indies, and Borneo from General MacArthur's command once the forces of the Southwest Pacific Area had been established in the Philippines. The British forces involved would then operate independently of General MacArthur.

The proposal was made originally to the Australian Prime Minister, John Curtin, at a Dominion conference in London.19 Mr. Curtin, however, recommended that the plan be rejected because of the existing Allied and Australian arrangements relating to command in the Southwest Pacific Area. He emphasized that Australian naval, land, and air units were included in the forces available to implement Allied strategy in the Pacific and were assigned to the Commander in Chief of the Southwest Pacific Area. He felt that there was danger of grave misunderstandings with the United States if the Australians were taken from General MacArthur's command and placed under an Empire commander. There was a tradition of successful association and collaboration between the Australian Government and General MacArthur's Headquarters, and the Australian Prime Minister was opposed to any change, except upon recommendation of the Combined Chiefs of Staff with the consent of the Australian Government.

General MacArthur was in full accord with the suggestion of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to accept all the British and Dominion forces that could be made available to him for use in the Pacific. He was completely opposed, however, to any proposition which might restrict the manner in which he would employ these forces. No steps should be taken which would impose an unjustifiable limitation upon his conduct of operations or unduly complicate the existing command channels. In a radio to the War Department on 27 August 1944, General MacArthur said: "To attempt to segregate such a force into an entirely self-contained command consisting of ground, naval, and air components would not only introduce a clash of command authority but would require the complete reorganization of the present set-up, wherein the Australian, New Zealand, and American forces are amalgamated along service lines and coordinated under my immediate control...."20 He also stressed that in other than exceptional circumstances, British or Dominion forces would serve under their respective commanders and would be given independent missions, but he re-emphasized that the co-ordination of all ground, naval, and air forces should remain under his control.21

To conduct the campaigns in the Netherlands East Indies, General MacArthur decided to use the Australian I Corps. The 6th, 7th, and 9th Divisions would be moved into the Hollandia-Morotai area to be staged for assaults along the coasts of Borneo.

Logistic factors made it impossible to execute these plans without some modifications. Difficulties were encountered in obtaining the necessary shipping to support the scheduled operations. In reply to a request for forty-eight cargo vessels, General MacArthur was advised that no additional tonnage was available. There were, however, ten trans-Pacific troop ships on hand which could be employed.22 These ships, together with a change

[370]

in the program for moving surplus supplies, service units, and bases from Australia, New Guinea, and other points in the South Pacific to the Philippines, provided a partial solution to the problem.

To cut shipping requirements still further, the original plan for the movement of the Australian troops was also changed. Only one division and a proportionate share of corps troops would be moved in heavy shipping; the remainder would be transported in amphibious craft. An initial schedule was established which called for the occupation of Tarakan Island, off the northeast coast of Borneo, on 29 April 1945 to provide land-based air support for subsequent operations against Balikpapan. The assault against Balikpapan, farther south on the same coast, would be launched on 22 May, while the move into the Bandjermasin area of southeastern Borneo was to take place on 1 June.

Air power based on Bandjermasin would, in turn, support the attack against Soerabaja, which was set for 30 June. If British carriers were available for support at this time, Soerabaja would be by-passed and the amphibious forces would strike directly at Batavia. The campaign would be concluded with one task force driving through Java and then through the remaining islands of the Indies within the Southwest Pacific Area, while a second task force moved up to occupy British North Borneo.23

Additional changes were required when it was decided not to relieve the Australian 6th Division from its task of reducing Japanese remnants in New Guinea. Lt. Gen. Sir Leslie Morshead, commanding Australian I Corps, was ordered to carry out the Tarakan and Balikpapan operations using only the 7th and 9th Divisions. It was also decided that priority should be given to the capture of the Brunei Bay area in British North Borneo, because this region would provide an excellent advance base for the British Pacific Fleet and would also serve as a source of raw rubber, a critical commodity.24 New operations instructions were issued incorporating these latest modifications. The Tarakan assault was moved back to 1 May; Brunei Bay was scheduled for attack on 10 June and the Balikpapan operations were set back five weeks to 1 July.

Final Southwest Pacific Operations: Borneo

Approximately 600 miles wide and 800 miles long, Borneo is the largest and yet one of the most sparsely populated of the islands in the Netherlands East Indies. The topography of the interior is hilly and mountainous and the entire island is covered with large tropical rain forests and swamps. Mechanized movement of any sort is virtually impossible except in small areas located mainly along the coasts.

During the early years of the war, Borneo was vitally important to the Japanese, both from an economic and a military standpoint. The enemy's selection of the northern oil fields as invasion points in 1942 indicated the emphasis which was placed on Borneo's petroleum supply. It was estimated that during the years of 1943 and 1944 this rich island supplied 40 per cent of Japan's fuel oil and 25-30 per cent

[371]

of her crude and heavy oils.25 Borneo's principal oil fields were located in the region of Samarinda on the east coast, on the island of Tarakan, and between Min and Seria at the northern boundary of Sarawak on the west coast.

In addition to its resources, the island occupied a strategic position on Japan's southern shipping lanes. Borneo's coasts were bordered by the two most important north-south sea routes off southeast Asia, the South China Sea to the west and Makassar Strait to the east. The Java Sea to the south provided east-west access to key ports throughout the Indies and to Malaya, Burma, and Thailand. Bases and harbors on the island's coasts served as staging, fueling, and transfer points for ships and planes moving along the lifelines of Japan's empire.26

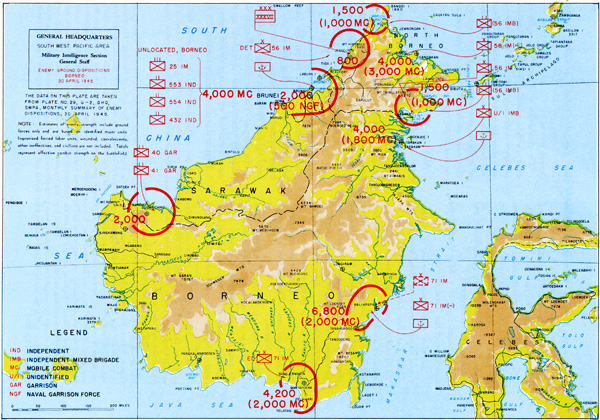

During the first months of 1945, the Japanese regrouped and shifted their forces to prepare the island for defense against an anticipated Allied attack. The firm and extensive occupation of Borneo by the Japanese made the procurement of intelligence an extremely difficult task and great care had to be exercised in sending Allied intelligence agents into the area. Despite the many handicaps, however, much valuable information on enemy strength and dispositions had been collected from agents of the Allied Intelligence Bureau and from other G-2 sources. During February, March, and April 1945, the estimates of enemy forces in the Borneo area remained fairly static, listing an aggregate of from 25,000 to 30,000 troops of the Japanese Thirty-seventh Army and miscellaneous naval units.27 (Plate No. 105)

Beginning their largest amphibious operation of the Pacific War, Australian troops sailed from Morotai on 27 April to launch the opening attack against Tarakan Island, off the northeast coast of Borneo. The assault against this island was the initial step in the Oboe operations of the over-all "Montclair" plan. By assaulting the important oil port of Tarakan, the Australians would strike their first blow to regain the rich colonial empire which had been seized by the Japanese in the dark days of January 1942. At that time, the oil storage tanks on Tarakan had been fired by the Dutch in a desperate effort to prevent their advantageous use by the invaders. Now again those same tanks, having been rebuilt by the Japanese, vanished in smoke and flame, this time under the bombardment of American and Australian-manned Liberators.

Backed by aerial assault and the devastating fire power of a naval task force composed of United States and Australian cruisers and destroyers, the Tarakan Attack Group under Rear Adm. Forrest B. Royal, arrived unopposed off Tarakan on the morning of 1 May. The reinforced 26th Infantry Brigade of the Australian 9th Division and a battalion of the Royal Netherlands Indies Army assailed the elaborate system of Japanese defenses at Lingk as, southeast of the Tarakan airdrome. Additional support was provided by artillery fire from Sadau Island, approximately six miles up the coast, which had been previously occupied by Australian commandos. Three days had been spent prior to the assault in sweep-

[372]

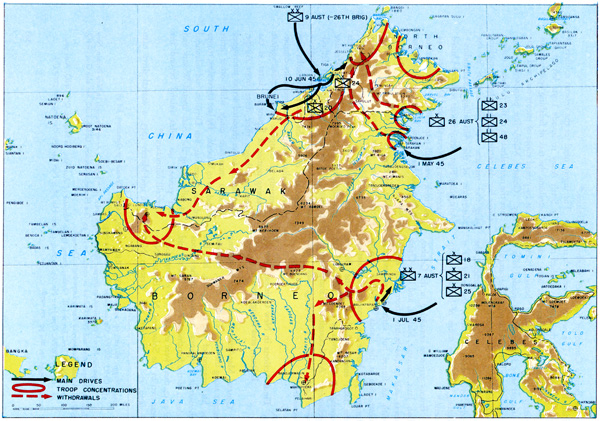

PLATE NO. 105

Enemy Dispositions on Borneo, 30 April 1945

[373]

ing the waters of mines, under the protective cover of naval guns. Steel rails, embedded in mud near the shore, and underwater barbed wire entanglements formed an additional obstacle which was extremely hazardous to move. Depth charges, land mines buried on the shore, oil pipes emplaced to spurt flame and smoke-all helped to form an elaborate and destructive beach defense.28

The communique of 3 May detailed the importance of the Tarakan move:

Australian ground forces from one of its most famous divisions, veterans of New Guinea and the Middle East, have landed on the key island of Tarakan, of the eastern coast of Borneo. Following intense air attacks by Royal Australian and Far East Air Forces and a four-day naval bombardment by units of the United States Seventh Fleet and the Royal Australian Navy, our troops in amphibious tanks and fast landing craft swept ashore near Lingkas, two miles east of Tarakan airfield. A beachhead was quickly established before the enemy garrison could offer effective opposition and our troops are advancing toward the airfield and town. There has been no enemy air or naval reaction.

Earlier denied the fruits of his rich Borneo oil and rubber conquests by our air and submarine blockade, his actual possession is now directly challenged. This operation virtually severs the enemy's holdings in the south. His forces in the eastern portion of the Netherlands East Indies, including the Celebes, Moluccas, Lesser Sundas, and other island outposts, are effectively isolated.

The establishment of this base will complete our chain of airfields extending from Luzon in the north to Darwin in the south, and enable our bombers to strike at will the enemy's forces anywhere in the Southwest Pacific Theater and constantly interdict his lines of supply and communication. Enemy shipping in these waters will be hunted down and destroyed as it has been already in the China Sea.29

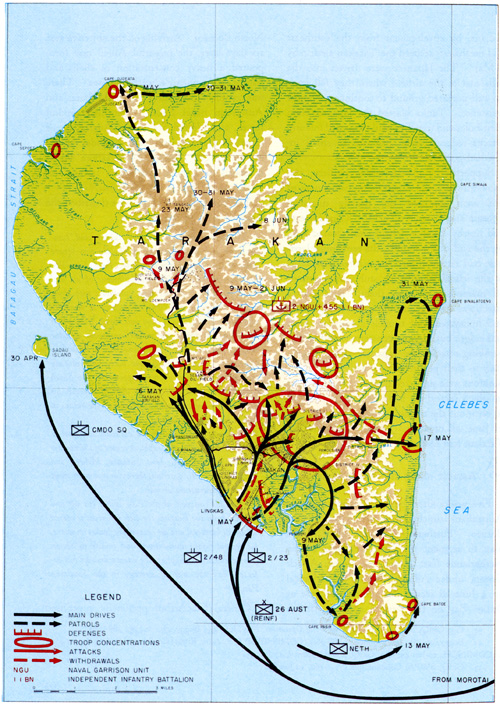

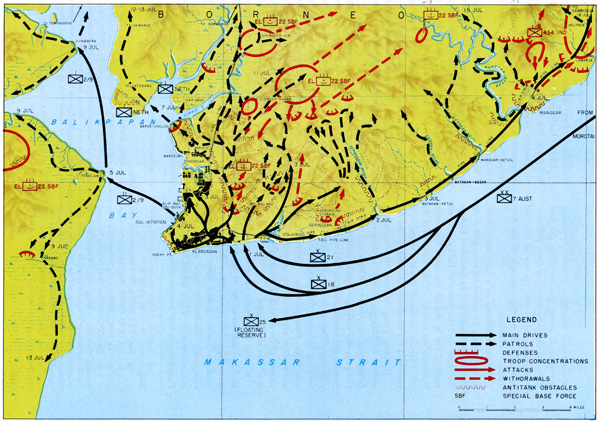

Although the strong enemy defense measures delayed the landing, they failed to repel it. The Australians went ashore at several places along the beach near Lingkas as the Japanese withdrew to prepared inland positions. (Plate No. 106) Aided by precision bombing of the Liberators and strong tank support, the Australian troops drove toward the island airfield, but as they approached Tarakan Town they began to meet increasingly fierce resistance. Heavy machine gun and mortar fire from a labyrinth of interconnecting tunnels and pillboxes opposed the advance. Fierce hand-to-hand fighting broke out along the ridges and in the jungle. Fanatic suicide charges were made by the Japanese defenders as they counterattacked with savage determination.30

Despite this strong enemy reaction, the Aus-

[374]

tralians, by envelopment from the southeast and northwest, secured the Tarakan airstrip by 6 May. The Japanese were driven into the hills east of the airfield where they fell back on well-prepared ground to continue a dogged resistance. Tanks blasted the Japanese from their holes and trenches while repeated infantry attacks reduced their defenses to small individual pockets.

Supported by planes, tanks, artillery, and flame-throwers, the Australians pushed onward and soon captured the heavily damaged Djoeata and Sesanip oil fields. Cape Djoeata and nearby Boenjoe Island were cleared and, by the end of the month, the remaining Japanese had retreated into the central mountains of the island where they stubbornly resisted all attempts to dislodge them. Attack after attack was made against the numerous pillboxes and honeycombs of tunnels along the crests and ridges but, despite constant shell-fire and bombing attacks, the Japanese clung desperately to their positions. In early June, these positions were subjected to low-level air attacks in which incendiary belly tanks were dropped to burn out the remaining enemy troops. By 21 June, all organized Japanese resistance on Tarakan had ceased.31

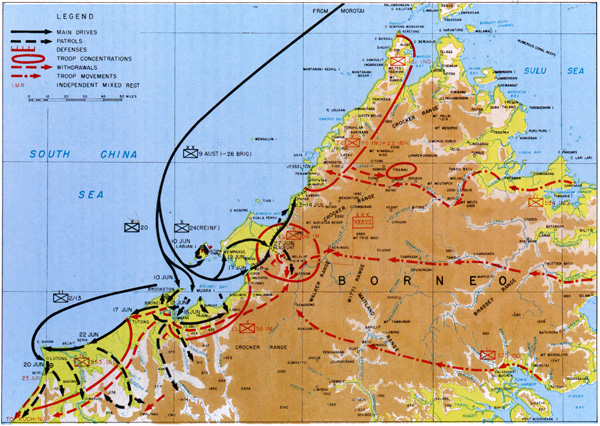

Five weeks after the Tarakan invasion, the Australians launched their second blow against Borneo. Furthering General MacArthur's plan to segment the Japanese forces in the Netherlands East Indies, the Brunei Attack Group, under Admiral Royal, left Morotai on 4 June to secure the great naval base at Brunei Bay on the western coast of British North Borneo. Arriving off the objective area six days later, the powerful Allied task force poured a heavy concentration of shells and bombs on the enemy's beach defenses. There was complete integration of United States and Australian naval forces, Australian ground forces, and United States and Australian air forces as the 10th and 24th Brigades of the Australian 9th Division swept ashore simultaneously on Labuan and Muara Islands and at Brooketon, just north of Brunei.32

The communique of 12 June described the strategic value of the objective:

The Brunei area is rich in oil, rubber, coal, lumber, iron and other resources and in the 500 square miles of its sheltered bay numberless ships of any size can ride at anchor. The establishment of air and naval facilities at Brunei Bay, combined with those in the Philippines, will complete a chain of mutually supporting strategic bases 1500 miles long, from which naval and air forces are within continuous effective range of the Asiatic coast from Singapore to Shanghai. Operations from the Philippine bases have already practically destroyed enemy shipping in the South China Sea and we shall now be able to interdict his overland lines of communication and escape routes in Indo China and Malaya.

At Brunei and Tarakan our columns stand not at the gates but at the geographical center of the enemy-occupied Celebes, Bali, Java, Sumatra, Malaya, and Indo-China. His garrisons there can now only await piecemeal destruction at will.

With his conquest in the East Indies cut off and isolated from the Empire, the rich resources rendered valueless, his naval and air arms in the Indies impotent, his ground troops immobilized and unable to obtain reinforcements or supplies, the enemy invader has definitely lost the war of strategy in the Southwest Pacific.33

General MacArthur personally supervised

[375]

PLATE NO. 106

Tarakan Operation, 1 May-21 June 1945

[376]

PLATE NO. 107

Brunei Bay Operations, 10 June-14 July 1945

[377]

the successful landings on Labuan Island and, together with General Morshead, Australian I Corps Commander, and General Kenney, Commander of Allied Air Forces, went ashore with the assault waves. "Rarely is such a great strategic prize obtained at such low cost," General MacArthur commented when he observed the success of the initial landings.34

Labuan (Victoria) Town was virtually destroyed by a naval bombardment three times greater than that which had been visited upon Tarakan. Japanese beach defenses lay shattered and only a few scattered parties of dazed enemy troops attempted to offer any resistance. The main opposition to the inland movement came in the form of glutinous mud which impeded infantry and vehicles alike. By nightfall, however, the Australians held the ruined town and the bomb-devastated airstrip. By 15 June, all organized resistance had been terminated on Labuan Island.35

On Brunei Peninsula, the advance southward proceeded rapidly. By 12 June, Australian troops had secured Brunei Airfield. (Plate No. 107) The town of Brunei fell the next day, after a swift march along the Cape and an amphibious movement across Brunei Bay. The Japanese had beaten a hasty retreat and only feeble counteraction met the Australian forces.

Accompanying the Australian troops into Brunei were members of the British North Borneo administration unit who were charged with restoring civil administration in the liberated areas of British Borneo and administering to the general welfare of the native population of Labuan and Brunei Peninsula. Positions in and around Brunei were consolidated and the drive continued southwest along the coast. Tutong, an oil refinery center located 35 miles south of Brunei Bay, was captured on 17 June. Meanwhile, a new and easy landing was effected by 9th Division troops at the port of Weston on the eastern shore of Brunei Bay.36

On 19 June, in the wake of an artillery bombardment from Labuan Island, 9th Division units in a shore-to-shore move landed at Mempakul, on the northeast shore of Brunei Bay. This unopposed landing gave the Australians complete control of the shores bordering both entrances into the bay. At the same time, the elements which had landed at Weston were pressing toward Beaufort, the strategic center on the single-track railway to Jesselton.37

Still another unopposed amphibious landing was made on 20 June at Lutong, the refinery center for the Seria and Miri oil fields, eighty miles down the coast from Brunei Bay. The town fell without a fight. Oil storage tanks

[378]

and refineries were captured intact, along with stores of abandoned equipment.38

The uninterrupted advance along the west coast continued toward Seria, 26 miles southwest of Tutong. The Australians reached Seria on 22 June and three days later took Miri, one of the oldest oil fields in Borneo.39 At Miri, 300 oil wells with a peacetime annual production of 1,318,000 barrels had been set afire by the Japanese and the 600,000-barrel storage tanks had been destroyed. Nevertheless, the capture of the northwest Borneo oil fields had been virtually completed, and Dutch oil experts were soon at work exploiting the vast liquid wealth still underground.40

Beaufort, an important railroad junction approximately 60 miles northeast of Brunei Bay, was captured on 27 June with little trouble and by the end of the month Australian forces were pushing along the Jesselton railway. The Australians now dominated 5,000 square miles of northwest Borneo and their lines stretched along the coast for 135 miles. Except for patrolling and mopping up, the North Borneo Campaign was over.41

The Brunei Bay operation had proceeded smoothly both in timing and execution. Nowhere on the mainland had the Japanese put up a concerted defense. The important oil fields of northwestern Borneo, strategic Brunei Bay, and the terminal of the northern narrow-gauge railway had been yielded by the enemy with only minor skirmishing. The Japanese on the west coast had shown little of the tenacity displayed on Tarakan, preferring instead to withdraw whenever possible. Rather than face the power of the Allied forces, many enemy troops had retreated from vital strategic areas to the mountainous interior, moving southward along the western coast of Kuching and into the area northeast of Brunei Bay.42

The third and most shattering blow in the reconquest of Borneo fell upon Balikpapan. Located roughly midway along Makassar Strait on Borneo's east coast, the Balikpapan area was one of the world's richest oil centers. When the Japanese attacked this great oil port at the beginning of 1942, the Dutch fired the storage tanks and blew up all installations in an attempt to prevent the exploitation of the oil fields by the enemy. Despite these efforts, the capture of Balikpapan had been a major and lucrative acquisition for the Japanese, whose well-prepared technicians and laborers had restored production facilities in record time.

On 26 June, in the largest amphibious operation under General MacArthur's command since the landings at Lingayen Gulf, the ships of the Balikpapan Attack Group, under Admiral Noble, sailed out of Morotai. Three days later, the invasion force stood off the shores of Balikpapan to begin the most intense pre-landing naval barrage ever put down in the Southwest Pacific Area.43 More than 45,000 rounds of five and six-inch shells were fired by

[379]

cruisers and destroyers of the United States Seventh Fleet and Australian and Dutch Fleet elements. This terrific shelling had been preceded by twenty days of bombing by the Royal Australian Air Force and the U. S. Fifth and Thirteenth Air Forces. Averaging 200 tons of bombs a day, the Liberators hammered the oil port relentlessly and effectively neutralized all enemy airfields within range of Balikpapan. Fifteen days prior to the landings, mine sweepers were at work clearing the surrounding waters of the thousands of mines that had been laid successively by the Dutch, the Japanese, and the Allies as the course of the war changed with the years.44

On 1 July, the 18th and 21st Brigades of the Australian 7th Division charged ashore in the region of Klandasan. (Plate No. 108) The 25th Brigade was held as a floating reserve to be employed according to operational developments.

The communique for 2 July announced the strategic implications on the landings:

Australian ground forces have made a third major landing on the vast island of Borneo....

Swiftly following our seizure of Brunei Bay on the northwestern coast and Tarakan on the northeastern, the enemy's key Borneo defenses are now isolated or crushed, and his confused and disorganized forces are incapable of effective strategic action. The speed, surprise, and shock of these three operations have secured domination of Borneo and driven a wedge south splitting the East Indies.

Strategic Makassar Strait, gateway to the Flores and Java Seas, is now controlled by our surface craft as well as by air and submarine. Development of already existing air facilities at Balikpapan will enable our aircraft of all categories to disrupt and smash enemy communications on land and sea from Timor to Sumatra. The whole extent of Java and the important ports of Soerabaja and Batavia are now within easy flight range and subject to interdiction. Our shipping can now sail with land-based air cover to any point in the Southwest Pacific.

It is fitting that the Australian 7th Division which in July three years ago met and later turned back the tide of invasion of Australia oil the historic Kokoda Trail should this same month secure what was once perhaps the most lucrative strategic target in our East Indies Sector and virtually complete our tactical control of the entire Southwest Pacific.45

Landing at Klandasan Beach, two miles from Balikpapan, the Australians moved rapidly inland and within six hours had established a beachhead three miles in length. Aircraft and naval gunfire formed a barrage ahead of the advancing troops as the Japanese withdrew from the beach areas. Oil tanks became flaming infernos when supporting warships hurled shells into the Japanese defenses and into the town and the extensive oil storage areas.46 General MacArthur, landing on the beach with the last wave of assault troops, declared as he strode ashore, " I think today we settled the score of the Makassar Strait affair of three and a half years ago."47

Meeting only sporadic opposition, the Australians seized Mount Malang and the high ground overlooking the town. The advance continued eastward along the coast toward the

[380]

PLATE NO. 108

Balikpapan Operation, 1-18 July 1945

[381]

Japanese-built Sepinggan Airfield, by-passing several small enemy pockets along the way. Elaborate defenses, including large pillboxes, were abandoned by the Japanese as they fled before the fast-moving onslaught of the Australian 7th Division.

Resistance stiffened on 2 July, but a determined drive up the coastal highway gained the town of Sepinggan and its 5,000-foot airstrip. The next day, the center of Balikpapan was captured and by the 4th the entire Klandasan Peninsula was secured. Other elements of the 7th Division advanced steadily inland and enveloped the Pandansari oil refinery area.48

Thrusting along the coast, the Australians reached the Manggar airstrip, 13 miles east of Balikpapan, on 4 July.49 Ridges and gullies along the way were criss-crossed with Japanese trenches and tunnels while the hills were dotted with log pillboxes and bunkers, but flame-throwing tanks and field guns drove the Japanese from their positions. Destroyers and rocket ships moved inshore to deliver fire in support of the advance as heavy fighting developed west of Manggar.

A series of overwater movements and shore landings was carried out to tighten the hold on strategic Balikpapan Bay, while enemy cave positions farther inland were methodically eliminated. Backed by naval gunfire, Australian troops on 5 July landed unopposed at Penadjam on the western shore of the bay. Netherlands East Indies forces made two amphibious landings on the northern shore of Balikpapan Bay on 7 July.50 Two days later, 7th Division troops made another overwater movement to Djinabora, 4 miles north of Penadjam, and established complete control over the Balikpapan Bay shore areas.51

By 11 July, the Australians had forced the enemy from the Pandansari area and had driven a wedge inland northeast of Balikpapan along the Balikpapan-Samarinda road. In the nearby hills, enemy cave positions were gradually eliminated. Although stubborn delaying action was encountered along the Balikpapan-Samarinda highway, the resistance met did not match the caliber of previous campaigns against the Japanese.52

Northeast of Manggar, elements of the 7th Division moved along the road toward Sambodja without enemy contact. Other Australian units drove inland, expanding their control over the entire Balikpapan area. On 18 July, the Australians secured Sambodja, a huge oil field 28 miles northeast of Balikpapan, against steadily weakening resistance by the bewildered and demoralized enemy. Further action in the Balikpapan area consisted of little more than mop-up skirmishes with scattered enemy remnants who continued to retreat into the jungles.53

By the end of July, scarcely three months after the fighting had begun, every objective

[382]

of the Borneo Campaign had been attained. (Plate No. 109) The swiftly moving 7th and 9th Divisions had thoroughly crushed the enemy. The Japanese defenders were completely defeated and their beaten, sickly remnants were driven into the wooded hills of the interior to live off the land. The campaign had netted two great naval bases-Brunei Bay and Balikpapan, seven important airfields, the rich Seria-Miri oil wells, the refineries at Lutong, and huge stores of Japanese equipment.54

Enemy garrisons remaining in the Celebes, Bali, Java, Sumatra, Malaya, and Indo-China areas were further isolated from their empire with no future but surrender or eventual destruction at the hands of Allied mop-up forces. Just before the Japanese capitulation, the total enemy casualties in the Borneo operations were given at 5,693 dead and 536 prisoners. Allied casualties, in sharp contrast, were 436 killed, 3 missing, and 1,460 wounded.55

Final Actions in New Guinea, New Britain, and Bougainville

General MacArthur's successful by-passing tactics along the New Guinea coast, followed by his invasion of the Philippines, had left thousands of Japanese contained in the various islands of the Southwest Pacific. At the end of 1944, there were over 110,000 enemy troops scattered in the Solomons, New Britain, New Ireland, and in Eastern and Western New Guinea.56

The urgent need for the veteran soldiers of the Sixth Army to invade Leyte left to the Australians the task of finishing operations in these by-passed zones of enemy-occupied territory. General MacArthur proposed to continue the neutralization of the pocketed enemy forces but the tactical methods for accomplishing this mission were left entirely to the discretion of the Australian commanders.57 Australian First Army troops replaced United States forces in November and December 1944 and took over full responsibility for operations in New Guinea, New Britain, and Bougainville.58

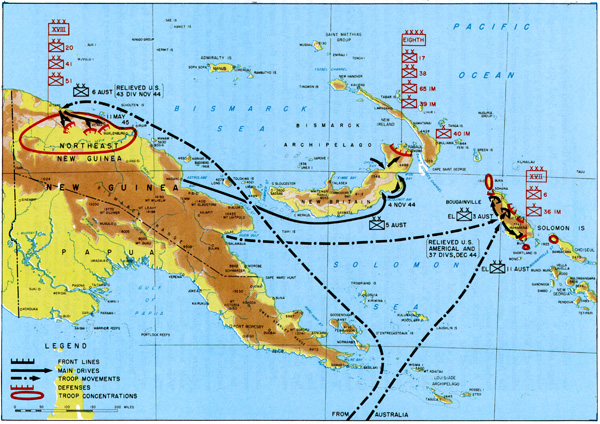

The fighting in all three of these areas followed the same general and unvarying pattern. (Plate No. 110) Small enemy garrisons, cut off from supplies or reinforcements and clinging desperately to their defensive positions had to be painstakingly and methodically eliminated. Activity in the Wewak-Aitape area during the first two months after the Australians assumed responsibility consisted mainly of energetic patrol actions against harassing parties of Japanese. Later, as the Australians began their drive from Aitape, some enemy forces retreated across the rugged Toricelli mountain range while other units withdrew to Wewak. By late December, troops of the Australian 6th Division had advanced 34 miles along the coast toward Wewak and had pushed 40 miles inland beyond the Toricelli Mountains.59

In mid-March 1945, a coastal drive east-

[383]

PLATE NO. 109

The Borneo Operations, May-July 1945

[384]

PLATE NO. 110

Mop-Up Operations in Eastern New Guinea, New Britain, and Bougainville

[385]

ward resulted in the capture of the But and Dagua airfields.60 A month later the coastwise advance had reached a point within twenty miles of Wewak. Meanwhile, the inland offensive encountered determined resistance as the Australians approached the heavily defended Maprik area.61

A general attack against Wewak was launched on 10 May. Supported by tanks, artillery, and air and naval bombardment, the Australians drove westward against the Japanese Eighteenth Army's last main positions on the shore of Eastern New Guinea. An amphibious landing on the east coast of Cape Moem cut the enemy's coastal escape route and menaced Wewak from the east. After fierce fighting, the Wewak Peninsula was wrested from the Japanese on 11 May. The whole Wewak coastal area was then cleared when the eastward and westward drives joined on 23 May. Except for a pocket remaining at Maffin Bay, the New Guinea coastline was free of enemy resistance as far west as Geelvink Bay.62

New Britain was returned to Australian control early in November 1944. By-passing positions seized earlier in the war, troops of the Australian 5th Division landed first at Jacquinot Bay on the south coast of the island to place themselves only 100 miles from the Japanese stronghold at Rabaul. Later they made another landing across the island at Wide Bay which cut this distance in half. The Royal Australian Navy and Air Force supported the operations.63

Drives along the north and south coasts forced the Japanese into the mouth of the narrow Gazelle Peninsula and bitter fighting ousted them from their strong positions in the Open Bay area by April 1945. Although the Australians carried out vigorous patrolling and fought occasional skirmishes with the enemy, their activity was generally limited after May. The remaining Japanese forces were effectively confined within the limits of the Gazelle Peninsula.

A campaign to destroy the Japanese Eighth Area Army's heavily garrisoned bastion at Rabaul was made unnecessary by Japan's capitulation and surrender. Such an operation would undoubtedly have proved bitter and costly. Post-war investigation disclosed that the high ground around Rabaul was honeycombed with strong underground defenses heavily stocked with ammunition and explosives.

Most of Bougainville and all of Buka Island to the north were still under the control of the Japanese Seventeenth Army when the Australians took over the defensive perimeter at Empress Augusta Bay in November 1944. After relieving United States forces, Australian First Army troops expanded the perimeter considerably and began a gradual elimination of enemy units on the island. They moved along the western coast and across the island toward Numa Numa, the main enemy base on the east side of the island. Stubborn resistance was encountered in all sectors, particularly in the central areas where the Japanese lines of communications to the north were seriously threatened.

In their drive northward toward Buka Passage, the Australians were faced by a well-entrenched enemy at Tsimba Ridge in the northwest part of the island. In February, heavy artil-

[386]

lery barrages and fierce bombing and strafing at tacks by Australian and New Zealand airmen were instituted to dislodge the Japanese from their positions. During the same month, the Motupena Peninsula in the southwestern part of the island was completely occupied against light opposition.64

To speed the northward advance, Australian units made two landings in March on the Soraken Peninsula in the northwestern sector. A drive across the peninsula to the east coast compressed the Japanese into the northern tip of the island and effectively severed their lines of communication.65 The Soraken Peninsula was cleared of the enemy by May as the Australians moved northward toward Buka Passage. The advance to the east coast in the central part of the island reached Numa Numa. In the south, meanwhile, the thrust toward Buin progressed slowly against bitter opposition.66

During June, successive enemy pockets of resistance were steadily eliminated. To the north, active patrolling was carried out as small bands of raiding Japanese were annihilated. In the central and southern sectors the Australians increased pressure on the strong enemy positions emplaced along the Mibo River. The situation remained generally static thereafter with the defenders being gradually compressed to the south and east along the coastal sectors and north to Buka Island until the surrender.67

The final mop-up of the northeast New Guinea, New Britain, and Bougainville areas which were spread over 1,000 miles of land and water had been a tedious task. At the end of July 1945, General MacArthur's Headquarters in Manila announced that a total of 12,385 Japanese had been killed on these islands since the first of the year.68

Pending termination of the European conflict, for which the amphibious invasion of Japan waited, consideration was given to other possible operations which would require relatively small resources and would not interfere with preparations for the main effort. A large-scale offensive by United States forces on the Asiatic continent was deemed impractical because of difficult terrain, inadequate communications, and strong Japanese ground force opposition. The China coast, however, had objectives suitable for limited operations subsequent to the conquest of the Ryukyus. Seizure of positions below Shanghai would tighten the blockade of Japan from the south while occupation of areas north of Shanghai would cut Japanese lines of communication to Korea and Manchuria across the Sea of Japan and the Yellow Sea. The Shantung Peninsula, the Shanghai area, the Ningpo Peninsula, and the Korean Archipelago, all within range of Tokyo, offered favorable bases for the intensification of aerial bombardment.69

Certain operations in the North Pacific could be undertaken simultaneously. Existing schedules called for the defeat of Japan without the assistance of the Soviet Union. The possible use of United States and Russian heavy bombers and long-range fighters from

[387]

bases in Siberia and the Maritime Provinces was strategically desirable but not considered essential at any time. During late 1944, tentative plans were made for securing a water route through the Sea of Okhotsk to Russian ports once the Russian entry into the war against Japan became imminent. These plans were dropped, however, because necessary resources were not available and also because such a maneuver might have precipitated the premature entry of the Soviet Union into the Pacific War.70

The Soviet Union was not disposed to enter the war until after the defeat of Germany. The most advantageous time, from the Russian point of view, would be after United States forces made their initial lodgment in Kyushu, drawing Japanese troops from Manchuria. Conversely, the most favorable time from the American standpoint would be three or four months after the surrender of Germany and about three months prior to the invasion of Kyushu. This correlated timing would have ensured that the Soviet Union had sufficient strength to eliminate the possibility of a successful Japanese counterattack which might disrupt the Russian advance or necessitate aid from the United States. At the same time, it would prevent the displacement of hostile troops from Manchuria, Korea, and North China to Japan's Home Islands.71

Toward the end of 1944 and in early 1 945 the question of Russian intervention in the Pacific appeared occasionally in international discussions. The political, economic, and military effect of such intervention seemed to have become a vital factor in the hitherto secret understandings. From the viewpoint of GHQ, AFPAC, any intervention during 1945 was not required. The substance of Japan had been gutted; the best of its army and navy had been defeated; the Japanese Homeland was at the mercy of air raids and invasion. Although General MacArthur in 1941 had urged Russian participation to draw the Japanese away from the South Pacific and Southeast Asia, by 1945 such intervention had become superfluous.

In February 1945, the combined Chiefs of Staff favored an invasion of Kyushu-Honshu in late 1945 or early 1946, following the defeat of Germany. The date of Germany's capitulation was estimated, at the earliest, as 1 July 1945 and, at the latest, as 31 December 1945. It was also estimated that Japan would be defeated eighteen months after Germany.72

Additional positions to further the blockade and air bombardment of Japan would be seized following the Okinawa operation and prior to the invasion of Kyushu. The air bombardment of Japan would then be intensified, thereby further reducing Japan's major military forces and creating a situation favorable to the direct invasion of the industrial heart of Japan via the Tokyo Plain.

General MacArthur considered that an invasion of Kyushu was undoubtedly the most advantageous operation to undertake in the year 1945. He was convinced that any movement or allocation of resources that did not directly contribute toward this goal should be eliminated. He felt that the full power of the combined resources-ground, naval, and air-in the Pacific was sufficient to initiate such an operation by November 1945, regardless of the status of redeployment from Europe and without consideration of Russia's entry or non-entry into the Pacific war.

The real crux of the problem was the supply

[388]

situation but this, General MacArthur thought, could be solved if, as sole commander, he were given a high degree of operational authority to reorganize all army supply agencies in the Pacific. To provide the required allotment of service troops for the invasion of Kyushu there would have to be a ruthless thinning of rear areas and a comprehensive pooling of army and navy resources. It would be necessary for the Navy to assist in moving forward service troops, equipment, and supplies from New Guinea and the South Pacific. The War Department would have to allocate additional shipping for the amphibious movement and for the direct resupply to Kyushu.73

The issuance of a Joint Chiefs of Staff directive on 25 May clarified the command organization for the operations against the main island of Japan and set the date for the "Olympic" invasion of Kyushu at 1 November 1945.74 This target date allowed about five months for the preparation of the ground and amphibious forces and for the completion of the necessary logistic arrangements.

The first step taken was a reorganization of the army command. General MacArthur assumed the responsibility for the Japanese campaign as Commander in Chief of the newly constituted United States Army Forces in the Pacific rather than as Commander in Chief of the Southwest Pacific Area, the capacity in which he had directed all previous operations. The duties and responsibilities of the two positions were quite different. As Southwest Pacific Area Commander, General MacArthur had exercised operational but not administrative control over ground, air, and naval forces of the United States, Australia, and the Netherlands East Indies. Simultaneously, as Commanding General of the United States Army Forces in the Far East, he was administrative commander of the Sixth and Eighth Armies, the Far East Air Force, and the United States Army Services of Supply, all of which comprised the major American elements in the Southwest Pacific.

As Commander in Chief, United States Army Forces in the Pacific, General MacArthur's responsibilities were expanded to include both operational and administrative control over all United States Forces in the Pacific except the Twentieth Air Force and certain troops in Alaska and the Southeast Pacific Area. (Plate No. 111) The need for a separate administrative headquarters was ended. The organization of the United States Army Forces in the Far East was discontinued except as a nominal agency to permit the approval of certain financial expenditures in the Philippines as required by law. The United States Army Forces in the Western Pacific (AFWESPAC), a command subordinate to AFPAC, was created at Manila on 1 June 1945, under the command of Lt. Gen. Wilhelm D. Styer. This command was designated to take over the functions of the United States Army Forces Service of Supply and some of the functions of the deactivated USAFFE. AFWESPAC would control all American Army forces within the Southwest Pacific Area except major combat commands. It would also be responsible for the logistical support of operations, except for air corps technical supplies.

A similar organization, the United States Army Forces in the Middle Pacific (AFMIDPAC) was established on 1 July under Lt. Gen. Robert C. Richardson, Jr. This command was formed to take over the forces and instal-

[389]

PLATE NO. 111

Organization of United States Army Forces in the Pacific

[390]

lations of the United States Army Forces of the Pacific Ocean Areas and the Hawaiian Department as they were released from the operational control of Admiral Nimitz.75

Okinawa, strategically the most important island of the Ryukyus, had been invaded by the Tenth Army's XXIV Corps and the Marine III Amphibious Corps on 1 April 1945. After some of the heaviest fighting of the Pacific War in which severe losses in men and ships were suffered by both sides, the campaign was declared officially closed on 21 June, except for mopping-up disorganized enemy remnants.

With the capture of Okinawa, the Allies had acquired new airfields from which almost any type of plane could operate against targets in Japan's Home Islands. Okinawa also provided several excellent anchorages within 350 miles of southern Kyushu. Japan had lost the last outer fortress protecting her communication lines to Korea, the Chinese mainland, and to the Indo-China and Singapore areas. Formosa was cut off and left helpless against Allied air and sea attack.

On 19 July, Admiral Nimitz was directed to transfer to General MacArthur by 1 August control of the American-held areas in the Ryukyus and all army forces there, including the Tenth Army. At that time, General MacArthur would assume responsibility for the defense of these areas and for the logistical support of the Strategic Air Forces based there. Admiral Nimitz would retain command of naval forces, installations, and bases.76

By these reorganizations, General MacArthur was finally given operational as well as administrative control of all army resources in the Pacific, with the exception of General Richardson's AFMIDPAC and certain other garrison and service troops in the islands of the Pacific Ocean Areas. On 28 July, General MacArthur attempted to secure operational responsibility of these forces also, so that all army forces in the Pacific would be under one commander. He again recommended that the area boundaries in the Pacific be abolished because they had long ceased to serve any useful purpose, were patently artificial, and complicated the proper strategic and tactical handling of the United States forces in that theater of operations. He pointed out that the existing demarcations prevented unification of command within each of the services and thus were contrary to the operational principles of the theater.77 General Richardson, however, continued to function under dual control until the end of the war, with responsibilities to the commanders in chief of both services.

Division of the Southwest Pacific Area

The final disposition of the Southwest Pacific Area presented another problem that had to be resolved before General MacArthur could concentrate upon his responsibilities as Commander in Chief of the United States Army Forces in the Pacific. He had recommended on 25 February 1945 that the Southwest Pacific Area be dissolved with the completion of the Australian operations in the Netherlands East Indies. The consolidation of liberated territories and the conduct of civil affairs could then be transferred to British and

[391]

Dutch authorities to permit the concentration of American resources for the invasion of Japan.78

On 27 June, General MacArthur again recommended that the areas south of the Philippines be removed from United States control, turned over to the British, and handled by them in co-ordination with the Dutch. As an initial step, all ground, naval, and air forces other than United States forces would be released and transferred to the commanders designated. Thereafter, ports, airfields, and bases would be released progressively as their use by United States forces was terminated.79

Negotiations with the British for this purpose were opened in April. The British at first were reluctant to put an additional burden upon the Southeast Asia Command until after 1 January 1946. It was expected that Admiral Mountbatten by that time would have completed the recapture of Singapore. The British were also uncertain of the extent to which they could absorb the great numbers of men and ships and the vast quantities of materiel which would be transferred when the withdrawal of United States control in this area was effected.80

The Americans believed, however, that Australian and Dutch units could garrison the Netherlands East Indies without affecting Admiral Mountbatten's planned operations. The final decision was made at the Potsdam Conference. The Southeast Asia Command was enlarged to include Borneo and the Celebes and Admiral Mountbatten was directed to assume control as soon as practicable after 15 August. The Southwest Pacific Area was continued as an Allied command under General MacArthur but its operations were limited to minor rear area activities.81

As the date for the transfer of responsibilities approached, General MacArthur dispatched messages to the Governments of Australia, New Zealand, and the Netherlands in tribute to the Allied troops who had fought under him in the arduous campaigns of the Southwest Pacific. To the Australian soldiers, sailors, and airmen, he wrote:

Since the 18th of April 1942, it has been my honor to command you in one of the most bitter struggles of recorded military history-a struggle against not only a fanatical enemy under the stimulus of early victory, but the no less serious odds of seeming impenetrable barriers of nature-a struggle which saw our cause at its lowest ebb as the enemy hordes plunged forward with almost irresistible force to the very threshold of your homeland.

There you took your stand and with your Allies turned the enemy advance on the Owen Stanleys and at Mine Bay in the fall of 1942, thus denying him access to Australia and otherwise shifting the tide of battle in our favor. Thereafter, at Gona, Wau, Salamaua, Lae, Finschhafen, the Huon Peninsula, Madang, Alexishafen, Wewak, Tarakan, Brunei Bay, and Balikpapan, your irresistible and remorseless attack continued.

Your airmen ranged the once enemy-controlled skies and secured complete mastery over all who dared accept your challenge-your sailors boldly engaged the enemy wherever and whenever in contact in con-

[392]

temptuous disregard of odds and with no thought but to close in battle so long as your ships remained afloat.

These, your glorious accomplishments, filled me with pride as your commander, honored for all time your flag, your people and your race, and contributed immeasuably to the advancement of the sacred cause for which we fought.

I Shall shortly relinquish this command which, throughout its tenure, you have so loyally and so gallantly supported. I shall do so with a full heart of admiration for your accomplishments and of a deep affection born of our long comradeship in arms. To you of all ranks, I bid farewell.82

Demobilization, Redeployment, and Replacements

When the United States Eighth Army assumed the task of cleaning out remnants of the Japanese defenders in the Philippines, General Krueger's Sixth Army was released to prepare for the invasion of Kyushu. During a two-year period, the Sixth Army had conducted 12 major operations, involving 21 separate amphibious landings, and had advanced a cumulative distance of approximately 3,000 miles. Many of its units were understrength as a result of battle losses and the readjustment of high-point personnel. To remedy these shortages, veteran troops from the European Theater were to be obtained as replacements.83

Before the war ended in Europe, plans had been made for a partial demobilization of the Army immediately following the defeat of Germany. On 16 April 1945, General Marshall urged all theater commanders to plan for the movement of the maximum number of troops likely to be eligible for discharge to the United States immediately upon the termination of the war in Europe.84 After the German capitulation, it was estimated that 2,000,000 men would be discharged during the ensuing year. Approximately 300,000 of these would be drawn from the Pacific Theater.85

Under the initial adjusted service rating score of 85, the Sixth Army, which was being prepared for the invasion of Kyushu, would lose 23,000 enlisted men. In addition, there were 20,712 officers in the theater with 85 points or more who were eligible for discharge, even though there was already an acute shortage of officers for combat units. To correct this situation, plans were made to ship 10,000 selected enlisted men and 4,500 officers directly from Europe to the Pacific Theater in September.86

General MacArthur and his staff were opposed to a further lowering of points prior to the invasion of Kyushu, as this would release veteran non-commissioned officers and specialists and would endanger projected operations. There was not sufficient time to replace personnel of invasion units who had critical scores slightly below 85, nor time to train the replacements if they were furnished. Recognizing the urgency of the situation, the War Department agreed to retain the 85 score temporarily to meet operational requirements in the Pacific.

The Southwest Pacific Area had been handicapped continuously by a shortage of personnel during most of the war. Only after Germany's defeat could sufficient forces and shipping be accumulated to make the final effort against Japan. When General MacArthur became Commander in Chief, AFPAC, on 6 April

[393]

1945, the combined forces under his new command consisted of 1 airborne division, 1 cavalry division, 19 infantry divisions, and approximately 53 air groups. Proposed redeployment would build this strength to 5 armored divisions, 1 airborne division, 1 cavalry division, 29 infantry divisions, and 125 air groups (plus 17 squadrons). The total forces of the Pacific area would be increased from approximately 1,400,000 army troops as of 30 June 1945, to 2,439,400 as of 31 December 1945.87

Securing qualified replacements was a task that had required careful planning and close co-ordination with the War Department. The situation had become particularly difficult for the Southwest Pacific Area in February 1945 . Many units were understrength and there were cases where combat casualties and battle fatigue had whittled rifle companies down to only thirty men. The effective combat strength of the theater had been so reduced that General MacArthur had even considered inactivating a division and using its personnel as replacements.

The situation was relieved considerably in the spring of 1945. The reorganization of the Army command in the Pacific and the approaching end of the war in Europe permitted an increased flow of replacements. In May, the understrength was reduced to 4,971 by the arrival of 46,420 new men. At the end of the following month, the theater had gained 23,029 overstrength.

In the first part of August 1945, 115,000 troops passed through the Panama Canal on their way from Europe to Pacific assignments. The advance echelon of the First Army's Headquarters had arrived in the Philippines on 7 August. The VII and XVIII Corps were scheduled to arrive by 15 October and six infantry divisions were slated to arrive in the Philippines during September, October, and November.88 The tremendous forces and supplies necessary to execute the greatest amphibious invasion in history were being moved rapidly into position.

[394]

Go to: |

|

|

Last updated 20 June 2006

|