CHAPTER XV

The Race Across France

"The time you saw the American Army on the move was after Avranches," wrote an observer. After the capture of Avranches on 31 July 1944, bulldozers and scrapers were clearing the roads of the German wreckage left in the wake of the great sweep of Allied bombers and strafers. The main roads were almost bumper to bumper with vehicles. There were long trains of 2½-ton trucks, sometimes forty or fifty in a train; tank transporters with huge cabs; refrigerator trucks like boxcars; trucks piled high with telegraph poles or little nests of boats, stacked like saucers, for river crossings. There were generals' caravans and service units' mobile workshops. Between the supply convoys, batteries of artillery squeezed themselves, and sometimes there was a tank on its own treads, though more often the tanks took the side roads or made their own roads across the fields to keep from blocking the march. In and out among the big vehicles scurried the jeeps, climbing the sides of the roads to get through.1

On the run, Colonel Nixon took over the Ordnance units supporting VIII Corps, which was by then already headed for Brest. The story of the 665th Ammunition Company shows how fast things were moving. For the breakout after COBRA, one officer and 25 men of the 665th (they called themselves the Secret 25) had been selected by Medaris to operate a rolling ASP on ten tank transporters, each loaded with fifty tons of ammunition, to follow the armored columns and make issues directly from the transporters. This plan was abandoned because of the quick success of the breakout and the small amount of ammunition expended; but the company marched close on the heels of the 4th and 6th Armored Divisions, and was so far ahead of the mine sweeping Engineers that on 29 July the men had to drive cattle through their ASP site at Muneville to clear it of mines. Here they set up another rolling ASP on 198 Quartermaster trucks and continued south at a fast clip. At the one bridge leading into Avranches they ran into heavy German bombing. Two men, Technician 5 Robert H. Bender and Pvt. Joseph Keyes, remained all night at this dangerous spot to direct the trucks to their next ASP south of Avranches. The company arrived at its new area so early that it had to clear the site of snipers. Two days later, on 5 August, the 665th was attached to Third Army.2

Through the bottleneck at Avranches Colonel Nixon brought the bulk of his Ordnance units down from Bricquebec on 6-7 August. With only a few hours' notice, the

[262]

men threw their duffle bags into their trucks, skinned their shins jumping on tailgates, and were off on the long journey down dusty, bombed-out roads that became progressively more obstructed with the traffic of combat units and the wreckage left behind by the Germans. The historian of one depot company moving through La Haye du Puits, Coutances, and Gavray to Avranches found "each town an awful monument to hell itself. The stench of unburied bodies lying in the unmerciful summer sun was overpowering at times, as the convoy rolled slowly on through a red clay dust which clung savagely to the skin and blinded the eyes." To avoid the jam of military traffic, one Ordnance battalion took a back road not on any map; others moved by edging into traffic with about seven vehicles at a time; and some had to wait in line by the hour to cross bridges or intersections.3

The Ordnance men arrived at Avranches in the middle of the severest air bombardment Third Army had ever received. The Germans, counterattacking at Mortain in an attempt to drive a wedge between First and Third Armies, not only bombed and strafed the bridge at Avranches but plastered the neighborhood. Near midnight on 6 August, just after the 573d Ammunition Company arrived at Depot 1 in an apple orchard near Folligny, the Luftwaffe came over and destroyed about a thousand tons of ammunition. Explosions rocked the area for days. Ordnance depot and maintenance companies moving through Avranches down to the Forêt de Fougeres in Brittany passed through St. Hilaire-du-Harcouet while it was still burning and were bombed and strafed on the road. The 344th Depot Company had nine men killed and eighteen wounded.4

Having assembled his rear group—his heavy maintenance companies and main army depots—under the trees at Fougeres, Nixon's first effort was to bring down more supplies from Normandy. His units in the Bricquebec area, with little stock on 1 August other than the organic replacement items they carried, spare parts and ammunition, had been able to draw on the ADSEC depots in the Cotentin to some extent. Bringing additional supplies down through the Avranches bottleneck was not easy. Ammunition was brought forward on what became virtually a day-to-day basis, and in emergencies tank transporters and the trucks of maintenance units were used.5

After Avranches, Nixon faced a logistician's nightmare—the support of an army that was split into two segments, traveling very fast in opposite directions. The VIII Corps was headed west through Brittany, the XV Corps was headed east toward the Seine. By the time Nixon had got his three heavy depot companies down to Fougeres on 8 August, more than 200 miles separated VIII Corps' 6th Armored Division, which was at the gates of Brest, and XV Corps' four divisions (90th and 79th Infan-

[263]

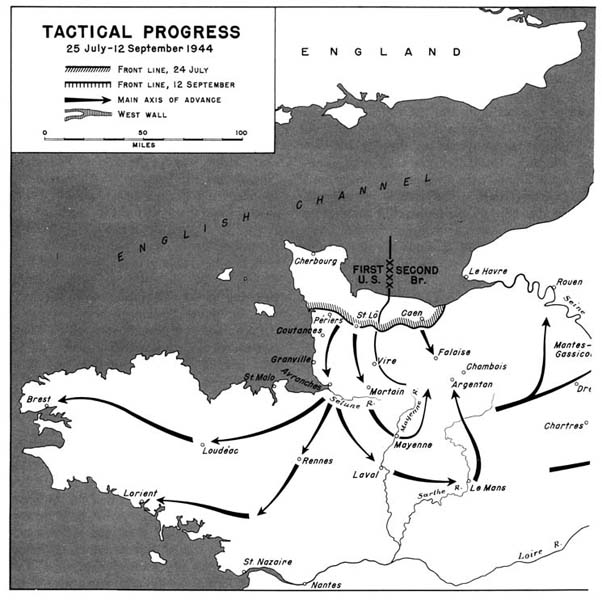

MAP 7

try, 5th Armored and 2d French Armored) at Le Mans. By that time the newly organized XX Corps' one infantry division was advancing south to the Loire. With Nixon's main source of supply eighty miles north in Normandy, his line of communications began to look like an inverted, distorted T. His solution to his problem was to hold the

[264]

main stock of supplies at pivotal points so that even if it became necessary to operate daily convoys west and south, the bulk of the supplies was never moved far from the road east, the road that the supplies would eventually follow when the main part of the army advanced toward the Seine. This axis of advance had been explained to

[265]

Nixon by Patton when they were still in England, about a week before they embarked for Normandy.6 (Map 7)

The VIII Corps was fighting in the west for the Brittany ports, with elements of the 6th Armored Division near Brest, the 4th Armored Division approaching Lorient on the southern coast, and a reinforced infantry division attacking St. Malo on the north. The VIII Corps mission lessened in importance as Third Army drove east. Even if the Breton ports were usable after being pounded by American air and artillery and wrecked by the Germans, they would still be so far to the west that they would place an intolerable burden on transportation. But Eisenhower and Bradley were unwilling to write off the ports and the attack continued, though it became more or less a subsidiary operation with low priority. The VIII Corps began to feet like an orphan.

Most of the Germans were contained in the ports, but there were pockets of resistance throughout the peninsula, stragglers and snipers who roamed the countryside like brigands, concealing themselves in the woods and hedgerows. Supply convoys had to have armed escorts; to some Americans the supply trucks racing along in clouds of dust were reminiscent of stagecoaches making a run through Indian country. Everyone had to know how to fight. Eleven Ordnance men of the 531st Heavy Maintenance Company (Tank) on the way to Brest to deliver tanks and combat cars were ambushed by the enemy at Pontlion. Pursuing the Germans into the woods, they bagged 3 German officers and 99 enlisted men, and released a captured Air Forces captain.7

The Ordnance officer of VIII Corps, Lt. Col. John S. Walker, had been warned that the forces in Brittany could not expect much in the way of supplies. No more tanks, either light or medium, or tank tracks were to be forthcoming from Third Army. An appeal to Third Army for ten jeeps and trailers met with no encouragement. Walker was told that the divisions would be refitted at the end of the peninsular campaign, and he got the impression that Nixon thought the campaign would not last long. In the meantime, the corps would have to get along with what it had. Once in a while the men of the 24th Ordnance Battalion supporting the corps were able to pick up some German supplies. The 300th Antiaircraft Maintenance Company, for example, got some badly needed electrical equipment from an abandoned German broadcasting station near Brest, braving mortar fire to enter the building. This find was a matter of luck. The captured German depots were generally disappointing.8

Soon Walker's greatest cause for concern was a shortage of ammunition. The attack on St. Malo beginning 6 August had been unexpectedly costly. The Germans were dug in behind the thick walls of an ancient

[266]

citadel and had not only 88-mm. guns but 210-mm. coastal guns turned around to fire inland. The attackers, with the bulk of VIII Corps heavy artillery, including two battalions of 8-inch guns and one of 240-mm. howitzers, were hampered by a shortage of artillery ammunition at the start of the 10-day siege. For several days some of the heavy pieces had to be restricted to four rounds a day. By mid-August, when St. Malo surrendered, partly as a result of direct hits by 8-inch guns, VIII Corps was convinced that even more heavy artillery and considerably more artillery ammunition, would be needed for the all-out attack on Brest.9

As the big siege weapons moved westward toward Brest, Colonel Walker and Col. Gainer B. Jones, the corps G-4, drove to Third Army headquarters near Le Mans to submit VIII Corps ammunition estimates— an initial stockage of 8,700 tons, plus maintenance requirements totaling 11,600 tons for the first three days. Colonel Nixon felt that Walker's demands were excessive and if satisfied would jeopardize support of Patton's advance to the east. He informed Colonel Jones that VIII Corps was basing its figures on more troops than it would have for the operation. Walker inferred that Third Army intended to reduce the attacking force because it had calculated that Brest would surrender about 1 September, after only a show of force. In the end, Nixon allotted VIII Corps only 5,000 tons of ammunition.10

The VIII Corps commander, Maj. Gen. Troy H. Middleton, "raised all manner of hell," sending an urgent request personally to 12th Army Group and finally going straight to General Bradley, who with General Patton made a flying visit to Middleton's headquarters and agreed that the newly opened Brittany Base Section would take over the supply of VIII Corps, which would be authorized to deal directly with COMZ without going through army. This did not help matters much, for there was still the problem of poor transportation, complicated by the gasoline shortage; inadequate communications; and, toward the end, little enthusiasm for the operation on the part of COMZ planners, who regarded the costly siege of Brest as wasteful and unnecessary after the capture of Antwerp and Le Havre on 4 and 12 September, respectively. It took repeated and vigorous action by Middleton, including refusal to resume the attack on Brest until his ammunition supply was assured, to get results. Ammunition supply began to improve beginning 7 September. Large shipments came by rail and also by LST's from England, which were unloaded on an emergency beach near Morlaix on the northern coast of Brittany. The ammunition company that supported the siege from a huge dump near Pleuvorn calculated that 22,500 tons were expended by the time Brest fell on 18 September. Some 11,000 tons were left over to be shipped east by rail to the German border, and in the meantime the dump was even able to fill a rush

[267]

order for 270 truckloads to support Patton's dash eastward across France.11

To the Seine and Beyond: First Army Ordnance

While Third Army was in Brittany and making its spectacular end run to Le Mans, First Army was intent on taking the important road junctions of Vire and Mortain. These junctions were needed in order to contain the bulk of the German forces, which were in First Army's sector, and provide protection for the Avranches corridor. According to the original plan First Army would then join with the British and Canadians on the north in a drive to the Seine.

The plan was changed, at General Bradley's suggestion, when the Germans launched their strong though unsuccessful counterattack at Mortain on 7 August, because it then appeared possible for the Americans and British to encircle the Germans and trap them. The upper jaw of the vise would be a line from Tinchebray east to Falaise; the lower jaw, a line from Flers east to Argentan. By closing the gap of fifteen miles or so between the two easternmost towns, the Allies hoped to trap the bulk of the German forces in France in an area that would later be known as the Argentan-Falaise pocket. Both American armies were involved. In the First Army area, a corridor curving south and east between 21 Army Group and Third Army, the plan was for XIX and VII Corps to make a converging attack in the Mortain area and then move north toward the 21 Army Group line at Flers and Argentan, respectively, and for V Corps to move southeastward from Vire to Tinchebray. In the Third Army sector, Patton's XV Corps at Le Mans was to make a 45-degree turn north and advance toward Argentan. (See Map 7.)

Getting under way on 10 August, Third Army's XV Corps, spearheaded by the 5th Armored and 2d French Armored Divisions, was in the neighborhood of Argentan on 13 August. The First Army attack started on 12 August, when the Germans withdrew from Mortain. By 15 August V Corps had Tinchebray, XIX Corps was making contact with the British several miles west of Flers, and VII Corps was in position to protect the XV Corps left near Argentan. On that day Bradley directed Patton to turn the bulk of XV Corps eastward toward the Seine, leaving the 2d French Armored and one infantry division to hold the "Argentan shoulder," aided by an infantry division from Third Army's XX Corps. Next day, 16 August, the Germans in attempting to force their way out of the Argentan-Falaise gap launched a series of strong counterattacks at the shoulder ; and though V Corps had been brought down from Tinchebray, the three First Army corps and the British were unable to prevent part of the German forces from escaping through the gap between 18 and 20 August.

[268]

Then the pursuit began—to the Seine and beyond. The XV Corps already had a bridgehead across the Seine at Mantes- Gassicourt on 20 August; on 24 August it was passed to First Army and with XIX Corps was given the mission of aiding the British to cut off the enemy on the lower Seine. First Army's V Corps was given the mission of liberating Paris. Its VII Corps bypassed Paris on the right and headed north. In the last days of August, Bradley turned First Army north to Belgium to block the German retreat, and by 2 September XIX Corps, moving infantrymen in trucks taken from artillery and antiaircraft units, was in Belgium at Tournai. That same day, the day after SHAEF became operational on the Continent, Eisenhower directed First Army to an axis between Cologne and Koblenz, pointing Third Army toward a line from Koblenz to Mannheim. South of Paris, Third Army with XX, XII, and XV Corps, the last lately returned from First Army, began its rapid dash eastward to the Moselle.

The advance across France by First and Third Armies was one of the swiftest in the history of warfare. The armies came out of the hedgerow country to the hills, then down into the plain; through pockets of German resistance and through towns that were ruined and towns untouched. History was being made each day, but "was never noticed," Ernest Hemingway reported, "only merged into a great blur of tiredness and dust, of the smell of dead cattle, the smell of earth new-broken by TNT, the grinding sound of tanks and bulldozers, the sound of automatic-rifle and machine-gun fire, the interceptive, dry tattle of German machine-pistol fire, dry as a rattler rattling; and the quick spurting tap of the German light machine guns—and always waiting for others to come up."12

At the time First Army began the movement designed to trap the Germans in the Argentan-Falaise pocket, Medaris' Ordnance Service had taken the shape that it was to retain, with few modifications, throughout the European campaigns. Behind each corps were two battalions, one a forward battalion to do third echelon maintenance and operate a collecting point, the other a support battalion that not only did fourth echelon repair and heavy tank maintenance as required, but operated a forward depot. Medaris was a firm believer then and always in the integration of supply responsibilities with maintenance responsibilities in the forward area. The battalions behind XIX and V Corps came under the 52d Ordnance Group. Normally those under VII Corps would also have come under that group, but in the action to close the Argentan-Falaise gap and in the first week or so of the pursuit they were too far away. Therefore until early September, when VII Corps arrived in the neighborhood of Paris, its Ordnance battalions were placed under the 51st Ordnance Group, whose primary mission was support of army troops—divisions in reserve, army artillery, army tank battalions, Quartermaster trucks. This was to be the pattern for the future: when distances or road conditions made it impracticable for the 52d to cover all corps areas, or when as many as four corps were fighting under First Army, the 51st Ordnance Group took on support of a corps; likewise, when necessary, 52d Ordnance Group supported army troops located in corps areas. The 72d Ordnance Group ran the main army shop and

[269]

the supply, refitting, and evacuation battalions. The 71st Ordnance Group controlled two ammunition battalions of six companies each, one battalion to operate forward ASP's, the other to run the main army ammunition depot that held army reserve ammunition and stocked the ASP's.13 (See Chart 4.)

In the very rapid advance of First Army from the St. Lô area to the western border of Germany between 1 August and 12 September 1944, First Army Ordnance troops had their first experience of blitzkrieg warfare. Medaris furnished the group commanders with excellent planning data by giving them timely information on the tactical situation and prescribing phase lines that Ordnance units had to clear at specified times in order to furnish proper support to the combat elements. After the pursuit began around 20 August, the forward Ordnance units, which had been kept highly mobile, made long jumps forward with relative ease during the good summer weather. On 22 August the command post of the 52d Ordnance Group moved 70 miles, from Beaumesnil to Les Mesles- Sur-Sarthe; two days later, 120 miles to La Loupe, where it stayed only six days before displacing forward 70 miles to the Paris area. From Paris, where the 52d took on the support of VII Corps in addition to that of V and XIX Corps, group headquarters moved on 5 September 90 miles to Laon, and on 18 September made another 90-mile jump forward that took it over the Belgian border. By that time, some of the Ordnance companies supporting the XIX and VII Corps were well into Belgium. A few days later those supporting V Corps were in the Ardennes near Bastogne.14

At the beginning of September, when elements of the 52d Ordnance Group were starting to move north of Paris, units of the 51st and 72d Groups (as well as the 71st Ammunition Group) were still near the army service area at La Loupe. But a new army supply area far to the north, at Hirson near the Belgian border, was opened on 6 September and soon these rear and army support groups were also on the move, some of the elements covering as much as 200 miles a day. The movement of the main army Ordnance depot under the 72d Group was immeasurably aided by the addition to the evacuation battalion of 64 trucks late in August, when it was decided that much of the depot stock was unsuited to hauling by tank transporters. The trucks not only moved between three and four thousand tons of depot stocks but were also extremely useful in such tasks as carrying supplies from rear to forward units and hauling ammunition.15

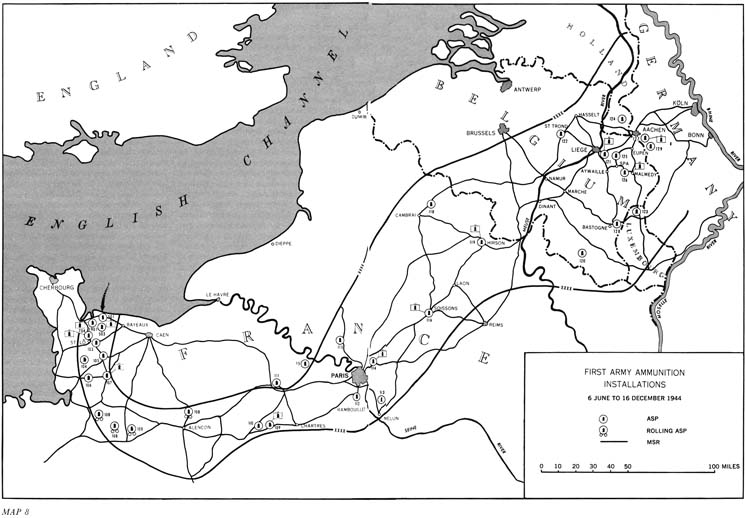

To get the ammunition forward when First Army began the swing east in mid- August 1944, Medaris organized behind the fast-moving VII Corps a mobile ASP—the only large-scale mobile ASP operated to any extent by any of the armies. For this pur-

[270]

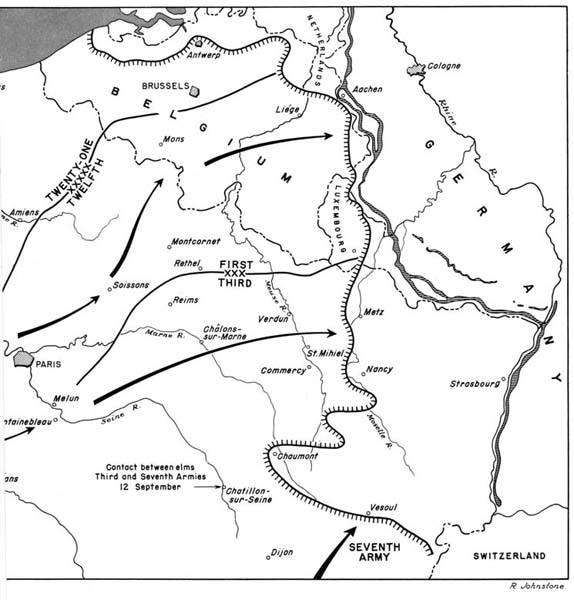

pose he arranged for the 102d Quartermaster Truck Battalion with five companies and 225 trucks to be attached to the 71st Ordnance Group. The ASP was organized in two echelons. The forward echelon, operated by the 619th Ammunition Company, issued directly to combat units from its 125 trucks, sometimes at the gun positions, and sent its empty trucks and requests for ammunition back to the rear echelon, about twenty miles to the rear. The rear echelon, operated by the 587th Ammunition Company, filled the requests of the forward echelon and sent convoys back to Depot 106, about 100 miles to the rear. Starting out from the area of St. Hilaire du Harcouet on 15 August, the ASP moved seventy miles in five days to Sees, via Corron and Lassay, and remained there until the closing of the Argentan-Falaise gap, when the eastward progress of First Army made necessary the opening of a new depot at La Loupe. In its 11-day period of operation, from 14 to 25 August 1944, the mobile ASP handled 13,156 tons of ammunition—6,615 received and 6,541 issued.16 (Map 8 )

Front and rear echelons of the mobile ASP were protected by a battery each from the 197th Antiaircraft Automatic Weapons Battalion (Self-propelled). This battalion possessed some weapons that were of particular interest to the Ordnance Section of First Army. They were the M16B halftracks with the quadruple .50-caliber (Quad-50) machine guns, improvised in England before the invasion. Sixteen had been allotted to each antiaircraft automatic weapons battalion assigned or attached to First Army. Lightly armored and clumsy though they were, the M16B's had distinguished themselves in the beachhead phase, not only in antiaircraft defense but as assault weapons in support of infantry. Beyond the Seine, as the skies began to clear of German planes, they were frequently used in a ground role and were notably effective later on at Aachen. The 197th Antiaircraft Automatic Weapons Battalion, after its support of the mobile ASP and a short stay at Le Bourget Airport outside of Paris, was attached to the 71st Ordnance Group on 5 September and continued the protection of ASP's established beyond the Seine.17

The new ammunition depot at La Loupe was hardly in operation before the stocks had to be moved forward, first to Hirson and then to Liège, in Belgium. This movement required nearly a thousand trucks. Quartermaster battalions fell far short of this number and had to be helped by trucks taken from heavy artillery and antiaircraft units temporarily immobilized behind the Seine. For the lift from the Seine to Hirson, army Ordnance vehicles of all types were used. The 71st Ammunition Group, though inexperienced in large-scale trucking, managed to establish an army ammunition depot near Liège by 11 September. Shipments began to come in almost immediately by rail: for the first time since

[271]

MAP 8

[272-273]

D-day First Army had a good railhead close to the front.18

During the period of breakout and pur- Suit in late August and early September, there were times when front and rear Ordnance units were 200 miles apart, and at one time during the fast advance through northern France and Belgium, the distance increased to 375 miles. The link that held these units together was the radio net that Medaris had planned and prepared for back in England. He had kept it in operation during June and July mainly for training purposes, since it had not been really needed in the beachhead phase. Now it came into its own, saving hours, sometimes days, in the transmittal of requests and the delivery of critical supplies to far-flung combat units and performing invaluable services in many ways; for example, ammunition men on the march could be directed to establish new ASP's as far forward as possible. Above all, the radio net provided firm control of all types of supplies. Medaris and his staff knew at all times what was on hand, where it was, and what was needed.19

In attempting to get the supplies forward in the period of fast pursuit, First Army Ordnance men had a taste of battle more than once. A maintenance unit delivering half-tracks to the combat forces on the road to Paris ran into a German column and lost fifteen men; another, on 29 August near Chartres, captured 48 Germans. The men following closely behind XIX Corps on its rapid march north to Tournai risked even more encounters, for they were cutting across one of the main routes of the German retreat. On 2 September two officers who were making a reconnaissance for an ASP, Capt. Allan H. Reed of the 100th Ammunition Battalion headquarters and Maj. Jack C. Heist, XIX Corps ammunition officer, were ambushed by German troops near Thiant and both were killed, along with the driver of their jeep, Technician 4 Zan D. Hassin.20

Next day, while Colonel Medaris was sitting in his office in a partially wrecked building outside Charleroi in Belgium, reading the depressing report on the death of the ammunition men and their jeep driver, he himself had a narrow escape. Suddenly the windows were rattled by a violent explosion, followed by a deep rumble that sounded like thunder, though the day was warm and sunny. One of the Germans' new giant rockets, the V-2, had passed over the house and buried itself in a ravine nearby. Against the earlier V-1 —the buzz bomb—antiaircraft guns gave some degree of protection, but against this monster, carrying a ton of high explosives in its nose, there was no defense. Medaris reflected that the missile was probably not aimed at First Army headquarters. Intelligence reports had indicated that the Germans intended to use the V-2 against cities, and Medaris concluded that it had simply fallen short of its target. But he now had

[274]

firsthand evidence that the V—2 was at last operational. After examining the shattered fragments of the rocket in the ravine, he instructed his technical intelligence officer to inform technical intelligence teams in the forward area, and combat troops as well, of the discovery, and to alert them to be on the look-out for V-2 "hardware." Medaris then turned his attention to the more urgent problem of supplying ammunition to the advancing forces.21

The ammunition men were doing their best to keep up in the race. A day or so after the V-2 incident, a party of about fifty men of the 57th Ammunition Company, commanded by Capt. Jack Carstaphen, routed 47 members of the 22d Grenadier SS Regiment from some barricaded farmhouses on the outskirts of Driancourt. With the loss of one man, Pvt. Allen Johnson, killed by a direct grenade hit, and one wounded, they killed 35 Germans and captured the rest. Such an encounter, a small scale replica of the unexpected VII Corps battle at the Mons pocket, was more or less accidental. The real resistance on the First Army front would come later, at the Siegfried Line.22

Third Army Ordnance in the Dash to the Moselle

While XV Corps was crossing the Seine at Mantes and passing to First Army, General Patton's two corps to the south, the XX and newly formed XII Corps, were bypassing Paris. Having cleared the south flank along the Loire, the XX Corps with the 7th Armored and 5th Infantry Divisions turned north and liberated Chartres on 18 August; crossed the Seine and liberated Reims on 30 August; and by 1 September was across the Meuse at Verdun. The XII Corps, with the 4th Armored and 35th Infantry Divisions, left Le Mans on 15 August and was in Orléans the next evening; after a short halt to protect the southern flank and wait for supplies to come up, it was on its way again. Advancing abreast of XX Corps to the south, XII Corps had three bridgeheads over the Meuse by 1 September. (See Map 7.)

This Third Army sweep across France was faster than any of the planners had anticipated. No sooner had Nixon drawn a line beyond which his 69th Group would operate—furnishing Ordnance service to all troops passing through the forward area, providing roadside repair patrols to keep the roads clear of wrecks, helping corps to set up collecting points for damaged matériel would have to be moved eastward again. Nixon himself, visiting corps to straighten out administrative tangles in his forward battalions or dashing back to Laval to 12th Army Group to get help on supply, was on the road most of the time. Because of the long supply lines and very fluid situation, the combat troops had been authorized to carry ammunition in excess of their basic loads, using Quartermaster trucks, for it was extremely hard for the ammunition trains to catch up. Sometimes ammunition convoys were diverted to points as much as 20 miles beyond their original destinations and when they arrived at a new area they would have to wait while it was cleared of enemy troops. Often the

[275]

first stocks for an ASP would remain on wheels for three or four days.23

The 573d Ammunition Company supporting XX Corps operated a rolling ASP of about 500 tons from 28 August to 2 September, issuing from its trucks direct to using units. Crossing the Marne at Fontainebleau on 30 August the company "rolled," according to its historian, "into the Wine incident." Near La Neuville the men saw a soldier coming out of a large cave carrying a case of wine. Jumping out of the trucks, they raided the cave (over the halfhearted protests of their lieutenant) and loaded up. "Then the 'Rolling ASP' rolled on. Half of the wine was given away to the French people and other 'GI's' along the highway but there was enough left in the Company for four 6x6 trucks to haul." After "a wineful night" at La Neuville, the company went on 200 miles to set up an ASP near a World War I cemetery at Dombasle-en-Argonne, five miles behind a hot fight at Verdun. A squadron of German fighter planes roared in on the tail of the convoy but did no damage. The ASP was soon set up with the help of a hundred truckloads of ammunition from a big depot just established at Nemours, in the forest south of Fontainebleau.24

The forward maintenance battalions behind XX and XII Corps had the problems that had arisen in the earlier experience behind XV Corps at Argentan. The battalion commanders had to move their companies so fast that there was not time to clear each movement with the commander of the 69th Ordnance Group. After a conference on 31 August with the commander of the 185th Battalion behind XII Corps, the group commander, and the corps Ordnance officer, Nixon decided that army would establish the general direction of the movement and the battalion commander would disperse the companies forward on the request of the corps Ordnance officer.25

It was hard to keep the intermediate battalions close enough behind the forward battalions to be of much help, especially since Nixon (unlike Medaris) had no radio net to enable the group commander to keep in close touch with his far-flung forces. One intermediate antiaircraft maintenance company, the 305th, spent the last week of August bivouacked on a steep hill near Pinthiviers, accessible only by roads too primitive to take heavy equipment. No work came in. An object of great curiosity to the French farmers, who came in droves every day to stare at them, the men spent their time swimming in a stream nearby, "card playing, and cooking as we had by this time started to trade for eggs and potatoes and the odor of French fries hung over the area at all times." The idyll was over on 31 August, when the company was dispatched across the Seine a hundred miles to Sommesous. Some of the heavy maintenance companies in the intermediate battalions were not sent forward but were transferred to the Third Army rear echelon group to help in the vehicle shops.26

By the end of August Nixon had brought his rear group—his heavy shops and main

[276]

GENERAL PATTON AND COLONEL NIXON

army depots—more than a hundred miles forward, from Le Mans to the forest south of Fontainebleau. The group had gained considerable experience in a 10-day stay at Le Mans, where for the first time the men had encountered vehicles damaged by use rather than enemy action. At Nixon's direction they had set up a control point, to which all material meant for repair, exchange, and salvage was taken and then assigned to maintenance companies, so that the flow of work was regulated and controlled. This experience was invaluable when they got to Fontainebleau, for there, as one battalion commander later remembered, "the maintenance job really began to bloom." Into the control point a steady stream of wreckers dragged enormous quantities of tanks, trucks, and weapons damaged by enemy guns and mines and by hard wear in the fast pursuit. To do the big repair job the mechanics cannibalized to the utmost, for Third Army still lacked its basic load of spare parts. The unexpectedly heavy demand for tracks on light tanks, tires for the tank transporters, parts for artillery, and motors for medium tanks could not be met at all, and awaited more support from the rear.27

[277]

The rapid advance of the Third Army had stretched the line of communications from about 50 miles on 1 August to more than 400 miles by 1 September. COMZ, with headquarters at Valognes on the Cotentin peninsula until the move to Paris in mid-September, had been able to get only three base sections opened: Normandy Base Section in the Cherbourg area; Brittany Base Section in the rear of VIII Corps; and Seine Base Section in Paris, which was concerned mainly with the administration of civil relief and the supply of COMZ installations in the city. The first week in September two base sections that might have been more immediately useful to Third Army were activated (in addition to Channel Base Section in the Le Havre—Rouen area)—Oise at Fontainebleau and Loire at Orléans, but in this early period they had all they could do to support their own units. The bulk of supplies still lay in the Cherbourg and beach areas; the railways that might have carried them eastward to the Seine had been pretty well knocked out by American bombers.

The fast Red Ball truck operation inaugurated by Brig. Gen. Ewart G. Plank of ADSEC with the remark, "Let it never be said that ADSEC stopped Patton when the Germans couldn't,"28 brought 89,000 tons of supplies from beaches to army dumps in the Chartres-La Loupe-Dreux triangle between 25 August and 5 September but most of this cargo consisted of rations, gasoline, and ammunition.29 For spare parts and other maintenance needs, the forward Ordnance depots had to depend on the cargo space in replacement vehicles. New trucks and jeeps were loaded with spare parts at the beaches and driven to Fontainebleau by men from replacement companies sent to Third Army from England. Replacement tanks, hauled by tank transporters in order to conserve tracks, arrived with spare tracks wrapped around them. ADSEC helped when it could, but for a great many of his supplies Nixon had to send Third Army trucks and tank transporters all the way back to Cherbourg. The journey of three days or more over congested roads was made even harder by the gasoline shortage. The trucks of the main armament depot company had to travel 250 miles back to the beach in order to get gasoline to haul weapons from Cherbourg.30 About this time General Patton heard a rumor which he "officially . . . hoped was not true" that his Ordnance men were passing themselves off as members of First Army in order to draw gasoline from First Army dumps. He commented, "To reverse the statement made about the Light Brigade, this is not war but it is magnificent."31

After a halt of five days because of the gas shortage in early September, Patton's army continued its advance toward the Saar. It was stopped at the Moselle on 25 September by Eisenhower's decision to immobilize Third Army in order to throw all

[278]

550TH HEAVY MAINTENANCE COMPANY, VERDUN

support to the drive to the Ruhr in the north by the British and the First U.S. Army. When Patton's advance was stopped, XII Corps had crossed the Moselle at Nancy and established a bridgehead beyond. The XV Corps, which had by then returned to Third Army from First Army and was protecting the southern flank, was beyond the river at Charmes and was abreast of XII Corps in the neighborhood of Luneville. On the northern part of Third Army's front, XX Corps had a bridgehead at Arnaville, but had been unable to take the heavily fortified city of Metz. Thereafter, restricted to limited objective attacks, the army could do little until November, when the offensive was resumed. Across the Lorraine border in Germany, Patton was slowed down by the Siegfried Line and by the increasing shortages in men, ammunition, and tanks.32

By mid-September Nixon's rear group was on the move again, from Fontainebleau to the Moselle, some 225 miles east, where Third Army was besieging Metz in an area that was studded with place names recalling World War I—Verdun, St. Mihiel, the Argonne. Nixon did not move all the companies forward at once, but with the help of ADSEC employed a leapfrogging system that he was to use ef-

[279]

fectively for the rest of the campaign in Europe. He sent a maintenance company of his rear group into the forward area to work in each collecting point and to repair matériel, if possible, rather than subject it to further damage by evacuation. When this company moved on, it left its unfinished work to be taken over by a company from a rear control point. The second company left its unfinished work to an ADSEC maintenance company that had been assisting it at the control point.33

During the lull in operations beginning in mid-September, Nixon was able to organize a group for ammunition supply, the 82d, using men from the headquarters of his 313th Battalion, which had been acting as a group until that time. Another innovation in Third Army ammunition supply that took place about this time was the use of roadside storage. This strung out the ASP's, increasing the total mileage, and hampered operations in areas far forward when tactical units had to use the roads. For example, it took an armored division two whole days to pass through the ASP of one company, causing the ammunition men (according to their historian) "very much grief and sorrow," but roadside storage took the dumps out of fields that were every day becoming deeper and deeper in mud.34

The fine weather that had made Fontainebleau so attractive (along with the first post exchange issue, first mail, and, for most of the men, a day's visit to Paris) continued only a week or so in Lorraine. Toward the end of September the autumn rains began. The men were operating their shops and dumps in the open, for Patton had never permitted them to use garages or other shelters in towns, fearing that they would lose their mobility, but French mud, as much a reminder of World War I as the trenches that still gashed the fields, soon made work all but impossible. Trucks had to be winched out of it and jacks sank. Rain filled foxholes and soaked clothing. Men's fingers were numb with cold. By October the decision to stay in the open had to be rescinded. There was a scramble for shelter in the towns, all units competing for factories, garages, stables, and the French barracks or caserns that were numerous in this fortress region. The forward battalions found buildings around Pont-à-Mousson and the rear were divided among St. Mihiel, Commercy, Toul, Neufchâteau, and Nancy. Many of the buildings were in bad shape, without roofs or windows, between German demolitions and U.S. bomber attacks, but the Ordnance mechanics knew how to repair the damage, and even manufactured stoves as winter came on. After the Ardennes breakthrough in December, units moved on to Luxembourg, but some of the rear companies went into even better accommodations at Metz and stayed until spring.35

[280]

INSPECTING DUCKBILL EXTENSIONS ON TANK TRACKS

During the fall of 1944, working within sound of the big guns blasting away on the Third Army front between Metz and Verdun, the Ordnance men tried to repair the damage done in the race across France and to get Patton's army ready for the next offensive. To give the tanks better flotation in the mud, they widened tracks by welding to the end connectors four-inch-square metal cleats called duckbills or duckfeet. Back in Paris, Communications Zone had contracted with French plants to do the job, but the effort required to send the end connectors (there were 164 on each medium tank track) to the factories made it simpler for Third Army to do a great deal of the work in its own shops, obtaining the metal cleats from local manufacturers. Much needed help with tank engines came from the Gnome- Rhône works in Paris, which by October was well into production on engine overhaul, thanks to an early September contract with First Army. This contract was later taken over by Communications Zone. Increasing COMZ support, the opening of ADSEC shops in Verdun, better rail service from the ports, and cannibalization and the conversion of captured German weapons made it possible for Third Army to

[281]

make up most of its losses in tanks and weapons by December.36

Trucks were another matter. The story of the automotive maintenance men continued to be a story of "sweat and grease, of engines and axles, of wrecks and repairs."37 Most of the wrecks came from the Quartermaster truck companies operating Red Ball and other emergency hauling projects. The heavy cost of the Red Ball operation, which had been extended until 16 November in order to move 315,225 long tons from Normandy to forward depots or to Paris for transfer to trains, was becoming all too plain. In the belief that the war would soon be over, Communications Zone had tacitly but deliberately abandoned preventive maintenance in the interest of speed and was admittedly paying "a terrific price."38

Careless drivers and reckless drivers fired by "push 'em up there" slogans had run their trucks day and night at high speeds over rough roads without giving them even the most elementary care. The trucks had been badly overloaded: the 2½-ton trucks had been made to carry six to ten tons. Overloading was ruinous to axles and hard on tires. Tires were already badly damaged from lack of care and the condition of the roads, which had become doubly hazardous from the jagged metal of C ration cans that the troops had thrown away.39

Tires for trucks and jeeps were scarce all over the world. Any real help on the problem in the ETO had to await the output of French factories that were just getting into operation as 1944 ended. No production in quantity could be expected for several months—not until bomb-damaged plants were repaired and raw materials delivered. The men in Third Army and ADSEC rounded up spares, robbed 1-ton trailers and even 37-mm. gun carriages, and did their best to save repairable tires with the meager amount of tire repair equipment they had. Until January 1945 the theater had only one tire repair company, the 158th, with enough equipment to operate. The company was split into six teams: two teams were attached to First Army, two to Third Army, and two remained with ADSEC.40

The idea of using small mobile tire repair units of one officer and 14 men (rather than companies) to go to the trucks and repair minor damage before it became major had been handed to the Ordnance Department by Quartermaster along with the responsibility for trucks in the summer of 1942. Nothing was done about it until

[282]

the fall of 1943, when experience in the Mediterranean, especially with the damage done to tires by the lava roads in Sicily, pointed the need for some change of system. Thereafter, it took a year of study, consultation, authorization, the development of electrical equipment, the preparation of a TOE, and tests, before procurement was even begun. In the meantime, the six teams of the 158th Tire Repair Company augmented their supplies with synthetic material captured from the Germans or bought locally, and improvised the extra equipment they needed. They made (according to the ADSEC Ordnance historian) "one of the most spectacular records of achievement in Ordnance Service."41

For truck and jeep parts, the Third Army Ordnance men combed collection points to obtain the most critical items— axles, transfer cases, and steering assemblies. Nixon sent searchers all the way back to Cherbourg, since as late as mid- December more than half of all Class II and IV supplies were still in Normandy and Brittany because of the priority that had been given to ammunition, food, and gasoline on the move forward. When parts were not available at all, Nixon's 79th Battalion employed French firms to make them, or made them in its own shops. The ingenuity of American mechanics was amply demonstrated in this area as in many others; for example, they made a tool for straightening bent axles and adapted British axles to American vehicles. One interesting example of ingenuity was a magnetic road sweep to be used by an Engineer construction battalion in clearing roads of the jagged metal litter so damaging to tires.42

Around Christmas, Third Army Ordnance men got some help on truck and jeep parts from a neighbor. In exchange for 40,000 duckbills, they received a quantity of brake hose and lining for trucks and distributor rotors and carburetors for jeeps from Seventh Army, which had just extended its western boundary to St. Avoid in order to support Third Army during the German counteroffensive in the Ardennes. Seventh Army, mounted in Italy and landed near Marseille in Operation DRAGOON on 15 August 1944, had come north up the Rhône Valley in an advance comparable to First and Third Armies' race across France.43

Seventh Army in Southern France

A landing in southern France—first called ANVIL, later DRAGOON—was during most of 1942 considered by American planners an integral part of the cross-Channel attack. A force mounted in the Mediterranean theater was to land in the Marseille- Toulon-Riviera area on the Normandy D-day, drawing off German divisions

[283]

from the Normandy invasion and forming a pincers with First Army. The British had never been enthusiastic about the operation, for they disliked the thought of weakening the drive in Italy, and in the early spring of 1944, after the stalemate at Anzio and Cassino, they began actively to oppose it. But the American planners, from President Roosevelt down, never wavered in their determination to make the landing in southern France. The only change they would agree to was a postponement, and this was dictated late in March by necessity. Landing craft were too scarce to permit an attack in southern France simultaneous with the cross-Channel attack.

It was argued that DRAGOON would support OVERLORD; open the large port of Marseille; and give the French army now being equipped in the Mediterranean a share in the liberation of France. These arguments did not move Churchill, who continued to oppose DRAGOON, preferring to keep the forces in Italy strong enough to go on to Istria and Trieste. Montgomery at last endorsed DRAGOON, but halfheartedly. He came later to consider it "one of the greatest strategic mistakes of the war."44

Though the trumpet, on the British side at least, gave an uncertain sound, AFHQ prepared for the battle. Planning began at Algiers on 12 January 1944 in a rambling white building on a hill overlooking the city, the Ecole Normale of Bouzareah, behind a high security fence of rusty barbed wire. The planning staff, known as Force 163, was mainly composed of officers brought from Seventh Army headquarters in Palermo, for the Seventh was to be the American army in the invasion. On this staff the Ordnance representative was Colonel Nixon. A week or so later Rear 163, a small staff of logistical planners, was established in a department store in Oran, and here the chief Ordnance planner was Lt. Col. Herbert P. Schowalter, who had been Nixon's supply officer in Palermo.45

According to plans developed for DRAGOON in the spring of 1944, three crack American infantry divisions—the 3d, 36th, and 45th—were to be brought from Italy and organized under VI Corps with General Truscott as commander. DRAGOON would also have one mixed British and U.S. airborne task force. The French, coming in after D-day, were to contribute seven divisions, under the 1st French Army.

The Seventh Army commander was Maj. Gen. Alexander M. Patch, a newcomer to the theater, but well known for his Guadalcanal campaign. He had been in command of IV Corps, then in training in the United States, and he brought with him to Africa IV Corps officers to fill the Seventh Army staff positions left vacant when Patton went to England. General Patch arrived in March. His Ordnance officer, Col. Edward W. Smith,

[284]

joined Seventh Army Ordnance at Oran in April.46

By the time Colonel Smith arrived, the Ordnance plans for the invasion of southern France were well along. They had been initiated by the Ordnance AFHQ staff in Algiers under Lt. Col. William H. Connerat, Jr., who had become acting Ordnance officer of AFHQ after Colonel Crawford's departure for the United States. His principal assistant was Crawford's executive, Lt. Col. Henry L. McGrath. Both men were thoroughly experienced. Connerat as Crawford's supply officer had been lent to Colonel Nixon for the Sicily Campaign and had made a careful study of the operations in Sicily, a study that was used in the planning for Salerno. McGrath was a veteran of three landings—Fedala, Sicily, and Salerno; in the Salerno landings he had commanded the AVALANCHE maintenance battalion.

Using Salerno as a guide, Connerat and McGrath computed basic loads and initial stocks of ammunition, major items, and spare parts, and figured troop requirements for DRAGOON. They were well aware from their own experience how important it was to get ammunition men, DUKW mechanics, and depot detachments on the beachhead as early as possible. For the move inland after the landing, they planned to support Seventh Army and 1st French Army with one ammunition battalion, the 62d, and two maintenance and supply groups—the 55th Ordnance Group for forward, third echelon work and the 54th in the rear for supply, evacuation, and fourth echelon repair. McGrath himself was to command the 55th Ordnance Group, and he hand-picked his battalions and companies from veterans of the Mediterranean campaigns. These AFHQ plans were turned over to Force 163. Nixon departed for Europe in April 1944, and the final planning, based on the AFHQ plans, was done by Colonel Schowalter in Oran. After the liberation of Rome in June, the troop list for the invasion became firm; VI Corps was moved down to Salerno for training, and in July AFHQ and Seventh Army planners went to Italy to supervise the mounting of DRAGOON from Naples.47

Airborne Ordnance Men

During the familiar flurry of preparing for another invasion, there was one new element—the training of airborne Ordnance men. In the Normandy landings, Ordnance support troops did not accompany the paratroopers but followed by sea. In DRAGOON the Ordnance men would go in by glider with the 1st Airborne Task Force, which was to be dropped behind the beach on D-day. The men selected came from the 3d Ordnance Medium Mainte-

[285]

nance Company, the second oldest Ordnance outfit, which had supported the 3d Infantry ("The Marne") Division in World War I and again in Sicily in World War II. From a detachment of two officers and sixty-nine enlisted men who were sent in mid-July to the Airborne Training Center near Rome to service pack artillery, clean and issue small arms, install wire cutters on jeeps, and mount stretcher racks on jeep hoods, an advance echelon of two officers and twenty-five men was selected to fly in with the paratroopers and support them for the first seven days, until the rear echelon could come in by sea.48

This advance echelon of twenty-five men was to be split into three seven-man teams, each team equipped with a jeep and a quarter-ton trailer loaded with 750 pounds of parts and tools. On landing, each team would join one of the three 1st Airborne Task Force combat teams. Of the four men not on the teams two were to operate ammunition points upon landing and two were to accompany Maj. Christian B. Hass, task force Ordnance officer, and 1st Lt. Max E. Clark, commanding officer of the detachment, to set up a resupply point and perform liaison. The first week in August the men of the "airborne" group were sent to Marcigliano for three days of glider training, to learn how to load their jeeps and trailers aboard the glider and lash them down so that they would not break loose during flight. After this course they were given orientation flights and, finally, one practice landing. The men's excitement over the new experience mounted when they received orders making them bona fide glider troops, entitled to flight pay. They also acquired during training a mascot that their commanding officer described as "a congenial monkey." Having "distinguished himself greatly in the knots and lashings course," the monkey was inducted into the Army and christened "Jeepo."49

Jeepo was aboard when the seven gliders carrying the Ordnance men soared aloft from Lido di Roma airfield on the afternoon of D-day, 15 August, towed by a C-47 bound for France. Each of three gliders carried a jeep and one or two of the men; four carried a trailer and six or seven men each. The four-hour flight over the blue sea was smooth and uneventful. Fifteen minutes after they passed the coast line of France, which the men recognized by the breakers far below, they spotted their landing sites, very familiar from the aerial maps they had studied during training. They were over enemy territory but luckily there was no flak, only a lurch as the tow ropes parted.

Some of the gliders were damaged in the landing; several lost a wing when they struck a tree or another grounded glider, and the one carrying two men and Jeepo lost its undercarriage and most of its nose. No one was injured, however, and after a night in a wood exposed to German machine rifle and artillery fire, the Ord-

[286]

nance teams with their jeeps and trailers joined their combat teams. They went to work at once, repairing pack howitzers, sights, small arms, jeeps, and captured vehicles and collecting plane-dropped ammunition, which they delivered under fire to the howitzer batteries. Enemy opposition was generally light, for the Germans had been surprised by the airborne landings and had been unable to bring up reserves. On 17 August the three Ordnance teams moved into a German quartermaster depot, acquired a German truck and sedan, and were able to make contact with the 3405th Ordnance Medium Automotive Maintenance Company on the beach.50

The Fast Pursuit up the Rhône

The landings on the three beaches, beginning at 0800 on 15 August, had been remarkably successful. The Ordnance planners at AFHQ considered them "textbook landings"—the best yet achieved in the Mediterranean. The timing was excellent. The German defenses were nothing like as formidable as in Normandy, the weather was fine, and the water was so shallow in most places that the waterproofing that had been applied was not needed. When Colonel McGrath arrived at the pink villa near the beach at Ste. Maxime where he had arranged to meet the VI Corps Ordnance officer, Col. Walter G. Jennings, at 0812, he found Jennings waiting with his watch in his hand. It showed that McGrath was exactly two minutes late.51

Attached to the 40th Engineer Regiment during the landings, McGrath and several members of his 55th Ordnance Group headquarters acted as observers and advisers at Ste. Maxime for a week, then moved forty-five miles inland to Brignoles to wait for the rest of the staff, who arrived with the executive officer, Lt. Col. Marshall S. David, on 27 August. By then, the forward army Ordnance companies (organized temporarily under the 45th Ordnance Battalion) supporting the three infantry divisions and VI Corps were accompanying the combat forces on their rapid march up the Rhône Valley in pursuit of the retreating German Nineteenth Army. It was 31 August before group headquarters, traveling some 178 miles in a single day, caught up with them at Crest, just northeast of Montelimar, and it was there that the 55th Ordnance Group was organized. It was composed of the 45th Ordnance Battalion with the 14th, 45th, and 46th Medium Maintenance Companies, and the 43d Battalion. The 43d, which consisted of an antiaircraft medium maintenance company, the 261st, a field army heavy maintenance company, the 87th, and a medium automotive maintenance company, the 3432d, had the task of supporting corps and army troops. Also attached to the group, but for operations only, were three French Ordnance battalions, now

[287]

advancing up the west bank of the Rhône with elements of French Army B. The French army had landed after Seventh Army and was mainly engaged in opening Toulon and Marseille.52

Like the medium maintenance companies, the army ammunition companies outstripped their controlling headquarters (the 62d Ordnance Ammunition Battalion), since they had been attached to the divisions on 20 August and had moved forward with them. This attachment was essential during the period of rapid pursuit, because the divisions carried a large supply of ammunition in addition to basic loads. By 27 August army had a sizable ASP in operation inland at Aix-en- Provence; and by 1 September the most forward ammunition company, the 66th, had succeeded in establishing an ammunition supply point as far north as Montelimar. Next day the companies were relieved from divisions and attached to the 45th Ordnance Battalion.53

At Montelimar the American forces had failed to trap the Germans, but American artillery and tanks had done considerable damage. For miles beyond, the road was lined with the shattered remnants of German tanks, trucks, guns, dead men and dead horses; and on the railroad to the north were hundreds of cars loaded with wrecked enemy weapons, including no less than six or seven railway guns like Anzio Annie—of great interest to the VI Corps veterans of Anzio. The pursuit continued, with VI Corps on the east bank of the Rhône and the French on the west trying to intercept and destroy the enemy before he could reach the Belfort Gap and withdraw to his West Wall fortifications. The generals were already planning a juncture with the U.S. Third Army around Dijon and a concerted drive east, perhaps through Strasbourg into Germany.54 (See Map 3.)

Lyon fell on 3 September and the front continued to move so rapidly that in order to keep up with the Ordnance battalions the 55th Group headquarters had to move north 68 miles on 4 September to Bourgoin, about 45 miles southeast of Lyon. By this time the simple matter of distance had placed unusual responsibilities for supply on this forward group and made necessary several unorthodox methods. For one thing, the 77th Ordnance Depot Company, the field depot which had been attached to the 43d Ordnance Battalion and was also supporting the 45th, could not get resupply readily from the two depot companies in the 54th Ordnance Group, which by 3 September was only beginning to move north from the beaches. To maintain closer supervision over the supply situation, Colonel McGrath placed the depot company under his own group headquarters. By agreement with army Ordnance, still far to the rear, he also took on the job of allocating critical major items to replace battle losses and items sent back from the front in unserviceable condition, leaving only the TOE shortage

[288]

problem for the army Ordnance Section. The new system made possible delivery of an item to the troops within twenty-four hours after the depot company received a requisition. It worked so well that it was continued even after army moved up; but it placed an additional drain on group headquarters, already too thin in officers because of an inadequate T/O. McGrath continually had to fill it out with officers from battalions and even companies.55

At Bourgoin, so far forward that one of the officers had to take time out to assist the French Maquis in the capture of two German snipers, the group not only felt the manpower pinch, but another and more painful one—the pinch of hunger. Ordnance companies were attached to corps and divisions and could draw from advance dumps, and normally Ordnance group headquarters could be attached to a company for rations; but the companies were spread out so far and were moving so rapidly that this was now impossible. Army dumps, some still on the beach, were the only resource, and in the period of fast pursuit, group headquarters had to send a truck back from 43 to 298 miles to bring up food. There were times when the men had only two K rations a day instead of the three they were allotted. Buying from the countryside was strictly prohibited.56

One other resource was discovered by a sergeant at group headquarters who was reading a copy of Stars and Stripes that arrived one day early in September. It contained the news that the Red Ball Express serving Third Army was operating on a route about 160 miles to the left of Seventh Army. Sergeant DeMartini pondered the story and then went to Colonel McGrath with a proposal that group do some "horse-trading." Though the group was poor in food, it was rich in souvenirs —helmets, pistols, rifles, dress daggers that the Germans were abandoning in their rapid retreat up the Rhône. These objects were of little interest to veterans of the Mediterranean campaigns, who already had all they wanted, but undoubtedly would interest men newly arrived in France. The sergeant proposed to load two trucks with souvenirs, take them to a Red Ball depot, and trade them for food. There was an order forbidding communication with Third Army, but Colonel McGrath, sorely tempted, consented, and the sergeant, accompanied by Capt. George B. Bennett and 1st Lt. Hueston L. J. Pinkstone of the Ordnance Technical Intelligence Team, took off with his two truckloads across the Rhône at a fast clip into the dangerous no-man's land—occupied neither by Allied nor by German forces— that lay between Seventh and Third Armies.

Three days later McGrath was awakened in the middle of the night with the news that the trucks had returned. DeMartini, smoking a cigar, pulled back the tarpaulins and displayed his trophies—huge sides of beef and mutton and whole pigs hanging from hooks; 200 boxes of cigars, and a truckload of 10-in-1 rations, candy, and cigarettes. He had got everything he wanted; and provided a story that would

[289]

be told and retold whenever group veterans got together.57

The Halt on the Upper Rhine

The official junction between Seventh and Third Armies took place on 11 September near Dijon. The DRAGOON phase in southern France was now over. On 15 September 6th Army Group, controlling Seventh Army and 1st French Army, was formed and placed under the operational control of SHAEF. At Marseille, which capitulated on 28 August, Continental Base Section had been set up and was soon to split into Delta Base Section and Continental Advance Section (CONAD)—the southern equivalent of ADSEC. But the changeover in logistical support from the Mediterranean theater to the European theater was very gradual. COMZ ETOUSA wanted control, and late in October set up a subcommand known as Southern Line of Communications (SOLOC) which became operational on 20 November. Theoretically the transfer to ETOUSA took place on that date; but pending the opening of Antwerp, the burden actually fell on COMZ MTOUSA until February 1945.

By the time the first Liberty ships berthed at Marseille on 15 September, the line of communications extended to the foothills of the Vosges Mountains, 425 to 500 miles to the north. Here, as in the OVERLORD area, railroad transportation could not be depended upon for some time because bridges and tunnels had been destroyed by Allied bombers and enemy demolitions. Therefore a tremendous strain was placed on trucks, which were needed not only for transporting supplies forward to the combat zone but for port clearance and other jobs incidental to setting up a base. In Marseille, space was found for Ordnance supplies on race tracks and exhibition grounds and excellent shop buildings in an automobile factory. Outside the city, twenty miles to the northwest at Mirimas, Ordnance officers discovered an ammunition depot that was literally made to order, with a railroad where a hundred European freightcars could be loaded at a time, permanent buildings fenced in for security, and 50,000 acres of flat, well-drained land plentifully supplied with roads. It was a depot built by the United States Army in 1918, but never used.58

To handle such huge installations, to serve the new divisions that were soon to land at Marseille, and to furnish forward support when CONAD moved north to Lyon, more Ordnance companies were needed than were available. Ammunition companies were particularly short; and CONAD was so hard pressed for depot companies that the Ordnance officer of Continental Base Section even considered requesting the 77th Ordnance Depot Company from Seventh Army. To a large extent the French, who were responsible for clearing Marseille, had been depended upon for service troops; but experience showed that the French Ordnance units, composed largely of French colonials— Senegalese, Indo-Chinese, and Goumiers— were only half as effective as their U.S. counterparts. Realizing that the southern forces were badly deficient in many types

[290]

of Ordnance units, General Sayler of ETOUSA arranged weeks ahead of the transfer to ETOUSA to send down a number of companies from 12th Army Group and ETOUSA COMZ, and to divert to Marseille several shipments from the United States.59

In the forward areas, pending the rehabilitation of the railroads, Seventh Army Ordnance Section mobilized all vehicles not in use, provided Ordnance drivers, and sent special convoys back to Marseille to pick up critical supplies. This emergency supply line, known as "The Flaming Bomb Express," used everything from jeeps to tank transporters, and was continued until 8 October, when a railhead opened in the Vesoul area. By the third week in October, rail shipments were arriving even farther north, at Epinal; but they were irregular and did not always deliver the supplies most needed. For some time to come, Ordnance trucks still had to make trips back to Marseille.60

In the Seventh Army area as well as that of Third Army local resources were thoroughly explored to keep men and supplies moving. The roads soon began to fill with strange vehicles ingeniously adapted in Ordnance shops—a German bakery van, a Paris bus, and civilian vehicles of all kinds. At Besançon one Ordnance company discovered some 300 European cars—Renaults, Fiats, and other makes—that the Germans had seized and stored in a warehouse. Many of them were little better than wrecks, but the mechanics by cannibalizing for parts were able to put about a third of them into shape. With a final coat of olive drab paint, they were soon in use as staff and command cars.61

After a lull during most of October, Seventh Army began in mid-November the offensive over the Vosges Mountains that brought it to the Rhine at Strasbourg early in December. The assault over rugged terrain in snow and mud, against German resistance that stiffened as the Allies approached the Rhine, was costly in matériel. Often trucks and jeeps had to be operated off the road over undergrowth or on roads littered with shell fragments, wire, and nails, which were ruinous to tires and tubes. There was a clamor for automotive spare parts. New divisions such as the 100th and 103d had arrived without their basic loads, and the trucks of the divisions that had fought through the Mediterranean campaigns were wearing out and needed not only parts but major assemblies and windshields. Tanks were also a source of worry, especially in the newly arrived 14th Armored Division, which had turned in its equipment in the United States and been supplied in Marseille with light tanks that the 2d French Armored had used in North Africa and Italy. One unexpected

[291]

demand was for grenade launchers needed by infantrymen for close-in fire support.62

The transfer of XV Corps (79th Infantry and 2d French Armored Divisions) from Third Army to Seventh on 29 September, the addition of the 44th Division shortly afterward, and the arrival of the 100th and 103d Infantry Divisions, 12th and 14th Armored Divisions, and elements of the 42d, 63d, and 70th Infantry Divisions before the end of 1944, placed a heavy burden on Seventh Army Ordnance Service because the new divisions seemed nearly always to arrive ahead of the Ordnance units sent to support them. Also, the changes in the tactical situation during December, requiring the movement and regrouping of shops and depots, complicated the task of support. Late in November General Eisenhower changed the direction of 6th Army Group's advance. After the capture of Strasbourg, 1st French Army was to concern itself with the liquidation of the Colmar Pocket, an area held by the Germans between Strasbourg and Mulhouse, and Seventh Army was to attack northward and assist Third Army in breaking the Siegfried Line west of the Rhine. But in mid-December, just as Seventh Army was preparing for its thrust into the Saar-Palatinate, the Germans struck in the Ardennes. Third Army had to be wheeled north to help First Army fight the Battle of the Bulge. Seventh Army, receiving Patton's right flank corps and responsibility for some twenty-five miles of the front on the Upper Rhine, went on the defensive until the big push into Germany got under way in March.63

In January 1945 an Ordnance observer from the States, Maj. William E. Renner, visited the headquarters of the 55th and 54th Ordnance Groups, then located within ten miles of each other near Sarrebourg in the Vosges, twenty-five miles forward of Seventh Army headquarters. He was impressed by their policy of "12-hour delivery"— the delivery of replacements for combat losses within twelve hours after the loss was reported. They had an excellent reputation for service. They had applied to good effect the techniques they had learned in the Mediterranean, the "Envelope System," for example, and the issuance of informative operations bulletins along the lines of those originated by Niblo. They had achieved a workable organization whereby the 54th's main mission was support of the 55th, the two groups operating close together geographically and functionally.64

They had worked under several handicaps. One was the inexperience of the Seventh Army Ordnance officer, Col. Edward W. Smith (a brigadier general before the winter was over); consequently, an unduly large share of the responsibility for Seventh Army Ordnance Service had of necessity fallen on his operations officer, Colonel Artamonoff, and the commander of his forward group, Colonel McGrath. Other handicaps were the weariness of the Ordnance men and the age of Seventh Army matériel. By February 1945 the 55th Ordnance Group had two companies

[292]

that had served thirty months overseas. Trucks, tanks, and guns brought from the Mediterranean were wearing out, and some of the ammunition was old. Major Renner noted ammunition boxes and propelling charges that had been in Iceland, England, North Africa, Sicily, and Italy "and they looked it!"65

It had been difficult to get new supplies from the United States. The "southerners" felt that the War Department considered them stepchildren, and even the men in the OVERLORD area were inclined to agree. To 12th Army Group, the 6th Army Group operations, though acknowledged to be valuable and valorous, were still a "sideshow." Priority on supplies and men went to First Army, which all through the fall and winter had held the limelight in Belgium.66

[293]

Return to the Table of Contents

Last updated 11 January 2007 |