CHAPTER XIX

From Papua to Morotai

There was now an American army in the Southwest Pacific. General MacArthur's request early in 1943 for a tactical organization higher than corps had resulted in the activation of Sixth Army under the command of Lt. Gen. Walter Krueger. The advance elements of its headquarters arrived in Brisbane by air on 7 February 1943. Among them were Krueger's Ordnance officer, Col. Philip G. Blackmore, and his Ordnance Section's automotive officer, Maj. Ray H. Brundidge, who had come over to Ordnance from the Quartermaster Corps. Five days later Blackmore's operations officer, 1st Lt. Clifton B. Nelson, and three of the Ordnance Section's fifteen enlisted men arrived at Brisbane on the second flight group and opened an office at Sixth Army's new headquarters at Camp Columbia, about ten miles west of Brisbane. The rest of Sixth Army's Ordnance Section came by sea, landing from the Klip Fontein on 17 April. Among them were two additional key officers: Capt. Joseph L. Douda, an expert on weapon and optical instrument repair; and 1st Lt. Clinton A. Waggoner, an ammunition expert.3

By the time the rear echelon arrived, Colonel Blackmore and the first group had had two months to get acquainted with the

[353]

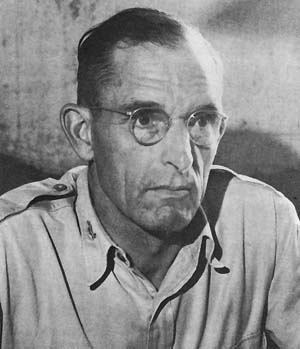

COLONEL BLACKMORE

Ordnance men in USASOS and the base sections, to find out the amount and kind of Ordnance stocks in the theater; to become familiar with the Ordnance units that were going to be assigned to Sixth Army; and to learn something about the job ahead of them. Sixth Army was small to begin with, in comparison with the armies being readied for the European campaign, but it included all the tactical U.S. Army units in the Southwest Pacific Area, and they were widely scattered. Under Sixth Army came General Eichelberger's I Corps with the two divisions that had fought in Papua, the 32d and the 41st. The 32d had been sent back to Australia and was undergoing training near Brisbane; the 41st was still in the Dobodura region in Papua getting ready for further operations in New Guinea under Australian command. The 1st Marine Division (under General Krueger's operational control) had been sent to Melbourne after the hard fighting on Guadalcanal.4 Among the smaller units under Sixth Army, some in Papua, some in Australia, were two antiaircraft brigades, a parachute infantry regiment, an infantry regiment, and a field artillery battalion. And up the coast from Brisbane in northern Queensland was a unit on which a great deal depended, the 2d Engineer Special Brigade, which was specially trained in amphibious operations.5

Amphibious landings were vital to MacArthur in the execution of his mission— Task 3 as ordered by the Joint Chiefs of Staff directive of 2 July 1942—the reduction of Rabaul, the great Japanese base in the Bismarck Archipelago. By amphibious landings, MacArthur would seize air and naval bases in the Bismarck Archipelago-eastern New Guinea—Solomons area, bases that would render Rabaul impotent. For his beach landings he needed amphibian engineers and he needed landing craft. The 2d Engineer Special Brigade arrived in Australia early in 1943 with the Southwest Pacific's first DUKW's, but getting the landing craft took longer. Because all deck space on cargo ships bound for Australia was needed for planes, the bulky LCVP's had to be shipped knocked down and it took a long time to get the assembly plant at Cairns in operation and then to accomplish training with the new craft. In May when the first detachment of amphibian engineers took off from Brisbane for Port Moresby no LCVP's were avail-

[354]

able. They took with them ten LCM's obtained from the Navy.6

The time was getting ripe for MacArthur's next move. Late in April, about a week after the Ordnance Section's rear echelon arrived at Camp Columbia, bits of information began trickling into the Ordnance office about a proposed operation to take two small islands in the Solomon Sea, Woodlark and Kiriwina, north of the southeastern tip of Papua. Troop dispositions were a regimental combat team reinforced with field and antiaircraft artillery and supporting service units, mounted for the assault on Woodlark from Townsville and on Kiriwina from Milne Bay. The Ordnance Section men assumed that it was only a command post exercise, but after two weeks of computing requirements for supply and resupply and planning Ordnance troop support, they learned that the operation was real. It was called CHRONICLE and D-day was set at 30 June 1943.

For the assault on Woodlark a 6,868-man task force composed of the 112th Cavalry reinforced by a Marine battalion and supporting units (including a U.S. Navy construction battalion to build an airstrip and roads) and appropriately designated LEATHERBACK was sent to Townsville from the South Pacific. The task force brought with it three officers and 102 enlisted men who were former members of the maintenance platoon of a South Pacific Quartermaster truck company but were now Ordnance. To this unit the Sixth Army Ordnance Section attached officers and men to handle ammunition work and repair weapons, thus creating a Provisional Ordnance Company of 5 officers and 112 enlisted men, which was to make an excellent record under the ingenious and expert leadership of Capt. Francis J. Connelly. For the assault on Kiriwina, byproduct Task Force (approximate strength 8,415), composed of the 158th Infantry reinforced with artillery units and service troops, including Army engineers to build roads and an airstrip, was assembled from various stations in the Australia—New Guinea area and concentrated at Milne Bay. For byproduct the Ordnance troop plans were almost the reverse of those for LEATHERBACK. The 158th Infantry had been intended for use primarily as an on-foot jungle scouting and patrolling unit; therefore its 35-man organic Ordnance maintenance detachment, the 4th, was designed only to repair weapons. A sizable detachment of motor maintenance men (3 officers and 72 enlisted men), as well as a 50-man ammunition detachment, had to be added, and even this relatively large force of automotive repair men was not able to overcome the handicap of miserable roads.7

After the plans for the operation were final, part of the Ordnance Section moved up to Milne Bay with a detachment of Headquarters, Sixth Army, in mid-June. The men found conditions at Milne Bay

[355]

(USASOS Base A) disheartening. In the Ordnance area at Waga Waga, muddy and full of water holes, the depot office was housed in a little thatched roof hut with a quarter wall of sago palm and a rough plank floor. Stocks of small arms, optical instruments, watches, and cleaning and preserving materials were crammed in two small canvas-covered frame structures, along with boxes of parts that had been broken open to make issues (there were no bins) or to search for parts (there were no exterior markings or packing lists). Other broken boxes were piled on dunnage, some of them covered with canvas, many open to the rain. All types of ammunition were piled together in the mud, exposed to the rain, and unrecorded beyond an estimate of the total tonnage of all types. There were very few men in the depot office, and only small detachments of maintenance, depot, and ammunition companies. To Colonel Blackmore and his staff the Ordnance situation was "very dark indeed."8

The picture was made even darker by a situation peculiar to Sixth Army. In their efforts to help mount CHRONICLE the Sixth Army Ordnance men were afflicted by a curious malady: a case of dual personality. In early May 1943, just before making his first moves against Rabaul, General MacArthur set up a U.S. task force directly under General Headquarters known as ALAMO Force (code name escalator) to conduct tactical operations in Woodlark, Kiriwina, and New Britain. Its commander was Krueger and its headquarters was virtually Sixth Army headquarters. This step removed Sixth Army from the control of Allied Land Forces, commanded by General Sir Thomas Blarney. The double role was to present Krueger and his staff with a great many perplexing difficulties. The use of three different designations (including escalator) created uncertainty and confusion; and Blackmore's men were not always sure in which capacity they were acting, whether as Sixth Army, for conducting administration and training not connected with tactical operations, or as ALAMO Force, for supporting tactical operations.9

The landings on Woodlark and Kiriwina went off on schedule 30 June 1943. There were no Japanese on the islands and the only opposition came in two small bombing attacks on Woodlark. The operation provided no real test of the Ordnance planning; for example, there was no way of knowing whether the ammunition estimates were correct because there were no expenditures except antiaircraft. But CHRONICLE was important because it was the first combat operation of ALAMO Force, and the orders from GHQ constituted standing operating procedure for subsequent landings. From the operation the Ordnance Section of Sixth Army learned two important lessons. One was the procedure for computing supply requirements. The other was a lesson that Ordnance men had learned in the Mediterranean by mid-1943 and in the European theater later: that effective supply from the rear (in this case USASOS) depended largely on the amount of personal coordination, including follow-up on the filling of requisitions and the loading of supplies,

[356]

that could be done by the Ordnance section of an army.10

The problems of furnishing good Ordnance service to the combat forces were compounded in the Southwest Pacific. In island warfare, the normal tasks of inspecting combat equipment before battle, repairing or replacing unserviceable weapons; assisting with supplies and ammunition; and seeing to it that the combat troops' supporting Ordnance units were up to standard became very complicated. Combat forces were staged on an island, in some cases two or more islands, at long, overwater distances from the army command post. Transportation, mostly by air, was uncertain and slow, for tropical rainstorms often held up flights and even when the weather was good there was always a tremendous backlog of high priority cargo and men. Officers sent out on inspection missions were sometimes absent from headquarters for considerable periods of time.11

Another drain on staff was caused by the tactics of the campaign. MacArthur's march to the Philippines involved a series of overlapping operations. Before one operation was completed, plans and preparations had to be made for the next one. While supporting the buildup of Woodlark and Kiriwina as air bases, for example, Blackmore and his staff had to make Ordnance plans for the landings on the island of New Britain, an operation which was to begin in December 1943 and was known as DEXTERITY. In the meantime the Ordnance Section had to help develop three important bases: Advance Base A, at Milne Bay (code name PEMMICAN ); Advance Subbase B at Oro Bay (code name PENUMBRA); and Advance Subbase C at Goodenough Island (code name AMOEBA). This base effort was required because General MacArthur, on a visit to Milne Bay and Oro Bay a few days before D-day for CHRONICLE,, was so disturbed by conditions at both bases that he placed Krueger in charge of developing them, and also of developing the base at Goodenough Island. In the intensive effort that followed, coordinated by Krueger's G-4, Col. Kenneth Pierce, Colonel Blackmore was one of the staff members who carried the heaviest load. Krueger gave these men credit for outstanding work.12

Milne Bay had a deep harbor that made it possible to bring Liberty ships to its docks direct from the United States; also, its sky was so often overcast that the harbor was protected to a great extent from air attack. It was encircled by mountains, but on the north shore at Ahioma there was a coastal plain a mile deep and six miles wide that provided space for shore installations and a staging area. In May of 1943 Ahioma had been selected for the main base and docks, replacing the earlier port of Gili Gili about fifteen miles west, which was thereafter used as a supply point for the Australians and the air units at the

[357]

neighboring airstrips. Along with its advantages, Milne Bay had very definite disadvantages. It rained all the time, and the mountain streams that cut through the coastal plain at many points were subject to flash floods. There was mud everywhere. Disease was rampant, even among the natives; the place had the reputation of being one of the most deadly malarial regions in the world. By March of 1943 the base surgeon had brought the rate down to 780 cases per 1,000 men (from 2,236 per 1,000 at the time of the Papua Campaign), and Krueger's surgeon was to reduce it even more; but the threat of malaria and other diseases persisted, and the steaming heat was debilitating.13 The heat, the monotony, and the creeping jungle with its hidden dangers (a soldier had been killed by a crocodile near Port Moresby) gave men, so one Ordnance officer reported, "a sort of growing horror of the place."14

Colonel Blackmore's immediate problem was to provide shelter for the Ordnance stores from the constant rain, and some form of hard flooring or dunnage for his shops, warehouses, and ammunition dumps. At times the mud was so soft and deep that bombs and heavy artillery shells were known to sink from sight.15 All of the ammunition and, in the early period, most of the Ordnance supplies were stored on the south shore at Waga Waga, which was across the bay from Ahioma and accessible only by water because miles of swamps separated it from the north shore installations. Waga Waga had a wharf that would accommodate three Liberty ships and four miles of graveled or unimproved roads. Some 5,000 tons of ammunition were stored in the area in piles of 15 to 20 tons. Before the end of July the 636th Ordnance Ammunition Company, which had arrived 15 July, had got all but about 500 tons of it on coconut log dunnage and covered as much of it as they could with tarpaulins to protect it from the rain. Some twenty natives were employed to construct rough sheds, using tree trunks as supports and tarpaulins as cover until the supply of tarpaulins ran out, and then cutting bamboo, nipa, and other native grasses to make thatched roofs. To support the coming operations, about 52,000 tons of ammunition were planned for Waga. This meant enlargement and improvement of the wharf, the storage area, and the roads, and considerably more manpower to help load and discharge vessels as well. The native force used in constructing ammunition shelters was more than tripled.16

To take care of the expansion of general supply stocks and repair work necessary in the coming operations, warehouses and shops were to be constructed in the

[358]

depot area around Ahioma on the north shore. By mid-July some prefabricated huts made in Australia were beginning to come in, but meantime shelters were built like those at Waga Waga, with thatched roofs and wide eaves. Colonel Blackmore wanted concrete floors for his repair shops and warehouses, but he usually had to be content with gravel, which was obtainable locally. Repair shops for vehicles got priority for the hardstandings because the most pressing need at Milne, as in every port and base around the world, was to keep the trucks operating, and here the climate and terrain worked against the mechanics. Mud cut out brake linings; salt water corroded parts; batteries were affected by heat and road shock; overloading and fast driving over rough roads broke springs; and carelessness about first and second echelon maintenance aggravated all these troubles and caused many more. The decision to ship crated vehicles direct to Milne in order to save time made it necessary to set up an assembly line operation. At first it was quite primitive, laid out along roads and protected only partially from the rain by canvas covers; but by November 1943 the Ordnance "Little Detroit" operation had been housed in prefabricated buildings and was turning out, working two shifts, as many as 120 vehicles a day. Combat troop labor was used to solve the manpower problem.17

Oro Bay, 160 miles by air up the New Guinea coast from Milne and 20 miles by road south of Buna, was in some respects potentially a better place for a base than Milne Bay. The terrain was more suitable and the climate was less oppressive. On the other hand, it was visited more often by Japanese bombers because it did not have Milne's habitually overcast sky. During the spring months of 1943 Oro Bay had suffered severely from Japanese bombers.18 It was also far behind Milne Bay in port development: not until August were there docks for Liberty ships. A tremendous amount of construction was necessary, such as building a road to the air base deep in the interior at Dobodura, laying secondary roads to serve the dumps and depots around the port, and building shelters for supplies. A sizable Ordnance service center was planned on 150 acres of grassland along the Eroro River, and a new and improved ammunition area near Hanau, which was to become the important Hanau Ammunition Depot.19 The immediate task was to furnish Ordnance support to the 41st Division, then engaged in the Lae-Salamaua campaign with New Guinea Force.20

Port and road conditions at Goodenough, a small mountainous island off

[359]

HEADQUARTERS OFFICE, BASE ORDNANCE, ORO BAY, 1943

the southeast coast of Papua, were very similar to those at Oro Bay. Here also was a suitable harbor—Beli Beli Bay—but dock construction for Liberty ships was not possible until August, and a tremendous amount of road building and construction work was required.21 In natural beauty, Goodenough lived up to its name and reputation of being one of the most beautiful of the western Pacific islands. To the historian of one Ordnance unit "it far surpassed expectations—rolling hills covered with alternate patches of tall rank grass and timber land . . . filled with cool, rock-filled mountain streams."22

New Weapons for Jungle Warfare

Late on the evening of 5 October 1943, about two months before the DEXTERITY operations were to begin, there arrived at Sixth Army headquarters in Brisbane a group of six experts sent out from the United States by General Marshall to find out what weapons were most needed for

[360]

jungle warfare. Col. William A. Borden of the Ordnance Department was in charge of the group, which was composed of Ordnance officers with the exception of one officer each from the Corps of Engineers and the Chemical Warfare Service. Borden brought with him in the plane several new items, the most important of which were the 4.5-inch rocket developed by Ordnance and the 4.2-inch mortar developed by the Chemical Warfare Service. These and other items were exhibited and tested at a series of demonstrations held in the Southwest and South Pacific Areas throughout October.23

Borden had high hopes of demonstrating that the 4.5-inch rocket would destroy Japanese coconut log bunkers such as those encountered at Buna. But the perverse rockets refused to perform as well as they had at the Aberdeen Proving Ground. They were erratic in flight, and were relatively ineffective. The men in the theater, who had been impressed by the performance of the lone 105-mm. howitzer at Buna, felt that the answer to the bunker was conventional artillery, especially 105-mm. and 155-mm. howitzers, and that the most pressing need was for tractors to get these pieces through jungle mud. general Krueger was very much impressed by the 4.2-inch mortar. The 4.2-inch mortar had been used to fire several types of shells, and had now been equipped by Chemical Warfare Service with a high explosive shell. The flame thrower, also a Chemical Warfare item, was well liked. Perhaps the most popular Ordnance item displayed was the rifle grenade, adapted from the 60-mm. mortar shell, affixed to the M1 rifle and used not only for firepower but for signaling. Little interest was manifested in the 4.5-inch rocket except for its possible use in barrage fire from landing craft. At a demonstration the preceding spring, Krueger had seen the 2d Engineer Special Brigade fire a 4.5-inch rocket projector mounted on a DUKW.24

In discussions with the commanders, Borden found generally that they were hesitant about introducing any new equipment for fear of increasing their supply problems, which were already serious enough, and that they were for the most part satisfied with the weapons already in the theater. They had achieved some success in the limited use of light tanks, and believed that both light and medium tanks could be used in the jungle if wider tracks were installed. Bazookas had yet to prove themselves in the Pacific, but there were plenty of them in the theater. In Africa the early models had been withdrawn from use in May 1943 because of malfunctions, and the necessary modifications had not yet been completed on all of them, but improved models continued to be produced. On the whole, SWPA felt that the most pressing need was for more weapons, immediately. General MacArthur, who was

[361]

"most appreciative of the effort being made to provide him better equipment" instructed Borden to "cut corners and red tape." Air shipment was authorized for large quantities of rifle grenades and 4.2-inch mortar materiel. Borden reported from SWPA: UA11 admit that the Buna campaign was on a shoestring, and they do not expect to operate that way."25

The Move Northward Begins With DEXTERITY

Early in August Colonel Blackmore had been called to Brisbane to coordinate with GHQ and other headquarters his plans for Ordnance support of DEXTERITY. The object of DEXTERITY was to seize Cape Gloucester on the northwestern tip of New Britain, the largest island in the Bismarck Archipelago. Establishing control over western New Britain would provide airfields for the capture or neutralization of the Japanese base at Rabaul on the northeastern tip of New Britain, and would protect the right, or Vitiaz Strait, flank of MacArthur's march up the New Guinea coast. Shortly before the main effort at Cape Gloucester, a diversionary landing was to be made on the southern coast of New Britain at a place near Gasmata that was thought to provide facilities for an emergency airfield. The Cape Gloucester Task Force, designated BACKHANDER,, was composed largely of elements of the 1st Marine Division. The Gasmata Task Force, designated LAZARETTO, consisted mainly of the 12 6th Regimental Combat Team of the 32d Division. The rest of the 32d Division became ALAMO Force reserve. In October the combat units began the movement north from Australia to their staging areas: the 1st Marine Division moved from Melbourne to Goodenough Island and the Milne Bay and Oro Bay areas and the 32d Division from Camp Cable, Queensland, to Goodenough Island and Milne Bay and both began training in jungle warfare and amphibious operations. By 21 October Milne Bay had become so congested that Krueger moved ALAMO Force headquarters to Goodenough, where it was accommodated in tents and native huts. To the dismay of the headquarters men on Goodenough, in one 24-hour period they were drenched with 27 inches of rain.26 (See Map 2.)

Plans for DEXTERITY were well advanced when GHQ discovered that the area around Gasmata was unsuitable for airfield development. The Gasmata operation was therefore canceled and LAZARETTO Task Force was dissolved. But General Krueger felt that a secondary landing on the south shore should still be made in order to divert the enemy's attention from Cape Gloucester, and Arawe was decided upon. Since only about 500 Japanese were known to be in the Arawe area, a smaller

[362]

task force composed mainly of the 112th Cavalry Regimental Combat Team and called DIRECTOR was set up for the new south shore landing. The invasion date for DIRECTOR was set at 15 December; that for BACKHANDER was 26 December.27 These dates represented a postponement of about a month from the original landing dates to allow more time for the development of Oro Bay as the major supply point for both task forces, and also to provide facilities for an advance staging area at Langemak Bay (code name REDHERRING) in the Finschhafen area, far up the coast of New Guinea and almost directly across Dampier Strait from Arawe. Finschhafen had been captured by New Guinea Force early in October.28

Cape Gloucester and Arawe

For the Sixth Army G-4 DEXTERITY planners at Good enough, the principal problems were Ordnance problems—vehicle distribution and ammunition. Everybody was clamoring for trucks and jeeps. In October a truck company and two evacuation hospitals arrived at Milne Bay without any vehicles and had to be supplied. Everybody was pressuring, especially the marines. Refusing to credit any assurance of resupply, the 1st Marine Division insisted on having everything it would need issued to it at once. The marines presented another serious "headache for Ordnance"— they possessed trucks which were not Army issue. Parts for these had to be scrounged from other Marine outfits. As for ammunition, the quantities to be distributed to the task forces were a serious problem, since experience data were lacking. And even more pressing was the problem of keeping the ammunition dry. At Nassau Bay the 41st Division had been complaining that about 65 percent of its artillery ammunition had been received in such bad shape that the powder had to be removed and dried out and other work done before it could be fired.29

These problems and many others plagued Krueger's Ordnance staff in planning for support of DEXTERITY. The operation took place at a time when the planners had also to assist in the buildup of the bases at Milne Bay and Oro Bay, and at a time when the Pacific had low priority on supplies and service troops. The planners were hampered not only by a shortage in Ordnance supplies and troops but also by uncertainty as to the amount of supplies that were actually needed. In this respect they suffered from handicaps peculiar to SWPA. There was no Ordnance officer on MacArthur's tactical staff; therefore GHQ decisions were made without the benefit of expert Ordnance advice. There were changes and delays before the troop lists were made final. In any case, consumption rates in SWPA varied widely from the normal. In this dilemma the supply experts at Sixth Army Ordnance Section devised a simple but effective system for stocking maintenance

[363]

and depot companies. They set the level of supply at thirty days and required the companies to submit requisitions every fifteen days for items required to maintain the level, computing quantities on the basis of consumption for the previous fifteen days. In putting the new system into effect, the experts had to surmount several obstacles. The first 15-day figures had to be multiplied by at least three to cover the necessary delay before a shipment could be received. Good requisition clerks were scarce. Mail service between bases was so poor that requisitions had to be delivered by officer courier. But this requisition system worked so much more satisfactorily than the "semiautomatic" system used by other supply services that the commanding officer of the U.S. Advanced Base, USASOS, was soon recommending that it be adopted by the other services.30

During 1943 the Sixth Army Ordnance Section did not have the help of a corps Ordnance staff (I Corps was not employed in combat operations until April 1944) and even lacked battalion headquarters to assist in the detailed planning for combat support. It had to make very detailed parts estimates to supply the maintenance companies. Another problem was that often Ordnance units would be pulled out of USASOS and placed under army control without sufficient time for conversion from base units to field units; and after one operation was over, would revert to USASOS until time for the next operation. The few available Ordnance units had to be torn apart and spread thin.31

The experience of the 622d Ordnance Ammunition Company was typical. Arriving at Milne Bay in mid-September (having landed in Australia from the United States only two weeks before), the company was attached to the First Provisional Ordnance Center in the Ahioma area and worked the rest of the month erecting warehouses and on other labor details. The men spent October at Waga Waga helping the 636th Ordnance Ammunition Company operate the Dingo Ammunition Depot. In November one officer and ten enlisted men were placed on detached service with the 3469th Ordnance Medium Maintenance Company to support the DIRECTOR (Arawe landing) force. The rest of the company sailed for Oro Bay to support the BACKHANDER (Cape Gloucester) force, along with the 2636. Ordnance Medium Maintenance Company.32

The DIRECTOR force staged at Goodenough (ALAMO Base 1) and used REDHERRING, in the Finschhafen area (ALAMO Base 2) as a rear base. The 112th Cavalry Regimental Combat Team and other combat elements were to proceed to Arawe from Goodenough in APD's (high-speed destroyer-transports) and go ashore on 15 December in amphibian tractors, LVT (A)'s (Buffaloes), and LVT (1)'s (Alligators), landing craft, and rubber boats. On the invasion, one officer and fifty men of the 346gth accompanied the assault forces in LCT's to handle supplies and ammunition, another officer and twelve men went in to perform maintenance; and two ser-

[364]

geants from the ammunition company went along to supervise ammunition storage.33

Aided by a bombardment at first light by seven naval destroyers and accompanied by two DUKW's firing 4.5-inch barrage rockets—the first use of such rockets in a SWPA landing—the main assault force made a successful run to the beach at Arawe in Buffaloes and Alligators and had arrived at its final objective by midafternoon. Japanese planes bombed and strafed constantly, but the only serious opposition on land was directed against a smaller force in rubber boats attempting to land before dawn in another sector. Enfilade fire from enemy machine guns and a 25-mm. dual-mounted antiaircraft gun sank twelve of the fifteen boats, and some of the men drowned while they were trying to free themselves of their equipment. A single salvo from a destroyer finally silenced the enemy guns.34

One of the first jobs for the Ordnance shore party at Arawe was to supply rifles and submachine guns to the men who had lost their weapons in the sinkings, a job that was made easier by the nearness of the base at Langemak Bay. In all sectors weapons were generally either lost or completely demolished by bomb fragments, so that little repair work came in. The maintenance party spent part of its time collecting captured Japanese weapons, but most of it in disposing of enemy bombs. There was heavy bombing and little effective defense against it, because the long-expected battery of 90-mm. antiaircraft guns did not arrive until the end of January. The Ordnance men along with the combat troops lived on C rations and slept in rat-infested trenches. On the night of Christmas Eve, one of them looked up from his trench and saw a Japanese plane dropping a red and green flare, "as though he were helping us to celebrate Christmas." There were no casualties among the Ordnance troops, "but if men can be battle scarred without drawing blood," their historian reported when the first of these troops returned to Finschhafen, "these men were good examples, completely fagged, nervous, dirty, bedraggled but with good moral [sic] and grinning, glad to get back."35

The Ordnance men supporting the BACKHANDER force—two combat teams of the 1st Marine Division—did not suffer as much as those in DIRECTOR from Japanese air attacks but had to contend with another assault from the heavens in the form of torrential downpours of rain. When the invasion forces set out from Oro Bay on LST's on the afternoon of Christmas Eve, accompanied by sizable detachments from the 263d Ordnance Medium Maintenance Company and the 622d Ordnance Ammunition Company, the weather was clear and hot; but the day after the landing on 26 December (Christmas Day across the International Date Line) the northwest monsoon struck Cape Gloucester bringing solid walls of water that lasted for hours (and were to recur every day for months) and howling winds that sent huge trees crashing down in the jungle. And when the marines got over the narrow beaches and hacked their way through the jungle, they came upon a deep and treacherous swamp for which their maps had not pre-

[365]

pared them. For this reason the Marine shore party (under which the Ordnance men worked) concentrated the dumps along the narrow strip of firmer ground just off the beaches. Supplies had to be carried forward in amphibious tractors; heavy artillery (the marines had 155-mm. guns) and Sherman tanks bogged down. But Japanese resistance was sporadic, and in the end the marines achieved a comparatively economical victory that contributed to the neutralization of Rabaul and made the coast of New Guinea safe from a Japanese land invasion across the Vitiaz Strait.36

To the men at Sixth Army Ordnance Section, the New Britain campaign was memorable for complaints from artillerymen about receiving mixed lots of artillery ammunition. This was the first Pacific campaign in which American artillery (as well as the medium tank) was used to any extent. Because the first shipments of artillery ammunition to SWPA had consisted of many lots of only a few rounds each, segregation by lot number had been as difficult there as in other theaters. Maj. Philip Dodge, the first ammunition storage expert sent out to SWPA, was able to give the artillerymen some helpful suggestions on fire adjustment; but any real alleviation of the situation had to await later shipments of larger lots.37

Saidor

The New Britain campaign had hardly begun when the attention of GHQ focused on a new landing on the coast of New Guinea, as a result of the successes of New Guinea Force at Salamaua, Lae, and Finschhafen. In mid-December ALAMO Force received a directive to add a landing at Saidor, no nautical miles up the coast from Finschhafen, to the DEXTERITY operation. For this purpose Krueger set up the MICHAELMAS Task Force, composed of the 126th Regimental Combat Team of the 32d Division (originally intended for the Gasmata landing), reinforced by artillery and antiaircraft units, Engineers, and other service units, placed it under the command of the assistant commander of the 32d Division, and gave it the job of seizing Saidor on 2 January 1944. The task force staged at Goodenough. By early morning of New Year's Day 1944 the APD's and LCI's carrying the assault forces were on their way, preceded by the slower LST's carrying heavy equipment and bulk supplies.38

[366]

Aboard one of the LCI's was the task force Ordnance officer, Capt. Argyle C. Crockett, Jr., commander of the 21st Ordnance Medium Maintenance Company, with eight men from his company and three officers to supervise ammunition operations, antiaircraft maintenance, and bomb disposal. Also aboard to assist in the initial landings was an 8-man detachment of the 59th Ordnance Ammunition Company, an experienced company with a long record of service in SWPA, which also furnished a 32-man detachment to operate an ammunition depot in the Cape Cretin area where the MICHAELMAS Force's resupply point (code name shaggy) was located. Along with the task force Ordnance staff, the assault forces were accompanied, for contact Ordnance work, by a detachment of thirty men from the 732d Ordnance Light Maintenance Company (the 32d Division's own Ordnance company) many of whom were veterans of the Papua Campaign. In several respects the Ordnance plans for Saidor differed from those for the other, smaller, DEXTERITY operations. For the first time, in recognition of the baleful effect of the tropics on fire control equipment, a small antiaircraft repair team went along. This policy was to be continued in future operations. Also, a much smaller proportion of ammunition men was allotted for the MICHAELMAS landings than for the other operations.39

Saidor differed from the other DEXTERITY operations in another respect. It dispensed with a preliminary air bombardment to insure surprise. An effective naval bombardment was provided by the destroyers, and as the first landing wave of LCV's neared the beaches there was a rocket barrage, this time by LCI's rather than DUKW's. The landings met with little opposition. For the Ordnance area, including the ammunition dump, maintenance shops, and bivouac area, the staff selected a place in dense timber between two creeks, but the access road was so poor that the ammunition had to be dumped on the beach.40

On 8 January 1944 the bulk of the 21st Ordnance Medium Maintenance Company arrived at Saidor on an LST. After preparing their bivouac area by digging foxholes and covering them with logs and slinging hammocks from trees, the men set up their shop area, bulldozing a road through it and dispersing their working sections around the perimeter. But they had hardly begun work on their first repair jobs, and the evacuation of the Japanese materiel turned in to them, when the rains began on 14 January. The roads into and out of the shop area soon became impassable as torrents of rain continued to fall. In spite of efforts to bring in gravel to put down on shop floors, vehicles and other heavy equipment bogged down and even after repairs were made could not be returned to the combat men. Parts had to be hand-carried or hauled out in trailers towed by tractors. Men sank ankle-deep or even knee-deep in mud. Little work

[367]

could be done, except repair of watches and instruments, until a new shop area was set up in mid-February on sandy, rocky soil.41

On 31 January Headquarters, ALAMO Force, moved from Goodenough Island to Cape Cretin (shaggy), where ALAMO Force Supply Point 2 was located. Here the 3469th Ordnance Medium Maintenance Company, reinforced with a 20-man detachment from a depot company, was operating the Ordnance maintenance and general supply facilities, and the 59th Ordnance Ammunition Company, using troop labor, was operating the ammunition dump. On 27 February Headquarters, Sixth Army, arrived at Cape Cretin from Brisbane. For the first time, the Ordnance Section was together and the men were spared the necessity of long trips for coordination. The ALAMO Force Ordnance staff, while continuing supervision over Ordnance operations at Kiriwina, Woodlark, Goodenough, Arawe, Cape Gloucester, and Saidor, had to plan for support of the assault on the Admiralties by Task Force BREWER, 29 February 1944, and for the first large-scale SWPA invasion, that of Hollandia, New Guinea, by RECKLESS Task Force early in April.42

Support of Brewer in the Admiralties

Capture of the Admiralty Islands, lying some 200 miles north and east of New Guinea and used during 1943 by the Japanese as staging points for aircraft flying between Rabaul and the northern New Guinea coast, would not only protect the Allied advance up the New Guinea coast, but would also provide an excellent offensive base for the march to the Philippines. Of the two main islands, the larger, Manus, was big enough for extensive shore installations and had an airdrome. There was also an airdrome at the very much smaller island of Los Negros, which was separated from Manus by a shallow, creeklike strait, and extended in a rough horseshoe curve to form Seeadler Harbor, one of the finest natural harbors in the world. The sights were set at first on the seizure of the Seeadler Harbor area, which MacArthur assigned to ALAMO Force in November 1943. On 13 February 1944, after planning was well under way, he expanded the mission to the seizure of all the Admiralties, with a target date of 1 April.43

The main combat element of BREWER was the 1st Cavalry Division, staging at Oro Bay. The division was "dismounted," having exchanged its horses for jeeps, but retained a good deal of cavalrylike esprit de corps; it was an old-fashioned square division, composed mostly of Regulars, and its regiments had proud histories of service in the Civil War and Indian wars. Reinforced with antiaircraft, artillery, and other support units, some of them furnished by the South Pacific Area, BREWER represented at this stage a huge force of more than 45,000 men. Colonel Blackmore planned to back up the division's own 27th

[368]

Ordnance Medium Maintenance Company (which he considered an outstanding company) with the 287th; to send in an entire ammunition company, the 611th; and because the early troop list included a company of medium tanks supplied by the Marine division at Cape Gloucester, he added an 11-man detachment of the 3608th Ordnance Tank Maintenance Company—the first tank maintenance detachment planned for an ALAMO operation.44

This planning for BREWER went out the window on 24 February when General MacArthur, having been informed by the Air Forces that Allied bombers flying as low as twenty feet over the Admiralties had not been fired on and had seen no signs of Japanese, ordered an immediate 1,000-man "reconnaissance in force" on Los Negros, with D-day set at 29 February. The landing was successful; but a sharp counterattack by the Japanese showed that they were on the island in considerable force. Reinforcements bringing the BREWER Force to more than 19,000 men were rushed in, and the battles, which expanded to Manus Island, continued until May. The changes in plan considerably altered the Ordnance support of the operation. In the scramble for transportation, the 287th Ordnance Medium Maintenance Company was left behind at Milne Bay. The main support of the 1st Cavalry Division came from its own organic company, the 27th, to which a 5-man detachment of the 267th Maintenance Company (AA) had been attached in January, before the 27th left Australia.45

Two contact parties of the 27th Medium Maintenance Company (each consisting of 2 officers and 24 men) landed on Los Negros with the second combat echelon on 9 March; the antiaircraft maintenance men landed next day. An 11-man detachment from the 611th Ordnance Ammunition Company had accompanied the early assault forces, but the ammunition company did not arrive until 13 March. In the meantime, ammunition had been successfully airdropped in considerable quantities to front-line troops by Quartermaster troops in B-17's, who followed the airdrop with strafing by machine guns, pinning down the Japanese long enough to allow the cavalrymen to retrieve their shells. A serious hazard to the Ordnance troops in BREWER was the presence of Japanese antipersonnel mines. Twenty minutes after one of the 27th Ordnance Medium Maintenance Company's contact parties landed at Momote Airdrome on Los Negros, an enlisted man of the party was killed by a mine and an officer was seriously wounded.46

As soon as the Admiralties operation was successful, MacArthur ordered ALAMO Force to begin planning for a jump up the

[369]

New Guinea coast to the Hollandia area in Netherlands New Guinea, some 450 miles west and north of Saidor, a move that would bypass the concentration of Japanese at Wewak. The object was to develop at Hollandia a supply point and an air base from which heavy bombers could hit the Palau Islands and Japanese air bases in western New Guinea and on Halmahera Island. There were also good anchorages in the area at Humboldt Bay, on whose shore stood the little village of Hollandia, and at Tanahmerah Bay, twenty-five miles west. Between the two bays stood the formidable Cyclops Mountains; behind the mountains in the interior was a flat plain on which the Japanese had built three airfields. The general plan of the Hollandia operation was to achieve amphibious landings simultaneously at Humboldt Bay and Tanahmerah and to strike inland in a pincers movement to seize the airfields. The GHQ instructions, 7 March 1944, also directed ALAMO Force to effect a landing at Aitape in British New Guinea, about halfway between Hollandia and Wewak. The objective there was to seize airfields and provide flank protection for the Hollandia operation against a Japanese attack from Wewak. The code name for the whole Hollandia-Aitape operation Was RECKLESS.47 (See Map 2.)

Hollandia: "A Battle of Terrain"

The Japanese by March 1944 had developed the Hollandia area into their main rear base in New Guinea. Humboldt Bay was the New Guinea terminus of their supply line from Japan via the Philippines —the place where troops and supplies were landed from freighters and transshipped by small craft and barges down the New Guinea coast. It was not expected that the enemy would give it up without a stiff fight. General Krueger planned a sizable task force (code name BEWITCH) of about 56,000 men, commanded by Lt. Gen. Robert L. Eichelberger, and consisting mainly of I Corps with the 24th Infantry Division and the 41st Infantry Division (less the 163d Regimental Combat Team, which was going to Aitape). It also included a company of medium tanks from the 1st Marine Division. RECKLESS was to be the first U.S. operation of corps proportions in the Southwest Pacific Area since the Papua Campaign. The Humboldt Bay landing was to be made by the LETTERPRESS Landing Force from the 41st Division, that at Tanahmerah Bay by the NOISELESS Landing Force of the 24th Division. D-day for both was 22 April.48

In support of the Hollandia force Eichelberger's Ordnance officer, Colonel Darby, had the 35-man headquarters of the 194th Ordnance Battalion, which had arrived in Milne Bay from the United States at the end of January 1944. These men had spent two months training at Milne Bay, assigned to USASOS, and had then been

[370]

sent to Finschhafen on 30 March to be assigned to I Corps.49 By the beginning of 1944, the very tight situation in the Southwest Pacific on Ordnance troops was beginning to ease, thanks generally to high-level decisions in Washington to furnish the Pacific more support and especially to General Somervell's recommendations after his trip to the theater in September 1943. Using recent arrivals in the theater, General MacArthur's G-3 was able to allot to RECKLESS two ammunition companies, a depot company, and two medium maintenance companies, which, with antiaircraft repair and tank detachments and the 41st and 24th Divisions organic maintenance companies, brought the Ordnance troop list for the operation up to 1,246 men, a very much larger proportion of Ordnance troops to combat troops than had been yet furnished for any SWPA operation.50

The main effort was to be made at Tanahmerah Bay, because Japanese defenses were thought to be concentrated at Humboldt Bay. The NOISELESS Landing Force, therefore, was given the heaviest weight of Ordnance troops—the headquarters of the 194th Ordnance Battalion; the 171st Ordnance Depot Company; the 410th Ordnance Medium Maintenance Company (plus two antiaircraft repair teams and one tank maintenance detachment); and the 642d Ordnance Ammunition Company— all in addition to the 24th Division's own 724th Ordnance Light Maintenance Company. The LETTERPRESS Landing Force at Humboldt Bay received the 287th Ordnance Medium Maintenance Company (plus two antiaircraft repair teams and a tank maintenance detachment) and the 649th Ordnance Ammunition Company, in addition to the 41st Division's 741st Ordnance Light Maintenance Company (minus the detachment going to Aitape). In both landings the first assault elements, on APD's or LCI's, were to carry with them as much ammunition as they could; the second elements on LST's, APA's (attack transports), or LSD's (landing ships, dock) would carry at least two units of fire; and the follow-up LST's in the assault echelons would carry enough ammunition to bring artillery, mortar, and grenade ammunition up to six units of fire, other types up to five units of fire. With regard to Class II supplies, the maintenance companies were to carry, in accordance with established ALAMO practice, 15 days of supply initially (the light maintenance companies for divisional troops, the medium maintenance for non-divisional); the depot company 30 days; resupply to both landings would be 15 days on the first available transportation and thereafter by requisition. The resupply point was Base F at Finschhafen.51

The convoy of transports, freighters, LST's, and LCI's that steamed through the Vitiaz Strait on its way to Hollandia, escorted by Navy battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and carriers, was incomparably the

[371]

largest yet to sail for a SWPA landing—so vast that it was almost unbelievable to General Eichelberger, who remembered the lean days in 1942. The Southwest Pacific seemed indeed to have broken what he had called "our lease in Poorhouse Row."52 And the cargo aboard the ships, as well as the landing plans, showed that the RECKLESS planners had taken to heart the lessons in DEXTERITY and BREWER. Aboard were 155-mm. guns because it had been demonstrated that heavy artillery was needed to penetrate the jungle and destroy bunkers; medium tanks, because they had proved better than light tanks; and heavy engineer equipment for roadbuilding, to be put ashore promptly, because experience had shown that it was useless to land trucks without first building roads. Many of the trucks aboard the LST's were loaded with supplies, ready to be driven to the dumps and then unloaded and returned to their LST's, because the technique of "mobile loading," begun in CHRONICLE, had proved its worth. Previous operations had also shown the need for ample boat and shore engineer regiments of men trained to unload bulk cargo quickly; and the necessity for prompt resupply of all items.53

After steaming north on a 300-mile detour around the Admiralties to deceive the Japanese, the ships turned south and about midnight on 21 April, the task forces separated, NOISELESS reaching Tanahmerah Bay shortly before sunrise, and LETTERPRESS reaching Humboldt Bay about the same time. When the naval bombardment lifted there was little or no reaction from the enemy to either landing; it later turned out that the few Japanese on the coast had fled to the hills, some of them leaving their breakfast tea and rice still warm in their dugouts. The enemy had been taken completely by surprise.54

The task force landing at Tanahmerah Bay was in for a most unpleasant surprise: the nature of the terrain. Firsthand information had been lacking because a scouting party sent there in a submarine in March had not returned; and aerial photography had been misleading. The photographs failed to reveal that only thirty yards behind the main landing beach, Red Beach 2, was a mangrove swamp so deep as to be utterly impassable; in spots men sank to their armpits. This was the area that had been selected for the supply dumps. When the LST's ground to the beach and began to disgorge their cargo, the narrow beach was soon jammed. Strenuous efforts by the engineers to build a corduroy exit road across the swamp were useless. The tanks and artillery, first off the LST's, sank in the soft beach sand and mud. The mobile-loaded trucks had to remain on the LST's and impeded the efforts of the engineers to hand-carry the bulk supplies from the ships. The plan had been to move weapons and supplies immediately by road from Red Beach 2 to Red Beach 1 (a beach whose coral reef made it inaccessible to all except small landing craft), where there was thought to be a road leading inland to the airfields. This plan had to be abandoned because terrain between the two beaches

[372]

was so rugged that it defeated the efforts of the engineers to build a road quickly. Some equipment, including a company of medium tanks, was transported by LCM's and LCVP's to Red Beach 1; but there the tanks remained, for the road leading inland at the little settlement of Dépapré at Red Beach 1 turned out to be only a narrow track.55

Except for small teams of mechanics from the 724th Ordnance Light Maintenance Company attached to the munitions and motor officers of the regimental combat teams, the only Ordnance men in the Tanahmerah landings were those of the 642d Ordnance Ammunition Company. The 724th was not scheduled to land until D plus 2; by that time General Eichelberger had decided to divert all future landings, as well as his command post, to the Humboldt Bay area. For the first three days the 642d performed, according to the 24th Division Ordnance officer, "miracles of strength" at Red Beach 2 in cutting ammunition out of "the mess on the beach" and shipping it to Red Beach 1. On the fourth day an officer and ten men of the company were sent up the Dépapré trail to establish an ammunition dump for the 21st Infantry Regiment's drive to the interior airfields; but they found that it was impossible for even a jeep to negotiate the narrow, winding trail. All ammunition had to be hand-carried. Giving up any thought of a dump, they simply attached themselves to the ammunition officer of the 21st Infantry and kept going. Next day the infantrymen by pushing themselves to the limits of their strength reached the airfield area and were rewarded by an airdrop of ammunition.56

For the landings at Humboldt Bay better information on terrain had been available. Of the two sandspits at the entrance to Jautefa Bay, the northernmost contained White Beaches 1 and 2, the southernmost, White Beach 3. Within Jautefa Bay was Pirn, a little settlement with a jetty, and from it a track led to the interior airfields. At Pirn was White Beach 4. Pirn was also connected with a track to the village of Hollandia, to the north of White Beach 1. Immediately north of White Beach i, between it and Hollandia, was Pancake Hill, one of the first objectives to be seized after landing because Japanese artillery emplaced there could threaten all the beaches. But the Japanese had fled. The first Ordnance maintenance men ashore, two mechanics and a supply man from the 287th Ordnance Medium Maintenance Company, attached to the 41st Division, proceeded to Pancake Hill and found a Japanese antiaircraft gun with the canvas covering still on it.57

On the beaches below, the unloading of the LST's proceeded without opposition. The 649th Ordnance Ammunition Company, attached to an engineer boat and shore regiment, landed early on the morning of D-day and worked all day and the next unloading ammunition from LST's and directing sorting and stacking. By the evening of D plus 1 the northern sandspit, on which White Beaches 1 and 2 were located, was becoming extremely congested.

[373]

It was only 100 yards deep, and all along it were piles of Japanese supplies scattered by the air bombing and naval bombardment prior to the landings, some of them still smoldering. The engineers had made slow progress on exit roads because of swampy or rugged terrain; and the congestion was made even worse by the necessity for basing antiaircraft and artillery units along the sandspit. Sometime during the day a much larger detachment of Ordnance maintenance men from the 287th Ordnance Medium Maintenance Company arrived and joined the D-day group on Pancake Hill.58

By dark on D plus 1, the ammunition men had completed their LST unloading, started the movement of ammunition to their dumps, and then retired to the foxholes they had dug on D-day in the "slots" behind the seven D-day LST's. That night, sometime between 2200 and 2300, a lone Japanese bomber came over and, guided by the smoke from the Japanese stores, dropped a bomb on a Japanese ammunition dump below Pancake Hill, starting a fire that spread to an American gasoline dump and was soon completely out of hand, creating a night of terror for the men on the beach. Among those hardest hit were the Ordnance ammunition men. Of the 30 men and 1 officer in Slot 1, nearest the Japanese dump, the officer and about 18 men were wounded, and 7 were reported missing in action. The rest of the company, after evacuating the wounded men at the risk of their own lives, returned to help fight the fire, rolling gasoline drums into the ocean, attempting to build a fire break, and trying to evacuate equipment. Technical Sergeants Erickson and Kaltenberger manned bulldozers and succeeded in pulling out 40-mm. guns and equipment until one bulldozer was hit by a falling tree and the other disabled in the swamp behind the beach.59

The fire raged for two days. Observers in the offshore LST's, some of which had been diverted from the Tanahmerah Bay landing, saw for more than a mile along the sandspit great billowing clouds of smoke and walls of flame, creating a fierce, eerie glare in which rockets, signal flares, and white phosphorus shells sprayed out in all directions. They heard the spitting crackle of small arms ammunition between the crashing, rumbling roar of barrage after barrage of artillery shells.60 Almost all of the supplies brought ashore on D-day and D plus 1 were destroyed, a loss estimated at $8,000,000; worse than that, in the opinion of the troops, was the fact that the combat men making their way over the trail inland from Pim had to get along on half rations and little ammunition until the offshore LST's could be unloaded. Of necessity, White Beach 3, the southern sand-spit, had to be used, which added fresh trouble, for this beach had a gradual slope offshore that prevented LST's from coming closer than forty yards. Men had to wade out waist-deep to help unload; vehicles leaving the ramps were stalled or drowned out and damaged by the salt water, for

[374]

only D-day vehicles had been waterproofed. When another detachment of the 287th Ordnance Medium Maintenance Company and the 741st Ordnance Light Maintenance Company arrived on White Beach 3 on 25 April, acting as a composite company, the men found that salt water rust and corrosion accounted for most of their repair work.61

Gradually the congestion on White Beach 3 lessened as the engineers managed to shuttle equipment and supplies in LCM's and LCVP's across shallow Jautefa Bay to White Beach 4. General Eichelberger came ashore on D plus 3 and set up I Corps command post at Brinkman's Plantation; next day, 26 April, the combat troops of the 41st Division met those of the 24th Division, and the airfields were secured. Much mopping up remained and much work was needed before Hollandia became a great base, but RECKLESS had succeeded. Critics pointed out the great cost in supplies, the folly of landing too much too soon in too small an area. The tanks, for example, could not be used, and aircraft gasoline had been landed in quantities immediately when it was known that it would be several days before the airfields could be opened. Yet the planners had had to take into consideration the possibility that Japanese air or naval forces would cut or interrupt the flow of supplies. One solution was to hold the LST's offshore and unload only the equipment and supplies that could be used immediately. But the LST's could not be tied up for long, because they were badly needed for resupply, or in other areas of the vast Pacific operations. About a hundred cargo ships, which could not be accommodated at the two-ship floating dock, had to remain unloaded in the harbor for several months. The value of offshore "floating warehouses," already under consideration, became more apparent.62

Aitape: the Persecution Task Force

The landing at Aitape was made on schedule on the morning of 22 April. Here as at Hollandia, the Japanese (chiefly service troops) fled after the air and naval bombardment, offering little or no opposition. The landing beach, designated Blue, was better than the beaches at Hollandia and behind it lay ample firm ground for the supply dumps. By the evening of D-day, seven LST's had been unloaded, roads were under construction, and the airfields that were the main object of the landing area were in Allied hands.63

To provide Ordnance support for the task force of about 12,000 men (mainly the 163d Regimental Combat Team of the 41st Division), the planners had allotted the entire 49th Ordnance Medium Maintenance Company; an 11-man detachment of the 629th Ordnance Ammuni-

[375]

tion Company; the usual 4-man antiaircraft repair team from the 253d Company; and about one-third of the 41st Division's light maintenance company, the 741st. The advance 20-man detachment from the 49th landed on D-day, followed on D plus 1 by a small detachment with the ammunition and antiaircraft repairmen. The repairmen lacked tools, parts, trucks, and equipment; except for their hand kits, their supplies and equipment had been bulk-loaded on an AK, the Etamin, that was only about 5 percent offloaded on D-day. The Ordnance men who came ashore on D-day soon found some captured Japanese trucks, and by cannibalizing got three of them in running condition. They managed to get their welding equipment out of the Etamin and onto one of the captured trucks, but a shortage of landing craft slowed down the unloading of the rest of their gear. On D plus 6 the unlucky Etamin was hit by a Japanese bomb and all cargo was lost. The Ordnance men were badly hampered by lack of tools and parts until the rest of the 49th Ordnance Medium Maintenance arrived on D plus 8, 30 April.64

Less than a week later the 49th Medium Maintenance and other Ordnance units were preparing to leave Aitape to participate with the 163d Regimental Combat Team in the next operation up the New Guinea coast beyond Hollandia—the seizure of the Wakde-Sarmi area, scheduled for mid-May.

Relieving the 163d Regimental Combat Team, the 32d Division was brought up from Saidor as the main combat element of persecution Task Force. Before the end of June the Aitape airfields and the west flank were secure; but on the east flank in the region of the Driniumor River about eighteen miles east of Aitape, there had been increasingly heavy clashes with Japanese patrols. MacArthur's headquarters had reliable information from radio intercepts that the Japanese at Wewak were planning an attack early in July. Reinforcements consisting of two regimental combat teams and the 43d Division were ordered to Aitape, and because more than two divisions were now involved, General Krueger sent for XI Corps headquarters, placing the task force under the XI Corps commander. Until the arrival of the 43d Division the third week in July with its organic 743d Ordnance Light Maintenance Company and supporting medium maintenance company, the 288th, plus the 611th Ordnance Ammunition Company, all Ordnance support for the 32d Division and the two combat teams was furnished by the 32d's own 732d Ordnance Light Maintenance Company, its backup medium maintenance company, the 21st, and eleven men of the 611th Ammunition Company. The first job was to lay out a bigger ammunition dump (the old dump had exploded and burned on 16 May, the day after the departure of the 629th's detachment) and unload 4,000 tons of ammunition still in the holds of ships in the harbor. This was done by using a labor force of about 300 combat troops and 40 natives to clear out the kunai grass and cut dunnage. Native labor supplied by the Australia-New Guinea Administrative Unit

[376]

force was also used by the 21st Medium Maintenance Company to build warehouses and sheds for the task force Ordnance depot, and here again the Australians helped by supplying prefabricated building material.65

Early in July, reports that a large concentration of the enemy was coming up from Wewak made it necessary to organize the Ordnance men into task force reserves; weapons were issued, and pillboxes were constructed. The counterattack never got as far as Aitape; but eastward on the Driniumor a full-scale battle developed that placed heavy demands on weapons and ammunition, especially ammunition for the 105-mm. howitzers. When the 43d Division, a South Pacific Area unit that had seen hard service in the Solomons, arrived from New Zealand, it was found that 76 percent of its weapons were unserviceable; parts had to be found and the weapons repaired. Throughout the Driniumor campaign Ordnance teams were sent to the front lines to keep the weapons operating. There was a tremendous expenditure of ammunition, estimated by XI Corps to be the largest expenditure of artillery ammunition in any campaign up to that time in the Southwest Pacific. Areas inaccessible by boat or truck were reached by an unprecedented airdrop of ammunition, estimated at 150 tons. The most important result of the battle of the Driniumor was that it destroyed several Japanese divisions that might have impeded the Allied forces in their march to the Philippines. Months before the battle ended on 25 August, other SWPA forces had made huge jumps in the advance; indeed even before Driniumor began a landing had been made at Arare, New Guinea, 275 miles north of Aitape and opposite the island of Wakde.66

The Geelvink Bay Operations: Wakde, Biak, Noemfoor

Long before the landings at Hollandia and Aitape, MacArthur had set his sights on the island of Biak, at the northern entrance of Geelvink Bay, some 325 miles northwest of Hollandia. A big coral island about 45 miles long and 20 miles wide, Biak had a flat coastal plain on which the Japanese had built three airstrips capable of development into heavy bomber bases. These were needed not only for the advance of Southwest Pacific forces to the Philippines but also for the Central Pacific's Mariana and Palau operations. The island seemed even more desirable after the discovery that weather and terrain made Hollandia's airfields unsuitable for the immediate employment of heavy bombers. The only really good bases for that purpose were still, by May 1944, far in the rear in the Admiralties and at Nadzab in eastern New Guinea.67

Wakde-Sarmi

As a preliminary to the attack on Biak, the seizure of the small island of Wakde,

[377]

about two miles off the coast of New Guinea, some 120 miles west of Hollandia, seemed essential. Wakde had a good coral-based airstrip, from which fighters could protect the Biak landing; also there was thought to be in the region between Wakde and Sarmi (a settlement about twenty-five miles west) a fairly heavy concentration of Japanese that might menace the Allied advance. A report from air reconnaissance that the Sarmi area was "fuller of Nips and supplies than a mangy dog is with fleas" prompted a change in plans from a landing near Sarmi to one in the Arare-Toem area opposite Wakde. A landing there by TORNADO Task Force, composed mainly of the experienced 163d Regimental Combat Team of the 41st Division, went off on schedule at dawn on the morning of 17 May 1944. The next step, the capture of the small island of Insoemanai, less than a third of a mile off Wakde, and the emplacement there of heavy weapons to protect the Wakde operation, was accomplished by the 2d Battalion of the 163d Regimental Combat Team without opposition. Next day a landing was made on Wakde by the 1st Battalion of the 163d and one company of the 2d Battalion. They encountered stiffer opposition than had been expected; Japanese in some force were hidden in caves or deep coconut-log bunkers; but by 20 May Wakde was secure. The heaviest fighting was to come later on the mainland.68

An Ordnance maintenance detachment of three officers and 29 enlisted men of the 4gth Ordnance Medium Maintenance Company went ashore near Arare on D-day about H plus 45. Mindful of the fiasco at Aitape, they took with them enough supplies and equipment to last five days. In addition to their wrecker they had two mobile-loaded trucks, one loaded with parts (in bins) and a number of rifles and machine guns, the other with complete welding equipment. The detachment was well rounded, consisting of one instrument repairman, two armorers, two spare parts clerks (who doubled as extra automotive mechanics and armorers), two welders, three antiaircraft and fire control mechanics, fourteen automotive mechanics, two men to assist the bomb disposal officer, and one cook. They immediately sent out teams to start vehicles that had flooded out during the landing; to tow waterlogged vehicles, using the wrecker; to assist at the antiaircraft command post; and to help unload the LST's. By noon they had also found a suitable spot about a mile west of Toem, between the artillery and infantry command posts and set up their shops under a big tarp. Next day, 18 May, during the assault on Wakde the men had a chance to display the ingenuity that was often called upon in Pacific landings. When a Sherman tank dropped into seven feet of water as it left the ramp of its LCM, they recovered it with their wrecker, hauled it to their shop, flushed all parts, and removed not only the engine but the entire wiring system, which had to be cleaned and dried. Some of the drying was done in the kitchen range; and when new parts were necessary (they had no spare parts for tanks) the mechanics made them out of tin cans, wire, and shell cases. The tank was back in operation in twenty-four hours.69

[378]

Ammunition support of the TORNADO Task Force was supplied by a 93-man detachment of the 629th Ordnance Ammunition Company. The advance echelon of three officers (including a bomb disposal officer) and forty enlisted men got ashore in the Arare-Toem area on D-day, 17 May, and set up a dump to receive the ammunition coming off the LST's. They had instructions to sort the artillery ammunition by lot number as it was unloaded (mixed lots continued to be a constant problem in the Pacific as in Europe) but found this impossible. Here, as in many landings all over the world, the drivers of the dump trucks in their hurry to get rid of their cargo and get back to the ships simply dumped it on the ground without waiting for it to be unloaded. In this process, a good deal of the artillery ammunition was so badly damaged that it could not be used. The arrival on 21 May of the 158th Regimental Combat Team, of which two battalions were to be dispatched immediately to Sarmi and supplied from the task force dump, increased ammunition problems and caused concern over a possible shortage of small arms and mortar ammunition before supplies could be unloaded from ships in the bay.70

By the time the rest of the ammunition detachment and the remainder of the 49th Medium Maintenance Company arrived a few days later, the threat of a Japanese breakthrough in the Toem area and the shortage of combat troops had made it necessary for all the Ordnance men to set up rifle and machine gun defenses around their shops and dumps. The 49th had supplemented its five machine guns at one point with a captured Japanese machine gun. Toward the end of May the Japanese did attack in the area but were repulsed; and though the threat remained and for days the Ordnance men had to work all day and stand guard at night, the heaviest fighting on the mainland took place in the Maffin Bay area to the west, toward Sarmi. The battle was to continue until well into July, after the 6th Division had been brought in. Enemy strength in the area had been badly underestimated and resistance was stubborn; the Japanese were deeply entrenched in caves and bunkers and hard to root out. This was to be even more true on Biak.71

Biak

The Biak operation, begun by the HURRICANE Task Force (41st Division less 163d Regimental Combat Team) on 27 May, only ten days after Wakde, differed in many respects from anything undertaken by the Southwest Pacific forces up to that time. The landing place was selected by a process of elimination. The island is boot-shaped, and a large part of it is covered with rain forest growing out of high coral ridges; the Japanese had built their airfields on a flat inland terrace along the sole of the boot. In that area were reasonably good beaches near the villages of Mokmer and Bosnek. Mokmer, near the main Japanese airfield, was known to be heavily defended; therefore Bosnek (to the east) was selected. At Bosnek were two possibly usable jetties. The entire southern coast of Biak is surrounded by a coral reef, which made it necessary to use

[379]

LVT's and DUKW's, carried to the reef in LST's, for the landing.

The Ordnance support for the force of nearly 21,000 men (twice as many as for Wakde) was fairly heavy: to the 41st Division's own light maintenance company, the 741st, was added the backup company, the 287th Ordnance Medium Maintenance; an entire ammunition company, the 649th; and detachments from the 253d Ordnance Maintenance Company (AA), 3608th Ordnance Heavy Maintenance Company (Tank) and 724th Ordnance Light Maintenance Company, totaling about 600 men.72

On D-day (for Biak called Z-day), the ammunition company was ashore early and by mid-morning had set up ten bays along the beach road. With the help of more than a hundred combat troops, the company managed during the afternoon to unload the LVT's and DUKW's from eight LST's. In late afternoon Japanese planes came over and bombed and strafed the beach, but the bombs were all duds and the strafing not much more effective. Another air attack early next morning caused no casualties among the ammunition men. They continued unloading until about 1030, when orders came through to rush as much 105-mm. ammunition to the combat units as possible. The 3d Battalion of the 162d Infantry, advancing along the beach road to Mokmer Drome against light opposition, had run into serious trouble west of Mokmer village. From caves in the cliffs that rose sharply up from the beach, the Japanese suddenly poured down on the men a withering fire.

As soon as the ammunition men got the order, they loaded twelve trucks and sent them forward, some of the men going along as guides and gunners on the armed vehicles. Attempts to unload on the beach road met with mortar and gunfire. The gun crews suffered heavy casualties. One driver returned with six wounded men on his truck. The next effort to get the ammunition to the beleaguered men was made by boats, which could move along the shore out of range of Japanese fire and then dart inshore at full speed. The 649th loaded nine LVT's with ammunition, using four of its own men as guides and gunners, and delivered it in this manner to the battalion, returning safely late in the evening. Next morning another attempt to deliver ammunition in LVT's and LCM's was called off when word came that the battalion was being evacuated.73

The action west of Mokmer resulted in the first tank-against-tank battle in the Southwest Pacific. On 28 May a platoon of Shermans sent forward on the coast road met some Japanese light tanks and drove them back. In this skirmish the Shermans had the aid of fire from destroyers offshore, and the damage to three of the Shermans was caused by Japanese artillery fire. The first real tank battle occurred next day, when the armor-piercing ammunition of the Shermans' 75-mm. guns destroyed the Japanese tanks, whose 37-mm. gunfire was wholly ineffective against the American tanks.74 Rooting the Japanese out of the honeycomb of caves that dominated Mokmer Drome was a difficult and costly operation, requiring considerable reinforcements. In mid-June

[380]

I Corps was brought in, and General Eichelberger assumed command of HURRICANE Task Force vice Maj. Gen. Horace H. Fuller of the 41st Division, who left the theater, being succeeded as division commander by Brig. Gen. Jens A. Doe. It was late in June before organized resistance ended, and for weeks thereafter there were threats of suicide attacks by the 4,000 Japanese that remained on the island.75

The 287th Ordnance Medium Maintenance Company suffered several casualties. The advance party of one officer and fifty enlisted men, arriving on Z plus 6 (2 June) and acting as stevedores all day to unload needed supplies from the LST's, was attacked by enemy aircraft while on its way to a bivouac area that evening, and one man was wounded. After the arrival of the rear echelon on 5 June, the bivouac area became even more dangerous, for about 75 yards behind it, a battery of 155-mm. M1 guns began firing over it toward Mokmer Drome. As the men were preparing to move out on the morning of 7 June, a muzzle burst from one of the guns killed one of the men and wounded five others. The company was not able to get its shops set up until 9 June on the beach near Warwe and when it did, the work from nondivisional units and the overflow jobs from the 741st Ordnance Light Maintenance Company poured in: trucks damaged by rough roads and water holes; DUKW's damaged by coral reefs; weapons malfunctioning from constant firing; and all problems made worse by lack of preventive maintenance. But the men of the 287th, veterans of several difficult operations, knew the value of initiative and ingenuity. They improvised parts and used Japanese equipment, reconditioning some 200 Japanese trucks and putting two Japanese lathes to good use in their shops. Remaining at Biak as USASOS troops after Base H was established there, they were for a long time in danger from small bands of scattered Japanese. In September and October they captured three Japanese in their area.76

Noemfoor

The third Geelvink Bay operation, designated TABLETENNIS, was an invasion on 2 July 1944 of Noemfoor, a small circular island about halfway between Biak and the Vogelkop Peninsula of New Guinea. The Japanese were using the island as a staging area for troops moving to reinforce Biak; they had also constructed or partially completed three airdromes on it. The capture of Noemfoor would protect Biak as well as the sea lanes to the west of Biak; it would also provide airfields from which Allied fighters and bombers could cover the advance to the Vogelkop. Seizure of the airdrome sites was the principal mission of the assault force, which was the 158th Regimental Combat Team (brought up from Wakde-Sarmi), reinforced and designated CYCLONE Task Force. Of the 5,500 service troops assigned to the 8,000-man combat element some 3,000 were to be used for airdrome construction.

Like Biak, Noemfoor is almost surrounded by coral reefs; the landing plans

[381]