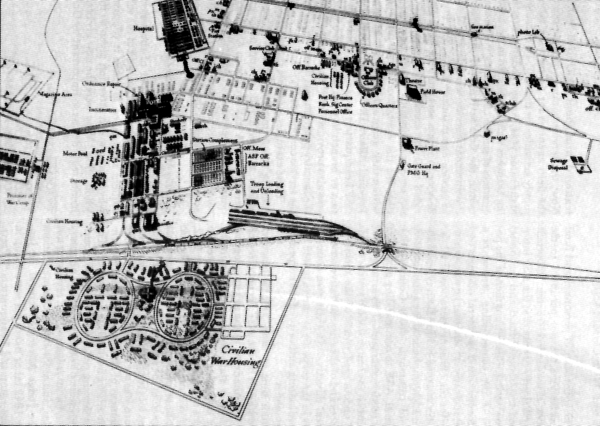

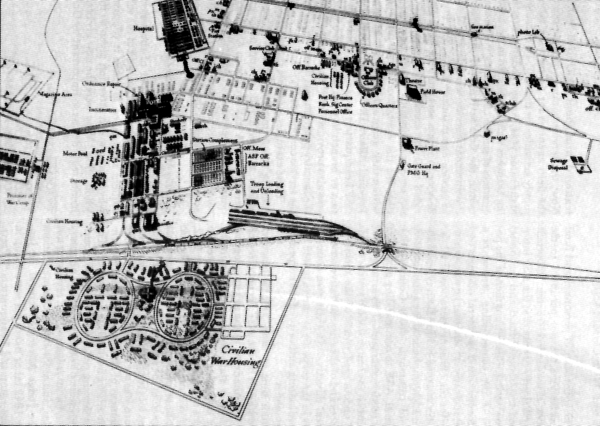

TYPICAL ASF INSTALLATIONS IN A CAMP

War Department Circular 59 of 1942 included in the list of War Department "offices and agencies" placed under the command of the ASF "all corps area commanders." There was no other reference to corps areas in the document. There was no indication of what the corps areas were to do or how they were to do it. The first ASF order on internal organization simply listed corps areas at the end of the description of the new command. The organization chart showed nine corps areas, along with the supply services and the administrative services, as "operating divisions." A footnote added: "field agents of the operating divisions on designated functions." This was the extent of the prescription of a role for the corps areas.1

The War Department history of field organization reached back to an early date. Territorial districts for the Army had first been created in 1813. In 1815 these had been renamed departments and grouped under two divisions. These territorial departments continued, with various modifications, until 1920. The amendments to the National Defense Act approved on 4 June 1920 provided for the creation of corps areas to replace the territorial departments. These corps areas were to be organized on the basis of potential military population: Originally it was intended to include in each corps area at least one division of the Regular Army, a division of the National Guard, and a division of the Organized Reserve. Each corps area had a threefold mission: tactical, training, and administrative.

The corps areas steadily diminished in importance throughout the 1920's and 1930's because of two developments. First, more and more field installations were exempted from the command of corps area commanders. This was particularly true of the field installations of the supply arms and services. Second, the corps areas were not satisfactory tactical commands. Because of curtailments in appropriations, the War Department was never able to effect the tactical organization in each corps area on the scale originally planned. Furthermore, the War Department found the fixed geographical boundaries a definite disadvantage in the training and deployment of troops. Maneuver areas available to the Army were mainly located in two of the corps areas-the Fourth and Eighth. In order to assemble large troop units for tactical training, the War Department in 1932 set up four armies embracing the nine corps areas. The final step in the separation of tactical and administrative duties in the field was taken with the creation of General Headquarters of the field forces in July 1940. Thereafter the corps areas were left with

administrative and supply duties only.2

Because of this remaining supply and administrative mission of the corps area commands, the War Department decided to include them as a part of the newly created Army Service Forces. After 9 March 1942 the commanding generals of corps areas were told unofficially to continue to function as they had in the past, pending a study of function and organization of field installations. One of the first steps taken by the Control Division of General Somervell's office was to start two field surveys as a means of throwing light on organizational problems. The second of these field surveys was conducted in New York City in April. Some members of the survey staff visited the headquarters of the Second Corps Area at Governors Island. Their investigation immediately disclosed a great amount of confusion in the headquarters regarding its duties and responsibilities. The survey staff reported: "The corps area command is not geared into the SOS operating system to the maximum possible benefit of the organization. The directives which the corps area receives are not always in harmony with those received by the district supply officers." The report on the field survey proposed that "consideration should be given to reorganization of the corps area commands as regional administrative and supervisory centers for the Services of supply."3

As a result of this recommendation, the director of the Control Division, ASF, initiated a full-scale survey of the organization and operation of corps areas. A group from the division visited the Third Corps Area headquarters in Baltimore in May and the Sixth Corps Area headquarters in Chicago in June.4 Both emphasized the same findings and both agreed there was much confusion. First, the corps area mission was confused. While tactical responsibilities had been removed, there was no clear understanding of the supply and administrative functions that remained. Second, the relations of the corps area to the many different Army installations within its geographical limits were confused. Within the Sixth Corps Area there were as many as forty-nine exempted installations. Yet the commanding general found himself called upon from time to time to render a wide variety of services to these military posts. Third, the internal organization of corps area headquarters was confused.

The two surveys recommended that all existing orders assigning duties to corps areas be replaced by a consolidated and complete statement of the mission, duties, responsibility, and authority of the corps areas and their role in the ASF organization. They recommended further that a standard organization plan applicable to all be prescribed. In addition to these general recommendations, a number of specific proposals were made for improvement in various operations being carried on by corps areas. After reviewing these proposals, General Somervell directed the Control Division to prepare a statement on the mission and to recommend an organizational plan for corps areas.

Accordingly, on 8 July 1942 the director of the Control Division transmitted a number of recommendations to the commanding general. These included a re-

definition of the mission and functions of corps areas, a standard organization pattern for corps area headquarters, and a system of classification for all War Department field installations. In addition, he proposed that these recommendations, if approved, be followed by a conference of corps area commanders at Chicago to discuss the new organization.5 The commanding general approved the proposals submitted.

The Service Command

Reorganization

The first official step in the reorganization of the corps areas occurred on 22 July 1942 when War Department orders redesignated corps areas as service commands of the ASF and provided that the commanding generals of corps areas would henceforth be known as commanding generals, service commands, Army Service Forces.6 This change in title emphasized the fact that corps areas had become entirely supply and administrative agencies of the ASK The continued use of the designation "corps area" would have handicapped the ASF in establishing a new mission for these commands.

A conference of commanding generals of service commands was convened in Chicago on 30 July 1942. They received in advance a draft of the revised Army regulations which set forth a consolidated and simplified statement of the mission for service commands. This was accompanied by a mimeographed organization manual proposing a standard organizational pattern for each service command. General Somervell and his staff spent two days explaining the purpose of the reorganization. Somervell made it clear that he had two fundamental ideas in mind: geographical decentralization of the work of the ASF and an increase in the responsibilities of service commands.7

The official statement of mission of the service commands was contained in revised Army regulations issued on 10 August 1942.8 These regulations announced that the continental area of the United States was divided into nine service commands. The boundaries which had existed prior to the creation of the Army Service Forces were continued without change and the headquarters locations remained the same. The mission of each service command was to perform the various functions of the ASF in the field, with the exception of those relating to procurement, new construction, and the operation of depots, holding and reconsignment points, ports, and staging areas. These functions included the induction, classification, and assignment of military personnel; the training of all units and individuals assigned to service command control; the supervision of the housing and hospitalization of troops; the repair and maintenance of real property and the operation of utilities; the rendering of legal, financial, and administrative services to troops stationed within the limits of the service command; supervision of fixed signal communications; and the command of ASF training centers, except for the promulgation of training doctrine, the conduct and supervision of training, and the selection, assignment, and relief of training staff.9

All Army field installations in the zone of interior were classified into four cate-

gories.10 Class I installations were placed under the commanding generals of service commands. These included recruiting stations, induction centers, reception centers, internal security districts, motor repair shops, Ordnance and Signal Corps repair shops, enemy alien and prisoner of war camps, recreation camps, medical and dental laboratories, Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC) units, State Guard affairs, general dispensaries except the General Dispensary in Washington, finance offices, disciplinary barracks, officer procurement boards, all named general hospitals except the Army Medical Center (Walter Reed General Hospital), and ASF training centers and schools. Class II installations were those where units of the Army Ground Forces were stationed; the authority of the commanding generals of the service commands in them was confined to control of administrative, housekeeping, and supply functions. It was emphasized that the commanding general of a service command had no control over or responsibility for the Ground Forces troops who were in training at the post. Class III installations were those utilized by the Army Air Forces. Here the duties of the commanding generals of service commands were limited to fourteen specified services which included supervision of the Army Exchange Service, fixed signal communications, ordnance maintenance, special services, disbursing activities, repair and utilities operations, and laundry operations. Finally, Class IV installations were those which "because of their technical nature" remained under the direct command of a chief of a supply or administrative service in the ASF. Here again the duties of the commanding generals of the service commands were limited to certain services closely paralleling those provided stations of the AAF, plus additions which included medical service and public relations. Generally, these Class IV installations were government-owned manufacturing plants, proving grounds, procurement offices, storage depots, ports of embarkation, and certain specialized installations like the Signal Corps Photographic Center in New York, and the Army Medical Center in Washington.

This system of classification did much to clarify the duties of the commanding generals of the service commands. The new Army regulations transferred several field installations which had been under the direct control of offices in Washington to the jurisdiction of the commanding generals of service commands. The more important of these were prisoner of war camps previously under the direct control of the Provost Marshal General, the Army finance offices previously under the direct control of the Chief of Finance, the disciplinary barracks previously under the direct control of The Adjutant General, and all the named general hospitals (except Walter Reed General Hospital) formerly administered directly by The Surgeon General.

The new Army regulations were accompanied by an organization manual for service commands.11 In a foreword General Somervell emphasized the importance of supply, administrative, and other service functions in the proper conduct of the war. He explained that the new plan of organization eliminated "the previous confusion arising from a large number of independent groups reporting separately to the service commander, most of which

received instructions directly from autonomous offices in Washington." He also pointed out that one result of the reorganization must be the "maximum utilization of existing personnel" with a reduction in the number of military and civilian personnel required throughout service commands. On two types of work, commanding generals of service commands would continue to deal directly with the War Department staff without going through the Commanding General, ASE Service command inspector generals might be utilized by The Inspector General of the War Department in making local inspections and investigations. The Inspector General was accordingly given authority to communicate directly with the service commands. Second, the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, remained responsible for military intelligence in the United States. Accordingly, the director of intelligence in a service command headquarters would follow policies fixed by G-2 and would report directly to G-2.

In several respects the organization prescribed for a service command headquarters differed from that in effect at ASF headquarters. In part, this can be explained by the lack of any procurement and storage responsibilities in service commands. Also, there was no provost marshal in a service command headquarters but only an internal security division. A supply division brought technical services officers. in a service command under the immediate control of the division itself; thus instead of the old arrangement whereby a G-4 co-ordinated the work of supply officers, the officers of all seven technical services now became heads of branches in a supply division. The Army exchange branch was added to the supply division, although in ASF headquarters it was at

this time a separate administrative service. There was an administrative division in service command headquarters with three branches representing administrative services in Washington.

The service command organization realized one objective of the ASF organizational planners. There were seven divisions reporting to the commanding general of a service command, with only three branches in the commanding general's own personal office. This was regarded as a convenient number and was certainly a great improvement over the former arrangement whereby some thirty-six different officers had reported to a commanding general of a corps area.

As already mentioned, no change was made in the geographical boundaries of the old corps areas. The service commands inherited the boundaries as drawn in 1920 and as modified only slightly thereafter. With one exception, these boundaries were to remain unchanged throughout the history of the Army Service Forces. The exception resulted from the creation of a Military District of Washington (MDW) in May 1942.12 It included the District of Columbia, Arlington County, and the water supply installations for the District of Columbia lying beyond the district line.13 Army Regulations 170-10 issued in August 1942 provided that the geographical area of the MD W would be entirely removed from the Third Service Command.

Later an ASF order specified that the commanding general of the MDW would perform those services in the area which had heretofore been performed by the commanding general of the service com-

mand.14 The MDW was regarded as a tenth service command in the United States. It had three different functions. Until 1944 it had a tactical function for which it was responsible to the Eastern Defense Command. Second, its commanding general served as headquarters commandant for the War Department and as such, reported to the Deputy Chief of Staff of the War Department. Third, the MDW was a service command of the ASF in the administration of such activities as recreational camps, induction stations, and post operations at Fort Myer and later at Fort Washington and Fort Belvoir. In December 1942 the boundaries of the MDW were enlarged to include the last two posts.

Another service command was created in September 1942 as the Northwest Service Command with headquarters at Whitehorse, Yukon Territory.15 This command took over the construction and operation of the Alaska Highway, the railway between Skagway and Whitehorse, and the construction work on the Canol project. In addition, it was the supply agency for the airfields in the area. Subsequent War Department general orders specified that the Northwest Service Command would have the same powers and authorities as service commands in the United States insofar as these applied to the activities of the Army in western Canada.16 The Northwest Service Command came to an end on 30 June 1945 when its functions were transferred to the Sixth Service Command.17 The liquidation of all U.S. military activities in the area followed.

After the initial action had been taken to make service commands the field agencies of the Army Service Forces, it became necessary to keep the purpose of that arrangement constantly before all elements of the ASE On 4 August 1942, immediately after the conference in Chicago, General Somervell, called a staff conference in Washington to review the service command organization with the chiefs of the technical services. He explained that it was his intention to make the service commands the field units of the ASF for all activities except procurement and depot operations. The commanding generals of the service commands would be field general managers; the chiefs of technical services and ASF staff divisions would exercise staff supervision to insure that the work for which they were responsible was satisfactorily performed.18

To insure that service commands were performing as intended and that the reorganization was realizing its purpose, the Control Division kept one or two officers almost constantly in the field visiting service command headquarters and various posts. As a result, a small office was set up in Washington concerned with field relations,19 and which cleared all matters affecting service commands.20 This clearance procedure insured that no action was taken which impaired any of the fundamental objectives of the service command reorganization. Moreover, service commands now had a place to which they could refer any problem on which they were unable to obtain satisfaction through ordinary staff channels. General supervi-

sion of service commands through a single office in Washington continued throughout the war.

At the service command conference in July 1942 General Somervell asked each commander of a service command to submit a list of activities which he thought might be decentralized to service commands. Such lists were received during the summer and autumn of 1942. A final report of the action taken on these recommendations was transmitted to the service commanders in December 1942. For example, service commands had requested authority to appoint civilians to positions paying more than $4,600 per annum. This authority was granted by the Civilian Personnel Procedures Manual issued on 16 September 1942. Altogether some fifty suggestions were approved and another five were in the process of being carried out when the December report was made.21 These covered 75 percent of all proposals. Another opportunity was given to service commands to suggest changes in field organization in 1943 through the Program for the More Effective Utilization of Personnel .22

An important administrative arrangement established after August 1942 was the use of a single channel for the allotment of funds and of personnel for field activities. Before the service command reorganization each technical service had allotted funds for its particular activities directly to corps areas. ASF headquarters had made personnel allotments but specified the type of work to be done. New channels for the allotment of personnel and funds to service commands were set forth in January 1943.23 Thereafter, ASF headquarters made bulk allotments to service commands for all military personnel to perform all functions at Class I and

II installations except training personnel at training installations. Enlisted personnel were allotted specifically to general hospitals, training activities, recruiting and induction stations, officer procurement service offices, reception centers, and to certain other activities such as prisoner of war camps. All funds were allotted directly to service commands for various projects, and the commanding generals of service commands in turn allocated these funds to commanders of Class I and II installations. While service commands made no personnel authorization to Class III installations, they did allot funds for the hiring of civilian personnel to perform ASF type services at such installations. To Class IV installations the service commands allotted funds and military personnel for the same purposes as to Class I and II installations. Commanders at both Class III and IV installations directed the performance of all functions at their posts. They were responsible to their chiefs on some matters and to commanding generals of service commands for housekeeping operations. Subsequently, the commanders of the service commands were directed not to allot personnel to Class IV installations, but to allot funds instead and to exercise supervision over the performance of specified activities.24 When a new method of authorizing and reporting personnel was set up in June 1943, both military and civilian personnel were brought under the authorization scheme." Personnel control was entirely separated from budgetary controls.

The intricacies of personnel and fund authorizations are not pertinent to the present discussion. Here the important point is simply to note that the ASF introduced a scheme of fund and personnel authorization which strengthened the position of the commanding general of a service command as general manager and made it clearly evident that he was responsible for the efficient operation of all the services assigned to him. Both types of authorization emphasized the administrative line of command: from Commanding General, ASF, to commanding general of each service command. This arrangement did much to change the old system which had encouraged chiefs of the technical services and of the administrative services to deal directly with their own counterparts in the corps areas and to ignore the co-ordinating authority of the corps area commander.

From time to time, as new functions were started by the ASF, a concerted effort was made to manage the program through a staff division in Washington with operating responsibility vested in service commands. Thus in October 1942, when five new depots were established to distribute printed publications, each was assigned to the service command in which it was located.26 In April 1943 a new procedure was set up for the administrative settlement of claims against the government arising from military service.27 The commanding generals of the service commands were directed to take all necessary action for investigating and reviewing tort claims, and to forward recommendations to the judge Advocate General. In January 1943 labor branches were set up in service command headquarters.28 Previously, the Industrial Personnel Division of ASF headquarters had had branch offices scattered throughout the United States. Now, the service commands were made the field agencies for performing labor supply activities for the ASF. In February of the same year, Army specialized training branches were established in the headquarters of service commands.29 The next month the field activities of the Officer Procurement Service were decentralized to service commands .30 Later, the Food Service Program was established. It provided that the commanding generals of the service commands would be responsible for the operation of the program within their geographic limits.31 When a Personal Affairs Division was created in ASF headquarters, a personal affairs division or branch in each service command was also provided for.32 In October 1944 the laundry program was decentralized to the service commands.33

These examples illustrate the practice of turning things over to the service commands as new activities and programs were created. A staff division in ASF headquarters assumed supervision while service commands were directed to perform the actual operation in the field.

The Mission of the Service Commands

It may fairly be asked of the service command reorganization, and of the subsequent steps taken to make it effective: why was so much attention given to this whole effort? Why were the new arrangements regarded as so important by Gen-

TYPICAL ASF INSTALLATIONS IN A CAMP

eral Somervell, and why was so much energy devoted to making the service commands essential and efficient parts of the ASF operating organization?

The answer is to be found in General Somervell's views on organization. He believed strongly in the efficiency of an integrated, or unified, field organization. He had come to this conviction from experience in a wide variety of administrative activities, and he was acquainted with some of the theoretical writings on the subject. Moreover, the concept of joining many specialties together under a single commander or general administrator in the field, was familiar to Army officers. A combat command such as a division or an army brings together under one leader elements from all major branches in the Army. These include combat elements such as the infantry, armored force, and the artillery; combined combat and service elements such as the signal, chemical warfare, and engineer troops; and service units such as the ordnance, quartermaster, medical, and transportation units, and miscellaneous units such as military police and administrative troops. An overseas theater of operations combined all these diverse elements in a still larger command organized on the basis of a geographical area.

Yet in 1941 this concept of an overseas command as an integrated geographical organization had not been applied to the functions of the Army in the United States. The departments, and later the corps areas into which the United States was divided, were never miniature War Departments. The Surgeon General ran his own field organization, the general hospitals. The Chief of Ordnance had his own procurement offices throughout the country, his own arsenals or manufacturing plants, his own proving grounds and training centers, and his own depots for both ammunition and weapons. Other bureaus in Washington administered their own field installations.

At the time the Army Service Forces was created in 1942, it had become a firmly established tradition for each technical service to look upon its own work as being so highly specialized within the United States that it could accomplish its responsibilities only through a field organization over which it had complete administrative control and which was entirely separated from all other parts of the War Department. There were a number of "administrative services" with similar attitudes about field organization.34

The Army had for many years set up fixed or "command" installations all over the United States. These posts, camps, and stations were principally training centers. Yet each required extensive services to keep it in operation .35 With the activation of General Headquarters in 1940 the command of a fixed installation and the command of the troops in training within them was separated. The operation of these installations was the first task which the ASF inherited when the corps areas were assigned to it on 9 March 1942. The service command reorganization was an attempt to strengthen the field organization for supervising army posts and to make this same organization an integrated field structure for many other ASF activities performed within the United States. But this effort ran into the strong separatist tradition of field administration in the various technical and administrative services making up the Army Service Forces. Thus it took constant effort by ASF head-

COMMAND GENERALS OF THE SERVICE

COMMANDS AND THE MDW.

Front row,

left to right: Maj. Gens. James L. Collins, Fifth Service Command, John T.

Lewis, MD W, Lt. Gen. B. B. Someraell, Commanding General, A SF, Maj. Gens. H.

S. Aurand, Sixth Service Command, Sherman Miles, First Service Command, W. D.

Styer, Chief of Stag ASE. Back row: Maj. Gens. Philip Hayes, Third Service

Command, Richard Donovan, Eighth Service Command, David McCoach, Ninth Service

Command, Thomas A. Terry, Second Service Command, Clarence H. Danielson, Seventh

Service Command, and Frederick E. Uhl, Fourth Service Command.

quarters to maintain an integrated field organization.

General Somervell thought it expedient to exempt from service commands direction all the procurement and storage operations of the technical services. Then General Gross, the chief of the Transportation Corps, argued successfully that he needed direct control over the holding and reconsignment points, the staging areas, and the ports of embarkation if he was to ship men and supplies overseas efficiently and in balanced quantities. Therefore, a number of field installations were never placed under the "command" of the service commands. These became the Class IV installations of the service command reorganization. On the other

hand, the administrative services retained few field installations under their direct control. For example, finance offices for the payment of Army bills became parts of service commands.

The ASF endeavored to strengthen the central management of the service commands and to lessen the centrifugal forces which always threaten to pull an integrated field organization apart. Washington offices were ordered to communicate instructions directly to service commanders, or at least through them. General Somervell made strenuous efforts to keep the commanders of the service command personally informed on all phases of ASF activities so that they would know what their specialists were expected to accomplish. One method was to hold important conferences every six months where all service commanders were brought together and where the discussion leaders were chiefs of the technical services and heads of staff offices in Washington. General Somervell himself missed only one of these conferences.36

It may well be asked again what the advantages of an integrated field organization were and why so much effort was expended to make it work. Why not let each specialty in Washington go its own way and have its own field organization? General Somervell believed that a varied or multiple field organization was wasteful of manpower and of other resources. In wartime especially, he felt that he had a major responsibility as commanding general of the ASF to conserve manpower and to operate an efficient organization. The service command reorganization was a full-scale endeavor to achieve economy in war administration.

He believed strongly that an integrated field organization, when carefully constructed and loyally and efficiently operated, could realize economy in three different ways: (1) by simplifying the supervisory organization and reducing supervisory personnel requirements; (2) by promoting close collaboration in the field among individuals with common objectives; and (3) by providing common local services for various field specialties. For instance, by placing the supervision of repair and utility operations at all Army installations under a service command engineer, a single staff became responsible for checking standards maintained at posts and for providing assistance in cases of trouble. By placing Army finance offices and legal offices under single direction in the field, common interests could be promoted and conflicts of jurisdiction could be settled locally on such problems as the investigation and payment of claims. Then, when many field offices were joined under single command they could utilize common personnel, mail, communications, transportation, and other housekeeping services. A consolidation of field offices under a single commander in one city alone during World War II realized a reduction of one third of the personnel involved in the performance of housekeeping duties.

The essence of an integrated field organization is a system of dual supervision.37 Individual specialties, from head-

quarters to the lowest level of field operation, continue to communicate freely on all technical questions of policy and procedure. Command supervision, on the other hand, is concerned with the most efficient utilization of all available resources in the realization of a common objective. This system of dual supervision was real enough in the Army Service Forces but never fully understood in the field; perhaps it would be more accurate to say that it was never explicitly expounded and that this failure contributed to misunderstanding. Yet it would be entirely unrealistic to suppose that constant explanation and patience would have solved the problem of ASF field organization. An official's concept of his prestige and of the conditions under which he is willing to work at his best is not a rational proposition; it is a compound of personal ambition and other more complex motivations.

The part of the service command reorganization which created the most controversy was the inclusion of general hospitals as field installations under the commanders of the service commands. During World War II there were some sixty general hospitals scattered throughout the United States. Before August 1942 they were all "exempted" field installations under the direct command of The Surgeon General in Washington. After the service command reorganization, The Surgeon General retained technical authority over the general hospitals but not administrative control. The Surgeon General was never happy about this arrangement. He and his office voiced various objections, although none of them was ever officially presented as a formal protest. They went along with the reorganization solely because they felt required to do so. At most it was a kind of reluctant compliance.

The organization planners of the ASF staff argued that a general hospital was a large military post. The buildings had to be repaired, the utilities operated, the patients and staff fed, entertainment provided, and other services rendered. In some cases there were even prisoners of war to guard, because many German and Italian prisoners were assigned to hospital duties. ASF headquarters said in effect: We want The Surgeon General's office to worry about medical care, but we don't want an engineer on his staff to supervise repairs and utilities, we don't want a provost marshal on his staff to supervise the care and guarding of prisoners of war. So as military posts, the general hospitals were placed under the commanders of service commands; but as centers of medical care, the general hospitals remained under The Surgeon General.

From the point of view of The Surgeon General, however, the organizational arrangement was never simple. The basic mission of the general hospital was medical care, not operating utilities, feeding people, or guarding prisoners of war. Why, he asked, should the primary task be subordinated in the organizational structure to the secondary or facilitative tasks? The Surgeon General naturally felt that the basic mission might be impaired if those directing its performance could not order all supplementary services to concentrate upon the medical task. It made no difference to him that the commanding officers of general hospitals continued to be medical corps officers, that surgeons on the staff of service commanders were in constant touch with general hospitals, and that the Washington office had direct communication with each general hospital. Command was command, and it was vested in the commanding generals of the service

commands-not in The Surgeon General. The latter was on firmer ground when he pointed out that many essential field installations of other technical services remained under the direct control of chiefs of technical services; why should The Surgeon General be treated differently? And finally, the organizational prescription . for a service command headquarters seemed to reduce the service command surgeon to the status of a supply officer, an action that was scarcely reassuring to The Surgeon General in Washington. There is no doubt that psychological factors in the matter had been given too little consideration, which in retrospect can be labeled a mistake on the part of the ASF organizational planners. It might have been more satisfactory to have designated general hospitals as Class IV installations.

This difference in point of view between ASF headquarters and The Surgeon General was never resolved during World War II. The general hospitals remained administratively under the service commanders. The Surgeon General was never satisfied with that arrangement. There is much to be said for The Surgeon General's point of view, although medical control of the hospitals was never weakened as much as was sometimes intimated. From the point of view off the ASF, the field administration of general hospitals must be set down as a noble ASF experiment. In the eyes of The Surgeon General it was a failure.

In reviewing the status of service command responsibilities in 1942, ASF headquarters planners were much impressed by how far the separatist tendencies of the various Army specialties or technicians had gone toward reducing the concept of integrated field command to impotency.

The ASF endeavored to dam the flow and turn it in new directions. This endeavor may have led General Somervell and his staff associates on occasion to overstate the responsibilities of the "general administrators," i. e., the commanders of the service commands. The problem was really one of balance between technical specialty and command. There was a tendency in ASF headquarters to redress a situation of autonomy run riot with a new one too heavily weighted on the command side. Yet there were times when General Somervell tried to restore the confidence of the technical supervisors. Officer procurement is an illustration of his effort in this direction. In March 1943 ASF headquarters issued an order creating a field organization for the Officer Procurement Service. 38 Each service command was directed to establish an officer procurement branch to handle applications in the field from civilians needed as officers. But the director of this work in a service command could be selected only with the approval of the head of the Officer Procurement Service in Washington. Subsequent transfer or reassignment of personnel engaged in officer procurement activities required Washington approval. This limitation upon the authority of the service commander as "general administrator" was imposed in order to reassure the specialist that his activity would be satisfactorily conducted in the field.

Three specific problems that arose during World War II will illustrate the ASF's continuing concern over field organization. These problems were the supervision of Class IV installations, the handling of labor shortages, and the prescription of a uniform internal organization for the service commands.

The Supervision of Class IV Installations

As noted earlier, an essential feature of the service command reorganization was the classification of all military installations within the United States into four major groups. To each of these the commanding general of a service command had a somewhat different relationship. Class I installations were the field installations carrying out the direct work of the service command, like a prisoner of war camp or an induction center. Here the service command supervisory authority was general, subject to the technical supervision of the staff offices of ASF headquarters. Class II installations were large military establishments where Army Ground Forces troops were in training. Here the service command supervised all the housekeeping operations. Class III installations were bases of the Air Forces. The controversy over the supervision of certain housekeeping activities within them has been related above. Class IV installations were field offices of the technical services of the ASF. In other words, these were separate field installations of operating units of the ASE What relations were desirable between these installations and other parts of the Army Service Forces was the question.

It will be recalled that General Somervell in 1942 decided it was not expedient to create an integrated field organization for all ASF activities. Difficulties arose, however, when the ASF failed to distinguish between two very different types of field installations of the technical services. One type was the procurement offices and the storage centers. These operated principally with officer and civilian personnel. Only the large depots among them occasionally had to have enlisted personnel for operating duties. The second type was the training installation where technical service troops were trained.

Instead of drawing a clear distinction between these two types of installations, the ASF at first proposed to make all technical service training posts Class I installations. This proposal was opposed by chiefs of technical services. The result was a compromise. Replacement training centers and schools of the ASF were placed under service commands "except for promulgation of training doctrine, scheduling programs, the conduct and supervision of training, and the selection, assignment, and relief of training staff and faculty personnel assigned to the schools or the replacement training centers." This was an obviously bifurcated arrangement. Commanding generals had "command" of training centers, and yet the most important phases of training were immediately excepted from their command. Technical services and staff divisions with training responsibilities continued to prescribe the curriculum and prepare training programs. They determined training loads and assigned and relieved training personnel. There was little left for service commands to do other than manage the installation at which the training took place. In December 1942 an attempt was made to clarify training responsibilities.39 This new statement enlarged service command authority to include inspection of training activities and recommendations for changes in training operations. Aside from this, chiefs of technical services and staff divisions continued to be responsible for training. The change was not particularly helpful.

Two types of training were operated

entirely by service commands. One of these was the Army Specialized Training Program. The other was Women's Army Corps training at three WAC training centers assigned to the commanding generals of the service commands in which they were located.40 WAC basic training was supervised by the ASF Director of Military Training through service command channels. In other cases the supervision of training activities in the ASF was more complicated.

In May 1943 it was announced that thereafter training centers and schools would be designated as under the command of a chief of a technical service, an ASF staff division, or a service command.41 When placed under a service command, ASF headquarters would continue to be. responsible for the promulgation of training doctrine, the establishment of student quotas, and the preparation of training programs. In addition, the following schools were made Class IV stations: The School of Military Government under the Provost Marshal General; Edgewood Arsenal under the Chief of Chemical Warfare Service; Camp Lee under The Quartermaster General; Aberdeen Proving Ground under the Chief of Ordnance; Ft. Monmouth and Camp Murphy under the Chief Signal Officer; and Carlisle Barracks under The Surgeon General. These provisions were amplified in June 1943.42 Chiefs of the technical services and ASF staff directors became responsible for all training activities at Class IV installations and at the posts just mentioned, except that commanding generals of service commands would supply or construct training aids, allot training ammunition, and allot and obligate special field exercise funds.

After the summer of 1943 training within the ASF was carried out according to the following general organizational pattern. Commanding generals of service commands were directly responsible for the training of special training units (illiterates), Army specialized training units, WAC units and detachments, station complements, and special schools such as those for cooks and bakers. ASF technical services and staff divisions were responsible for training troop units and individuals to be sent overseas to perform ordnance, quartermaster, medical, signal, engineer, transportation, chemical, fiscal, chaplain, special services, military police, military government, legal, adjutant general, and intelligence duties. Actually, the distinction was not as clear-cut as this. Camp Crowder in Missouri, for example, a Signal Corps training center, was a Class I installation. This meant it was under the commanding general of the Seventh Service Command except for training doctrine, training programs, supervision of training, and the selection of training staff. The same was true of Ft. Leonard Wood where Engineer troops were trained, of Ft. Warren where Quartermaster troops were trained, and of Camp Gordon Johnston where Transportation troops were trained. These were Class I training centers. Even Ft. Belvoir, the major training center of the Corps of Engineers, was a Class I installation of the Military District of Washington. Yet in reality, the commandant of each school or the commanding general of each training center was designated by the chief of a technical service, and all training activities were actually specified by the appropriate technical service.

Personal observation 'convinced the author that service command responsibility at a Class I training installation where Engineer troops were trained was not essentially different from that at a Class II post where AGF troops were trained. It would have been simpler to make all technical service training centers Class II installations. This was never officially done. If these ASF training installations had been designated Class II installations, then their operation would have been under the supervision of a service command, but all training programs would have been supervised by ASF offices in Washington. Instead, the ASF tried to distinguish between the training and the supply work of the technical services by calling the first a Class I field office and the second a Class IV field office. As a result, a number of training posts later had to be transferred to Class IV to satisfy technical service wishes.

At a Class IV installation the service command was responsible for a designated list of duties. The last attempts to state these specific duties were made in 1945.43 In general, the arrangement was that a technical service looked to a service command for supervision of those activities at a Class IV installation which did not fall within its own competence. Thus the service command supervised medical service, if there was any, at an Ordnance installation, and ordnance maintenance operations, if any, at a Quartermaster depot. Accordingly, there was just one supervisory force in the field for the varied work of the ASF in operating a training center, a depot or a staging area. The technical service named the field commander for its depot, its procurement office, or any other specialized (or Class IV) installation. But this officer looked to the service command not to his superior in Washington-in providing internal services such as motion pictures for recreation, post exchanges, or utilities.

This was the best the ASF could do in trying to tie together the field offices of the technical services and the service commands. One other measure should be mentioned. The ASF asked the Chief of Engineers to set up "division" offices paralleling the service commands. The division engineer ran certain exempted activities for the Chief of Engineers in Washington, such as the letting and supervision of construction contracts. But the division engineer also worked for the service command in supervising the maintenance of physical properties and the operation of utility systems. A deputy division engineer for repairs and utilities was appointed by a division engineer and became in effect the service command engineer as well. Similarly, the Transportation Corps in 1943 set up zone transportation offices which were coterminous with service command boundaries. The zone transportation officer supervised some activities for the Chief of Transportation and on other matters was the transportation officer on the staff of the commander of a service command. This arrangement worked fairly well in practice.

But the ASF never fully settled the distinction between a Class I and a Class IV installation. The author has come to the conclusion that under the conditions prevailing during World War II, all technical service activities in the United States outside of Washington, except training, should have been classified as Class IV installations. Large Army installations utilized for training purposes by the technical services

and ASF staff divisions should have been designated Class II installations, with a post commander appointed by and responsible to a commanding general of a service command and a training center commander appointed by and responsible to a technical or administrative service chief in Washington. This conclusion seemed to be the prevailing one among ASF organizational planners as World War II came to an end.

The Handling of Labor Supply Problems

in the Field

Originally, the ASF assigned manpower problems in the field arising out of technical service procurement activities to the service commands. Manpower difficulties were essentially an area problem. Labor shortages appeared in localities such as the Buffalo area or the Los Angeles area. Oftentimes the solution involved a number of adjustments within a particular community-better housing, recreational facilities, better transportation arrangements, an adjustment in shopping hours, and similar action. Since the technical services had separate field organizations and set up their local procurement offices in different cities, the ASF assigned labor relations and labor supply activities to the service commands. This did not prove a satisfactory arrangement.

In December 1943 new instructions were issued to define more precisely the labor functions of the various parts of the ASF and of the AAF.44 In part, they were necessary in order to implement a memorandum from the Under Secretary dated 5 November 1943. In part, they dealt with an internal organization problem of the ASK The circular specified that the technical services would give attention to the labor situation in the placing of contracts, in following up on production performance, and in preparing estimates of labor requirements of contractors. Furthermore, technical services would "assist" service command labor branches in carrying out recommendations for solving labor problems. Moreover, they were to call upon service commands for assistance whenever necessary. When two or more technical services had an interest in a plant of a single contractor, they would work out with the service command a single labor responsibility for the plant.

Labor branches of the service commands were supposed to exercise general supervision over the labor activities of all War Department components in the field and provide assistance to any procurement office in meeting its labor problems. Furthermore, service commands were to keep the technical services and the procurement agencies of the Army Air Forces informed on labor market conditions and make recommendations for solving labor shortages. The service command labor branches were also designated as the official War Department agencies for liaison with local and regional offices of federal, state, and local government agencies concerned with manpower matters. This arrangement was intended to strengthen service command responsibility for handling labor problems in the field. At the same time, it recognized that the technical services could not be divorced from labor supply matters.

Manpower shortages grew more stringent as the war progressed. By early 1944 labor shortages appeared to be the single greatest obstacle to the realization of procurement schedules. The War Manpower Commission in March 1944 determined to

establish manpower priorities committees in about one hundred areas of labor shortages. Previously, such committees had been used on the west coast and then in three other regions. At the same time, the War Production Board extended its production urgency committees into each labor area where a manpower priorities committee was established. This action on the part of the WMC and the WPB compelled the Army Service Forces to establish some organization for dealing with manpower and production problems in many different localities.

The director of materiel in ASF headquarters, General Clay, urged a new regional organization rather than the utilization of service commands for this function. His recommendations were accepted by General Somervell, and an ASF regional representative was designated for each of the thirteen regions in which the War Production Board had divided the United States.45 The representative for each of these regions was a technical service officer in charge of an important activity in the area. Thus, for the Boston region the ASF regional representative was the commanding general of the Springfield Ordnance District. Other ASF regional representatives were as follows: New York, commanding officer of the New York Ordnance District; Philadelphia, commanding general of the Philadelphia Signal Depot; Atlanta, division engineer; Kansas City, commanding officer of the Kansas City Quartermaster Depot; Denver, commanding general of the Rocky Mountain Arsenal of the Chemical Warfare Service; Seattle, commanding officer of the Seattle ASF Depot.

A labor adviser was also named for each ASF regional representative. In six instances, this labor adviser was the head of a labor branch of a service command. In the other cases, the labor adviser came from the staff of a technical service. In one instance, he was named directly by the Industrial Personnel Division of ASF headquarters.

Each ASF regional representative was directed to organize an advisory committee representing the technical services, the Army Air Forces, and the service commands in the region. The regional representative was authorized to arrange for appropriate representation on all production urgency and manpower priorities committees set up in his region. The same representative was to serve on both committees and represent all Army contractors of the area on production urgency and manpower priorities matters. The area advisory committee assisted each area representative in fulfilling these responsibilities. Staff supervision of production problems in every region was vested in the Production Division under the ASF Director of Mat6riel, and staff supervision of all manpower problems was vested in the Industrial Personnel Division under the ASF Director of Personnel.

The establishment of these regional representatives introduced a whole new area organization into the ASF. There were now thirteen regional areas on production manpower problems, the areas following WPB regional boundaries. This coincided with no existing field boundary lines previously employed by the War Department. The ASF regional representative was potentially capable of exercising considerable authority in each region. On the other hand, he had an administrative responsibility which demanded his first allegiance. Often his reputation and his

future depended upon how Well he performed his job as head of an Ordnance district, of a Signal depot, of an Engineer division, or of a Chemical Warfare arsenal. His responsibilities as ASF regional representative were merely an added duty, which naturally tended to be of secondary interest. In fact, in many instances these individuals did almost nothing in their capacity as ASF regional representatives.

The labor advisers turned out to be the most important individuals in exercising supervision over local manpower priorities and production urgency committees. Where the labor adviser worked for both a service command and a regional representative, he found himself with divided loyalties. The head of the Labor Branch of the Third Service Command with headquarters in Baltimore, for example, was also regional labor adviser for the ASF third region with headquarters in Philadelphia. Thus he had two different headquarters and two regions with different boundaries. The situation was even worse on the west coast where the head of the regional branch of the Ninth Service Command with headquarters in Salt Lake City also served as labor adviser to the ASF regional representative with headquarters in San Francisco. Under such circumstances it was surprising that labor advisers accomplished as much as they did. In most instances it was at best a thankless task.

The entire setup was severely criticized by the commanding general of the Third Service Command at the Biloxi Service Command Conference in February 1945.46 An investigation by General Somervell's Control Division after this conference revealed that the organizational difficulties were too deep-rooted to be adjusted in the closing weeks of the European war. The

simple fact was that the technical services had first responsibility for procurement deliveries and were determined to handle their labor problems as a part of that responsibility. Never were they willing to turn labor supply administration over to service commands. The only completely satisfactory solution would have been an entirely new area organization for all procurement activities of the ASK But this was out of the question at the time. It had once been proposed in 1943 and disapproved. There was no point in raising the issue again. Because it was expected that labor supply difficulties would ease greatly with the defeat of Germany, there was little disposition in ASF headquarters to change what was admittedly a bad situation.

It remains a fact that the Army Service Forces never solved the problem of a unified field structure for handling labor supply problems. On this subject the interests of the technical services and the service commands clashed. The technical services would not leave supervision of an important procurement matter, whether it pertained to manpower or supply, to the service commands. In consequence the ASF never had an effective field organization for labor supply questions. If the war had lasted longer, and labor matters had become more critical, the ASF probably would have had to devise a really effective field organization to handle manpower procurement problems. Whether this should have been a reaffirmation of the service command status as a field supervisory organization for general ASF work, or whether it should have been a new, integrated field organization for procurement operations, no one can say.

Organization Within Service Commands

A fundamental element of administrative procedure which went into the service command organization was the establishment of a common internal organizational structure for all service commands. As noted above, the staff organization prescribed for service commanders introduced arrangements which differed from the organization of the ASF in Washington. The most notable of these was the creation in service command headquarters of a supply division with ordnance, quartermaster, engineer, signal, medical, and chemical warfare branches. This in effect made technical service officers not staff officers of a commander of a service command, but branch chiefs of a single staff officer in service command headquarters called a director of supply. The technical service chiefs in Washington were not enthusiastic about this arrangement, which may have been one reason why they sometimes resisted the transfer of any extensive technical supervisory authority of their own to service command channels.

A new organizational manual for service commands was issued in December 1942.47 It modified the existing structure but made no important changes. Some new branches were created in service command headquarters, and the Army exchange branch was transferred from the supply division to the personnel branch. At the post level, intelligence work was separated from internal security.

A more radical change in post organization was made when in September 1943, by a War Department memorandum, posts were directed to integrate all maintenance activities in order to improve maintenance service.48 This entailed a fiscal consolidation, a consolidation of administrative activities, a unification of command, and an interchange of skilled and unskilled personnel. Combined maintenance shops were set up at each post to perform third and fourth echelon maintenance along functional lines. Thus at each post there was a combined maintenance shop immediately under the director of supply and service. The shop was equipped to serve as an automotive shop, an armament and instrument shop, a clothing and equipment shop, an electrical equipment shop, a machine shop, and a paint shop. In addition, there were provisions for a single point of production control, a single shop supply unit, and a single shop salvage unit. This had the effect of breaking down technical service differentiations in maintenance activities in favor of a purely functional shop organization. In other words, no longer did the post signal officer run a signal maintenance shop or the post quartermaster a quartermaster shop. Instead, a combined maintenance shop handled all maintenance activities divided up into six functional groups.

This action was intended to improve maintenance work at posts, particularly through a better utilization of skilled labor. There had been much competition at posts for electricians, carpenters, painters, and other skilled workmen. The system of separate technical service shops made such competition inevitable, since all had an urgent need for competent mechanics. The combined maintenance shop was the answer to this situation.

When ASF headquarters in Washington was undergoing reorganization in October and November 1943, the ASF chief of

staff, General Styer, decided to reorganize service command headquarters so that they would parallel ASF headquarters more closely. At the time, the chiefs of technical services were still unhappy about the service command organization which made technical service officers branch units under a director of supply. This was demonstrated at the Third Service Command Conference in Chicago in July 1943 when The Surgeon General recommended that the service command surgeon should report directly to the commanding general of a service command. He pointed out that the surgeon had personnel and training problems as well as medical service and supply problems.49 In his closing remarks General Somervell disapproved this recommendation mainly on the ground that it would require a change in the status of each technical service officer in a service command headquarters. He added that he expected the commanding general of each service command to know his staff thoroughly and to be personally acquainted with the fiscal staff, the exchange staff, the judge advocate staff, and also with the technical staff. "Certainly you have got to talk to your doctor. You have to know what he has to say, and I expect you to do that." 50

In November 1943 Styer had a letter dispatched to the commanding general of each service command which expressed the desire that the headquarters of each service command conform as closely as practicable to the organization of ASF headquarters.51 This meant that each service command headquarters was to have organizational units including the technical services, corresponding in function to those in ASF headquarters. There followed a new organization chart and a new statement of functions. (Chart 1) The quartermaster branch, the ordnance branch, and the other branches under the director of supply were abolished and replaced by a service command quartermaster, a service command ordnance officer, a service command signal officer, a service command surgeon, a service command transportation officer, and a service command chemical warfare officer-all reporting directly to the commanding general of the service command. The service command engineer already enjoyed this status. The organization chart and the statement of functions explained that technical service officers in service command headquarters would act as staff officers and advisers to the commanding general on their technical service functions.

The new organization increased the number of staff units reporting directly to a commanding general of a service command and at the same time, encouraged chiefs of the technical services in Washington to deal directly with technical service officers in service commands. This was the price of getting technical services in Washington to use service command channels in the field. Moreover, a type of organization in the field different from ASF organization in Washington simply did not prove feasible.

A further organizational revision was presented to service commands in a letter in December 1943.52 Its purpose was to give effect to many recommendations

CHART 1 - ORGANIZATION OF SERVICE COMMAND HEADQUARTERS: 8 DECEMBER 1943

which had been received. The only structural change it set up was the addition of two new divisions under the director of supply. The statement of functions was somewhat more elaborate in order to provide more detailed instructions. An introduction said that a service command could not alter or transfer functions from one staff directorate to another without the prior approval of the Commanding General, ASE The statement of functions also made it clear that the director of supply was expected to be the staff officer for co-ordinating storage, distribution, maintenance, and salvage activities. At the same time it was apparent that he would have to work through the technical service officers in service command headquarters. In the statement on technical service officers it was emphasized that these were likewise staff officers of the service command and would function as such. The letter also included an organization chart and statement of functions for posts. Their organization closely paralleled that provided for service command headquarters, including a post quartermaster, a post ordnance officer, a post surgeon, a post signal officer, a post chemical warfare officer, and a post transportation officer.53 Despite the strong effort to establish a functional organization within posts, the system did not meet expectations.

In January 1945 ASF headquarters completed an important supply study pertaining to returns to stock.54 Behind it was the fact that posts had not been obtaining prompt shipping instructions from depots on excess stocks at the posts. In turn, depots were failing to carry excess stocks as a supply asset with a possibly corresponding reduced need for procurement. The survey found that in large part the difficulty arose out of post maintenance work.

Depots were reluctant to accept supplies from posts for return to stock without inspecting them and oftentimes without further repair. One of the conclusions reached was that the combined shop operation at posts had tended to reduce technical service sense of responsibility for reporting property to depots. Thus technical service officers continued to be responsible for storage and issue of property at posts but were no longer responsible for its maintenance. This separation of responsibility had an adverse effect upon the prompt repair and return to stock of repairable items. As a result of the survey a new supply organization was directed for posts.55 The combined maintenance shops might be continued at posts where its operation was proving satisfactory. Where it was not, the maintenance responsibility was to be returned to each technical service officer at a post. The post director of supply simply became a staff officer co-ordinating the maintenance activities of the various post technical service officers. With this experiment with combined shops, another attempt of the ASF to effect a functional organization came to an end. In only a few cases were combined shops retained.

One further major organizational change was introduced in service command headquarters in June 1945.56 Many service commanders had complained that their director of personnel was overburdened. His six divisions (military personnel, civilian personnel, special services, personal affairs, chaplains, and informa-

tion and education) made up one third of the total strength of a service command headquarters staff. The execution of various military and civilian personnel policies; the handling of strength control; and the supervision of separation center, reception station, and redistribution station activities had long since reached the point where they required the full attention of a director of personnel. Accordingly, service commands were permitted to establish a director of individual services supervising special services, information and education, personal affairs, and chaplains. This left the director of personnel in charge of direct military and civilian personnel. All service commands elected to make this change.

By 1945 the role of the service command in ASF organization was fairly well understood. The biggest contribution of the service command to ASF organization was as a supervisor of Army posts in the zone of interior. There were about one hundred large installations scattered throughout the United States where AGF troop units and replacements were trained. At each of these there was a post commanding officer responsible to the commanding general of a service command. The job of a post commander was to service the Ground Forces troops and activities located on the post. The service command provided the supervisory organization. In a sense the Ground Forces were in a position like that of guests at a hotel. The principle laid down was that the guests were always right, which meant that the post commander should comply with the wishes of Ground Forces units.

Only one important issue ever arose with the Ground Forces in connection with the operation of Class II installations.

With the growing manpower stringency in 1943, the ASF was pressed to find the available personnel to perform all station complement duties. As a result, the War Department issued a memorandum ordering Ground Forces troops to perform certain duties for themselves at posts.57 These included the distribution of mail within units, the unloading of supplies at distribution points, the guarding and policing of areas assigned to AGF units, the maintenance of sanitary conditions in these areas, the operation of unit infirmaries, first and second echelon maintenance and third echelon maintenance when units and facilities for this were available, firing of small furnaces or stoves, the maintenance of unit records of all kinds, and the operation of target ranges and other training aids. In addition, Ground Forces troops were directed to assist the ASF in the policing of community areas adjacent to posts, in guarding garrison prisoners, and in meeting peak supply shipments or the reception of peak personnel loads at a post. In unusual circumstances the Ground Forces were also asked to assist the service commands in internal security duties. The AGF reluctantly agreed to render this assistance. It could hardly have done otherwise since its commander had long been critical of the growing number of specialized service units.

At large ASF training installations, service commands provided the same services. In a few instances the post commander was designated by the technical service or staff division responsible for the training. When this was done, however, the post commander was responsible to the service command for the internal management of his facility, rather than to

the chief of a technical service or to a, staff director.

The extent of service command supervision at arsenals, government-owned plants, procurement district offices, transportation offices, engineer division offices, and laboratories was more restricted. The important difference was the absence of any large number of enlisted personnel who had to be housed and cared for at these installations. The essential distinction between a Class II and Class IV should have been that one had the primary characteristics of a military post in the customary sense of that word, and the other resembled a manufacturing or great warehousing enterprise.

It was the concept of geographical unity, and the obvious need for single direction of the management of a military installation that gave the service commands vitality and which made them an essential element of the ASF operating organization.

As operating agencies of the ASF, the service commands, like the technical services, were large organizations. As of 31 July 1943 total operating civilian and military personnel of the nine service commands and the Military District of Washington (as far as ASF work was concerned) amounted to 751,911. This was 45 percent of the total ASF operating strength. The strength of the service commands varied as follows:58

|

First Service Command |

31,246 |

|

Second Service Command |

50,749 |

|

Third Service Command |

60,548 |

|

Fourth Service Command |

175,166 |

|

Fifth Service Command |

42,600 |

|

Sixth Service Command |

42,050 |

|

Seventh Service Command |

76,530 |

|

Eighth Service Command |

147,952 |

|

Ninth Service Command |

106,991 |

|

Military District of Wash |

18,079 |

Alongside the technical services, the service commands of the ASF were a second type of operating agency. Set up by geographical areas, the service commands were the regional organizations for most ASF activities other than procurement, supply, and certain other specialized tasks of the technical services. But the service commands never became complete and integrated replicas of ASF headquarters on a regional basis.