CHAPTER XXVIII

The Southern Islands

As long as the decisive struggle for control of the Philippines was being fought on Luzon, the islands to the south were safe from invasion. At no time during the first four months of the war did General Homma have sufficient troops to conduct operations simultaneously in both areas. Having established a foothold on Mindanao, at Davao, late in December, he had been forced to limit operations in the south to air and naval reconnaissance. It was not until April, as the Bataan campaign was drawing to a close, that Homma had a large enough force to embark on the conquest of the southern islands. The opening gun of this campaign sounded on 10 April, one day after the Bataan campaign ended.

Mindanao, the southernmost island in the Philippine Archipelago, has an area of more than 36,000 square miles and is second in size to Luzon. Its coast line is irregular and its bays afford shelter at many places for a hostile fleet. Much of the beach line is flat and two large river valleys offer easy routes of advance into the interior. The Zamboanga Peninsula jutting westward from the center of the island into the Sulu Sea is virtually indefensible and easily cut off at its narrow neck from the rest of Mindanao. Along the northeast coast is the Diuata Mountain range; in the wild and largely unexplored interior extinct volcanoes rise to formidable heights.1

Transportation and communications on Mindanao were greatly inferior to those on Luzon. There were no railroads on the island and only two highways. The longest of these, Route 1, followed a circuitous route from Digos on the east coast across the narrow waist of Mindanao to Cotabato then northward to the northeast tip of the island. The stretch of road between that point and Davao was still under construction in 1941. Route 3, named the Sayre Highway in honor of the Philippine High Commissioner, extended southward through central Mindanao for a distance of about 100 miles, linking the northern and southern arms of Route 1. The northern stretch of the road was well surfaced and usable in all weather, but the southern portion had a clay surface which, after a rain, "reminded one of the glutinous stuff found near the Black Hills in South Dakota."2

Additional means of transportation on Mindanao were provided by small vessels,

[498]

which moved freely along the coast and up the island's two large navigable rivers, the Agusan and Rio Grande de Mindanao. The first flows north through a wide and marshy valley on the inland side of the Diuata Mountains on the east coast to empty into the Mindanao Sea. The second, called simply the Mindanao River, flows south and west through central Mindanao, parallel to the Sayre Highway and Route 1, to empty into Moro Gulf at Cotabato.

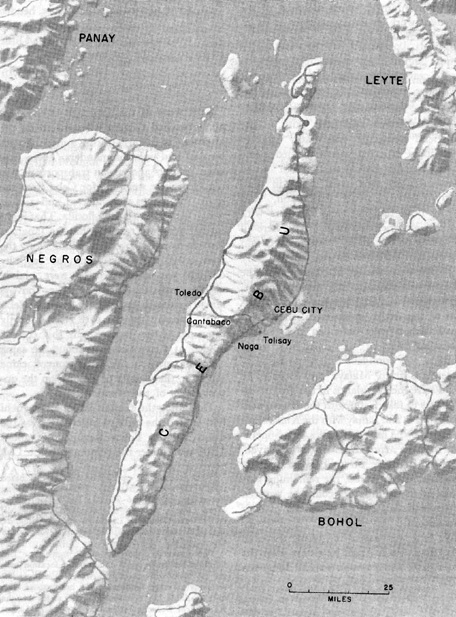

Between Mindanao and Luzon lie the islands of the Visayan group, the most important of which are Cebu, Panay, Negros, Leyte, and Samar. Most of these islands consist of a central mountain area surrounded by coastal plains. Panay, split north and south by a comparatively large central plain between two mountain ranges, has the largest level area of the group. Cebu, the most mountainous, has the least.

The road net throughout the Visayas is generally the same: a primary coastal road all or part way around each island, with auxiliary roads linking important points in the interior to the ports along the coast. None of these roads, in 1941, had more than two lanes, and most were poorly surfaced and winding. On the most highly developed of the islands-Cebu, Negros, and Panay-there were short stretches of railroad. Coastal shipping supplemented the road and rail system in the islands and linked the islands of the Visayan group with each other and with Mindanao.

The defense of Mindanao and the Visayas- comprising a land area half again as large as Luzon-rested with the Visayan- Mindanao Force, commanded by Brig. Gen. William F. Sharp, who had his headquarters initially on Cebu. This force was composed almost entirely of Philippine Army troops. Of the five divisions mobilized, in the south, only three, the 61st, 81st, and 101st, remained in the area. The other two divisions, the 71st and 91st, moved to Luzon, leaving behind their last mobilized regiments, the 73d and 93d. In addition, a large number of provisional units and some Constabulary units were formed on the outbreak of the war.

General Sharp's problems were similar to those faced by the commanders on Luzon. His untrained men lacked personal and organizational equipment of all types. There were not enough uniforms, blankets, or mosquito bars to go around, and though each man had a rifle-the Enfield '17- not all understood its use. Moreover, many of the rifles were defective and quickly broke down. Machine guns of .30- and .50- caliber were issued, but many of these were defective also and had to be discarded. Spare parts for all weapons were lacking and guns that ordinarily would have been easily repaired had to be abandoned. There were no antitank guns, grenades, gas masks, or steel helmets for issue, and the supply of ammunition was extremely limited.3

General Sharp's most serious shortage was in artillery weapons. At the start of the war he had not a single piece in his entire command and as a result organized the artillery components of his divisions as infantry. On 12 December he received from Manila eight old 2.95-inch mountain guns, three of which were lost two weeks later at

[499]

MAJ. GEN. WILLIAM F. SHARP AND HIS STAFF, 1942. Back row, standing left to right: Maj. Paul D. Phillips (ADC) and Capt. W. F. O'Brien (ADC). Front row, sitting left to right: Lt. Col. W. S. Robinson (G-3), Lt. Col. Robert D. Johnston (G-4), Col. John W. Thompson ( C of S ) , General Sharp (CG), Col. Archibald M. Mixson ( D C o f S ) , Lt. Col. Howard R. Perry, Jr. (G-1), Lt. Col. Charles I. Humber (G-2), and Maj. Max Weil (Hq Comdt and PM). |

Davao. The remaining five pieces constituted Sharp's entire artillery support throughout the campaign.

To alleviate the shortages in clothing, spare parts for weapons, and other equipment, factories, staffed and operated by Filipinos, were established. They were able to turn out such diverse items as shoes, hand grenades, underwear, and extractors for the Enfield. Unfortunately there was no way to manufacture small-arms ammunition or artillery pieces, and these remained critical items until the end.

General Sharp's mission, initially, was to defend the entire area south of Luzon. When organized resistance was no longer practicable, he was to split his force into small groups and conduct guerilla warfare from hidden bases in the interior of each island. Food, ammunition, fuel, and equipment, were to be moved inland, out of reach of the enemy, in preparation for such a contingency. Those supplies that could not be moved were to be destroyed.4

At the end of December, after he had made his decision to withdraw to Bataan, General MacArthur informed the Visayan- Mindanao Force commander that he could expect no further aid from Luzon and instructed him to transfer the bulk of his

[500]

troops to Mindanao for the defense of that island and its important airfield at Del Monte.5 The move to Mindanao began immediately and was completed early in January. With Sharp's headquarters and most of the troops on Mindanao, the Visayas assumed a secondary importance in the defense of the south. In the event of attack it would be virtually impossible to reinforce any of the islands in that group from Mindanao. Each of the six defended islands- Cebu, Panay, Negros, Leyte, Samar, and Bohol-was now dependent upon its own garrison and resources to meet a Japanese invasion.6

The organization of the Visayan-Mindanao Force established early in January lasted only about one month. On 4 February, in an effort to facilitate the delivery of supplies expected shortly from Australia, USAFFE assumed direct control of the garrisons on Panay and Mindoro, both a part of General Sharp's command. A month later, a week before MacArthur's departure for Australia, the remaining Visayan garrisons were separated from General Sharp's command which was then redesignated the Mindanao Force. The five garrisons in the Visayas were then organized into the Visayan Force and placed under Brig. Gen. Bradford G. Chynoweth, who had commanded on Panay. As coequal commanders, Sharp and Chynoweth reported directly to higher headquarters on Corregidor.7 This separation of the Visayan-Mindanao Force clearly reflected MacArthur's desire to insure the most effective defense of Mindanao, which he hoped to use as a base for his promised return to the Philippines.

Japanese planning for operations in the south did not begin until late in the campaign. The initial 14th Army plan for the conquest of the Philippines contained only brief references to Mindanao and the Visayas, which were expected to fall quickly once Manila was taken. During the months that followed the first landing, Homma showed little interest in the islands south of Luzon. But even had he desired to move into that area, he would have been unable to do so. In February the campaign on Bataan had reached a stalemate. Imperial General Headquarters, informed of Homma's situation and worried over his slow progress, pressed for an early end to the Philippine campaign and finally, early in March, sent the needed reinforcements. With them came orders to begin operations in the south concurrently with those against Bataan and Corregidor.8

It was several weeks before the troops scheduled for use in the south reached the Philippines. The first contingent came from Borneo and arrived at Lingayen Gulf on 1 April. It consisted of Headquarters, 35th Brigade, and the 124th Infantry, both from the 18th Division. Led by Maj. Gen. Kiyotake Kawaguchi, the brigade commander, this force, with the addition of 14th Army supporting and service troops, was organized into a separate detachment known as the Kawaguchi Detachment. Four days later elements of the 5th Division from Malaya, consisting of the headquarters of Maj. Gen. Saburo Kawamura's 9th Infantry Brigade and the 41st Infantry, reached Lin-

[501]

gayen. With these troops, augmented by service and supporting troops, Homma formed the Kawamura Detachment. These two detachments, plus the Miura Detachment already at Davao, constituted the entire force assigned the conquest of the southern Philippines.9

The creation of the Visayan Force on 4 March had brought a change in commanders and a renewed vigor to the preparations for a prolonged defense of the islands in the Visayan group. In the force were about 20,000 men organized into five separate garrisons, each with its own commander. The largest of these was Col. Albert F. Christie's Panay Force which consisted of the 61st Division (PA), less the 61st and 62d Infantry, and the 61st Field Artillery which Sharp had taken to Mindanao. To replace these units, the island commander had organized the 64th and 65th Provisional Infantry Regiments. The addition of miscellaneous Constabulary troops brought the total of Christie's garrison to about 7,000 men.

Col. Irvine C. Scudder, commander of the troops on Cebu, where Visayan Force headquarters was located, had about 6,500 troops, including the 82d and 83d Infantry (PA), the Cebu Military Police Regiment, a Philippine Army Air Corps detachment, and miscellaneous units. On Negros were about 3,000 troops under the command of Col. Roger B. Hilsman, who had led the force opposing the Japanese landing at Davao. Leyte and Samar were held by a hastily improvised force of 2,500 men led by Col. Theodore M. Cornell, and Bohol by about 1,000 men under Lt. Col. Arthur J. Grimes.10

General Homma's preoccupation with Bataan gave General Chynoweth, the Visayan Force commander, an additional month in which to make his preparations. Much had already been accomplished when he assumed command, and under his direction the defenses were rapidly brought to completion. On Cebu and Panay, where the defenses were most elaborate, the men had constructed tank obstacles, trenches, and gun emplacements, strung wire, and prepared demolitions. Airfield construction was pushed rapidly on all the islands. Panay alone had eight. Negros had an air and sea warning system and was able to alert the other garrisons of the approach of enemy planes and ships. Most of the work on these and other defenses was done by civilians, thus leaving the troops free to continue their training.11

Perhaps the most interesting feature of the preparations for the defense of the Visayas was the program known as Operation Baus Au, Visayan for "Get it Back." Initiated by General Chynoweth during his tenure as the commander of the Panay garrison and then adopted on Cebu, Operation Baus Au was the large-scale movement of goods, supplies, and weapons into the interior for use later in guerrilla warfare. Secret caches were established in remote and inaccessible places, and at mountain hideouts which could be reached only by steep, narrow trails barely passable for a man on foot.

[502]

The 63d Infantry, which did most of the cargador work on Panay, adopted as its insignia a carabao sled loaded with a sack of rice and bearing the inscription Baus Au.12

The effect on the civilian population of Operation Baus Au and other measures for a prolonged defense in the interior was unfortunate. The Filipinos felt that they were being abandoned and their faith in the American protector was badly shaken. What they expected was a pitched battle at the beaches ending in the rout of the enemy. "They took great pride in their Army," noted Colonel Tarkington, "and having been indoctrinated for years with the idea of American invincibility, were all for falling on the enemy tooth and nail and hurling him back into the sea."13

Japanese knowledge of conditions in the Visayas was accurate and fairly complete. Though they did not know the exact disposition of the troops in the area, they knew which islands were defended and the approximate size of the defending force. Homma was confident that with the reinforcements from Malaya and Borneo he could seize the key islands in the group. His plan was to take Cebu with the Kawaguchi Detachment and Panay with the Kawamura Detachment. These two forces, in co-operation with the Miura Detachment at Davao, would then move on to take Mindanao. That island conquered, the remaining garrisons in the Philippines could be reduced at leisure if they did not surrender of their own accord.

No time was wasted in putting this plan into effect. On 5 April, four days after the Kawaguchi Detachment reached Lingayen Gulf, it was aboard ship once more, headed for Cebu. With 4,852 trained and battle-tested troops, General Kawaguchi had little reason to fear the outcome.

The Cebu Landings

First word of the approach of the Japanese reached General Chynoweth on the afternoon of 9 April, during a meeting with his staff and unit commanders. Three Japanese cruisers and eleven transports, it was reported, were steaming for Cebu from the south. All troops were alerted and a close watch kept on the enemy flotilla. That night further news was received that the Japanese force had split in two, one. sailing along the west coast, the other along the east. By daylight the enemy vessels were plainly visible, with the larger of the convoys already close to the island's capital, Cebu City, midway up the east coast. Shortly after dawn the Japanese in this convoy landed at Cebu City; at about the same time the men in the other convoy came ashore in the vicinity of Toledo, on the opposite side of the island.14

Defending the capital, where Kawaguchi had landed the bulk of his troops, was the Cebu Military Police Regiment of about 1,100 men under the command of Lt. Col.

[503]

[504]

Howard J. Edmands. Edmands' mission, like that of other unit commanders on the island, was to hold only long enough to allow the demolition teams to complete their work, then fall back into the hills. "I had no idea of being able to stop the Japs," explained General Chynoweth, "but I thought we could spend two or three days in withdrawal."15

The fight for Cebu City lasted only one day. Faced by a foe superior in numbers and weapons, the defenders fell back slowly, fighting for the time needed to block the roads and destroy the bridges leading into the interior. By the afternoon the fight had reached the outskirts of the city and at 1700 the Japanese broke off the action. Under cover of darkness Edmands pulled his men back to previously selected positions about ten miles inland, along a ridge which commanded the approaches from Cebu City to the central mountain area. Though the Japanese were in undisputed control of the capital at the end of the day, Edmands had achieved his purpose. He had gained the time needed by the demolition teams, and his regiment was still intact and withdrawing in good order.

The Japanese enjoyed equal success that day on the west side of the island, in the neighborhood of Toledo. Western terminus of the cross-island highway, that town was an important military objective. But, on the assumption that the narrow channel along the west would discourage an enemy from landing there, only a small force, the 3d Battalion, 82d Infantry (PA), had been placed in that area. The Philippine Army battalion opposed the enemy landing vigorously but without success and finally fell back along the cross-island highway toward the town of Cantabaco, leaving the Japanese in possession of Toledo.

At Cantabaco, midway across the island, the highway split in two. One branch turned northeast to pass close to Camp X, where General Chynoweth had his headquarters, then southeast to Talisay. The southern branch led into Naga. At both places there was a defending force of Filipinos whose route of withdrawal depended upon the security of Cantabaco. Should the Japanese pursuing the 3d Battalion, 82d Infantry, gain control of that town, the defenders would be cut off.

General Chynoweth appreciated fully the importance of Cantabaco to the defense of Cebu. Even before the Japanese landings, in anticipation of difficulty there, he had brought Colonel Grimes and his 3d Battalion, 83d Infantry, from Bohol to support the defenses of western Cebu. Now, on the afternoon of the 10th, he ordered Grimes to cover Cantabaco, and as an added precaution sent a messenger with orders to his reserve battalion in the north to move down to the threatened area. Grimes, "eager to get into the fray . . . started out with a gleam in his eye," and Chynoweth, confident that he had things reasonably well in hand, settled down for a good night's sleep.16

He got little rest that night. Time and again he was awakened by anxious staff officers who reported that the enemy was approaching from the direction of Cantabaco. Despite these reports Chynoweth remained confident. He had received no message from Grimes, and he felt sure that if the enemy had broken through at Cantabaco, Grimes would have sent word. Moreover, there had been no explosions to indicate that the demolition teams along the road were doing their work. He had in-

[505]

spected these demolitions himself and felt sure that if the enemy had passed Cantabaco, the charges would have been set off. But at 0330, when the sounds of battle became louder, Chynoweth's confidence began to wane. The enemy was undoubtedly nearing Camp X. A half hour later all doubts vanished when large groups of Filipinos, the outposts of Camp X, appeared in camp. They seemed hypnotized, fired in the air, and refused to obey commands in their haste to flee. After a brief conference with his staff, Chynoweth decided to pull back to an alternate command post on a ridge a half mile to the north and await developments there.

The collapse of the Cantabaco position had been the result of an unfortunate and unforeseen combination of events. The demolition teams in which Chynoweth had placed so much faith had waited too long and when the enemy appeared, led by tanks or armored cars, they had fled. Like his commander, Colonel Grimes believed that the enemy would be halted by blown bridges and obstacles along the road. Not hearing the sound of explosions, he, too, concluded that the Japanese were still at a safe distance. In his confidence he drove forward to familiarize himself with the terrain and was captured by an enemy patrol. Deprived of their commander, his men "stayed quite well hidden."17 So well were they hidden that even the Japanese were unaware of their presence.

The reserve battalion had never even started south. The messengers sent to that battalion failed to return, and if the battalion commander did receive Chynoweth's order to move to Cantabaco, he never complied with it. Instead, the battalion moved farther north, well out of reach of the enemy.

Opposed only by the retreating 3d Battalion, 82d Infantry, which was quickly dispersed, the Japanese had advanced swiftly from Toledo through Cantabaco and then along the Talisay and Naga roads. It was the Japanese force along the Talisay road that had scattered the Camp X outposts and forced upon Chynoweth the realization that his plans for the defenses of Cantabaco had miscarried.

With the enemy in possession of the cross-island highway, the fight for Cebu was over. Nothing more could be accomplished in central Cebu and on the night of the 12th, Chynoweth, with about 200 men, started north to his retreat in the mountains. From there he hoped to organize the few units still remaining on the island into an efficient guerrilla force. The Japanese did not claim the complete subjugation of the island until 19 April, but Wainwright had already conceded the loss of Cebu three days earlier when he ordered General Sharp to re-establish the Visayan-Mindanao Force and take command of the remaining garrisons in the Visayas.18

The Seizure of Panay

When General Chynoweth, the first commander of the Panay garrison, assumed command of the Visayan Force and moved to Cebu in mid-March, he had named as successor Colonel Christie, his chief of staff. Under Christie's leadership work on the island's defenses continued and by mid-

[506]

April preparations for the expected Japanese attack had been virtually completed.19

As on Cebu the plan of defense provided only for delaying action to allow the demolition teams to complete their work. The 61st Division (PA) and other troops on the islands, altogether 7,000 men, were to fall back to previously selected positions until they reached the mountains to the north. From there, well provided with the food and supplies gathered as a result of Operation Baus Au, Christie would wage guerrilla warfare against the enemy until such time as reinforcements arrived.

The enemy landing came at dawn, 16 April, and was made by the Kawamura Detachment of 4,160 men. The bulk of General Kawamura's troops came ashore at Iloilo, at the southeast corner of Panay, and a smaller force landed at Capiz to the north. Two days later a third landing was made at San Jose, along the southwest coast.20 None of the landings was opposed. By 20 April General Kawamura had occupied the strategic points of the island, and so far as he was concerned the campaign was over.

For Colonel Christie, safe in his well-stocked mountain retreat, the campaign had just begun. Wild game was plentiful; he had ample fresh water, 500 head of cattle, 15,000 bags of rice, hundreds of cases of canned goods, and an adequate supply of fuel. Machine shops had been constructed in the mountains, and when his supply of rice gave out there was a mill to thresh more. Almost immediately he began to send his men out on hit-and-run raids. These so aroused the Japanese that they organized a punitive expedition at San Jose to capture Christie and destroy his headquarters. A Filipino agent sent warning of the Japanese plans and an ambush was prepared by a company of men armed only with bows and arrows, spears and bolos. Hidden along the sides of the pass leading to Christie's hideout, the Filipinos with their primitive weapons took the Japanese completely by surprise, killed many, and sent the rest posthaste back to San Jose. But the successes of guerrilla warfare could not disguise the fact that, with the principal towns and road net in their hands, the Japanese controlled the island.

By the seizure of Cebu and Panay, the Japanese had secured a firm grip on the most important islands in the Visayas. The forces still holding out on Negros, Samar, Leyte, and Bohol were considerably smaller than those already defeated and driven back into the hills, and the Japanese were confident that these islands could be occupied at will. By 20 April the campaign for the Visayas was, for all practical purposes, at an end, and General Homma was free to send the Kawaguchi and Kawamura Detachments against Mindanao.

The Japanese force that landed at Davao on 20 December had been a small one. It had consisted of two groups, one of which, the Sakaguchi Detachment, left soon after for Jolo Island and the Netherlands Indies. The other group, led by Lt. Col. Toshio Miura and consisting of the 1st Battalion,

[507]

33d Infantry, plus miscellaneous troops, had remained on Mindanao.21 Time and again Colonel Miura had attempted to extend his control into the interior but without success. Indeed, had he not had air and artillery support and had his men not been equipped with automatic weapons, it is doubtful if he could have remained on the island.

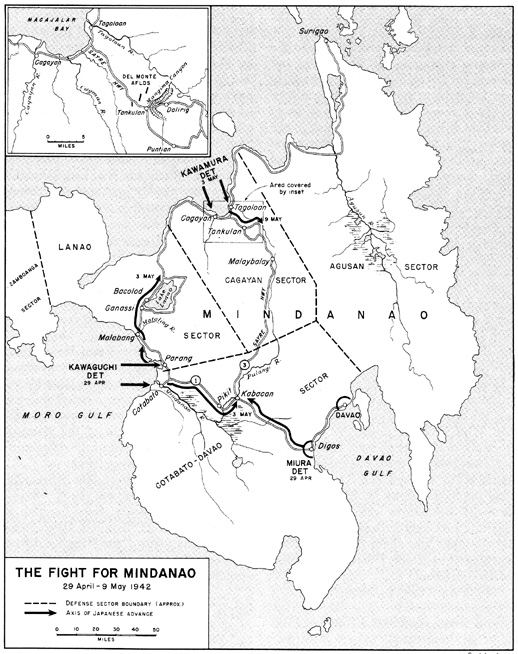

Since General Sharp's arrival on Mindanao early in January much had been done to prepare the island's defenses. With the additional troops transferred from the Visayas, Sharp had organized the island into five defensive sectors: the Zamboanga Sector; the Lanao Sector, in the northwest; the Cagayan Sector, in the north-central portion of the island; the Agusan Sector, in the east; and the Cotabato-Davao Sector in the central and south portion of the island. The last was the largest of the sectors and was divided into three subsectors: Digos, Cotabato, and Carmen Ferry. To each sector was assigned a force of appropriate size whose commander reported directly to Mindanao Force headquarters at Del Monte, ten miles inland from the northern terminus of the Sayre Highway and adjacent to the Del Monte Airfield. (Map 24)

Despite occasional flurries along the Digos and Agusan fronts and, in March, some action in Zamboanga, which the Japanese occupied early that month, the troops on Mindanao continued their training.22 Individual and unit training continued at a steady pace and was supplemented by special instruction at a school in infantry tactics in central Mindanao. The school was staffed by Philippine Scouts of the 43d Infantry.23

The greatest drawback to the training program was the shortage of ammunition. The supply was so limited that its expenditure on the firing range was prohibited. Instead, the men spent long hours in simulated fire, with doubtful results. "A few rounds fired by the soldier," observed Colonel Tarkington, "would have demonstrated to him the capability of his weapon, acquainted him with its recoil, and paid dividends in steadier marksmanship."24 Most of the men who fought on Mindanao never fired a live round before they went into battle.

While General Sharp sought to strengthen the defenses of Mindanao, the Japanese completed their plans for the seizure of the island. The plan finally adopted provided for a co-ordinated attack from three directions by separate forces toward a common center, followed by a quick mop-up of the troops in the outlying portions of the island. One of these forces, the Miura Detachment, was already on the island, on garrison duty at Davao and Digos, a short distance to the south. It was to be relieved by a battalion of the 10th Independent Garrison and then strike out from Digos toward the Sayre Highway. Its route of advance would be northwest along Route 1, which intersected

[508]

MAP 24

[509]

the Sayre Highway about midway across the island.

The other two forces committed to the Mindanao operation, the Kawaguchi and Kawamura Detachments, would have to make amphibious assaults. Each would be relieved of responsibility for the security of the island it had occupied, embark in the waiting transports, and sail under naval escort by divergent routes to its designated target. General Kawaguchi was to take his men ashore at Cotabato midway along the west coast, at the mouth of the Mindanao River. From Cotabato, which was joined to Route 1 by a five-mile stretch of highway, he would send part of his force east toward the Sayre Highway to meet Colonel Miura's troops marching west. The rest of the detachment was to land at Parang, about twelve miles north of Cotabato, and push north along Route 1, past Lake Lanao, then east along the island's north shore to join with the Kawamura Detachment.

Kawamura was to come ashore in northern Mindanao at the head of Macajalar Bay, the starting point of the Sayre Highway. While a small portion of his force struck out to the west to meet Kawaguchi's men, the bulk of the detachment would march south through central Mindanao, along the Sayre Highway. Ultimately, elements of the three detachments-one marching east, another west, and the third south-would join along the Digos-Cotabato stretch of Route 1 across the narrow waist of the island.25

Late in April three battalions of the 10th Independent Garrison took over garrison duty on Mindanao, Cebu, and Panay. Colonel Miura immediately moved south from Davao to Digos to prepare for his advance along Route 1, while Kawamura and Kawaguchi began to embark their troops for the coming invasion. First to sail was the Kawaguchi Detachment which left Cebu on 26 April in six transports escorted by two destroyers. Kawamura's departure from Panay came five days later and brought him to Macajalar Bay as Kawaguchi's troops were fighting their way northward to greet him. Wainwright's order to Sharp on 30 April, to hold all or as much of Mindanao as possible with the forces he had, found that commander already engaged with the enemy on two fronts.26

The Cotabato-Davao Sector

Early on the morning of 29 April, the emperor's birthday, the Kawaguchi Detachment began to land at Cotabato and Parang, midway up the west coast of Mindanao.27 The seizure of both towns was vital to Kawaguchi's plan. From Cotabato he could advance inland to the Sayre Highway by way of Route 1 or in small boats by way of the Mindanao River. From Parang he could send his men north toward Lake Lanao and the north coast of the island, or southeast to join the rest of the detachment heading toward the Sayre Highway.

Defending Cotabato and the surrounding area were troops of the 101st Division (PA)-101st Infantry (less 1st and 3d Battalions), the 2d Battalion, 104th Infantry, and a battalion of the 101st Field Artillery, organized and equipped as infantry-strengthened by Constabulary troops and

[510]

service units. This entire force was under Lt. Col. Russell J. Nelson, the Cotabato Subsector commander. Half of his men he had placed in and around the town; the rest were posted farther inland covering Route 1 and the Mindanao River.

The men of the Kawaguchi Detachment encountered little resistance getting ashore at Cotabato, where the demolition teams had already completed their work. Their advance through the town, however, proved more difficult. There they were opposed by the 2d Battalion, 104th Infantry, which put up a stubborn resistance until enemy aircraft, presumably from Zamboanga, entered the fight. The battalion then pulled back to a previously prepared position on the outskirts of Cotabato where it prepared for an extended stand.28 Events beyond its control made this impossible.

Earlier in the day a portion of the Japanese force which had landed near Parang began to push southeast toward the junction of Route 1 and the Cotabato road. At about 1530 these Japanese made contact with the 3d Battalion, 102d Infantry, which was defending the north flank of the Cotabato force. In the engagement that followed, the Filipinos held firm for more than three hours, but finally, at 1900, broke contact and withdrew along Route 1, leaving the road to Cotabato open. The position of the 2d Battalion, 104th Infantry, which had resisted the Japanese advance through the town earlier in the day, was now untenable. In danger of being cut off and taken from the rear, the battalion reluctantly abandoned its position on the outskirts of Cotabato and pulled back through the road junction to Route 1.

The next day, 30 April, General Kawaguchi began his advance eastward toward the Sayre Highway and a meeting with Colonel Miura's troops. Most of his troops moved overland by way of Route 1, but Kawaguchi did not neglect the water route offered by the Mindanao River. Three hundred of his men in armored barges took this route, which paralleled Route 1 and from which the water-borne troops could easily reach that road by trail. Both advances were supported by aircraft.

There was little action during the day. Colonel Nelson, the sector commander, received reports on the progress of the two Japanese columns but was most concerned about the troops sailing up the river. There was nothing to prevent this force from disembarking along the river bank and moving up one or more of the numerous trails to Route 1 to establish a roadblock behind Nelson's retreating men. Before the day was over, Nelson was receiving reports of just such movements, as well as the presence of Japanese troops in Pikit, where the Mindanao River crossed Route 1 at a point only about eight miles from the Sayre Highway.

The report that Japanese troops were in Pikit was even more disquieting to Colonel Nelson than the reports of hostile landings along the banks of the Mindanao River. If true, his force was already cut off. He decided therefore to move his men away from the road and onto the trails leading north. By doing so he left himself free to

[511]

accomplish his principal mission, which was to protect the routes north of Route 1. The decision made, he ordered the destruction of roads and bridges and placed small covering forces along the main trails to cover his withdrawal. There was nothing to prevent Kawaguchi now from consolidating his control of the entire stretch of Route 1 from Cotabato to Pikit.

Kawaguchi's rapid advance eastward toward the Sayre Highway, which intersected Route 1 at Kabacan, eight miles east of Pikit, placed him in an excellent position to cut off the escape route of the troops in the Digos Subsector. These troops, who were retreating westward along Route 1 before the Miura Detachment, would have to pass through Kabacan before they could make their way north along the Sayre Highway. If Kawaguchi could reach Kabacan ahead of the Filipinos, he might not only cut them off but take them from the rear. Indeed, the Japanese appear to have anticipated this possibility and Colonel Miura's orders were to keep the Digos force engaged long enough to allow Kawaguchi to reach Kabacan.29

The Digos force had been under pressure since the middle of April. Led by Lt. Col. Reed Graves, this force consisted of the 101st Field Artillery (PA), less one battalion, and the 2d Battalion, 102d Infantry (PA). By the 28th of the month, after a particularly heavy attack, it was clear to Colonel Graves that the Japanese on his front were about to make a major effort. The next morning, simultaneously with the landing of the Kawaguchi Detachment at Cotabato, Colonel Miura began his advance westward toward the Sayre Highway, supported by low-flying aircraft from Davao. Graves's troops opposed the Japanese advance stubbornly, and effectively broke up the initial assault with mortar fire.

Action during the next two days was indecisive, and consisted largely of air attacks and patrol actions. On 2 May, Colonel Miura again launched a full-scale attack. This time he opened with a four-hour artillery and mortar preparation supplemented by the strafing attacks of seven dive bombers. When the infantry moved out at 1300 it had the support of three tanks. Again the Japanese were halted and the fight ended at 1700 with a victory for the Filipinos.

Graves's brave stand proved a fruitless gesture, for two hours later, at 1900 of the 2d, he was ordered to withdraw immediately toward the Sayre Highway. The order came from the commander of the Cotabato-Davao Sector, Brig. Gen. Joseph P. Vachon, who had sent a small force to Kabacan to delay the Japanese approaching from the west. The Digos force would have to make good its escape while there was still time. Further resistance, no matter how successful, would only increase the peril to Colonel Graves and his men. That night they began to evacuate the position they had held so stubbornly since 28 April. Next day, with the 2d Battalion, 102d Infantry, acting as rear guard, the Digos force began to march toward Kabacan and the Sayre Highway.

Kabacan now became the focal point of the fight in the Cotabato-Davao Sector. General Vachon was determined to hold the southern terminus of the Sayre Highway as long as possible and placed all the troops he could muster there. In addition to the force he had already sent to delay Kawaguchi's march eastward from Pikit, he di-

[512]

rected Colonel Graves and the troops of the Carmen Ferry Subsector to hold the Sayre Highway. The Kawaguchi Detachment successfully fought its way to Kabacan, but arrived too late to close the trap on the Digos force. All Kawaguchi's efforts to clear the Sayre Highway and make his way northward failed. Vachon's troops held firm until the end of the campaign a week later.

Those of General Kawaguchi's men who came ashore at Parang on the morning of 29 April met an entirely different reception from that which greeted the men landing at Cotabato. Here they were met at the beaches by the regulars of the 2d Infantry, 1st Division (PA).30 Under the leadership of Col. Calixto Duque, the Filipinos had established strong defensive positions on the beach and when the first hostile landing parties made their appearance at 0400 of the 29th they ran into heavy and effective fire from machine guns.

For more than six hours, until 1100, the 2d Infantry held its ground. Finally, in danger of being outflanked by a Japanese force that had landed a short distance to the south, the regiment fell back to a previously prepared position about two miles inland.31 After sending a small detachment southward to establish contact with the force landing at Cotabato, Kawaguchi's men moved into the town. By late afternoon they had established contact with the southern force and were in firm possession of Parang. Their next objective was the coastal town of Malabang, twenty-two miles to the northwest.

Guarding Malabang was the 61st Infantry (PA), led by Col. Eugene H. Mitchell. Alerted by the landings to the south, Mitchell had ordered his demolition teams to stand by and sent his men into their previously prepared positions along the west bank of the Mataling River, just above the town. In Malabang, guarding the trail which led northwest out of the town past the right flank of the Mataling line, was the 3d Battalion's Company K. To the rear were two 2.95-inch mountain guns, manned by men of the 81st Field Artillery (PA).

Rather than march his men along the twenty-two mile stretch of Route 1 which separated Parang and Malabang, General Kawaguchi apparently decided to utilize the transports which had brought them to Mindanao. Leaving a small detachment to guard the town, he sent his troops back to the ships late on the night of the 29th and set sail for Malabang. At about 0300 of the 30th, at a point a few miles south of the objective, the Japanese began to land.32 A half hour later Company K, 61st Infantry, reported that enemy light tanks had passed its position.

Action along the Mataling line opened at dawn. Within a few hours, after suffering heavy casualties, the Filipinos were forced to give way on the left. In danger of having his flank turned, Colonel Mitchell reinforced the left but was unable to regain the ground lost. Finally, at 1400, he ordered the right battalion to attack in the hope that he could

[513]

thus relieve the pressure on the left. The attack, though it gained some ground, failed in its objective, for the Japanese had brought more troops as well as artillery into position before the Mataling line.

The diversionary attack having failed, Colonel Mitchell decided to place his entire force in the threatened area. To do this he had to abandon the right portion of the line and call in his reserve. It was a gamble but his only alternative was to give up the Mataling line entirely. Orders for the attack went out late on the afternoon of the 30th, just before the Japanese attacked again. Advance elements of the reserve battalion arrived in time to participate in the fight that followed, but the right battalion never received its orders, and at 2000 Colonel Mitchell was forced to abandon the Mataling line.

The route of withdrawal was along Route 1. With one company as rear guard, the right and reserve battalions withdrew in an orderly fashion to a new position four miles to the north. The left battalion, unable to use Route 1, withdrew by a circuitous route along a back trail and did not join the rest of the regiment until the next afternoon. Save for patrol and rear guard action there was no fighting that night.

The Japanese attacked Colonel Mitchell's new position at 0730 the next day, 1 May. Again they struck at the flank of the Filipino line and at 1030 Mitchell was forced to order a second withdrawal. This time he fell back five miles. In the confusion one company was cut off, but Colonel Mitchell was compensated for this loss by the addition of two companies of the 1st Battalion of the 84th Provisional Infantry Regiment, which joined him when he reached his new position. Later in the day the 120 survivors of the battalion which had withdrawn from the Mataling line along a back trail straggled into camp, and with this force Colonel Mitchell began to prepare for the next attack. His orders from the sector commander, Brig. Gen. Guy O. Fort, were to hold his position at all cost.

The Japanese, who had lost contact with the retreating Filipinos during the morning, reached the new line at about 1300. While their infantry prepared for the attack, they kept the Filipinos pinned down with artillery, mortar, and machine gun fire. At dusk, the volume of Japanese fire increased and, shortly after, the infantry moved out in a full-scale attack. Within a short time they had overrun Colonel Mitchell's defenses and were threatening his command post. By 2300, when the Japanese called off the attack, the defending force had practically disappeared.

Rounding up all the men he could find, altogether about thirty, Mitchell made his way to the rear. At about 0230 he encountered a detachment of sixty men from the 81st Division (PA) on the road and began to establish a holding position. The men had just set to work when they were struck by a Japanese motorized column which scattered the tired and dispirited men. Colonel Mitchell's luck had run out. Twice he had escaped the Japanese, but this time he was captured. With the rout of the 61st Infantry and the capture of its commander, the Japanese gained control of all of Route 1 as far north as Lake Lanao.

Only one regiment of the Lanao force, Lt. Col. Robert H. Vesey's 73d Infantry (PA), was still intact. With two battalions in the vicinity of Lake Lanao and the third on beach defense to the north, this regiment stood directly in the path of Kawaguchi's advance. At the first news that the enemy was approaching, Colonel Vesey set out for

[514]

Ganassi at the southwest corner of the lake to meet him. Here a secondary road branched off to circle the east shore while Route 1 continued northward along the west side of the lake. By holding this town, Vesey believed, he could prevent the Japanese from gaining access to either road. A preliminary skirmish at Ganassi on the morning of 2 May convinced him that the town was not defensible and that afternoon he withdrew to Bacolod on the west shore of Lake Lanao to make his stand. The Japanese promptly sent a small force along the east road, but it presented no immediate threat to the defenders at Bacolod.

The line finally established at Bacolod by Colonel Vesey extended from Lake Lanao across Route 1 and was held by the two battalions of the 73d Infantry reinforced with stragglers from the 61st Infantry. Along the front was a narrow stream which flowed under a bridge across Route 1 to empty into the lake. As an added precaution, the bridge was destroyed as soon as the troops were in position. Additional protection was afforded the troops on the far side of the stream, opposite the demolished bridge, by a 2.95-inch mountain gun.

The Japanese who had reached Ganassi early on the morning of 2 May had halted to await the arrival of the rest of the force which moved up during the day. Early the next morning the entire force, with light tanks in the lead, advanced north along Route 1. By 0800 the tanks had reached the destroyed bridge in front of the 73d Infantry line and halted. One tank sought to cross the shallow stream but was hit by a shell from the 2.95-inch mountain gun and knocked out. The others made no further effort to cross. With Route 1 blocked, the rest of the Japanese column came to an abrupt halt and the troops poured out of the trucks. Before they could deploy and take cover, they were hit by withering fire from the far side of the stream, "which made up in its concentration at point-blank range what it lacked in accuracy."33 The toll on the Japanese side was heavy.

Despite this first setback the men of the Kawaguchi Detachment continued to press forward. Soon they had the support of artillery and a single plane, which alternately attacked and observed the 73d Infantry position. Unable to make any headway by frontal assault, the Japanese sought to turn the enemy's flanks. Their efforts proved successful before the morning was out and shortly after noon Colonel Vesey gave the order to withdraw.

The record of the 73d Infantry for the rest of that day, 3 May, is one of successive withdrawals. Each time Colonel Vesey put his two battalions into position, the Japanese broke through. So closely did the enemy motorized column pursue the Filipinos that they scarcely had time to organize their defenses. By midnight Vesey had taken his men back in the hills north of Lake Lanao, where he paused to reorganize his scattered forces. The Japanese made no effort to follow. The victory was theirs and the road along the north shore lay open.

Between 29 April and 3 May, General Kawaguchi with a force of 4,852 men and some assistance from the Miura Detachment had gained control of southern and western Mindanao. Only in the north, in the Cagayan Sector, were the Filipinos still strong enough to offer organized resistance. But already on the morning of 3 May, the third of the forces General Homma had as-

[515]

signed to the Mindanao operation, the Kawamura Detachment, had begun to land along the shore of Macajalar Bay.

The Cagayan Sector

In the critical Cagayan Sector, which included the northern terminus of the Sayre Highway and the vital Del Monte Airfield, General Sharp had the Mindanao Force reserve, none of which had yet been committed, and the 102d Division (PA). This division, formed from existing and provisional units after the outbreak of war, consisted of the 61st and 81st Field Artillery, organized and equipped as infantry, and the 103d Infantry. Col. William P. Morse, the division and sector commander, believing that an attack in his sector would most likely come from the sea and have for its objective the seizure of the Sayre Highway, had posted his troops along Macajalar Bay, between the Tagoloan and Cagayan Rivers. Holding the four miles of coast line from the Tagoloan west to the Sayre Highway was Lt. Col. John P. Woodbridge's 81st Field Artillery and a 65-man detachment from the 30th Bomb Squadron (US). The stretch of coast line from the highway to the Cugman River, equal in length to that held by Colonel Woodbridge, was defended by the 61st Field Artillery under Col. Hiram W. Tarkington. On the left (west), extending the line to the Cagayan River, was Maj. Joseph R. Webb's 103d Infantry.34

First warning of the approach of the enemy reached General Sharp's headquarters on the afternoon of 2 May when a reconnaissance plane sighted the convoy carrying the Kawamura Detachment north of Macajalar Bay. The troops on beach defense were immediately alerted, and that night, after the convoy had entered the bay, the demolition plan was put into effect. Shortly after, about 0100 of the 3d, the Japanese troops began coming ashore at both extremities of the line, at Cagayan and at the mouth of the Tagoloan River. Supported by fire from two destroyers offshore, the Japanese by dawn had secured a firm hold of the beach line between the Tagoloan and the Sayre Highway.

Those of Kawamura's men who came ashore in the vicinity of Cagayan met a warm reception. Unable to prevent the enemy from landing, Major Webb attacked the beachhead with two companies. So successful was the attack that only the withdrawal of the 61st Field Artillery on his right prevented him, Webb believed, from driving the enemy back into the sea. With his right flank exposed, Webb was forced to break off the engagement and pull his men back.

Meanwhile General Sharp had sent additional troops to hold the Sayre Highway. Up until now he had refused to commit his reserve. But with half of Mindanao in enemy hands and with the Japanese landing more troops within a dozen miles of his headquarters, he decided that the time had come to throw all available troops into the fight. Closest to the scene of action was a detach-

[516]

ment under Maj. Paul D. Phillips, armed with three 2.95-inch guns, all that remained of the artillery in the Mindanao Force. Farther to the rear were the 62d and 93d Infantry (PA). Sharp ordered all three units to move up to the line. Pending the arrival of the two regiments, Phillips' detachment was to take up a position behind a deep crater on the Sayre Highway and block any Japanese attempt to advance south. When it was joined later in the day by the 62d and 93d Infantry Sharp would have a strong line, supported by artillery, in the path of the Japanese.

Major Phillips' detachment had hardly set up its guns when, at 0730, it came under fire from the Japanese advancing along the Sayre Highway. In the initial attack the detachment was forced back about 700 yards. Fortunately, the Japanese failed to press their advantage and Phillips was able to organize another holding position at his new location. He was joined here early in the afternoon by advance elements of the 93d Infantry; the rest of that regiment when it reached the area prepared a second position a short distance to the south. The 62d Infantry, whose assembly area was farther south on the Sayre Highway, failed to join the other two units that day.

To General Sharp "events seemed to be moving satisfactorily."35 Although the enemy controlled the beaches and the northern terminus of the Sayre Highway, his own troops had disengaged without loss and were in position along a secondary line of defense. Already part of his reserves were blocking the highway and other troops were moving up to their support. So optimistic was the general that he set his staff to work on a plan to counterattack north along the highway next morning.

The optimism at force headquarters was quickly dissipated when reports of Japanese progress during the day began to come in. The enemy, it was learned, had pushed back the 61st and 81st Field Artillery. The 103d Infantry had resisted more stoutly but was also falling back and in danger of being outflanked. General Sharp's hopes for a counterattack were dealt the final blow when, at 1600, Colonel Morse ordered a general withdrawal to defensive positions astride the Sayre Highway, about six miles south of the beach. The move was to be made that night under cover of darkness.

Before this plan could be put into effect it was changed by General Sharp, who, after a conference with Morse, Woodbridge, and Webb, decided to establish his next line even farther south than the line already selected. The position selected paralleled the Mangima Canyon, a formidable natural barrier east of the town of Tankulan, and the Mangima River. At Tankulan the Sayre Highway splits, one branch continuing south then east, the other east then south. Before the two join, eight air miles east of Tankulan, they form a rough circle bisected from north to south by the Mangima Canyon and River. East of the junction of the canyon and the upper road lies the town of Dalirig; to the south the river cuts across the lower road before Puntian. Possession of these two towns would enable the defenders to block all movement down the Sayre Highway to central Mindanao.

At 2300, 3 May, General Sharp issued orders for the withdrawal to the Mangima line. The right (north) half of the line, the Dalirig Sector, was to be held by the 102d Division which had been reorganized and now consisted of the 62d Infantry, the 81st Field Artillery, the 2.95-inch gun detachment, and the two Philippine Scout com-

[517]

panies of the 43d Infantry from force reserve. The Puntian Sector would be held by the 61st Field Artillery and the 93d Infantry. Colonel Morse would command the troops in Dalirig; Col. William F. Dalton, those before Puntian. The 103d Infantry, cut off by the Japanese advance was made a separate force and assigned the mission of defending the Cagayan River valley.

The withdrawal was completed on the morning of 4 May when all units reached their designated positions. The remainder of that day as well as the next, during which time the Japanese limited themselves to aerial reconnaissance and bombardment, was spent in organizing the line. In the Dalirig Sector, Lt. Col. Alien Thayer's 62d Infantry, closely supported by the 2.95-inch gun detachment, occupied the main line of resistance along the east wall of Mangima Canyon. Companies C and E, 43d Infantry (PS), Colonel Morse's reserve, were stationed in Dalirig, and in a draw 500 yards behind the town were the 200 men of the 81st Field Artillery, which had had a strength of 1,000 when the Japanese landed. Colonel Dalton, with two regiments, used the lull in battle similarly to dig in before Puntian.

On the morning of 6 May the Japanese resumed the attack. Their approach toward Tankulan was reported by patrols of the 62d Infantry which for the past two days had moved freely in and around the town. During the morning advance elements of the Kawamura Detachment passed through Tankulan and began to advance along the upper road toward Dalirig. Late that afternoon the Japanese moved into Tankulan in force and began to register their artillery on Dalirig.

There was little action the next day. Japanese artillery, well out of range of Major Phillips' 2.95-inch guns, dropped their shells accurately into the 62d Infantry line while their aircraft bombed and strafed gun positions and troops. The left battalion suffered most from the bombardment and Colonel Thayer finally had to send in his reserve battalion to bolster the line.

The artillery and air attacks continued until the evening of the 8th when, at 1900, General Kawamura sent his infantry into action. In the darkness many of the Japanese were able to infiltrate the Filipino line where they created considerable confusion. During the height of the confusion two platoons mysteriously received orders to withdraw and promptly pulled out of the line. Their march to the rear came as a complete surprise to company, battalion, and regimental headquarters, none of which had issued the order. The two platoons were quickly halted, but before they could return to the front they were attacked by a small force of Japanese infiltrators. Other 62d Infantry troops joined the fight but in the darkness it was impossible to distinguish between friend and foe. It was only after the personal intervention of Colonel Thayer that the Filipinos, whose fire was doing more to panic the men on the line than the efforts of the enemy, were persuaded to cease fire.

The action continued through the night of 8-9 May. The 62d Infantry held on as long as possible but by morning the tired and disorganized Filipinos had been pushed off the main line of resistance and were falling back on Dalirig. Already the 2.95-inch gun detachment had pulled out, leaving only the two Scout companies of the 43d Infantry to face the enemy.

In the Puntian Sector the Japanese were content to keep Colonel Dalton's troops in place by artillery fire. Until the night of 8-9

[518]

May, Dalton had been able to maintain contact with the 62d Infantry on his right (north) but during the confusion which marked the fighting that night he lost contact. In an effort to relieve the pressure on Thayer's regiment he launched his own attack the next morning. Though the attack was successful it failed to achieve its purpose, for the disorganized 62d Infantry was already in full retreat.

Undeterred by Colonel Dalton's gains in front of Puntian, General Kawamura continued to press his advantage in the north. At about 1130 of the 9th, as the 62d Infantry began to withdraw through Dalirig, his men entered the town from three sides and struck the retreating Filipinos. Already disorganized, the troops of the 62d Infantry scattered in all directions. The two Scout companies in the town, under the leadership of Maj. Alien L. Peck, made a brave stand but finally withdrew just before their positions were encircled.

The escape route of the fleeing troops lay over flat, open country, devoid of cover. Pursued by small-arms and artillery fire and strafed by low-flying aircraft, the retreating units lost all semblance of organization. Each man sought whatever protection he could find, discarding his equipment when it impeded his progress. What had begun as a withdrawal ended in a complete rout, and by the end of the day the Dalirig force had virtually ceased to exist. Except for 150 survivors of the 2.95-inch gun detachment in position five miles east of Dalirig, the upper branch of the Sayre Highway lay open to the invaders.

Along the southern branch of the highway Colonel Dalton and his two regiments still held firm at Puntian. But already Kawamura was sending additional troops to this sector and increasing the pressure against the Puntian force. Whether Dalton would be able to hold was doubtful, but even if he did his position was untenable. The enemy could sweep around his north flank from the direction of Dalirig or take him from the rear by continuing along the upper road to its junction with the lower road, then turning back toward Puntian. There was no way out.

Whatever consolation General Sharp derived from the fact that the Puntian force was still intact was tempered by the bitter realization that the Mangima line had been breached and the bulk of his force destroyed. "North front in full retreat," he radioed General MacArthur. "Enemy comes through right flank. Nothing further can be done. May sign off any time now."36 Except for the resistance of scattered units, the Japanese campaign in Mindanao was over.

[519]

Return to Table of Contents

Return to Chapter XXVII |

Go to Chapter XXIX |

Last updated 1 June 2006 |