CHAPTER XXVI

Surrender

When, late in the evening of 8 April, General Wainwright ordered a counterattack by I Corps in the direction of Olongapo, General King had already reached the conclusion that he had no alternative but to surrender. By that time all chance of halting the Japanese advance, much less launching a successful counterattack, was gone. The last of his reserves as well as those of the two corps had been committed. On the left, I Corps was still intact but was in the process of withdrawal in an effort to tie in its right flank with the rapidly crumbling II Corps. General Parker's corps on the right had completely disintegrated and no longer existed as a fighting force. Efforts to hold at the Alangan River had failed and General Bluemel had reported soon after dark that his small force of 1,300 Scouts and Americans was in retreat. The Provisional Coast Artillery Brigade (AA) had been ordered to destroy its antiaircraft equipment and form as infantry along the high ground just south of the Cabcaben airfield, near the southern tip of the peninsula. On the night of 8 April this unit formed the only line between the enemy and the supply and service elements around Cabcaben and Mariveles. "II Corps as a tactical unit," wrote King's G-3, "no longer existed."1

The deterioration of the line in the II Corps sector gave the enemy free passage to the south where the hospitals with their 12,000 defenseless patients, already within reach of Japanese light artillery, were located. Philippine Army troops were in complete rout and units were melting away "lock, stock, and barrel." Headquarters had lost contact with the front-line troops and could no longer control the action except through runners or the armored vehicles of the SPM battalion. The roads were jammed with soldiers who had abandoned arms and equipment in their frantic haste to escape from the advancing Japanese infantry and armored columns and the strafing planes overhead. "Thousands poured out of the jungle," wrote one observer, "like small spring freshets pouring into creeks which in turn poured into a river."2

Even if General King had been able at the last moment to muster enough arms and men to oppose the Japanese advance it is extremely doubtful that he could have averted or even delayed the final disaster, The men on Bataan were already defeated and had been for almost a week. Disease and starvation rather than military conditions had created the situation in which General King now found himself. The men who threw away their arms and equipment and jammed the roads and trails leading south were beaten men. Three months of malnutrition, malaria, and intestinal infections had left them weak and disease-ridden, totally incapable of the sustained

[454]

physical effort necessary for a successful defense.

General Wainwright was well aware of the disintegration of the Luzon Force. His messages to Marshall and MacArthur on the 8th gave a clear picture of impending doom. Late that night he had told MacArthur, "with deep regret," that the troops on Bataan were "fast folding up," and that the men were so weak from malnutrition "that they have no power of resistance."3 MacArthur, in turn, had alerted Washington to the danger. "In view of my intimate knowledge of the situation there," he warned the Chief of Staff, "I regard the situation as extremely critical and feel you should anticipate the possibility of disaster there very shortly."4 By the time this warning reached Washington silence had fallen on Bataan.

If the situation appeared critical to those on Corregidor and in Australia, how much blacker was the future to General King on whom rested the responsibility for the fate of the 78,000 men on Bataan. As early as the afternoon of 7 April, when the last of the Luzon Force and I Corps reserves had been committed without appreciably delaying the enemy, he had realized that his position was critical. It was then that he sent his chief of staff, General Funk, to Corregidor to inform Wainwright that the fall of Bataan was imminent and that he might have to surrender. Funk's face when he told Wainwright about the physical condition of the troops and the disintegration of the line, "was a map of the hopelessness of the Bataan situation."5 While he never actually stated during the course of his conversation with Wainwright that General King thought he might have to surrender, Funk left the USFIP commander with the impression that the visit was made "apparently with a view to obtaining my consent to capitulate."6

Though Wainwright shared King's feelings about the plight of the men on Bataan, his answer to Funk was of necessity based upon his own orders. On his desk was a message from MacArthur which prohibited surrender under any conditions. When Wainwright had written ten days earlier that if supplies did not reach him soon the troops on Bataan would be starved into submission, MacArthur had denied his authority to surrender and directed him "if food fail" to "prepare and execute an attack upon the enemy."7 To the Chief of Staff he had written that he was "utterly opposed, under any circumstances or conditions to the ultimate capitulation of this command. ... If it is to be destroyed it should be upon the actual field of battle taking full toll from the enemy."8

[455]

Wainwright was further limited in his reply to Funk by President Roosevelt's "no surrender" message of 9 February. This message, it will be recalled, had been given MacArthur at the time Quezon had made his proposal to neutralize the Philippines. On Wainwright's assumption of command a copy of the original text had been sent to him, with the statement that "the foregoing instructions from the President remain unchanged."9 In his reply to the President, Wainwright had promised "to keep our flag flying in the Philippines as long as an American soldier or an ounce of food and a round of ammunition remains."10

Under direct orders from the President and MacArthur "to continue the fight as long as there remains any possibility of resistance," Wainwright, therefore, had no recourse but to tell General Funk on the 7th that Bataan must be held. In the presence of his chief of staff he gave Funk two direct orders for General King: first, that under no circumstances would the Luzon Force surrender; and second, that General King was to counterattack in an effort to regain the main line of resistance from Bagac to Orion. "I had no discussion with General King," Wainwright later explained to MacArthur, "which might in any way have led him to believe, either that capitulation was contemplated, or that he had authority to send a flag of truce. On the contrary I had expressly forbidden such action. General King did not personally broach the subject of capitulation to me."11 When Funk left Wainwright's office with the orders to attack there were tears in his eyes. Both he and Wainwright knew what the outcome would be.12

While Wainwright's orders are understandable in terms of his own instructions, they placed General King in an impossible position. He was now under orders to launch a counterattack which he knew could not be carried out. If he could hold his position he might avert the necessity of surrender but even this proved impossible, as the events of the 7th and 8th showed. The only alternative remaining to King if he followed Wainwright's orders was to accept the wholesale slaughter of his men without achieving any military advantage. Under the circumstances, it was almost inevitable that he would disobey his orders.

Wainwright evidently appreciated King's position, and even expected him to surrender. Some years later, after his return from prison camp, he wrote: "I had my orders from MacArthur not to surrender on Bataan, and therefore I could not authorize King to do it." But General King, he added, "was on the ground and confronted by a situation in which he had either to surrender or have his people killed piecemeal. This would most certainly have happened to him within two or three days."13

[456]

At just what point in the last hectic days of the battle of Bataan General King made his decision is not clear. He may already have decided to surrender on the 7th when he sent Funk to Corregidor, for even at that time it was evident that defeat was inevitable. The next day, sometime during the afternoon, King instructed his senior commanders to make preparations for the destruction of all weapons and equipment, except motor vehicles and gasoline, but to wait for further orders before starting the actual destruction. At the same time he told General Wainwright that if he expected to move any troops from Bataan to Corregidor, he would have to do it that night "as it would be too late thereafter."14 When Colonels Constant Irwin and Carpenter came to Bataan to discuss the withdrawal of the 45th Infantry (PS) with the Luzon Force staff they "gained the impression" after a conversation with King that he felt the decision to surrender "might be forced upon" him.15

The inability of General Bluemel's force to hold the line at the Alangan River on the 8th must have been the deciding factor in General King's decision to surrender. He learned of Bluemel's predicament after dark when General Parker reported that the Alangan River position had been turned from the west and that all units were withdrawing. As a last desperate measure he ordered Colonel Sage's antiaircraft brigade to establish a line south of the Cabcaben airfield. By 2300 it was evident that it would be impossible to reinforce the last thin line, which was still forming, and that there was nothing to prevent the enemy from reaching the congested area to the south. It was at this time that General King held "a weighty, never to be forgotten conference" with his chief of staff and his operations officer.16

At this meeting General King reviewed the tactical situation very carefully with his two staff officers and considered all possible lines of action. Always the three men came back to the same problem: would the Japanese be able to reach the high ground north of Mariveles, from which they could dominate the southern tip of Bataan as well as Corregidor, as rapidly if the Luzon Force opposed them as they would if their advance was unopposed. The three men finally agreed that the Japanese would reach Mariveles by the evening of the next day, 9 April, no matter what course was followed. With no relief in sight and with no possible chance to delay the enemy, General King then decided to open negotiations with the Japanese for the conclusion of hostilities on Bataan. He made this decision entirely on his own responsibility and with the full

[457]

knowledge that he was acting contrary to orders.17

Having made his decision, General King called his staff to his tent at midnight to tell them what he had determined to do and why. At the outset he made it clear that he had not called the meeting to ask for the advice or opinion of his assistants. The "ignominious decision," he explained, was entirely his and he did not wish anyone else to be "saddled with any part of the responsibility." "I have not communicated with General Wainwright," he declared, "because I do not want him to be compelled to assume any part of the responsibility." Further resistance, he felt, would only be an unnecessary and useless waste of life. "Already our hospital, which is filled to capacity and directly in the line of hostile approach, is within range of enemy light artillery. We have no further means of organized resistance."18

Though the decision to surrender could not have surprised the staff, it "hit with an awful bang and a terrible wallop." Everyone had hoped for a happier ending to the grim tragedy of Bataan, and when General King walked out of the meeting "there was not a dry eye present."19

There was much to do in the next few hours to accomplish the orderly surrender of so large and disorganized a force: all units had to be notified of the decision and given precise instructions; selected individuals and units had to be sent to Corregidor; and everything of military value had to be destroyed. The first task was to establish contact with the Japanese and reach agreement on the terms of the surrender. Col. E. C. Williams and Maj. Marshall H. Hurt, Jr., both bachelors, volunteered to go forward under a white flag to request an interview for General King with the Japanese commander. Arrangements for their departure were quickly made. They would time their journey so as to arrive at the front lines at daylight, just as the destruction of equipment was being completed.

In the event the Japanese commander refused to meet General King, Williams was authorized to discuss surrender terms himself. These terms were outlined in a letter of instructions King prepared for Williams. The basic concession Williams was to seek from the Japanese was that Luzon Force headquarters be allowed to control the movement of its troops to prison camp. Williams was also instructed to mention spe-

[458]

cifically the following points if he discussed terms with the Japanese:

a. The large number of sick and wounded in the two General hospitals, particularly Hospital #1 which is dangerously close to the area wherein artillery projectiles may be expected to fall if hostilities continue. b. The fact that our forces are somewhat disorganized and that it will be quite difficult to assemble them. This assembling and organizing of our own forces, necessary prior to their being delivered as prisoners of war, will necessarily take some time and can be accomplished by my own staff and under my direction. c. The physical condition of the command due to long siege, during which they have been on short rations, which will make it very difficult to move them a great distance on foot. d. . . . e. Request consideration for the vast number of civilians present at this time in Bataan, most of whom have simply drifted in and whom we have to feed and care for. These people are in no way connected with the American or Filipino forces and their presence is simply incidental due to circumstances under which the Bataan phase of hostilities was precipitated.20 |

While Williams and Hurt were making preparations to leave, every effort was made to warn all unit commanders of the decision to surrender. There was no difficulty in alerting II Corps since Parker's command post was now adjacent to King's; General Jones was notified by telephone. The two corps commanders in turn informed the units under their control. Bluemel, whose troops had reached the Lamao River, was instructed by Parker to hold his line only until daylight. When he asked what would happen at that time he was told that "a car carrying a white flag would go through the lines on the east road . . . and that there must be no firing after the car passed."21

Bluemel told his regimental commanders and directed them to alert their own officers immediately. Not all units were informed so promptly, and it was only by a narrow margin that these units escaped disaster the next morning.

When Colonel Williams and Major Hurt finally started toward the front lines about 0330 of the 9th, the destruction of equipment was already under way.22 Depot and warehouse commanders had been alerted about noon of the 8th to prepare for demolitions and about midnight the order to begin the destruction was given by Luzon Force headquarters. Some commanders anticipated the order and destruction of equipment began somewhat earlier than midnight. The Chemical Warfare depot began to dump chemicals into the bay during the afternoon and completed the task during the night.23

As though nature had conspired to add to the confusion, an earthquake of serious proportions shook the peninsula "like a leaf" at about 2130.24 About an hour later the Navy started to destroy its installations at Mariveles. "Pursuant to orders from General Wainwright," Captain Hoeffel informed the Navy Department, "am destroying and sinking Dewey Drydock, Canopus, Napa, Bittern tonight."25 Soon the rumble of explosions could be heard from Mariveles

[459]

while flames shot high above the town, lighting up the sky for miles around. The climax came when the Canopus blew up with a tremendous roar: "She seemed," wrote an observer, "to leap out of the water in a sheet of flame and then drop back down heavily like something with all the life gone out of it."26

The Navy's fireworks were but the prelude to the larger demolitions that were to follow when the Army's ammunition was destroyed. Though stored in the congested area adjacent to General Hospital No. 1, the engineer and quartermaster depots, and Luzon Force and II Corps headquarters, the TNT and ammunition had to be destroyed where they were. There was no time to move them to a safer place and hardly time to transfer the hospital patients away from the danger area. In the dumps were hundreds of thousands of rounds of small-arms ammunition and artillery shells of all calibers. Powder trains were laid to the separate piles of ammunition, and shells of larger caliber were set off by rifle fire.

Destruction began shortly after 2100 and at 0200 the first TNT warehouses went up with an explosion that fairly rocked the area. Then followed a most magnificent display of fireworks. Several million dollars worth of explosives and ammunition filled the sky "with bursting shells, colored lights, and sprays of rainbow colors. . . . Never did a 4th of July display equal it in noise, lights, colors or cost."27 After the explosion shell fragments of all sizes fell like hail and men in the vicinity took refuge in their foxholes. The headquarters building at King's command post, a flimsy structure about 200 by 20 feet, was knocked over by the blast and the furniture was scattered in all directions. When morning came the men were surprised to note that all overhead cover was gone. "It is miraculous," wrote one officer, "that we came through this."28

In the confusion and disorganization of the last night of the battle, the evacuation of personnel to Corregidor proved difficult and sometimes impossible. The 45th Infantry (PS), which Wainwright had requested, never reached Mariveles where the barges waited. The regiment was in the I Corps area in the Pantingan valley when it received the orders to move, but it was unable to make the journey in time and was caught on Bataan.29

The nurses were more fortunate. Most of them did escape but only after harrowing experiences. Given thirty minutes to make ready for the journey, the nurses were cautioned to take with them only what they could carry. They boarded trucks in the darkness and made their way south at a snail's pace along the congested East Road. The group from General Hospital No. 2 was held up by the explosions from the ammunition dump which went up just as the convoy reached the road adjacent to the storage area. These nurses almost failed to get through. The barge left without them shortly before daylight and it was only through the "vim, vigor, and swearing" of General Funk that a motor boat was sent from Corregidor to carry them across the North Channel. They left the Mariveles dock after daylight and despite the bombs

[460]

and bullets from a lone Japanese plane reached Corregidor in safety.30

Altogether about 2,000 persons, including 300 survivors of the 31st Infantry (US), Navy personnel, some Scouts from the 26th Cavalry, and Philippine Army troops, escaped from Bataan in small boats and barges that night. The remainder of General King's force of 78,000 was left behind to the tender mercy of the Japanese.31

Meanwhile, Colonel Williams and Major Hurt had gone forward to meet the Japanese commander. They began their journey in a reconnaissance car with motorcycle escort, but, unable to make progress against the heavy traffic moving away from the front lines, were soon forced to abandon the car. Williams climbed on the back of the motorcycle and continued forward, leaving Hurt to make his way as best he could on foot. "After talking to myself," wrote the major in his diary, "saying a few prayers, wondering what is in store for me in the future, bumming rides and a lot of walking" against the tide of "crouching, demoralized, beaten foot soldiers," he met Williams again on the East Road, two miles south of the front lines.32 By this time the Colonel had acquired a jeep and driver and the two men started forward again. Except for the faraway explosions and "the chattering teeth of our driver," all was quiet.

Williams and Hurt reached the front line without further incident. There they found Lt. Col. Joseph Ganahl with some tanks, two 75-mm. guns (SPM), and a few troops. At 0530 Ganahl and his men withdrew, leaving Williams, Hurt, and the driver alone. An hour later, as the sky was turning light, they drove forward into Japanese-held territory. Soon after about thirty "screaming" Japanese with "bayonets flashing" rushed at them.33 Waving a bedsheet, their improvised white flag, both men descended from the jeep with raised hands. For the moment the entire mission was in jeopardy but fortunately a Japanese officer arrived and Williams was able to make him understand by signs and by waving his instructions in the officer's face that he wished to see the commanding officer. The Japanese got into his car, motioning for Williams and Hurt to follow. With a sigh of relief they drove on, past American prisoners with wrists tied behind them and Japanese soldiers making ready for the day's tasks. After a three-mile ride, their jeep was halted and the two Americans were taken to meet General Nagano whose detachment was moving down the East Road. An interpreter read Williams' letter of instructions, and, following a brief discussion, Nagano agreed to meet General King at the Experimental Farm Station near Lamao, close to the front lines.34

Hurt was sent back to get the general and Williams was kept at Japanese headquarters. Escorted to the front lines by Japanese tanks, Major Hurt made his way down the East Road, "past blown-up tanks, burning trucks, broken guns," and reached Luzon Force headquarters at 0900.35 Within a few minutes General King was ready to go forward.

[461]

SURRENDER ON BATAAN

On Corregidor General Wainwright spent the night in ignorance of these events. At 0300 he spoke to King on the telephone but King did not mention his decision to surrender.36 It was only three hours later, at 0600, that General Wainwright learned from his assistant operations officer, Lt. Col. Jesse T. Traywick, Jr., that General King had sent an officer to the Japanese to arrange terms for the cessation of hostilities. Shocked, he shouted to Traywick, "Go back and tell him not to do it."37

But it was too late. Williams and Hurt were already on their way to meet Nagano and General King could not be reached by telephone or radio.38 Regretfully General Wainwright wrote to MacArthur:

[462]

SURRENDER ON BATAAN

At 6 o'clock this morning General King . . . without my knowledge or approval sent a flag of truce to the Japanese commander. The minute I heard of it I disapproved of his action and directed that there would be no surrender. I was informed it was too late to make any change, that the action had already been taken. . . . Physical exhaustion and sickness due to a long period of insufficient food is the real cause of this terrible disaster. When I get word what terms have been arranged I will advise you.39 |

For General King, Wainwright had no criticism. "It has never been and is not my intention to reflect upon General King," he later told MacArthur, "as the decision which he was forced to make required unusual courage and strength of character."40 Soon he would be forced to make the same decision.

It was about 0900 when King, in his last clean uniform, went forward to meet General Nagano. He felt, he said later, like General Lee who on the same day seventy-seven years earlier, just before his meeting with Grant at Appomatox, had remarked: "Then there is nothing left to do but to go

[463]

and see General Grant, and I would rather die a thousand deaths."41 With King when he left his command post were his two aides, Majors Wade Cothran and Tisdelle; his operations officer, Colonel Collier; and Major Hurt, who was to guide them to the meeting place. General Funk remained behind to supervise the completion of the demolitions and the arrangements for the surrender of the Luzon Force.

The group left in two jeeps. In the first were Collier and Hurt; 150 yards to the rear in the second jeep were the general and his aides. Despite the white flags prominently displayed on both vehicles and wildly waved by Collier and Tisdelle, they were immediately bombed and strafed by low-flying Japanese aircraft. Fortunately the road was a winding one and offered ample protection on each side. The planes came in at very low altitude, sprayed the road with their machine guns or dropped a string of small bombs, made a wide circle, then banked and came in again for another try. "One smart boy," wrote Colonel Collier, "dropped out of formation and . . . cut loose with his machine guns just in front of a curve."42 Only the whine of the ricocheting bullets warned the driver of the first jeep in time to avert disaster by jamming on his brakes and piling into the embankment. "The attack passed like a Texas whirlwind" and the men stopped with relief and "took a full breath of good fresh air."43 The attacks were almost continuous and at least once in every 200 yards the entire group was forced to jump hastily from the vehicles and seek cover in a ditch or behind a tree.

After more than an hour of this game of hare and hounds, when the general's uniform was as disheveled as those he had left behind, a Japanese reconnaissance plane appeared over the road and the pilot dipped his wings and waved in recognition. Apparently this was the signal to the attacking planes to keep away and the rest of the journey was uneventful. At the bridge over the Lamao River the group passed Japanese soldiers with fixed bayonets but were allowed to proceed without interference. Waiting for them was the Japanese soldier who had guided Major Hurt to the front lines earlier. He greeted them courteously and escorted them to a house near by in front of which General Nagano was seated with Colonel Williams. It was now 1100; the general and his party had spent two hours traveling a distance of about three miles.44

General Nagano, who spoke no English, opened the meeting by explaining through an interpreter that he was not authorized to make any arrangements himself but that he had notified General Homma an American officer was seeking a meeting to discuss terms for the cessation of hostilities. A representative from 14th Army headquarters, he told King, would arrive very soon. A few minutes later a shiny Cadillac drew up at the building before which the envoys were waiting

[464]

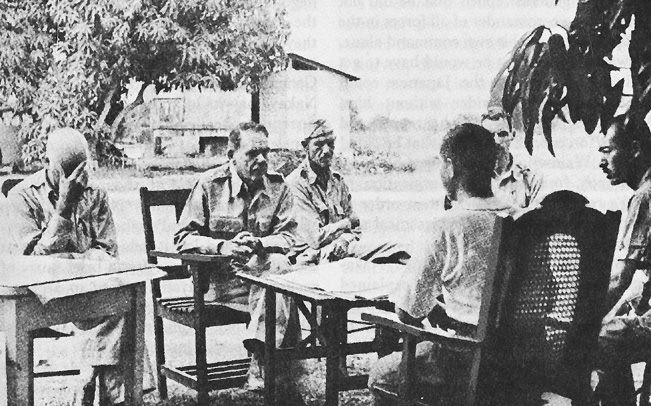

DISCUSSING SURRENDER TERMS with Colonel Nakayama. Facing forward, left to right, Col. Everett C.

Williams, Maj. Gen. Edward P. King, Jr., Maj. Wade Cothran, and Maj. Achille C. Tisdelle.

and Colonel Nakayama, the 14th Army senior operations officer, emerged, accompanied by an interpreter.45 General King rose to greet him, but Nakayama ignored him and took a seat at the head of the table. King resumed his seat at the opposite end, erect with his hands forward in front of him. "I never saw him look more like a soldier," wrote his aide, "than in this hour of defeat."46

Nakayama had come to the meeting without any specific instructions about accepting a surrender or the terms under which a surrender would be acceptable. Apparently there was no thought in Homma's mind of a negotiated settlement. He believed that the American envoy was a representative from General Wainwright and had sent Nakayama to represent him since he was unwilling to meet with any person of lesser rank.47

The discussion got off to a bad start when Colonel Nakayama, fixing his glance on General King, asked: "You are General Wainwright?" When King said he was not and identified himself, Nakayama asked where Wainwright was and why he had not

[465]

come. The general replied that he did not speak for the commander of all forces in the Philippines but for his own command alone. He was then told that he would have to get Wainwright and that the Japanese could not accept any surrender without him. Again King declared that he represented only the forces on Bataan and that he could not get Wainwright. The Japanese were apparently insisting on a clarification of King's relation to Wainwright in order to avoid having to accept the piecemeal surrender of Wainwright's forces.

General King finally persuaded Nakayama to consider his terms. He explained that his forces were no longer fighting units and that he was seeking an arrangement to prevent further bloodshed. He asked for an armistice and requested that air bombardment be stopped at once. Nakayama rejected both the request for an immediate armistice and the cessation of air bombardment, explaining that the pilots had missions until noon and that the bombardment could not be halted until then. King then asked that his troops be permitted to march out of Bataan under their own officers and that the sick, wounded, and exhausted men be allowed to ride in the vehicles he had saved for this purpose. He promised to deliver his men at any time to any place designated by General Homma. Repeatedly he asked for assurance that the American and Filipino troops would be treated as prisoners of war under the provisions of the Geneva Convention.

To all these proposals Nakayama turned a deaf ear. The only basis on which he would consider negotiations for the cessation of hostilities, he asserted, was one which included the surrender of all forces in the Philippines. "It is absolutely impossible for me," he told King flatly, "to consider negotiations ... in any limited area."48 If the forces on Bataan wished to surrender they would have to do so by unit, "voluntarily and unconditionally." Apparently General King understood this to mean that Nakayama would accept his unconditional surrender. Realizing that his position was hopeless and that every minute delayed meant the death of more of his men, General King finally agreed at about 1230 to surrender unconditionally. Nakayama then asked for the general's saber, but King explained he had left it behind in Manila at the outbreak of war. After a brief flurry of excitement, Nakayama agreed to accept a pistol instead and the general laid it on the table. His fellow officers did the same, and the group passed into captivity.

No effort was made by either side to make the surrender a matter of record with a signed statement. General King believed then and later that though he had not secured agreement to any of the terms he had requested he had formally surrendered his entire force to Homma's representative. The Japanese view did not grant even that much. As Nakayama later explained: "The surrender . . . was accomplished by the voluntary and unconditional surrender of each individual or each unit. The negotiations for the cessation of hostilities failed."49 King's surrender, therefore, was interpreted as the surrender of a single individual to the Japanese commander in the area, General Nagano, and not the surrender of an organized military force to the supreme enemy commander. He, Colonel Williams, and the two aides were kept in custody by the Japanese as a guarantee that there would be no further resistance. Though they were not

[466]

so informed, they were, in fact, hostages and not prisoners of war.

Colonel Collier and Major Hurt, accompanied by a Japanese officer, were sent back to headquarters to pass on the news of the surrender to General Funk. On the way, they were to inform all troops along the road and along the adjoining trails to march to the East Road, stack arms, and await further instructions. Orders for the final disposition of the troops would come from Homma. Meanwhile, by agreement with Nagano, the Japanese forces along the east coast would advance only as far as the Cabcaben airfield.50

The battle for Bataan was ended; the fighting was over. The men who had survived the long ordeal could feel justly proud of their accomplishment. For three months they had held off the Japanese, only to be overwhelmed finally by disease and starvation. In a very real sense theirs had been "a true medical defeat," the inevitable outcome of a campaign of attrition, of "consumption without replenishment."51 Each man had done his best and none need feel shame.

The events that followed General King's surrender present a confused and chaotic story of the disintegration and dissolution of a starved, diseased, and beaten army. This story reached its tragic climax with the horrors and atrocities of the 65-mile "death march" from Mariveles to San Fernando.52 Denied food and water, robbed of their personal possessions and equipment, forced to march under the hot sun and halt in areas where even the most primitive sanitary facilities were lacking, clubbed, beaten, and bayoneted by their Japanese conquerors, General King's men made their way into captivity. Gallant foes and brave soldiers, the battling bastards had earned the right to be treated with consideration and decency, but their enemies had reserved for them even greater privations and deeper humiliation than any they had yet suffered on Bataan. How hard their lot was to be none knew but already many faced the future with heavy heart and "feelings of doubt, foreboding, and dark uncertainty."53

[467]

Return to Table of Contents

Return to Chapter XXV |

Go to Chapter XXVII |

Last updated 1 June 2006 |