CHAPTER XIII

Into Bataan

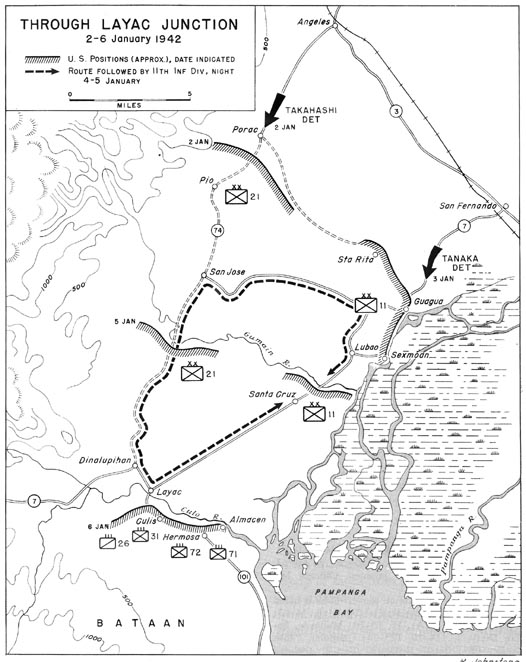

By the first week of January 1942 the American and Filipino troops withdrawing from both ends of Luzon had joined at San Fernando and begun the last lap of their journey to Bataan. In ten days they had retired from Lingayen Gulf and Lamon Bay to Guagua and Porac, on the two roads leading into Bataan. There they had halted and established a line only fifteen miles from the base of the peninsula. The longer they could hold, the more time would be available to prepare the final defenses in Bataan.

Along the ten-mile line from Guagua to Porac, paralleling the road between the two barrios, General Wainwright had placed the 11th and 21st Divisions (PA), as well as armor and cavalry. (Map 9) On the left (west), around Porac, was the 21st Division with the 26th Cavalry (PS) to its rear, in force reserve. On the east was the 11th Division, its right flank covered by almost impenetrable swamps crisscrossed by numerous streams. In support of both divisions was General Weaver's tank group.

The troops along this line, the best in the North Luzon Force, though battle tested and protected by mountains on the west and swamps on the east, felt exposed and insecure. They were convinced that they were opposing the entire Japanese 14th Army, estimated, according to Colonel Mallonée, to number 120,000 men.1 Actually, Japanese strength on Luzon was about half that size, and only two reinforced regiments with tanks and artillery faced the men on the Guagua-Porac line.

From Cabanatuan, where Homma had moved his headquarters on New Year's Day, 14th Army issued orders to attack the line before Bataan.2 A force, known as the Takahashi Detachment after its commander, Lt. Col. Katsumi Takahashi, and consisting of the 9th Infantry (less two companies), two batteries of the 22d Field Artillery, and the 8th Field Heavy Artillery Regiment (less one battalion), was to strike out from Angeles along Route 74, smash the American line at Porac, and go on to seize Dinalupihan, an important road junction at the entrance to Bataan. To support Takahashi's drive down Route 74, Homma ordered the 9th Independent Field Heavy Artillery Battalion, then approaching Tarlac, to push on to Porac.

A second force, drawn largely from the 48th Division, was organized for the drive down Route 7 through Guagua to Hermosa, a short distance southeast of Dinalupihan. This force, organized at San Fernando and led by Colonel Tanaka, was composed of the 2d Formosa and a battalion of the 47th Infantry supported by a company of tanks and three battalions of

[216]

MAP 9

[217]

artillery. Both detachments were to receive support from the 5th Air Group, which was also to strike at targets on Bataan. The attack would begin at 0200 on 2 January.3

The Japanese expected to smash the defenses before Bataan easily and to make quick work of the "defeated enemy," who, in General Morioka's striking phrase, was like "a cat entering a sack."4 General Homma fully intended to draw the strings tight once the Americans were in the sack, thereby bringing the campaign to an early and successful conclusion. He was due for a painful disappointment.

The Left Flank

In the 21st Division sector, just below Porac, two regiments stood on the line. On the west (left), from the mountains to Route 74, was the 21st Infantry, spread thin along the entire front. On the right, behind the Porac-Guagua road, was the 22d Infantry. The 23d Infantry, organized at the start of hostilities, was in reserve about five miles to the rear. The division's artillery regiment was deployed with its 3d Battalion on the left, behind the 21st Infantry, and the 1st Battalion on the right. The 2d Battalion was in general support, but placed immediately behind the 3d Battalion which was short one battery.5

Seven miles south of Porac, at San Jose, was the force reserve, the 26th Cavalry, now partly rested and reorganized after its fight in the Lingayen area. Its mission was to cover the left flank of the 21st Division and extend it westward to the Zambales Mountains. Colonel Pierce, the cavalry commander, dispatched Troop G, equipped with pack radio, forward toward Porac, to the left of the 21st Infantry. The rest of the regiment he kept in readiness at San Jose. The 26th Cavalry was not the only unit in San Jose; also there were the 192d Tank Battalion and the headquarters of the 21st Division. The place was so crowded that Colonel Mallonée, who wanted to establish the command post of the 21st Field Artillery there, was forced to choose another location because "the town was as full as the county seat during fair week."6

The expected attack against the Guagua-Porac line came on the afternoon of 2 January, when an advance detachment from the 9th Infantry coming down Route 74 hit the 21st Infantry near Porac. Although the enemy detachment was small, it was able to force back the weakened and thinly spread defenders about 2,000 yards to the southwest, to the vicinity of Pio. Stiffened by the reserve, the regiment finally halted the Japanese advance just short of the regimental reserve line. Efforts to restore the original line failed, leaving the artillery exposed to the enemy infantry, who were "about as far from the muzzles as outfielders would play for Babe Ruth if there were no fences."7

Division headquarters in San Jose immediately made plans for a counterattack using a battalion of the reserve regiment, the

[218]

23d Infantry. But darkness fell before the attack could be mounted and the 2d Battalion, 23d Infantry, the unit selected for the counterattack, was ordered to move up at dawn and restore the line on the left. When the 2d Battalion moved into the line, the 21st Infantry would regroup to the right, thus shortening its front.

That night the stillness was broken only by fire from the Philippine artillery which had pulled back about 600 yards. When morning came the enemy was gone. Reports from 21st Infantry patrols, which had moved forward unmolested at the first sign of light, encouraged division headquarters to believe that the original main line of resistance could be restored without a fight and orders were issued for a general advance when the 2d Battalion, 23d Infantry, tied in with the 21st Infantry.

American plans for a counterattack were premature. The evening before, the main force of the Takahashi Detachment had left its assembly area midway between Bamban and Angeles and marched rapidly toward Porac. The 8th Field Heavy Artillery Regiment (less one battalion), with its 105-mm. guns, had accompanied the force and by morning was in position to support the infantry attack. Thus, when the 2d Battalion, 23d Infantry, began to advance it was met first by punishing small-arms fire from the infantry, then by fire from the 105-mm. guns of the 8th Field Artillery. At the same time three Japanese aircraft swung low to strafe the road in support of the enemy attack. The momentum of the advance carried the Japanese below Pio, where they were finally stopped.

When news of the attack reached General Wainwright's headquarters, the most alarming item in the report was the presence of Japanese medium artillery, thought to be heavy guns, on the left of the American line. This artillery represented a serious threat, and the 21st Division was ordered to "hold the line or die where you are."8 General Capinpin did his best, but he had only two battalions of the 23d Infantry, an unseasoned and untrained unit, left in reserve. One of these battalions was in North Luzon Force reserve and it was now ordered to move to the 11th Division sector near Guagua where a heavy fight was in progress.

Meanwhile, Colonel Takahashi had launched an assault against the 21st Infantry. First the battalion on the left gave way and within an hour the reserve line also began to crumble. By noon the left flank of the 21st Infantry was completely disorganized. The right battalion, though still intact, fell back also lest it be outflanked. This withdrawal exposed the left flank of the 22d Infantry on its right.

Colonel Takahashi lost no time in taking advantage of the gap in the American line. Elements of the 9th Infantry drove in between the two regiments, hitting most heavily the 1st Battalion, 22d Infantry, on the regimental left. The action which followed was marked by confusion. The noise of artillery fire and the black smoke rising from the burning cane fields reduced the troops to bewildered and frightened men. At one time the 21st Infantry staff was nearly captured when the onrushing enemy broke through to the command post. A group of tanks from the 11th Division sector, ordered to attack the Japanese line in front of the 21st Division, showed a marked disinclination to move into the adjoining sector without orders from the tank group commander. Before the ferocity of the Jap-

[219]

anese attack the defending infantry line melted away.9

Had it not been for the artillery the Japanese attack might well have resulted in a complete rout. Fortunately, the 21st Field Artillery acted in time to halt Takahashi's advance. The 1st Battalion on the right, behind the 22d Infantry, covered the gap between the two regiments and fired directly against the oncoming Japanese at a range of 600-800 yards. The 2d and 3d Battalions delivered direct fire up the draw leading through Pio. Notwithstanding the punishing artillery fire, the 9th Infantry continued to attack. For six hours, until darkness closed in, the left portion of the 21st Division line was held by the guns of the 21st Field Artillery alone, firing at close range across open fields. "As attack after attack came on, broke, and went back," wrote Colonel Mallonée, "I knew what Cushing's artillerymen must have felt with the muzzles of their guns in the front line as the Confederate wave came on and broke on the high water mark at Gettysburg."10

Quiet settled down on the 21st Division front that night. The Takahashi Detachment, its attack halted by the effective fire of the artillery, paused to reorganize and take stock of the damage. The next day, 4 January, there was no action at all on the left and only intermittent pressure on the right. The Japanese did manage to emplace one or two of their 105-mm. guns along the high ground to the west and during the day fired on the rear areas. Fortunately, their marksmanship was poor and although they made life behind the front lines uncomfortable they inflicted no real damage.

On the afternoon of the 4th, as a result of pressure on the 11th Division to the east, General Wainwright ordered the 21st Division to withdraw under cover of darkness to the line of the Gumain River, about eight miles south of Porac. That night the division began to move back after successfully breaking contact with the enemy. Despite the absence of enemy pressure there was considerable confusion during the withdrawal. By daylight of the 5th, however, the troops were across the Gumain where they began to prepare for their next stand. Division headquarters, the 23d Infantry, the division signal company, and other special units were at Dinalupihan, with the 21st Field Artillery located just east of the town.

The Right Flank

Along the east half of the Guagua-Porac line stood the 11th Division (PA). The 11th Infantry was on the left, holding the Guagua-Porac road as far north as Santa Rita. The regiment, in contact with the 21st Division on the left only through occasional patrols, had three battalions on the line. The 2d Battalion was on the left, the 1st in the center, and the 3d on the right. Next to the 11th was the 13th Infantry, which held Guagua and was in position across Route 7. Extending the line southeast from Guagua to Sexmoan were two companies of the 12th Infantry. The 11th Field Artillery, for the first time since the start of the war, was in support of the di-

[220]

vision. Part of the 194th Tank Battalion and Company A of the 192d provided additional support.11

The Japanese attack on the right flank of the Guagua-Porac line came on 3 January. Leaving San Fernando at 0400 the reinforced Tanaka Detachment had advanced cautiously along Route 7. At about 0930 the point of the Japanese column made contact with a platoon of tanks from Company C, 194th, posted about 1,000 yards north of Guagua. Under tank fire and confined to the road because of the marshy terrain on both sides, the Japanese halted to await the arrival of the main force. About noon, when the force in front became too formidable, the American tanks fell back to Guagua. The Japanese continued to advance slowly. Forced by the nature of the terrain into a frontal assault along the main road and slowed down by the numerous villages along the line of advance, the attack, the Japanese admitted, "did not progress as planned."12 Artillery was brought into support and, late in the afternoon, the 75-mm. guns opened fire, scoring at least one hit on the 11th Infantry command post. The defending infantry were greatly cheered by the sound of their own artillery answering the Japanese guns. Organized after the start of the war and inadequately trained, the men of the 11th Field Artillery, firing from positions at Guagua and Santa Rita, made up in enthusiasm what they lacked in skill.13

The Japanese artillery fire continued during the night and increased in intensity the next morning, 4 January, when a battalion of 150-mm. howitzers joined in the fight. In the early afternoon an enemy column spearheaded by tanks of the 7th Tank Regiment broke through the 13th Infantry line along Route 7 and seized the northern portion of Guagua. Another column hit the 3d Battalion, 11th Infantry, to the left of the 13th, inflicting about 150 casualties. The two units held on long enough, however, for the 1st and 2d Battalions of the 11th Infantry to pull out. They then broke contact and followed the two battalions in good order.14

During this action Company A, 192d Tank Battalion, and elements of the 11th Division attempted to counterattack by striking the flank of the Japanese line before Guagua. This move almost ended in disaster. The infantry on the line mistook the tanks for enemy armor and began dropping mortar shells on Company A, and General Weaver, who was in a jeep attempting to co-ordinate the tank-infantry attack, was almost hit. The mistake was discovered in time and no serious damage was done.

[221]

When news of the Japanese breakthrough at Guagua reached General Wainwright on the afternoon of the 4th he decided it was time to fall back again. The next line was to be south of the Gumain River, and orders were issued to the 11th, as well as the 21st Division, to withdraw to the new line that night.

General Brougher's plan of withdrawal called for a retirement along Route 7 through Guagua and Lubao to the new line. The rapid advance of the Tanaka Detachment through Guagua and down Route 7 toward Lubao late that afternoon, however, cut off this route of retreat of the 11th Infantry and other elements on the line. A hasty reconnaissance of the area near the highway failed to disclose any secondary roads or trails suitable for an orderly retirement. To withdraw cross-country was to invite wholesale confusion and a possible rout. The only course remaining to the cutoff units was to traverse a thirty-mile-long, circuitous route through San Jose, in the 21st Division sector, then down Route 74 to Dinalupihan. There the men would turn southeast as far as Layac Junction and then north along Route 7 to a point where they could form a line before the advancing Tanaka Detachment.

That evening, 4 January, the long march began. Those elements of the 11th Division cut off by the Japanese advance, and Company A, 192d Tank Battalion, reached San Jose without interference from the enemy but not without adding to the confusion already existing in the 21st Division area.

Meanwhile at San Jose, General Brougher, the 11th Division commander, had collected all the trucks and buses he could find and sent them forward to carry his men. With this motor transportation, the 11th Infantry was able to take up a position along Route 7, between Santa Cruz and Lubao, by about 0600 of 5 January. This line was about one mile southwest of the Gumain River, the position which the division had originally been ordered to occupy. Troops arriving on this line found themselves under small-arms fire from the Tanaka Detachment, which had entered Lubao the previous evening.

A short distance north of this line, an outpost line had already been established the previous afternoon by General Brougher with those troops who had been able to withdraw down Route 7. The infantry troops on this line were from the 12th Infantry, part of which had pulled back along Route 7. Brougher had rounded up about two hundred men from the regiment, together with the ten guns of the 11th Field Artillery and some 75-mm. SPM's, and formed a line on Route 7 between Lubao and Santa Cruz. For fourteen hours, from the afternoon of 4 January to the morning of 5 January, these troops under the command of Capt. John Primrose formed the only line between the enemy and Layac Junction, the entrance into Bataan. Early on 5 January when the new line was formed by the troops who had withdrawn through San Jose, Primrose and his men pulled back to join the main force of the division.

The withdrawal of the 194th Tank Battalion from Guagua had been accomplished only after a fierce fight. Colonel Miller, the tank commander, had ordered the tanks to pull out on the morning of the 4th. Under constant enemy pressure, the tanks began a slow withdrawal, peeling off one at a time. Guarding their flank was a force consisting of a few tanks of Company C, 194th, and some SPM's from Capt. Gordon H. Peck's provisional battalion posted

[222]

at a block along the Sexmoan-Lubao road. At about 1600 Peck and Miller had observed a large enemy force approaching. This force, estimated as between 500 and 800 men, supported by machine guns, mortars, and artillery, was led by three Filipinos carrying white flags, presumably under duress. The tanks and SPM's opened fire, cutting the Japanese column to pieces. The 194th Tank Battalion then left burning Guagua and Lubao and moved south to positions a mile or two above Santa Cruz. The tanks and SPM's at the block covered its withdrawal.

Some time after midnight, between 0200 and 0300 on 5 January, the covering force was hit again, this time by infantry and artillery of the Tanaka Detachment. Attacking in bright moonlight across an open field and along the road, the enemy came under direct fire from the American guns. Driven back with heavy casualties, he attacked again and again, and only broke off the action about 0500, at the approach of daylight. Later in the day the Tanaka Detachment, seriously depleted by casualties, was relieved by Col. Hifumi Imai's 1st Formosa Infantry (less one battalion) to which were attached Tanaka's tanks and artillery.

By dawn of 5 January, after two days of heavy and confused fighting, the Guagua-Porac line had been abandoned and the American and Filipino troops had pulled back to a new line south and west of the Gumain River. The 21st Division on the west had retired to a position about eight miles below Porac and was digging in along the bank of the river; to the east the 11th Division had fallen back six miles and stood along a line about a mile south of the river. But the brief stand on the Guagua-Porac line had earned large dividends. The Japanese had paid dearly for the ground gained and had been prevented from reaching their objective, the gateway to Bataan. More important was the time gained by the troops already in Bataan to prepare their positions.

The only troops remaining between the enemy and Bataan-the 11th and 21st Divisions, the 26th Cavalry, and the tank group-were now formed on their final line in front of the peninsula. This line, approximately eight miles in front of the access road to Bataan and generally along the Gumain River, blocked the approach to Bataan through Dinalupihan and Layac Junction.

Both Dinalupihan and Layac Junction lie along Route 7. This road, the 11th Division's route of withdrawal, extends southwest from San Fernando to Layac where it joins Route 110, the only road leading into Bataan. At Layac, Route 7 turns sharply northwest for 2,000 yards to Dinalupihan, the southern terminus of Route 74 along which the 21st Division was withdrawing. Route 7 then continues west across the base of the peninsula to Olangapo on Subic Bay, then north along the Zambales coast to Lingayen Gulf, a route of advance the Japanese had fortunately neglected in favor of the central plain which led most directly to their objective, Manila.

Layac Junction, where all the roads to Bataan joined, was the key point along the route of withdrawal. Through it and over the single steel bridge across the Culo River just south of the town would have to pass the troops converging along Routes 7 and 74. The successful completion of this move

[223]

would require the most precise timing, and, if the enemy attacked, a high order of road discipline.

Through the Layac Bottleneck

The withdrawal from the Gumain River through Layac Junction, although made without interference from the enemy, was attended by the greatest confusion. On the east, where the 11th Division was in position astride Route 7, there were a few skirmishes between patrols on 5 January but no serious action. General Brougher had received a battalion of the 71st Infantry to strengthen his line but the battalion returned to its parent unit at the end of the day without ever having been engaged with the enemy.15

In the 21st Division area to the west there was much milling about and confusion on the 5th. Work on the Gumain River position progressed very slowly during the morning, and the troops showed little inclination to extend the line eastward to make contact with the 11th Division. During the day contradictory or misunderstood orders sent the men forward and then pulled them back, sometimes simultaneously. Shortly before noon General Capinpin, needlessly alarmed about the situation on the 11th Division front and fearful for the safety of his right (east) flank, ordered a withdrawal to a point about a mile above Dinalupihan. The movement was begun but halted early in the afternoon by an order from General Wainwright to hold the Gumain River line until further orders.

By midafternoon the division had once more formed a line south of the river. Thinly manned in one place, congested in another, the position was poorly organized and incapable of withstanding a determined assault. In one section, infantry, artillery, and tanks were mixed together in complete disorder. "Everyone," said Colonel Mallonée, "was in everyone else's lap and the whole thing resembled nothing quite as much as the first stages of an old fashioned southern political mass meeting and free barbecue."16

Fortunately for General Capinpin, the Takahashi Detachment on Route 74 did not advance below Pio. This failure to advance was due to an excess of caution on the part of the colonel who, on the 4th, had been placed under the 65th Brigade for operations on Bataan.17 It is, entirely possible that Japanese caution and lack of vigor in pressing home the attack may have been due to a mistaken notion of the strength of the defending forces and a healthy respect for American-led Filipino troops. Had Takahashi chosen this moment to launch a determined attack against the 21st Division he would almost certainly have succeeded in trapping the forces before Bataan.

The troops had hardly taken up their positions behind the Gumain River when General Wainwright issued orders for the withdrawal into Bataan through Layac Junction, to begin at dark. First to cross the bridge over the Culo River below Layac would be the 11th Division, followed closely by the 21st. To cover the withdrawal of the 11th, one battalion of the 21st Division was to sideslip over in front of the 11th Division, while the 26th Cavalry would protect the left flank of the 21st during its withdrawal.18

[224]

The execution of such a maneuver seemed impossible under the conditions existing along the front. The 23d Infantry, in division reserve, was already at Dinalupihan and Colonel O'Day, senior American instructor in the 21st Division, proposed instead to place a battalion of this regiment astride Route 7 behind the 11th Division. General Brougher's troops could then fall back through the covering battalion. This proposal was accepted, and after considerable difficulty "the equivalent of a battalion" was placed in position by dark.19

When night fell the 11th Division withdrew from its positions and moved southwest along Route 7 toward Layac Junction and the road to Bataan. Soon the town was crowded with men and vehicles and as the withdrawal continued became a scene of "terrible congestion," of marching men, trucks, buses, artillery, tanks, horses, and large numbers of staff and command cars. "It looked," remarked one observer, "like the parking lot of the Yale bowl."20

At about 2030 Col. John Moran, chief of staff of the 11th Division, reported that his division had cleared Layac and was across the Culo bridge. The 21st Division was now ordered across. Observing the passage of men, Colonel O'Day wrote: "It was a painful and tragic sight-our soldiers trudging along, carrying inordinate loads of equipment and personal effects. Many had their loads slung on bamboo poles, a pole between two men. They had been marching almost since dark the night before, and much of the daylight hours had been spent in backing and filling. . . ."21

By about midnight of the 5th, the last guns of the 21st Field Artillery had cleared the bridge, and within the next hour all of the foot troops, closely shepherded by the Scouts of the 26th Cavalry, were across. Last to cross were the tanks, which cleared the bridge shortly before 0200 of the 6th. General Wainwright then ordered Capt. A. P. Chanco, commanding the 91st Engineer Battalion, to blow the bridge. The charges were immediately detonated and the span demolished. All of the troops were now on Bataan, and the last gate slammed shut. The Japanese had lost their opportunity again to cut off the retreat. Colonel Imai was still at Santa Cruz and Takahashi still hung back at Porac.22

Holding Action Below Layac Junction

Already formed below Layac Junction when the Culo bridge was blown was another line designed to delay the enemy and gain more time for the Bataan Defense Force. The idea for a delaying action at Layac Junction was contained in WPO-3, the plan that went into effect on 23 December, and General Parker, commander of the Bataan Defense Force, had sent the 31st Infantry (US) there on the 28th to cover the junction.

The importance of this position was stressed by Col. Hugh J. Casey, MacArthur's engineer officer, who, on 2 January, pointed out to General Sutherland that the defense lines then being established on Bataan left to the enemy control of Route 110 which led south from Layac into the peninsula. This road, he felt, should be de-

[225]

nied the Japanese as long as possible. He recommended to General Sutherland, therefore, that a strong delaying action, or, failing that, "definite reference to preparing strong delaying positions . . . should be made."23

These recommendations were apparently accepted, for the same day General MacArthur ordered Wainwright to organize a delaying position south of Layac Junction along Route 110. On completion of this position, control would pass to General Parker, who was to hold until forced to withdraw by a co-ordinated enemy attack.24

Responsibility for the establishment of the Layac Junction line was given to General Selleck who had just reached Bataan with his disorganized 71st Division (PA). The troops assigned were the 71st and 72d Infantry from Selleck's 71st Division, totaling approximately 2,500 men; the 26th Cavalry, now numbering 657 men; and the 31st Infantry (US) of the Philippine Division, the only infantry regiment in the Philippines composed entirely of Americans. Of this force, the 31st was the only unit which had not yet been in action. Artillery support consisted of the 71st Field Artillery with two 75-mm. gun batteries and four 2.95-inch guns; the 1st Battalion of the 23d Field Artillery (PS) with about ten 75's; and the 1st Battalion, 88th Field Artillery (PS) with two batteries of 75's. The tank group and two SPM battalions were also in support.

On 3 and 4 January the 71st Division elements and the 31st Infantry moved into position and began stringing wire and digging in. General Selleck had been denied the use of the 71st Engineers by North Luzon Force, with the result that the construction of defenses progressed slowly. When Colonel Skerry inspected the line on the 4th and 5th he found that the tired and disorganized 71st and 72d Infantry had made little progress in the organization of the ground and that their morale was low. In the 31st Infantry (US) sector, however, he found morale high and the organization of the ground much more effective.

At that time Selleck's forces were spread thin along a line south of Layac Junction across Route 110, which ran southeast and east between Layac and Hermosa. On the right was the 71st Infantry, holding a front along the south bank of Culis Creek-not to be confused with the Culo River immediately to the north. This line, parallel to and just north of Route 110, extended from Almacen, northeast of Hermosa, to a point northeast of Culis, where Culis Creek turned south to cross Route 110. The east-

[226]

ern extremity of the 71st Infantry sector was protected by swamps and a wide river; on the west was the 72d Infantry, straddling Route 110. Its sector was about 1,000 yards below Layac Junction and faced north and east.

Next to the 72d Infantry was the 31st Infantry, with the 1st and 2d Battalions extending the line to the southwest, about 3,000 yards from the nearest hill mass. This exposed left flank was to be covered by the 26th Cavalry, then pulling back through Layac Junction with the 11th and 21st Divisions. In reserve was the 3d Battalion, 31st Infantry, about 1,000 yards to the rear. Supporting the 31st was the 1st Battalion, 88th Field Artillery, on the west, and the 1st Battalion, 23d Field Artillery, to its right, west of Route 110. The 71st Division infantry regiments each had a battalion of the 71st Field Artillery in support.

At approximately 0330 of the 6th of January the 26th Cavalry reached the new line south of Layac Junction and fell in on the left of the 31st Infantry, to the foothills of the Zambales Mountains. It was followed across the bridge by the tanks, which took up supporting positions southwest of Hermosa-the 194th Battalion on the left (west) and the 192d on the right. The 75-mm. SPM's, which withdrew with the tanks, were placed along the line to cover possible routes of advance of hostile tanks.

The line when formed seemed a strong one. In Colonel Collier's opinion, it had "a fair sized force to hold it," and General Parker declared, referring probably to the 31st Infantry sector, that it "lent itself to a good defense . . . was on high ground and had good fields of fire."25

General Selleck did not share this optimism about the strength of his position. To him the front occupied by his troops seemed excessive, with the result that "all units except the 26th Cavalry were over-extended."26 Colonel Skerry's inspection on the 5th had led him to the conclusion that the length of the line held by the disorganized 71st and 72d Infantry was too extended for these units. Selleck thought that his line had another, even more serious weakness, in that part of the right portion faced northeast and the left portion northwest, thus exposing the first to enfilade from the north and the second to enfilade from the east.

Admittedly the position chosen had weaknesses, but no more than a delaying action was ever contemplated along this line. As in the withdrawal of the North Luzon Force from Lingayen Gulf, all that was expected was that the enemy, faced by an organized line, would halt, wait for artillery and other supporting weapons, and plan an organized, co-ordinated attack. By that time the objective- delay-would have been gained, and the line could pull back.

At 0600, 6 January, when all the troops were on the line, Wainwright released General Selleck from his command to Parker's control. After notifying MacArthur of his action he withdrew to Bataan, stopping briefly at Culis where Selleck had his command post. North Luzon Force had completed its mission. Like the South Luzon Force it was now in position behind the first line on Bataan. Only the covering force at Layac Junction denied the enemy free access to Bataan.

Action along the Layac line began on the morning of 6 January with an artillery

[227]

barrage. At about 1000 forward observers reported that Japanese infantry and artillery were advancing down Route 7 toward Layac Junction. This column was part of the Iman Detachment which consisted of the 1st Formosa Infantry, one company of the 7th Tank Regiment, two battalions of the 48th Mountain Artillery armed with 75-mm. guns, and one battalion of the 1st Field Heavy Artillery Regiment with eight 150-mm. howitzers. By 1030 the Japanese column was within artillery range of the defenders and the 1st Battalions of the 23d and 88th Field Artillery Regiments opened fire. The first salvo by the Philippine Scout gunners was directly on the target. Switching immediately to rapid volley fire, the two battalions, joined by the 71st Field Artillery, searched the road from front to rear, forcing the enemy to deploy about 4,200 yards northeast of Layac.27

The Japanese now moved their own artillery into position. The 75's of the 48th Mountain Artillery and the 150-mm. howitzers of the 1st Field Artillery, directed by unmolested observation planes, began to drop concentrated and effective fire on the Americans and Filipinos. It was during this bombardment that Jose Calugas, the mess sergeant of Battery B, 88th Field Artillery, won the Medal of Honor.

General Selleck, without antiaircraft protection, was unable to prevent aerial reconnaissance, with the result that the Japanese 150's, out of range of the American guns, were able to place accurate and punishing fire upon the infantry positions and upon the artillery. Around noon, therefore, Selleck ordered his artillery to new positions, but the observation planes, flying as low as 2,000 feet, reported the changed positions, and the Japanese artillery shifted fire. It enfiladed the 31st Infantry and inflicted great damage on the 71st Infantry and the 1st Battalion, 23d Field Artillery, destroying all but one of the latter's guns. The 88th Field Artillery, in a more protected position, did not suffer as great a loss. That day General MacArthur informed the War Department that the enemy was using his "complete command of the air ... to full effect against our artillery."28

The intense Japanese artillery barrage was the prelude to an advance by the infantry. MacArthur had warned that the Japanese were "apparently setting up a prepared attack in great strength," and, except for his estimate of the strength of the enemy, his analysis was correct.29 At about 1400 a Japanese force of several battalions of infantry crossed the Culo River below Layac Junction and pushed forward the American line. Another force turned north at Layac and moved toward Dinalupihan, entering that undefended town at 1500. An hour later the Japanese who had continued south on reaching Layac hit Selleck's line between the 31st Infantry and the 72d Infantry. Company B, on the right of the 31st line, had been badly shaken by the artillery barrage and fell back in disorder to higher ground about 800 yards to the rear, leaving a gap between Company C on its left and the 72d Infantry on the right. Japanese troops promptly infiltrated. Attempts by the rest of the 1st Battalion, 31st Infantry, to fill the gap failed and Col. Charles L. Steel, the regimental commander, secured his 3d Battalion from Selleck's reserve and ordered it into the line.

[228]

The Japanese, supported by artillery fire, continued to push into the gap, hitting the right of Company C, 31st Infantry, and Company A of the 72d on the left. Lt. Col. Jasper E. Brady, Jr., the 3d Battalion commander, ordered Companies I and L, 31st Infantry, into the sector previously held by Company B. As Company I moved forward, it was caught in the enemy's artillery fire, badly disorganized, and forced back to the rear. Company L, however, continued to press forward. Within thirty minutes from the time it had jumped off to the attack, it had succeeded in restoring the line.30

Outwardly the situation seemed well in hand. But General Selleck was in serious trouble. His overextended line had been partially penetrated, his reserves had been committed, and his artillery was practically out of action. The Japanese were continuing to press south across the Culo River. Should they attack successfully through the 72d Infantry line, they would gain control of the road and cut off Selleck's route of escape. Colonel Steel recommended withdrawal and General Selleck informed Parker that he would not be able to hold out without artillery and infantry reinforcements and that a daylight withdrawal might prove disastrous. At 2200 of the 6th, General Parker ordered a withdrawal under cover of darkness.

Although both the American and Japanese commanders had tanks at their disposal neither had employed them that day. Possibly the Japanese had failed to use armor because there were no bridges over the Culo River. Some of the American tanks had been hit by the Japanese artillery, but not seriously enough to prevent their use. They had not been used to support the attack by the 3d Battalion, 31st Infantry, General Selleck noted caustically, because "the terrain was not considered suitable by the lank commander."31 At about 1830, when it appeared that the Japanese might cut off the route of escape, Colonel Miller, senior tank commander in the area, had moved the tanks toward the highway. They arrived there about 2100, and were met by General Weaver's executive with orders for a further withdrawal southward into Bataan.32

The tanks were already well on their way when the units on the line received orders to pull back. The 71st Division elements experienced no difficulty in withdrawing down the road. The 31st Infantry, leaving three companies on the line as a covering shell, pulled out about 0130 on the morning of the 7th. An hour later, as the shell began to move out, the Japanese launched an attack against Hermosa, cutting off Company E and almost destroying it. The Japanese reached their objective by 0500, but the survivors of Company E

[229]

did not rejoin the regiment until a few days later.33

The 26th Cavalry, which had not been under attack that day, had lost contact with the 31st Infantry on its right. Radio communication proved inadequate; messages were garbled and, in some cases, indecipherable. The code had been changed during the night and no one had informed the 26th Cavalry. Consequently the Scout regiment was not aware of the order to withdraw during the night. It was not until the approach of daylight that the 26th learned of the withdrawal. It began to pull back at 0700 of the 7th. By this time the Japanese controlled the road as far south as Hermosa and the Scouts were compelled to move overland across the mountainous jungle to reach the American line. With the departure of the 26th Cavalry the Layac line disappeared.

At Layac Junction the American and Philippine troops had paid dearly to secure one day of grace for the forces preparing to defend Bataan. Against the longer range Japanese guns the Americans had been defenseless. The line had been penetrated at the first blow, only to be restored and then abandoned. The Japanese had once more failed in their attempt to follow up their advantage.

The withdrawal into Bataan was now complete. Under desperate circumstances and under constant pressure from the enemy, General MacArthur had brought his forces from the north and south to San Fernando and Calumpit. There, in a most difficult maneuver, he had joined the two forces and brought them safely into Bataan, fighting a delaying action all the way. All this had been accomplished in two weeks, during which time positions had been prepared on Bataan and supplies shipped there from Manila and elsewhere. Not a single major unit had been cut off or lost during the withdrawal, and only once, at Cabanatuan, had the American line failed to hold long enough to permit an orderly withdrawal. The success of this complicated and difficult movement, made with ill-equipped and inadequately trained Filipino troops, is a tribute to the generalship of MacArthur, Wainwright, and Jones and to American leadership on the field of battle.

The withdrawal had been a costly one on both sides. General Wainwright's North Luzon Force of 28,000 men had been reduced to about 16,000 largely by the desertion of Filipino soldiers who returned to their homes. Only a small portion of the 12,000 men lost were battle casualties or captured by the enemy. General Jones's South Luzon Force fared much better. Of the 15,000 men in his force originally, General Jones had 14,000 left when he reached Bataan.34 The Japanese suffered close to 2,000 casualties during the period since the first landing. This number included 627 killed, 1,282 wounded, and 7 missing.35

The men who reached Bataan were tired

[230]

and hungry. Before the fight began again they were accorded a brief rest while the enemy reorganized. To Colonel Collier this interlude seemed but an intermission between the acts of a great tragedy entitled "Defense of the Philippines." But before the curtain could go up on the second act, certain off-stage arrangements had to be completed. While these did not directly affect the action on-stage, they exerted a powerful influence on the outcome of the drama.

Return to Table of Contents

Return to Chapter XII |

Go to Chapter XIV |

Last updated 1 June 2006 |