- General Lee, after consulting with

General Eisenhower and with army commanders, proposed adding to this number

physically qualified men from the Communications Zone's Negro units.4

General Eisenhower, General Bradley, and the army commanders agreed. General

Lee then consulted with Brig. Gen. Henry J. Matchett, commanding the Ground

Force Reinforcement Command, and Brig. Gen. Benjamin O. Davis, then Special

Advisor and Coordinator to the Theater Commander on Negro Troops. General

Davis responded enthusiastically and, on Christmas Day, 1944, General Davis,

General Matchett, and the GFRC G-1 drew up a plan to train Negro volunteers

- [688]

- as individual infantry replacements.5

General Lee had already prepared a call to troops, which went out to his

base and section commanders on 26 December with instructions that it be

reproduced and disseminated to troops within twenty-four hours. It read:

-

- 1. The Supreme Commander desires

to destroy the enemy forces and end hostilities in this theater without

delay. Every available weapon at our disposal must be brought to bear upon

the enemy. To this end the Commanding General, Com Z, is happy to offer

to a limited number of colored troops who have had infantry training, the

privilege of joining our veteran units at the front to deliver the knockout

blow. The men selected are to be in the grades of Private First Class and

Private. Non-commissioned officers may accept reduction in order to take

advantage of this opportunity. The men selected are to be given a refresher

course with emphasis on weapon training.

- 2. The Commanding General makes

a special appeal to you. It is planned to assign you without regard to color

or race to the units where assistance is most needed, and give you the opportunity

of fighting shoulder to shoulder to bring about victory. Your comrades at

the front are anxious to share the glory of victory with you. Your relatives

and friends everywhere have been urging that you be granted this privilege.

The Supreme Commander, your Commanding General, and other veteran officers

who have served with you are confident that many of you will take advantage

of this opportunity and carry on in keeping with the glorious record of

our colored troops in our former wars.

- 3. This letter is to be read confidentially

to the troops immediately upon its receipt and made available in Orderly

Rooms. Every assistance must

be promptly given qualified men to volunteer for this service.6

-

- Two days later the formal plan,

based on General Davis' conference with the GFRC staff, went out to commanders.

It provided that the initial quota of volunteers be kept to 2,000, the largest

number the GFRC could handle at once and a number which would not reduce

any service unit by more than 3.5 percent at the most. Personnel with the

highest qualifications would get first priority and no man with an Army

General Classification Test score lower than Grade IV would be taken. The

number of volunteers would be reported by 9 January 1945 so that quotas

could be allocated to units. The men selected were to report to the 16th

Reinforcement Depot at Compiegne not later than 10 January 1945. They would

be relieved from their present units and attached unassigned to the Ground

Force Reinforcement Command. The retrained personnel would then be assigned

to combat units as infantry reinforcements without regard to race.7

-

- Before the plan could be carried

out, a number of changes, some resulting from misunderstanding and others

from apprehension, occurred. The plan itself represented a major break with

traditional Army policy, for it proposed mixing Negro soldiers into otherwise

white units neither on a quota nor a smaller unit basis but as individuals

fitted in where needed. When the cir-

- [689]

- cular letter to troops reached Supreme

Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), Lt. Gen. Walter B. Smith,

chief of staff, held that its promise to assign Negro troops "without

regard to color or race to the units where assistance is most needed, and

give you the opportunity of fighting shoulder to shoulder to bring about

victory" was a clear invitation to embarrassment to the War Department.

Failing to convince General Lee that he should change his letter, he put

the matter to General Eisenhower:

-

- Although I am now somewhat out of

touch with the War Department's negro policy, I did, as you know, handle

this during the time I was with General Marshall. Unless there has been

a radical change, the sentence which I have marked in the attached circular

letter will place the War Department in very grave difficulties. It is inevitable

that this statement will get out, and equally inevitable that the result

will be that every negro organization, pressure group and newspaper will

take the attitude that, while the War Department segregates colored troops

into organizations of their own against the desires and pleas of all the

negro race, the Army is perfectly willing to put them in the front lines

mixed in units with white soldiers, and have them do battle when an emergency

arises. Two years ago I would have considered the marked statement the most

dangerous thing that I had ever seen in regard to negro relations.

-

- I have talked with Lee about it,

and he can't see this at all. He believes that it is right that colored

and white soldiers should be mixed in the same company. With this belief

I do not argue, but the War Department policy is different. Since I am convinced

that this circular letter will have the most serious repercussions in the

United States, I believe that it is our duty to draw the War Department's

attention to the fact that this statement has been made, to give them warning

as to what may happen and any

facts which they may use to counter the pressure which will undoubtedly

be placed on them.

-

- Further, I recommend most strongly

that Communications Zone not be permitted to issue any general circulars

relating to negro policy until I have had a chance to see them. This is

because I know more about the War Department's and General Marshall's difficulties

with the negro question than any other man in this theater, including General

B. O. Davis whom Lee consulted in the matter-and I say this with all due

modesty. I am writing this as I may not see you tomorrow morning. Will talk

to you about it when I return.8

-

- General Eisenhower personally rewrote

the directive, changing all but the first two sentences and making dissemination

permissive instead of mandatory. "This is replacing the original &

is something that can not possibly run counter to regs in a time like this,"

he told General Smith.9

The new directive, officially approved by both General Eisenhower and General

Lee, appeared over General Lee's signature with the same date, file number,

and subject as the earlier directive, under a cover letter ordering return

and destruction of all copies of the original version. The substitute letter

read:

-

- 1. The Supreme Commander desires

to destroy the enemy forces and end hostilities in this theater without

delay. Every available weapon at our disposal must be brought to bear upon

the enemy. To this end the Theater Commander has directed the Communications

Zone Commander to make the greatest possible use of limited service men

within service units and to

- [690]

- survey our entire organization in

an effort to produce able bodied men for the front lines. This process of

selection has been going on for some time but it is entirely possible that

many men themselves, desiring to volunteer for front line service, may be

able to point out methods in which they can be replaced in their present

jobs. Consequently, Commanders of all grades will receive voluntary applications

for transfer to the Infantry and forward them to higher authority with recommendations

for appropriate type of replacement. This opportunity to volunteer will

be extended to all soldiers without regard to color or race, but preference

will normally be given to individuals who have had some basic training in

Infantry. Normally, also, transfers will be limited to the grade of Private

and Private First Class unless a noncommissioned officer requests a reduction.

- 2. In the event that the number

of suitable negro volunteers exceeds the replacement needs of negro combat

units, these men will be suitably incorporated in other organizations so

that their service and their fighting spirit may be efficiently utilized.

- 3. This letter may be read confidentially

to the troops and made available in Orderly Rooms. Every assistance must

be promptly given qualified men who volunteer for this service.10

-

- The new letter allowed for further

changes in the initial plan for individual replacements but the revision

appeared too late to halt the distribution of the first version completely.

The Normandy Base Section, for example, had already distributed the earlier

letter to the commanders of all Negro units on 28 December and had sent

copies to both of its districts.11

-

- The revised letter could be interpreted

in a number of ways. There were no Negro infantry units in the theater.

The theater had long been concerned with replacements for its Negro artillery,

tank, and tank destroyer units, for it had already been told that none would

be available from the United States. If Negro volunteers from service units

were to be retrained for combat use, the greatest immediate need was in

units like the 761st Tank and 3334 Field Artillery Battalions whose losses

without replacements threatened their combat efficiency and, in the case

of the 333d threatened their existence. The revised letter seemed to direct

that Negro volunteers would first be used for these units. But the GFRS

was not equipped to convert individuals to any service other than infantry

and the smaller Negro combat support units were already operating under

a system, admittedly not the happiest solution, of retraining their own

replacements from volunteers and replacements trained in other branches.

Since the revised letter could still be interpreted to mean that any excess

Negro volunteers would be placed in white units in the same manner as white

reinforcements, SHAEF G-1 pressed for a further clarification. After determining

that General Eisenhower did not desire to place Negro trainees in white

organizations as individuals and that he preferred to form the Negro trainees

into "units which could be substituted for white units in order that

white units could be drawn out of line and rested," SHAEF G-1 prepared

a new letter directing that the Negro volunteers be trained as reinforcements

for existing Negro combat units in the theater and that any excess

- [691]

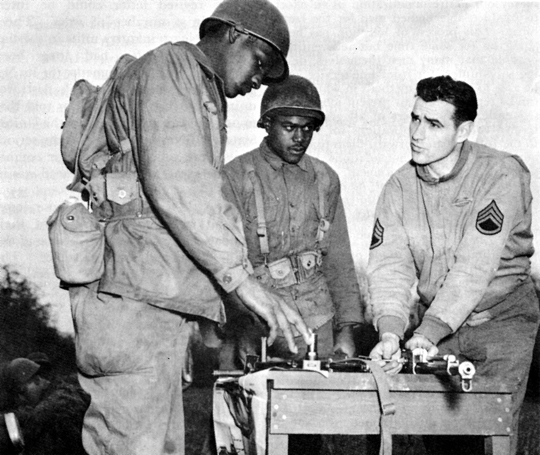

- VOLUNTEERS FOR COMBAT INFANTRY

REPLACEMENT

- learning how to assemble a BAR.

-

- be formed into separate infantry

units for assignment to an army group. Initially, the goal would be one

battalion; subsequently, if numbers warranted, this battalion would be expanded

to a regiment. All other instructions were rescinded.12

-

- Originally, "in fairness to

all concerned," this new directive was to be sent to all Negro units

to interpret paragraph 2 of the revised letter of 26 December. After further

discussions, distribution was confined to the theater G-3 and G-4, to the

Commanding General, GFRC, and to General Davis. It went out under a covering

letter indicating that it was an interpretation of the words "other

organizations" in the revised December letter.13

The change

- [692]

- in plan did not, therefore, reach

Negro troops during the period of volunteering.

-

- By February, 4,562 Negro troops

had volunteered, many of the noncommissioned officers among them taking

reductions in rank to do so.14

The first 2,800 reported to the Ground Force Reinforcement Command in January

and early February, after which the flow of volunteers was stopped. The

service units from which these men came parallelled closely the distribution

of Negroes by branch: 38 percent came from engineer units, 29 percent from

quartermaster, 26 percent from transportation, 9 percent from signal, 2

percent from ordnance, and the remaining 2 percent from units of other branches.

Sixty-three percent had formerly had one of the six following military occupational

specialties, in order of frequency: truck driver, duty soldier, longshoreman,

basic, construction foreman, and cargo checker. Like other volunteers, they

were somewhat younger than average-10 percent of the Negro riflemen were

thirty years old or older as compared with 20 percent of white riflemen.

They had somewhat better educational backgrounds and test scores than the

average for Negro soldiers in the European theater but the differences between

them and other Negro troops in these respects were not so great as the differences

between them and the average white troops. Of the white riflemen in the

ETO, 41 percent were high school graduates and 71 percent were in AGCT classes

I, II, and III; of the Negro infantry reinforcements, 22 percent were

high school graduates and 29 percent

were in classes I, II, and III; of all Negroes in ETO, 18 percent were high

school graduates and 17 percent were in Classes I, II, and III.15

The important difference between these soldiers and other Negro troops was,

therefore, that they had volunteered on the basis of a call to duty under

circumstances unusual to their former Army experience. Only their motivation

and their method of employment set them off sharply from other Negro troops.

-

- Retraining was conducted at the

16th Reinforcement Depot at Compiegne, which had been retraining individuals

as riflemen since November. The Negro trainees were organized into the 47th

Reinforcement Battalion, 5th Retraining Regiment, under the command of Col.

Alexander George. According to the depot staff, the Negro volunteers approached

their work with a will. There were proportionately fewer absentees and fewer

disciplinary problems among the Negro trainees than among the white soldiers

being retrained as infantrymen.16

-

- The question of how to carry out

the latest directive on the completion of the training of these infantrymen

arose toward the end of January 1945. The Ground Force Reinforcement System

was equipped to train individual replacements only; the newer provision

that Negro trainees in excess of those needed in combat support units be

trained as a battalion could not be met

- [693]

- 47TH REINFORCEMENT BATTALION

- trainees march out for a day

of intensive training, Noyon, France, February 1945.

-

- by the system. In the meantime,

command of the system changed and responsibility for it shifted from General

Lee's Communications Zone to Lt. Gen. Ben Lear, newly arrived in the theater

as deputy theater commander. General Lee now obtained a new interpretation

of General Eisenhower's wishes and passed them on to General Lear. General

Lee reminded General Lear that the army commanders and General Eisenhower

had personally approved the original plan with the understanding that the

men so trained would be used in infantry units. He informed General Lear

that General Eisenhower "now desires that these colored riflemen reinforcements

have their training completed as members of Infantry rifle platoons familiar

with the Infantry rifle platoon weapons." These platoons would be made

available to army commanders who would then provide platoon leaders, platoon

sergeants, and, if necessary, squad leaders. "It is my feeling,"

General Lee said, "that we should afford the volunteers the full opportunity

for Infantry riflemen service. Therefore we should not assign: them as Tank

or Artillery reinforcements unless they express such preference. To do otherwise

would be breaking faith, in my opinion."17

-

- The Reinforcement Command had enough

volunteers to form 45 to 47 platoons, including overstrength provided to

compensate for the expected lack of further reinforcements for these units.

- [694]

- The first 2,253 men were ready by

I March. They were organized into 37 platoons: 25 went to 12th Army Group

and 12 to 6th Army Group, joining about to March. A second group was distributed

later, 12 platoons going to 12th Army Group and 4 to 6th Army Group. The

divisions sent one platoon leader and one sergeant to meet each platoon

at the 16th Depot. The possibility of receiving needed replacements, especially

in early March when the spring offensive and the crossing of the Rhine were

in the offing, was readily accepted by most divisions. Army group and army

commanders were given discretion in the use of the platoons. They could

be assigned to divisions as platoons or they could be assigned in larger

groupings. They could later be grouped into units as large as a battalion

if so desired.18

-

- In 12th Army Group the platoons

were assigned to divisions in groups of three and the divisions, retaining

them as platoons, usually assigned one to each regiment. The regiments,

in turn, selected a company to which the units went as a fourth rifle platoon.19

-

- In most divisions, the platoons

were given additional training periods of varying lengths before commitment.

In others, such as the divisions headed across the Remagen Bridge, the platoons

arrived just in time for immediate employment. Where arrival of the Negro

platoons coincided with a period of heavy fighting, their welcome as fresh

replacements was warmer than in units that were then engaged in training

only.20

But divisional training periods were valuable both to the platoons and to

the divisions' attitude toward accepting them. "They had had some sort

of training before they joined us," one assistant division commander

explained, "but we wanted to make sure they knew all the tricks of

infantry fighting. We assigned our best combat leaders as instructors. I

watched those lads train and if ever men were in dead earnest, they were."21

In some cases the platoons were given the division patch and a brief indoctrination

in the division's history and accomplishments, plus personal welcomes by

the division or assistant division commander.22

-

- In most instances, the platoons

quickly identified themselves with the more than three dozen battalions

and companies to which they were distributed. They were employed just as

any other platoon within their companies, a point frequently noted by their

regiments. Some went to veteran regiments which, like those of the 1st and

9th Divisions, had fought in Europe and Africa. Others went to newer units

like the 12th and 14th Armored Divisions, and the 69th, 78th, 99th, and

104th In-

- [695]

- fantry Divisions. These divisions

played varying roles in the concluding months of the war. Some still met

hard fighting in their marches across the Rhine and across central Germany;

others found resistance collapsing all around them and spent the last weeks

of the war rounding up the enemy and establishing provisional military governments.

-

- Army and theater headquarters were

considerably more interested in the careers of the platoons than were the

units which, having accepted them, proceeded to employ them as they -would

have any other platoons. Selected divisions were required to report weekly

on the strength and casualties of the platoons-their casualties were usually

proportionate and in some instances relatively higher than those of comparable

platoons in the same unit. Division G-1's were initially concerned about

grades and promotions for the members of the platoons, many of which had

arrived with all of their members rated as privates and privates first class.

Strenuous efforts to determine whether the platoons had their own tables

of organization with authorized ratings or whether the Negro riflemen were

eligible for promotion within the tables of organization of their units

and whether their members were eligible for officer candidate quotas was

a question of concern both to the Reinforcement System and to the divisions.

Army headquarters determined that the platoons would be assigned noncommissioned

grades, a procedure considered only fair now that the Negro riflemen were

not to be integrated individually, but in most instances authority for these

promotions did not arrive in time to affect the organization of the platoons.

Most of the platoons, including those organized as provisional companies

with the armored divisions, finished the war without ratings.

-

- At the close of the first calendar

month after the platoons joined their units, divisions had already formed

their impressions of the Negro replacements. The 104th Division, whose platoons

had joined while the division was defending the west banks of the Rhine

at Cologne, commented: "Their combat record has been outstanding. They

have without exception proven themselves to be good soldiers. Some are being

recommended for the Bronze Star Medal."23

When General Davis stopped at 12th Army Group headquarters on his way to

observe the platoons a month after they had joined their units, he found

that General Bradley was well satisfied with the reports of the performance

and conduct of the Negro reinforcements. General Hodges stated that First

Army's divisions had given excellent reports on their Negro platoons. As

General Davis went down through corps and division to regiment and battalion

and finally to a company-Company E of the Goth Regiment, 9th Infantry Division-he

found similar reports of satisfaction. At Company E, the company and platoon

commanders and several enlisted men, including the white platoon sergeant,

recounted their experiences with enthusiasm. All officers and men, from

the regimental commander down, reported high morale and confirmed that the

platoon was functioning as planned.24

-

- The 60th Infantry's Negro platoon

had

- [696]

- had its first heavy going less than

a fortnight before, on 5 April, when it and the other platoons of its company

took Lengenbach. "This was the colored troops' first taste of combat,"

the regiment's combat historian recorded, "and they took a big bite."25

Four days later one of these men, Pfc. Jack Thomas, won the Distinguished

Service Cross for leading his squad on a mission to knock out an enemy tank

that was providing heavy caliber support for a hostile roadblock. Thomas

deployed his squad and advanced upon the enemy position. He hurled two hand

grenades, wounding several of the enemy. When two of his men at a rocket

launcher were wounded, Thomas took up the weapon and launched a rocket at

the Germans, preventing them from manning their tank. He then picked up

one seriously wounded member of the rocket launching team and, through small

arms and automatic weapons fire, carried him to safety.26

-

- Officers and men in other divisions

gave General Davis similar reports of their satisfaction with the Negro

reinforcements. One division commander, Maj. Gen. Edwin F. Parker of the

78th Division, whose Negro platoons, joining at the Remagen bridgehead,

were the first Negro combat troops east of the Rhine, expressed the wish

that he could obtain more of the Negro riflemen.27

The 104th Division's G-1 noted that he gave

General Davis a very satisfactory report.28

He told the visiting general:

-

- Morale: Excellent. Manner of performance:

Superior. Men are very eager to close with the enemy and to destroy him.

Strict attention to duty, aggressiveness, common sense and judgment under

fire has won the admiration of all the men in the company. The colored platoon

after initial success continued to do excellent work. Observation discloses

that these people observe all the rules of the book. When given a mission

they accept it with enthusiasm, and even when losses to their platoon were

inflicted the colored boys accepted these losses as part of war, and continued

on their mission. The Company Commander, officers, and men of Company "F"

all agree that the colored platoon has a calibre of men equal to any veteran

platoon. Several decorations for bravery are in the process of being awarded

to the members of colored platoons.29

-

- The three platoons attached to the

three regiments of the 1st Infantry Division illustrate the range and circumstances

of employment of Negro reinforcements within a single division. The 26th

Infantry's platoon, continuously engaged from 12 March to 8 May, varied

in strength from 36 to 31 men. They took their turn at every assignment

within their company: patrolling, outposting, assault platoon, support platoon

in attacks, and platoon in defense. While little time was available for

training-the platoon upon arrival had had individual training only-the regiment

estimated that combat efficiency went up

- [697]

- from 30 percent to an estimated

8o percent by the end of the second week, a development which the regiment

ascribed to an "increase in confidence and training brought about by

joint integrated action in combat." 30

Efficiency increased further in the next weeks and the platoon took its

"full share of this almost continuous fighting and maneuvering."31

Replacements kept this platoon operating as an entity, but the platoon assigned

to Company B, 16th Infantry, had thirty men wounded and nine killed in action,

with the result that on V-E Day it had only fifteen men present for duty.

When its platoon strength fell too low to operate as a platoon the Negro

riflemen were used as a squad or squads in a white platoon. Company B's

Negro reinforcements participated in every battle from 12 March to 8 May.

In their first action, they were "over-eager and aggressive" and

consequently suffered severe casualties. Despite their casualties, their

success in battle was good and they took their assigned objectives in an

aggressive manner. White platoons "like[d] to fight beside them because

they laid a large volume of fire on the enemy positions." Their discipline

was good. They had only "three or four" minor company punishments

under the 104th Article of War and no courts-martial offenses.32

The platoon with Company B, 18th Infantry, had a strength varying from 20

to 43 men. It, too, was employed "in an identical manner

to any other rifle platoon in the regiment," and, from its first contact

with the enemy on 18 March near Eudenbach in the Remagen bridgehead, it

participated in all company combat engagements until hostilities ceased.

The aggressiveness of this platoon was both an asset and a drawback, for

at times it overran objectives and became overextended. Despite a "slightly

more pronounced" nervousness when subjected to shell fire when in defense

at night, the record of its men "as a whole in combat was very satisfactory

and the platoon can most certainly be considered a battle success."33

When this platoon's white sergeant was wounded, he was replaced by a Negro

who performed "all the duties of a platoon sergeant, in and out of

combat, in a superior manner." 34

From another division came similar reports. The Negro platoons of the 99th

Division, characterized as employed "just as any other platoon,"

-

- . . . performed in an excellent

manner at all times while in combat. These men were courageous fighters

and never once did they fail to accomplish their assigned mission. They

were particularly good in town fighting and [were often used as the assault

platoon with good results. The platoon assigned to the 3934 Infantry is

credited with killing approximately too Germans and capturing 900. During

this action only three of their own men were killed and fifteen wounded.35

-

- Units, in their own unofficial accounts,

were more laconic. For example, the 393d's platoon, in the regiment's photographic

history for its men, was described

- [698]

- as "The Colored Platoon of

Easy Company-one of the best platoons in the regiment." 36

-

- There was less satisfaction with

the Negro riflemen assigned to the Seventh Army. The 6th Army Group and

Seventh Army had not been included in the original discussions of the use

of Negro riflemen. On the decision of General Patch, the twelve platoons

assigned to Seventh Army were organized into provisional companies and sent

to the 12th Armored Division, whose armored infantry battalions had relatively

greater shortages than infantry division regiments. The platoons, barely

trained as squads and platoons, had had no training as companies at all;

the division felt that too little time was available to equip and train

them before their first battle. 37

The 12th Armored Division, after its experience with the 827th Tank Destroyer

Battalion a month before-it received notification to send officers to these

platoons on the day that the 827th departed-"objected violently"

to these platoons from the beginning. But when the reinforcements arrived

they made a "good" impression.38

The 12th Armored Division's companies were known variously as Seventh Army

Provisional Infantry Companies 1, 2, and 3, or as Company D in each of the

armored infantry battalions to which they were attached.39

All of these companies were used as armored infantry in support of tanks

or with tank support, but their organization

varied. One was composed of four platoons, each organized into one machine

gun and three rifle squads. The other two had three platoons, each with

two 60-mm. mortars and several light machine guns. The companies attacked

dismounted or mounted on tanks; all engaged in several actions. They were

generally considered very satisfactory, improving as experience made up

for their lack of training as companies and as machine gun and mortar crews.40

When 6th Army Group's four supplementary platoons arrived on 26 March, they

were similarly assigned to the 14th Armored Division, which took them with

it when it moved to Third Army on 23 April.41

In the 14th Armored Division, they were known as Seventh Army Provisional

Infantry Company No. 4 or, since they were attached to the Combat Command

Reserve, as CCR Rifle Company.42

-

- When General Davis visited the 12th

Armored Division on 1 9 April 1945, he found battalion and company commanders

acutely conscious of the lack of company training in the Negro platoons.

Even so, they felt that the units had done good work.43

Seventh Army Provisional Infantry Company No. 1, attached to the 56th Armored

Infantry Battalion, had not been committed as a unit but detachments had

been used. One of these, riding on a tank near Speyer, Germany, on 23 March

1945,

- [699]

- ran into heavy bazooka and small

arms fire. Sgt. Edward A. Carter, Jr., voluntarily dismounted and attempted

to lead a three-man group across an open field. Within a short time, two

of his men were killed and the third was seriously wounded. Carter continued

toward the enemy emplacement alone. He was wounded five times and was finally

forced to take cover. When eight enemy riflemen attempted to capture him,

Carter killed six of them and captured the remaining two. He then returned

across the field, using his two prisoners as a shield, obtaining from them

valuable information on the disposition of enemy troops.44

-

- Similarly, the 240-man company attached

to the 14th Armored Division, in combat from 5 April to 3 May 1945, failed

to receive the same approving response from the division as the platoons

attached to infantry regiments.45

The 14th Armored Division, moving south through Bavaria along the Bayreuth

Nurnberg autobahn when everyone knew that the war was over, that is everyone

"except the men who could hear the high-pitched, irritable whine of

a sniper's bullet, the blast of a mortar shell,"46

met sporadic and spotty resistance, but resistance that was still strong

enough to produce sharp, and sometimes prolonged, fire fights. The Combat

Command Reserve rifle company was mainly

employed in attachment to the 25th Tank Battalion. The company's first real

engagement was at Lichtenfels, where two platoons crossed the Main and,

after a bitter fight, took the town.47

But it was at Creussen, near Bayreuth that the Negro reinforcements got

the accolade of approval from the men of the 14th Armored Division. The

94th Reconnaissance Squadron had entered Creussen, site of a weapons factory,

on 15 April when enemy tanks and infantry all but surrounded the town. A

call for reinforcements started two platoons of tanks from the 25th Tank

Battalion and one of the Negro infantry platoons toward the town. At about

1145, near Gottsfeld, the tanks were fired on by antitank guns. Four were

hit and two were destroyed. The remaining tanks pulled back. The Negro infantrymen

dismounted, entered the town, and, while considerable enemy artillery fire

fell, cleared Gottsfeld by 1500. Tanks then moved in and before dark knocked

out five enemy Mark IV's which had come out into the open just east of the

town. The tank-infantry force then continued to Creussen, already relieved

of much pressure as a result of the action at Gottsfeld, and moved in from

the west at 1700. For the next two days, platoons of Combat Command Reserve

rifle company patrolled in and around Gottsfeld and Creussen, taking prisoners.

One platoon of the 94th's D Troop, observing the Negro riflemen for the

first time, commented in its journal: "And were those guys good! "48

In later fighting, when the company (less one platoon) was used as a unit,

results were

- [700]

- less satisfactory. Poor control

and discipline within the companies, especially after taking towns, was

the principal fault that Seventh Army found with its Negro units.

-

- When General Patch informed General

Davis that the provisional companies were not trained to function as companies

and were not performing too well as armored infantry, General Davis explained

that they were never intended to be used as other than riflemen, and that,

except for a week before assignment, they had had no group training. He

described the use being made of them in First Army. He himself had noted

that the men in the Seventh Army's companies, though they stated that they

were getting along fine, lacked the enthusiasm and high morale of the Negro

reinforcements in the First Army.

-

- When General Davis' report of his

visit reached General Devers, with an informal recommendation from General

Lear that it should receive any action thought suitable, General Devers

sent it on to General Patch with a note for his consideration to the effect

that "a better solution would have been to use them as rifle platoons

in an Infantry Division." Maj. Gen. Roderick Allen, commanding the

12th Armored Division, was scheduled to visit General Patch on 12 May to

discuss the matter, but by then the war was over. General Patch informed

his chief of staff on 11 May: "Nothing more need be done. Already Allen

will be giving them Co. Tng."'49

-

- Thus, among men similarly trained

and similarly motivated, two forms of employment

produced different results -at least in the eyes of higher headquarters

if not in the eyes of the men and their immediate associates, who had no

means of comparison. All the men were volunteers, and had identical training.

But the men in the larger units, organized as companies with their own company

administration, adding to the duties of riflemen in which they were trained

those of machine gunners and mortar men in which they were not trained,

operating as separate and provisional units obviously attached and not a

part of the units with which they fought, lost a portion of their original

enthusiasm and motivation in the process of commitment to battle. The smaller

groups-operating as platoons and at times as squads-as parts of the companies

to which they were attached, gained in their commitment. This was not achieved

without skepticism on the part of both the Negro replacements and their

associates within their companies. An officer who, as rifle platoon and

company commander, led one of these platoons for nearly two months, explained

that his platoon, advancing at mid-day through heavy woods, in its very

first contact with the enemy

-

- . . . discovered a German force

digging in upon a hill-top. Without being discovered, it maneuvered into

a position to deliver maximum fire from a distance of a scant 20 yards,

and struck so powerfully and suddenly that the Germans were shot-up and

dispersed before they could pick up their weapons-2 machine guns, 4 machine

pistol "burp guns," several rifles and dozens of grenades.

-

- A lucky break, we all agreed ....

-

- But the soldiers of this platoon

showed thereafter that this was not simply "a lucky break" since

in "frequent instances

- [701]

- after that baptismal triumph"

their fellow white soldiers saw them "prove their stuff at the cost

of lives and blood by advancing doggedly under fire, by aggressive noncommissioned

officer leadership in house-to-house fights and in the forbidding wilderness

of No-Man's Land."50

As the men of this platoon took their places in their company, not a single

incident of friction occurred between them and the white infantrymen who

fought for the same towns, ate in the same chow line, sometimes gambled

in the same clandestine games. The Negro troops of this platoon gradually

came to be accepted not as unusual, or special, but as normal soldiers,

neither better nor worse than usual. "The premise that no soldier,"

their commander decided, "will hold black skin against a man if he

can shoot his rifle and does not run away proved to be substantially true.

Most of the white men of the company soon became highly appreciative of

the Negroes' help and warmly applauded their more colorful individual and

combat exploits."51

-

- One Negro platoon, when faced with

heavy automatic weapons fire from outlying buildings in a town which another

platoon was already supposed to have taken, made a hasty estimate of the

situation and, realizing that its only safety was in the buildings from

which its men were receiving fire, broke into a run with all weapons firing,

raced three hundred yards under "a hail of enemy fire," took the

buildings and, in a matter of minutes, the entire town. The battalion commander

concluded:

-

- I know I did not receive a superior

representation of the colored race as the average AGCT was Class IV. I do

know, however, that in courage, coolness, dependability and pride, they

are on a par with any white troops I have ever had occasion to work with.

In addition, they were, during combat, possessed with a fierce desire to

meet with and kill the enemy, the equal of which I have never witnessed

in white troops.

-

- In a number of units whose praise

of the willing efforts of the Negro volunteers during combat was high there

arose an undercurrent of misgivings about retaining these troops within

units once the war was over and battalions and regiments settled into occupation

and garrison duties. But in this battalion two months of garrison life had

brought no deterioration of relations between Negro and white soldiers:

-

- To date, there has never appeared

the slightest sign of race prejudice, or discrimination in this organization.

White men and colored men are welded together with a deep friendship and

respect born of combat and matured by a realization that such an association

is not the impossibility that many of us have been led to believe. Segregation

has never been attempted in this unit, and is, in my mind, the deciding

factor as to the success or failure of the experiment. When men undergo

the same privations, face the same dangers before an impartial enemy, there

can be no segregation. My men eat, play, work, and sleep as a company of

men, with no regard to color. An interesting sidelight is the fact that

the company orientation NCO is colored, the pitcher on the softball team,

composed of both races, is colored, and the bugler is colored.

-

- The sole morale problem facing these

troops two months after the conclusion of hostilities was the growing suspicion,

now that a group of Negro troops had

- [702]

- been transferred to this unit from

another division, that they too would "soon be removing their Division

patch, and the thought of this impending separation has materially affected

their morale and performance thereby."52

-

- This was a morale problem to many

of the Negro reinforcements, for as redeployment regulations went into effect,

the Negro infantrymen, having fewer points than the white troops in their

units, began to be transferred to other units, including a large group that

went to a combat engineer battalion constructing redeployment camps. The

suspicion arose that all would eventually be returned to service units.

Actually a compromise was worked out by the European theater, which declared

that it could not make exceptions to redeployment regulations. A thousand

or more of the reinforcements with relatively higher points were sent to

the 69th Infantry Division for redeployment to the United States and the

remainder, except for some who, having been transferred already, could not

be readily located, went to the 350th Field Artillery Battalion, a Negro

unit of low redeployment status, thus preserving their combat status and

at the same time remaining with the occupation forces in Europe. The compromise

was not wholly satisfactory to the troops concerned, for most of them had

hoped to remain with the units with which they had fought and with whose

men they had got along well. Many had hoped that their service would be

"the beginning of the end of differences and discriminations on

account of race and color."53

As one of their commanders explained their and his dilemma: "These

colored men cannot understand why they are not being allowed to share the

honor of returning to their homeland with the Division with which they fought,

proving to the world that Negro soldiers can do something besides drive

a truck or work in a laundry. I am unqualified to give them a satisfactory

answer."54

-

- In the Negro infantry rifle platoons,

the employment of Negro troops moved farthest from traditional Army patterns.

Despite the multitude of problems with which the Army was faced in the use

of Negro troops in World War II, at the war's end a greater variety of experience

existed than had ever before been available within the American Military

Establishment. For Negro troops had been used in larger numbers over a longer

period of time than in any previous war. They had been used by more branches

and in a greater variety of units, ranging from divisions to platoons in

size and from fighter units to quartermaster service companies in the complexity

of their duties. They had been used in a wider range of geographical, cultural,

and climatic conditions than was believed possible in 1942. All of this

was true of white troops as well, but in its manpower deliberations and

in its attempts to wrest maximum efficiency and production from the manpower

allotted it, the Army found that it was the

- [703]

- 10 percent of American manpower

which was Negro that spelled a large part of the difference between the

full and wasteful employment of available American manpower of military

age.

-

- As World War II drew to a close

the Army, as a part of its continuing inventory of its operations, turned

fuller attention to the problems of Negro manpower. These had already received

disproportionate administrative attention hardly justified by the results.

The Army was now interested in the experience of the theaters, both to conclude

the war in the Pacific and to plan for the postwar Army. Reports and more

reports already existed, but the Army was now interested in the judgment

of the theaters themselves. For whatever had occurred in the training and

deployment phases, the crucial questions could be answered best by the experience

of the theaters-the experience with Negro troops at the point of operational

use. Before the war was over, stock-taking on the employment of Negro troops

in World War II had already begun. Upon the basis of the direct experience

of the war, the McCloy Committee began to look toward the establishment

of a clearer postwar policy than there had ever been. Shortly after the

war was over, on 4 October 1945" the War Department appointed a board

of officers, headed by Lt. Gen. Alvan C. Gillem, Jr., to prepare a new and

broad policy for the future employment of Negro troops. From the investigations

and conclusions of this committee many of the changes in the employment

of Negro troops after World War II would come. These deliberations and developments

belong properly to a study of the postwar period, although the genesis

- of the change may be found in the

vastly varied experiences of the Army and the War Department in the employment

of Negro troops in World War II.

-

- Writing in the early summer of 1945,

before the fighting with Japan ended, the Chief Historian of the Army, the

late Dr. Walter L. Wright, Jr., provided a perceptive commentary on the

Army's experience with the employment of Negro troops in segregated units

during World War II: 55

-

- With your general conclusion regarding

the performance of Negro troops, I tend to agree: They cannot be expected

to do as well in any Army function as white troops unless they have absolutely

first-class leadership from their officers. Such leadership may be provided,

in my opinion, either by white or by Negro officers, but white officers

would have to be men who have some understanding of the attitude of mind

which Negroes possess and some sympathy with them as human beings. What

troubles me is that anybody of real intelligence should be astonished to

discover that Negro troops require especially good leadership if their performance

is to match that of white troops. This same state of affairs exists, I think,

with any group of men who belong to a subject nationality or national minority

consisting of under-privileged individuals from depressed social strata

.... American Negro troops are, as you know, ill-educated on the average

and often illiterate; they lack self-respect, self-confidence, and initiative;

they tend to be very conscious of their low standing in the eyes of the

white population and consequently feel very little motive for aggressive

fighting. In fact, their survival as individuals and as a people has often

depended on their ability to subdue completely even the appearance of aggressiveness.

After all, when a man knows that the color of his skin will automatically

disqualify him for reaping the fruits of attainment it is no wonder that

he sees

- [704]

- little point in trying very hard

to excel anybody else. To me, the most extraordinary thing is that such

people continue trying at all.

-

- The conclusion which I reach is

obvious: We cannot expect to make first-class soldiers out of second or

third or fourth class citizens. The man who is lowest down in civilian life

is practically certain to be lowest down as a soldier. Accordingly, we must

expect depressed minorities to perform much less effectively than the average

of other groups in the population .... So far as the war in progress is

concerned, the War Department must deal with an existing state of affairs

and its employment of Negroes must parallel the employment of the same group

in civilian American society. Yet, it is important to remember that the

civilian status of Negroes in this country is changing with a rapidity which

I believe to be unique in history; the level of literacy is rising steadily

and

- quickly and privileges other than

educational are being gained every year ....

-

- As to the segregation of Negroes

to special units in the Army, this is simply a reflection of a state of

affairs well-known in civilian America today. Yet, civilian practice in

this connection differs very widely from Massachusetts to Mississippi. Since

the less favorable treatment characteristic of southern states is less likely

to lead to violent protest from powerful white groups, the Army has tended

to follow southern rather than northern practices in dealing with the problem

of segregation. Also, it is most unfortunate for the Negroes that considerations

of year round climate led to the placing of most of the training camps in

the southern states where conditions in the nearby towns were none too acceptable

to northern white men and the unfamiliar Jim Crowism was exceedingly unacceptable

to northern Negroes. My ultimate hope is that in the long run it will be

possible to assign individual Negro soldiers and officers to any unit in

the Army where they are qualified as individuals to serve efficiently.

-

- Within a decade, this hope was to

be realized.

- [705]