In a valedictory letter to

President Truman on 18 Novem-

[217]

ber 1952 Secretary of Defense

Robert A. Lovett commented on the difficulties he had had in asserting

effective control over supply matters because "certain ardent

separatists occasionally pop up with the suggestion that the Secretary

of Defense play in his own back yard and not trespass on their

separately administered preserves."

There are seven technical

services in the Army . . . . Of these seven technical services, all are

in one degree or another in the business of design, procurement,

production, supply, distribution, warehousing and issue. Their functions

overlap in a number of items, thus adding substantial complication to

the difficult problem of administration and control.

It has always amazed me that the

system worked at all, and the fact that it works rather well is a

tribute to the inborn capacity of team-work in the average American...

A reorganization of the

technical services would be no more painful than backing into a buzz

saw, but I believe that it is long overdue.1

Explaining the lack of progress

in carrying out the financial reforms called for in the National

Security Act amendments of 1949, Lovett told a Congressional

investigating committee that it was very difficult to obtain accurate

statistics from the Army's technical services. Adequate supply control

was impossible at that level, he said, because a single depot might

receive its funds from fifty or a hundred sources. The basic problem, he

said, was the resistance of the technical services and the Army's

General Staff to change combined with a natural dislike of outsiders

trespassing on their preserves of authority. All this had led to a

"mental block," he maintained, in some of the services against

financial reforms.2

Karl R. Bendetsen, an attorney

and former Under Secretary of the Army, submitted a proposal to

Secretary Lovett in October 1952 for reorganizing the Army and the

technical services along functional lines. The weakness of previous

reorganizations, he said, had been that they treated symptoms instead

of attacking the basic issue, the Army's fragmented field organization

where seven major commands were each involved in buying, mechandizing,

warehousing, distributing, and even

[218]

research and development. They

were "virtually self-contained" autonomous commands, each with

its own personnel and training systems, no matter what its designation

might be as part of the Army staff. He could not identify any consistent

functional pattern in their arrangement. They were organized rather on

a professional basis with civil engineers, electrical engineers, and

mechanical engineers in separate commands. There was fragmentation and

duplication of effort in research and development and no effective means

of bringing the user, the combat soldier, into the picture. Disagreement

among the technical services forced the General Staff, particularly G-4,

to intervene in matters for which it lacked both the staff and authority

to act. The continental Army commands followed different personnel

policies and procedures, forcing G-1 into personnel operations of the

Army although it lacked the necessary staff. There was the

administrative chaos and friction created by housekeeping functions,

especially repairs and utilities, performed for technical service

installations by local Army commanders. Here again disagreement forced

administrative details "which have no business in the

Pentagon" to the top.

To provide more effective

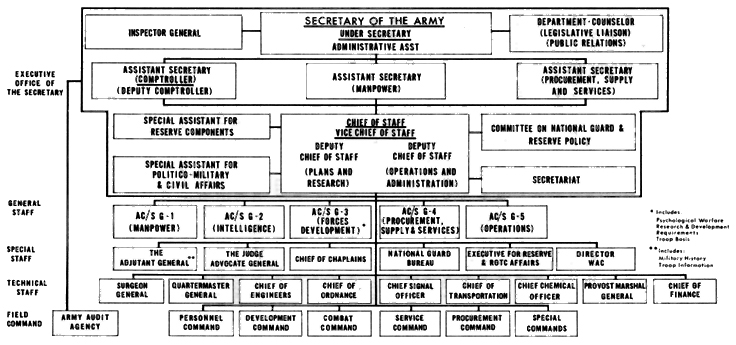

management Mr. Bendetsen proposed to reorganize the Army from the bottom

up, replacing the continental armies with seven nationwide functional

commands, using the Secretary's new authority to distribute nonmilitary

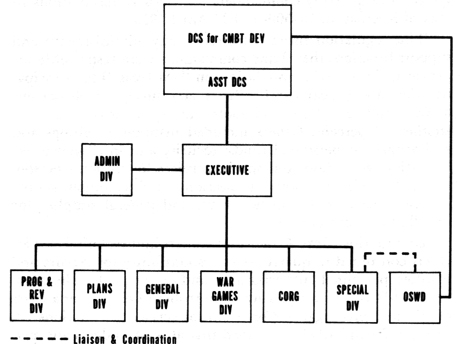

functions within the Army as he saw fit. (Chart 19)

A Personnel Command would be

responsible for all personnel operations in the Army, including

manpower procurement, induction of draftees, replacement training

centers, prisoner of war camps, and disciplinary barracks. It would

provide

basic training for individuals. A Combat Command would take up where the

Personnel Command left off, concentrating on organizational training and

mobilization. It would have four subordinate commands: an Eastern

Defense and a Western Defense Command, an Antiaircraft Command, and the

"Army University," a school command including all training

schools, Reserve training, ROTC, and the U.S. Military Academy. A

Development Command would be responsible for both research and

development and for combat development functions, including operations

research, war gaming, and human resources research. A Service Command

would include most of the

[219]

THE BENDETSEN PLAN, 22 OCTOBER 1952

DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY STAFF

Source: OCM Files.

[220]

Quartermaster Corps functions,

Army hospitals, finance centers, transportation, maintenance facilities,

and surplus disposal facilities. A Procurement Command would combine the

procurement and production functions of the Ordnance Department with

the construction activities, both military and civilian, of the Corps of

Engineers. It would be, like them, organized geographically into

regional divisions or districts.

Bendetsen thought there might be

a continued need for a separate Army headquarters command like the

Military District of Washington. Turning to the organization of the

General Staff and the Department of the Army, Bendetsen criticized the

Pershing tradition of attempting to run the department as if it were a

field command. The organization of a field army, he said, was

inappropriate for the department because the latter's mission was not to

direct military operations but to supply materiél and trained manpower

for such operations. He would relieve the General Staff of all

operational responsibilities, leaving five staff divisions: Manpower,

Intelligence, Operations, which he would separate from Force

Development (Training), and Procurement, Supply, and Services. The

technical

services would become staff agencies with no field commands or

installations under them. At the special staff level he would assign

Military History and Troop Information to the Adjutant General's Office.

There would be a vice chief and

two deputy chiefs, Bendetsen went on, to assist the Chief of Staff, one

for Plans and Research who would link long-range strategic planning with

research and development and a deputy for Operations and Administration.

Like others, he insisted that combining plans and operations in one

agency did not make sense. He would also appoint special assistants for

political-military affairs and for Reserve Components.

The Secretary of the Army would

have three assistant secretaries, one for Personnel, another for

Procurement, Supply, and Services, and a third, the Comptroller, because

the latter should parallel the role of the Comptroller of the Department

of Defense who was a civilian.3

While nothing

came of Mr. Bendetsen's plan at the time, it

[221]

was representative of the

continuing criticism of the Army's organization and management outside

the department. Some of its criticisms and recommendations were also

reflected in the reports of various committees that were appointed by or

under General Eisenhower when he became President in 1953.

President Eisenhower appointed

Charles E. Wilson as Secretary of Defense. One of Wilson's first acts

was to designate Nelson A. Rockefeller on 19 February 1953 as chairman

of an ad hoc committee on the organization of the Department of

Defense. It was a blue-ribbon jury, consisting of General of the Army

Omar N. Bradley, chairman of the joint Chiefs of Staff, and Dr. Vannevar

Bush, both of whom had publicly criticized the national defense

organization; Dr. Milton Eisenhower; former Secretary of Defense Robert

A. Lovett; Arthur S. Flemming, Director of the Office of Defense

Mobilization; and Brig. Gen. David A. Sarnoff, U.S. Army Reserve, of

RCA. Other senior military consultants were General of the Army George

C. Marshall, Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, and General Carl Spaatz,

U.S. Air Force.

The Rockefeller Committee

examined the entire spectrum of defense organization and procedures. It

sought a Department of Defense so organized and managed that it could

"provide the Nation with maximum security at minimum cost and

without danger to our free institutions." This required a flexible

military establishment "suitable not only for the present period of

localized war, but also in time of transition to either full war or

relatively secure peace."

The committee severely

criticized the various boards created under the National Security Act of

1947 which had been hamstrung, as Mr. Lovett pointed out, by

interservice rivalry. It recommended replacing them with seven Assistant

Secretaries of Defense with power to act for the Secretary. For the

Research and Development Board, the committee recommended one

Assistant Secretary for Research and Development and another for

"Applications Engineering," who would act in the area of

development engineering, thus linking research and production. To

replace the Munitions Board it recommended an Assistant Secretary for

Supply and Logistics. Other assistant secretaries would be responsible

for Properties and Installations, for Legislative Affairs, and for

Health and Medi-

[222]

cal Services. It also

recommended adding a General Counsel for the department.4

President Eisenhower accepted

many of the recommendations of the Rockefeller Committee in forwarding

his Reorganization Plan No. 6 of 1953 to Congress. The new

organization strengthened the authority of the chairman of the joint

Chiefs of Staff over his colleagues and over the joint staff. Following

the Rockefeller Committee's recommendations Reorganization Plan No. 6

abolished the several defense boards, assigning their functions to the

Secretary of Defense, and provided him with six new assistant

secretaries and a General Counsels.5

Finally it made the service

secretaries "executive agents" for carrying out decisions of

the JCS. The chain of command now ran from the JCS through service

secretaries to the various overseas commands.

The three service secretaries,

at Secretary Wilson's request, were also studying ways of improving the

effectiveness of their own organizations. The new Secretary of the Army,

Robert T. Stevens, on 18 September 1953 appointed an Advisory Committee

on Army Organization which looked like a gathering of Ordnance alumni.

The chairman was Paul L. Davies, vice president of the Food Machinery

and Chemical Corporation and a director of the American Ordnance

Association. Other members were Harold Boeschenstein, president of OwensCorning

Fiberglas; C. Jared Ingersoll, director of the Philadelphia Ordnance

District during World War II and president of the Midland Valley

Railroad; Irving A. Duffy, a retired Army colonel who was a vice

president of the Ford Motor Company; and Lt. Gen. Lyman L. Lemnitzer,

Deputy Chief of Staff for Plans and Research.

Secretary Stevens had requested

the committee to consider all elements of the Army, field commands as

well as the departmental organization in Washington. Areas of

particular interest

[223]

were the organization of the

Army's top management in the light of President Eisenhower's

Reorganization Plan No. 6; the organizational changes required to carry

out the Secretary's new assignment as the JCS's executive agent for

certain overseas commands; organizational changes necessary in

supervising and co-ordinating the technical services effectively;

changes required for proper direction of the Army's research and

development

program; the proper locations within the department of its legal and

legislative liaison functions; and, finally, the organization and

functions of the Office, Chief of Army Field Forces.6

The committee hired McKinsey and

Company, a Chicago management consulting firm, as its full-time civilian

staff with John J. Corson as its head, and interviewed 129 witnesses

over a three-month period, including the heads of every major

organizational unit in the Army. The committee submitted its report to

Secretary Stevens on 18 December 1953.

The committee proposed four

major changes in the organization of the Army. Among other things it

would strengthen the Secretary's fiscal control by adding an Assistant

Secretary for Financial Management and increase the authority of the

newly appointed Chief of Research and Development-within the Office of

the Deputy Chief of Staff for Plans and Research by transferring

responsibility for research planning to his office from the Assistant

Chief of Staff, G-4. The most important recommendation would remove the

Army staff entirely from "operations" by creating two new

field commands, a Continental Army Command which would be responsible

for supervising Army training instead of G-3, and a Supply Command

which would relieve the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-4, of the

responsibility for "directing and controlling" the technical

services.7

The Davies Committee recommended

that the Secretary of the Army "participate actively in the

formulation" of basic national policies and strategies affecting

the Army by, among other things, attending National Security Council

meetings as

[224]

an "observer." The

Under Secretary would be replaced by a deputy secretary who would act

for the Secretary in administering the department. Adding a third

assistant secretary would permit each to specialize in one functional

area, that is, manpower, materiél, and financial management.

The Chief of Staff, the

committee asserted, should be the "operating manager" of the

Army. "The view is often expressed in the Army that the Chief of

Staff commands no one and is merely chief of the Secretary's staff. In

practice this is not the case. He is the operating manager of the Army

Establishment . . . ." It recognized his role as a member of the

joint Chiefs of Staff and suggested reducing the number of agencies

reporting directly to him.8

Other organizational changes

proposed were to strengthen the Army's Reserve program; to place the

Secretary's Office of Civilian Personnel under the control of the Chief

of Staff because he was ultimately responsible for the work done by Army

civilians; to place greater emphasis on Civil Affairs and Military

Government; and to make the judge Advocate General the responsible

legal adviser in the department with supervision over all legal staffs

throughout the Army.9

The committee rejected the

concept of a separate Operations Division such as proposed by Mr.

Bendetsen because, it said, strategic planning was now largely a

function of the joint staff and much of the responsibility for training

would now be delegated to a new Continental Army Command. It also

rejected

the idea of a separate "intelligence corps" because this would

create additional operating responsibilities for G-2. It recommended

that the Corps of Engineers retain its civil works functions rather than

'transferring them to another department of the government.10

The committee's proposal for a

training command was a return to the wartime concept of Army Ground

Forces. The Continental Army Command, operating under the supervision of

G-3, would be responsible for all "combat arms" training in

the Army, individual as well as unit, basic and combined, Regular and

Reserve.

A training command was necessary,

the Davies Committee

[225]

said, because the six

continental armies and MDW were attempting to serve too many masters.

The General Staff divisions each supervised a part of their activities.

Under a single Continental Army Command there would be snore effective

control and direction over their activities.11

The Davies Committee proposals

concerning the Army's supply system represented a partial return to the

concept of General Somervell's wartime ASF. Its members suggested three

major changes in this area: creation of a Vice Chief of Staff for

Supply; creation of a Supply Command; and elimination of the division of

responsibility between the ZI armies and the technical services for

operating Class II installations. A Vice Chief of Staff for Supply and

another for Operations were necessary, it said, because direction of the

Army's supply system required the full-time services of "a highly

experienced and qualified individual" familiar with all aspects of

supply management and planning.12

A Supply Command was necessary

for the effective control over the technical services. Under the

existing organization G-4, although responsible for directing and

controlling the activities of the technical services, shared authority

over them with other staff divisions, principally the Army Comptroller

and G-1. A Supply Command would have greater control over the technical

services in these areas and over training, while G-4 would remain

responsible for logistical planning and policies.

The committee did not think it

would be necessary or desirable to reorganize the technical services

along "functional" lines. "The controlling

consideration," it said, "is whether the advantages of greater

specialization, coordination, and uniformity with respect to a function

. . . are more important than the need for coordinating and

resolving all differences among functions with respect to an item . . .

. Coordination of the development, procurement and distribution of an

item is a more meaningful basis for organization . . . than

specialization in each function." This view accorded with that of

the Ordnance Department.13

For research

and development as mentioned above the

[226]

Davies Committee proposed to

strengthen the existing authority of the Chief of Research and

Development in the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Plans and

Research by transferring to his office the planning functions in this

area then assigned to G-4. Research and development operating

responsibilities it would transfer to the Supply Command.

The existing organization of the

Army staff, it admitted, diffused responsibility for research and

development, and it acknowledged that many people felt that research,

essentially a planning function, had been subordinated to current

production

and procurement operations.

The committee, on the other

hand, believed a separate research and development division on the

General Staff or the creation of a separate "Development"

Command would cause more difficulties than it would overcome. It did not

believe that a special staff division would improve the co-ordination

and management of research and development in the Army. A separate

"functional" command would "separate research and

development from closely related procurement and distribution

activities." The Army would then have to find a new means of

integrating these "essentially integral activities." Removing

"development" from the influence of those concerned with

production and procurement would "insulate" research personnel

from the views of the user of weapons and other materiél. This, too,

was the view of the Ordnance Department.

A more effective research and

development program it believed would come from employing qualified

civilian scientists and "project managers" and from

contracting directly with civilian institutions "for special

research undertakings."14

Eliminating the existing

division of responsibility between the technical services and the

continental armies for operating Class II installations was also

necessary. Commanders of such installations were responsible to the

technical service chiefs for the performance of their missions. At the

same time they depended on the continental Army commanders for

housekeeping funds. This violated the principle of unity of command and

made it impossible to determine the costs of operating such

installations. The committee recommended that housekeeping funds and

personnel be allotted directly to the technical services

[227]

who would then have complete

financial responsibility over the operations of their field

installations.15

Another area the committee

investigated was financial management. The addition of another

assistant secretary with responsibility for such matters it hoped

would strengthen the program. But further improvement required aligning

fiscal responsibility with the department's organizational structure.

The new budget and program system had not yet produced satisfactory

results, partly because it did not conform to the Army's organization

pattern and partly because it did not extend all the way down to the

installation level.16

Like earlier civilian

reorganization proposals the Davies Committee report insisted the Army

staff should get out of operations, while military officers like those

on the PatchSimpson Board had asserted that this simply could not be

done. The proposal that met the strongest opposition within the Army;

creating a Supply Command, involved this principle. The basic military

argument against it was simply that it was impossible to divorce the

General Staff from its responsibility for supply operations. The Army

staff's reaction was to turn the Davies proposal upside down. Instead of

a Supply Command the Army staff proposed making the G-4 a Deputy Chief

of Staff for Logistics with greater "command" over the

technical services.

The principal protagonist of

this view was Lt. Gen. Williston B. Palmer, the new G-4. General

Palmer, unlike his predecessors, Generals Somervell, Lutes, and Larkin,

who were primarily logisticians, was a combat veteran. Most recently he

had served in Korea as commanding general of the X Corps. As a combat

commander General Palmer insisted on unity of command and felt that he

should have all the authority and resources needed to carry out his

command responsibilities. In his view it was necessary either "to

give G-4 substantial command over the Technical Services" or to

resurrect Army Service Forces, which would cause considerable confusion.

If the first alternative were chosen, the G-4 should be given authority

over personnel, organization, and review and analysis. While he had

[228]

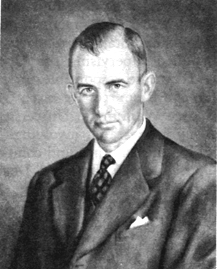

GENERAL PALMER (Photograph taken in 1955.)

no wish to interfere with the

responsibilities of his colleagues, General Palmer said, "I must

have within my own hands the management tools and the primary control

over personnel and organization questions within the logistic

area." In these arguments General Palmer reiterated General

Aurand's position in 1948 concerning greater substantive control over

the technical services.17

In briefing the new Chief of

Staff, General Matthew B. Ridgway, on 19 August 1953 General Palmer

resorted to the Constitutional doctrine of "implied powers,"

quoting Chief Justice John Marshall's decision in McCulloch versus

Maryland to support his point. His authority under Special

Regulation 10-15-1 included not only logistic staff functions but also

direction and control of the technical staffs and services. "All

the responsibility is given me, and all powers necessary to discharge

the responsibilities must be inferred as granted.

The Chiefs of Technical Services

are commanders, and their commands are huge. I would judge it to be true

that real control over them lapsed when ASF was disbanded." For

this reason he requested greater authority over personnel, including

general officers in the technical services, and over Class II

[229]

industrial installations. He

also wanted better qualified "management" personnel because

"the civilian secretaries are challenging us to show that the Army

staff is capable of running the Army supply system."18

While the Davies Committee

deliberated, there were rumors within the Army staff that creating a

Supply Command would be one of its major recommendations. A General

Staff committee requested the G-4's formal position on the Army's

"Logistic Structure at the Departmental Level." Speaking for

General Palmer, Maj. Gen. Carter B. Magruder, his deputy, said that

G-4's existing authority, based on applying the theory of implied

powers, was adequate for managing the Army's supply system.

"Creation of a Logistics Command," he said, "would

require a large headquarters and would interpose a ponderous additional

step in doing business, with no obvious improvement in management."

The experience of both world wars demonstrated that the supply

organization finally evolved combined both logistical staff planning

with command over the supply services. General Somervell himself,

General Magruder asserted, "favored an ASF commander who would

also be the Chief of Staff's advisor on logistics." The

organization of the technical services themselves was

"fundamentally sound." Simple directives could reassign

functions among them whenever necessary. What they needed was

"vigorous direction, control, and coordination by a single

authority."

General Magruder's principal

complaint was that civilian officials in the Secretary's Office and

above were becoming increasingly involved in administrative details.

"Many decisions have to pass three [sic] Army secretaries

and then go to more than one secretary in Defense." 19

General Palmer encountered

opposition from Maj. Gen. Robert N. Young, the Assistant Chief of Staff,

G-1, on control over technical service personnel. The latter said that,

according to "the General Staff concept," G-4 should not

exercise authority over personnel. General Palmer's spirited rebuttal

was that every effort on his part to obtain authority matching his

[230]

responsibility met objections based on the "General Staff concept."

". . . Experience since 1917 in three [sic] national

emergencies shows that we always come to the same solution, of

placing on one man the dual function of principal logistic adviser

and logistic commander. That is where the facts of life push us

every time. The General Staff concept needs to be rewritten if it

doesn't conform."20

He objected on the same basis to a

statement by another colleague that "The Assistant Chiefs of

Staff do not command, and it is not consistent with Army doctrine to

show the administrative services under G-1 and the Technical

services under G-4." 21

General Palmer's reaction to the Davies Committee report was

mixed. He seemed to accept the general outlines of the report in

principle, including a Vice Chief of Staff for Supply, because he

thought it would improve the conduct of the Army's "business

affairs." But he firmly objected to interposing a Supply

Command between the technical services and the Chief of Staff.

"The Chiefs of the Technical Services must remain at as high an

echelon as now. In a thousand cases a day, they must be spokesmen

for the Department. Displacement from their departmental functions

would hopelessly snarl Congressional, executive, and inter-service

relations, and could only end in creating a whole new set of

technical staffs which would, inevitably, include the Chiefs of

Services personally." As an alternative he proposed placing a

"Director of Logistics Services" directly under the Vice

Chief of Staff for Supply and so avoid "futile argument"

over creating a field "Command" within the department.22

General Palmer continued his argument with General Young over

personnel functions. General Young proposed removing responsibility

for career management from the technical services and placing it

along with responsibility for career management for combat arms

officers in G-1. General Palmer and the chiefs of the technical

services all strongly disagreed with this proposal. Among other

things it was contrary to the Davies Committee's recommendation that

responsibility for

[231]

- technical service career

management be placed under the new Supply Command.23

-

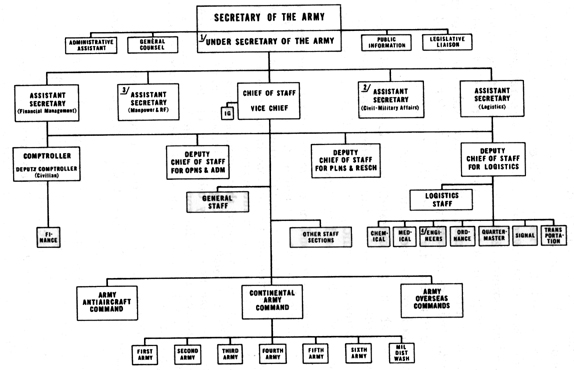

- The Department of the Army

publicly announced "the Secretary of the Army's Plan for Army

Organization," known as "the Slezak Plan" after the new

Under Secretary of the Army, John Slezak, on 14 June 1954, and the

Secretary of Defense approved it on 17 June 1954. In general the plan

followed the recommendations of the Davies report except in the field of

logistics. There it reflected the views of General Palmer in rejecting

the concept of a Supply Command and giving a new Deputy Chief of Staff

for Logistics "command" over the technical services.24

(Chart 20)

-

- The plan agreed with the Davies

Committee that G-4 lacked the authority needed to control and direct the

technical services. "The major weaknesses in the Army's structure

and operations," it said, "do not lie in the field of military

operations, but are traceable to a lack of recognition of, and

preparation

for, changes in the character, size, and complexity of the Army

Establishment necessary to produce and support the combat forces."

But the Slezak plan in disagreeing with the Davies Committee's remedy

said:

-

- If an integrated Army logistics

system is to be achieved, the appointment of a Deputy Chief of Staff

for Logistics is a vital first step. The Deputy Chief of Staff for

Logistics must be given full authority for the provision,

administration, and control of military personnel, civilian personnel,

and funds for, and the direction and control of, the seven Technical

Services.

-

- He "should have a command

relationship to the Technical Services" and exercise staff

supervision over "wholesale-level logistics activities

overseas."

-

- The Army should first transfer

from other Army staff agencies to the Deputy Chief of Staff for

Logistics all functions involving the technical services,

"including, but not limited to, career management, personnel

administration, and manpower control; budgeting, apportionment, and

allocation, of all funds among the Technical Services, and other

financial management functions and activities; materiél research and

development;

- [232]

- SECRETARY OF THE ARMY'S (THE SLEZAK) PLAN, 14 JUNE 1954

-

-

- 1 General Management, Analysis and Review

- 2 Panama, Alaska, Civil Functions, Politico-Military- Economic

Affairs

- 3 Direct working relationships with civilian and military personnel

elements of Army staff

- 4 Additional direct responsibilities to Assistant Secretary (Civil

Military Affairs)

-

- Source: Secretary of the Army's (the Slezak) Plan, 14 June 1954.

- [233]

- requirements, procurement,

supply, services, and programing and control functions in the logistics

field; and legal functions of the Technical Services." It would

also transfer responsibility for technical service training to the new

deputy chief. For the time being at least responsibility for logistics

planning would remain with a vestigial Assistant Chief of Staff, G-4.

The General Staff was thus removed from logistics operations entirely.25

-

- An ad hoc Committee to Implement

the Reorganization of the Army composed of the Comptroller, the G-4, and

other General Staff divisions under the chairmanship of George H.

Roderick, Assistant Secretary of the Army for Financial Management,

met repeatedly during the summer of 1954 to work out the details of the

reorganization.26

-

- Mr. Slezak, in a memorandum for

General Ridgway on 8 September 1954 approving the detailed

reorganization plan, called his attention principally to the Charter for

the new Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics.

-

- a. The purpose is to combine the

seven technical services into an integrated logistical system,

subordinating the Chiefs of Technical Services to the head of this

system and giving him authority to modify the respective Technical

Service missions in order to achieve one integrated system in place of

seven autonomies.

-

- b. Accordingly, it is intended

that wherever the authority granted the Deputy Chief of Staff for

Logistics involves transfer to him of authority heretofore exercised by

other parts of the Army staff, the extent of the transfer shall be

interpreted so as to insure that the Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics

can carry out the objectives set forth in paragraph a. above.

-

- Specifically this meant that he

would have authority over "the career management of all Technical

Service personnel, whether serving under their Chiefs or not." 27

-

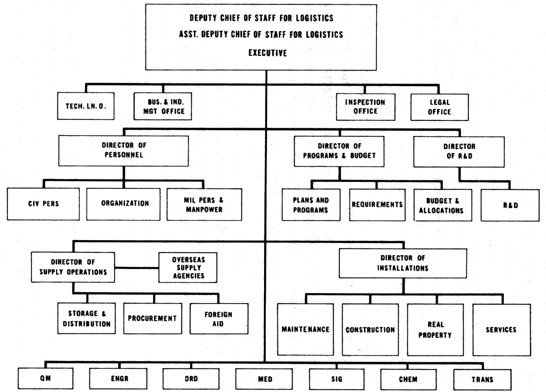

- The Charter to which Mr. Slezak

referred was published as Change 4 to Special Regulation 10-5-1 of 8

September 1954. As revised-later in Change 6 of 17 January 1955, the

Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics had "Department of the Army

Staff responsibility" for "development and supervision of an

integrated Army logistics organization and system, including all

controls over policies, procedures, standards, funds, manpower,

- [234]

- and personnel which are

essential to the discharge of this responsibility." He would be

responsible for the development of logistics doctrine and manuals, for

supervising logistics training and education where more than a single

technical service was involved, for logistics planning, for development

of logistics programs and budgets, for development and supervision

of financial management, including stock and industrial funds within the

technical services, and for development of the Army's logistics

requirements. Acting on the basis of this authority he was to prescribe

the missions, organization, and procedures of the technical services, to

supervise their training, develop and supervise "a single,

integrated career system" for technical service personnel, to

exercise manpower controls over both their civilian and military

personnel, to administer their civilian personnel programs, including

industrial and labor relations, and to supervise all aspects of

financial management within the technical services, including budgets,

funding, allocation of personnel ceilings, review and analysis, and

statistical reporting controls under the authority of the Comptroller

of the Army. The Surgeon General was allowed direct access to the

Secretary and the Chief of Staff on matters involving the health and

medical care of troops and utilization of medically trained military

personnel. Responsibility for the civil functions of the Chief of

Engineers was not included. Change 6 also removed from the Deputy Chief

of Staff for Logistics responsibility for directing the research and

development activities of the technical services. The organization of

the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics to carry out these

new duties is outlined in Chart 21.

-

- The Secretary of the Army

reappointed McKinsey and Company on 8 February 1955 to conduct an

"Evaluation of Organizational Responsibilities" within the

Department of the Army. This review concentrated on the Army's civilian

secretariat, the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics,

and the new Continental Army Command.28

-

- The only major recommendation made

concerning the Sec-

- [235]

- OFFICE OF THE DEPUTY CHIEF OF STAFF FOR LOGISTICS, 9 SEPTEMBER 1954

-

-

- Source SR 10-5-1 Change 4,8 Sep 54, and Internal Deplog Organization

Chart of 9 Sep 54.

- [236]

- retary's Office was that an

Office of Director of Research and Development be created separate from

the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Logistics and Research and

Development. This change was adopted and announced in General Order 64

of 3 November 1955. The remainder of McKinsey and Company's comments in

this area concerned redistributing the work load among the various

assistant secretaries and preventing them from becoming involved in

minor administrative operations.29

-

- McKinsey and Company thought

that the responsibilities of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics

under Changes 4 and 6 to Special Regulation 10-5-1 were not clear,

particularly in the areas of overseas supply activities, doctrine,

training, and logistics planning. The report warned that this office

might become so involved in operations that it could not give sufficient

attention to logistics planning which might better be assigned to a new

G-4 division. Greater responsibility for operations ought to be given to

the chiefs of the technical services as "operating Vice

Presidents." The Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics should instead

concentrate his efforts on developing policies and programs common to

more than one technical service and follow the principle of

"management by exception," or troubleshooting, in dealing

only with critical problems. He should limit reports to those providing

information needed to develop and review policies and programs. Other

minor suggestions concerned personnel management, program review and

analysis, and financial management. 30

-

- The Comptroller of the Army

asked Karl R. Bendetsen, then a Reserve colonel on active duty, to

prepare a special study on "A Plan for Army Organization in Peace

and War," which he submitted on 1 June 1955. While he repeated the

recommendations he had made to Secretary Lovett in 1952 for a series of

functional field commands, he also reviewed recent developments in

departmental organization. He thought the only real advantage of the new

Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics was his increased authority over

career management in the technical services. He still was not a

"commander," no

- [237]

- matter how that term was

defined, but a General Staff officer acting for the Secretary of the

Army.

-

- Mr. Bendetsen thought the Army

had been following a "circular course" since World War II of

first rejecting the idea of ASF and then working back toward it

gradually. There were still seven independent technical services.

General Somervell had tried hard to get rid of them, but he had failed.

Since then the deficiencies which General Somervell had tried to correct

had repeatedly come to the department's attention. It had tried to solve

them, but so far without success. The one major weakness, the

independence of the technical services with their duplication of each

other's functions, had not been rectified. "Every proposal which

has advanced the concept of bringing like functions under effective

management has met the same fate-it has been rejected." So far as

the new organization of the Army's supply system was concerned, he saw

no reason why it should succeed where its predecessors had failed, since

it did not deal effectively with this critical issue.31

-

- The new organization had other

critics besides Mr. Bendetsen. Civilian scientists had repeatedly

complained about the continued subordination of research and development

to procurement and production. When General Williston B. Palmer had

been promoted to Vice Chief of Staff, he warned that research and

development needed "rank and prestige which would place the Army on

equal terms with the other services before the innumerable outside

scientists and advisory groups get into the act." The result was

Change 11 to Special Regulation 10-5-1 of 22 September 1955 creating

the Office of Chief of Research and Development at the Deputy Chief of

Staff level. The designation chief was necessary because Congress had

specifically limited the Army to three Deputy Chiefs of Staff in the

Army Organization Act of 1950.32

-

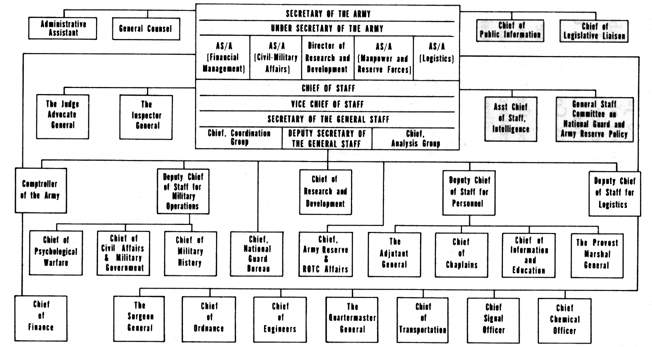

- This organization left a General

Staff of five Deputy Chiefs of Staff co-ordinating operations with three

Assistant Chiefs of Staff below them, presumably divorced from

operations. General Palmer's view was that "The General

Staff has always

- [238]

- operated." If it was

responsible only for plans and policies, "what agency would

supervise their execution?" On this basis the Army staff was

reorganized as of 3 January 1956 under Change 13 to Special Regulation

10-5-1 of 27 December 1955 into three Deputy Chiefs of Staff, one for

Personnel, another for Military Operations, and the third for Logistics,

a Chief of Research and Development, the Army Comptroller, and an

Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence. (Chart 22) The Deputy Chief

of Staff for Personnel absorbed the functions of the former Deputy Chief

of Staff for Operations and Administration plus G-1. He was also

assigned direct supervision and control over The Adjutant General's

Office, the Chief of Chaplains, the Provost Marshal General, and the

Chief of Information and Education. The Deputy Chief of Staff for

Military Operations absorbed the functions of the former Deputy Chief of

Staff for Plans plus G-3. He was also assigned General Staff supervision

and control over the Chief of Civil Affairs and Military Government, the

Chief of Psychological Warfare, and the Chief of Military History.33

-

- Thus was abandoned the

three-deputy concept for coordinating and supervising the operations

of the Army staff. The Deputy Chiefs of Staff for Plans (Research) and

for Operations and Administration as well as the Comptroller, which

had performed these functions since 1949, were now demoted to the status

of coequal General Staff agencies. To fill the vacuum left at the top

the Chief of Staff created two new agencies within the secretariat of

the General Staff, a Coordinating Group and a Programs and Analysis

Group (initially called the Progress Analysis Group). The secretariat

thus began to develop into a super co-ordinating and planning staff

between the General Staff and the Chief of Staff. 34

-

- The Coordination Group's formal

mission was to assist the Chief of Staff in the development and

evaluation of long-range strategic plans. It acted as liaison also with

other Army and defense committees, including the joint Chiefs. In

practice

- [239]

- DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY CHIEFS AND EXECUTIVES, 3 JANUARY 1956

-

-

- 1 Not an Official Organization Chart.

- 2 For Practical Purposes Those Agencies Listed as Technically

Subordinate to DCSOPS, DCSPER, and DCSLOG, Actually Reported Direct to

the Chief of Staff. Source: DA, DO No 70, 27 Dec 1955. CSR 10-1, 3 Jan

56.

-

- Prepared by TAGO

- [240]

- this meant the Coordination

Group assisted General Maxwell D. Taylor, the new Chief of Staff, in

developing an integrated Army philosophy which would serve to

revitalize the Army's missions and roles. Some such conscious, explicit

philosophy, General Taylor believed, was necessary, spelling out the

role of the Army in the national defense establishment, if the Army were

to obtain the support of the administration, Congress, and the public.

General Taylor first presented his ideas in "A National Military

Program" to the JCS in the fall of 1956. The Coordination Group,

meanwhile, prepared a Department of the Army Pamphlet, A Guide to Army

Philosophy, which was widely distributed within the Army in 1958.

Later in The Uncertain Trumpet General Taylor published the

substance of this program, which became the basis of the Army's program

in the 1960s. 35

-

- Co-ordinating the Army's program

system was the responsibility of the new Programs and Analysis Group.

This meant the proper balancing of Army programs with resources in men, materiél, and money. The planning, execution, and review and analysis of

the Army's programs at the Army staff level were now under one small

agency in the Chief of Staff's Office.

-

- Under the new dispensation the

Management Office within the secretariat became, in effect, the

Comptroller of the Army staff but the relationship between this agency

and the Office of the Comptroller of the Army was not clear. In theory

the Management Office's responsibilities for management functions

within the Army staff included the Comptroller's Office, while the

Comptroller of the Army was responsible for such functions throughout

the Army. Theoretically the Comptroller's Office would review the Army

staff's budget and manpower ceilings, including those of its own

headquarters, prepared by the Management Office. In practice, the

Comptroller had been reduced to the level of a Deputy Chief of Staff

coequal

with but not superior to his colleagues as he had been before 1956.

-

- No major change took place in

the organization of the Army staff or the Chief of Staff's Office from

1956 until John F.

- [241]

- Kennedy became President and

appointed Robert S. McNamara as Secretary of Defense in January 1961.

The size of the Army staff and of the secretariat both remained fairly

constant during this period. 36

-

-

- The emergence of the Office of

Chief of Research and Development on 10 October 1955 as an independent

General Staff agency ended a strenuous five-year campaign for

recognition by civilian scientists both within and outside the Army. It

was also part of the continuing struggle for control over the technical

services because they performed most of the research and development

within the Army.37

-

- Under the Eisenhower

reorganization of 1946 recognition of research and development within

the Army as an activity separate from logistics seemed assured with the

creation of a separate Directorate for Research and Development. The War

Department Equipment Board, known as the Stilwell Board, in its report

of 29 May 1946 reiterated General Eisenhower's statement of Army policy

on research and development.

-

- Scientific research is a paramount

factor in National Defense. It is mandatory that some

procedure be adopted whereby scientific research is accorded a major

role in the post war development of military equipment. The scientific

talent available within the military establishment is not adequate for

this task and must be augmented . . . . In general the scientific

laboratories of the Technical Services should be devoted to those

problems so peculiarly military as to have no counterpart among

civilian research facilities, meanwhile utilizing, on a contract basis

the civilian educational institutions and industrial laboratories for

the solution of problems within their scope.

-

- The board recommended a separate

Directorate of Research and Development as the best means for

supervising the program. The director should be a senior general officer

of the Army, it said, and key personnel should include knowledgeable

- [242]

- officers from each technical

service, a nationally known scientist as senior assistant to the

director, and an outstanding scientist in each major field of science

assigned on rotation from the major scientific colleges and industrial

laboratories. General officers from the field commands and officers from

each arm and service should represent the using arms in the development

of new or improved weapons.

-

- The mission of the Directorate

of Research and Development was to supervise all Army research

activities and to coordinate the research and development activities

of the arms and services. It would establish priorities, make certain

that the technical services and arms maintained contact with civilian

research programs, supervise and review the Army's long-range research

and development program, confirm the need for new and improved

equipment, and advise the Budget Division on the funds required for its

work.

-

- To increase the Army's

scientific talent, the Stilwell Board report recommended commissioning

outstanding civilian scientists in the Army Reserve or National Guard,

sending Army officers as students to leading scientific colleges and

industrial laboratories, granting commissions annually to graduates of

scientific colleges, and providing salaries that would attract qualified

civilian scientists to work for the Army.38

-

- The department neglected most of

the Stilwell Board's recommendations because of reduced budgets

following World War II. Dr. Cloyd H. Marvin, the first "Scientific

Director," complained in late 1947 that the Army lacked a vigorous,

modern research and development program. He recommended a reorganization

with an Assistant Secretary of the Army for Research and Development and

conversion of the General Staff to a purely planning agency supporting

functionally organized field commands. One of the commands would

consolidate the Army's research laboratories, and another would

determine the development of tactical doctrine and military requirements

for new material. It would be responsible for testing new weapons and

equipment and for operating the Army's advanced schools. For an

effective program the Army

- [243]

- ought also to have a separate

research and development budget.39

-

- Abolishing the Research and

Development Directorate and subordinating the function to Logistics in

December 1947 was a step backwards. Severe budget limitations, a factor

beyond the Army's control, forced the Army to get along with surplus

weapons and equipment left over from World War II. New weapons, except

for missiles, were out of the question. General Aurand, the first

Director of Research and Development, also complained he had found it

extremely difficult to obtain agreement from the Logistics Directorate

on research and development projects.40

-

- None of the reorganization

studies of the Army by the Management Division, Cresap, McCormick and

Paget, and the Hoover Commission Defense Task Force dealt with research

and development. In recommending a functional Army staff and functional

field commands, their proposals contained no provisions for research and

development as a separate activity at any level. The only important

advance in this otherwise sterile period for Army research and

development was the signing of a contract with the Johns Hopkins

University in July 1948 setting up a General Research Office, later

known as the Operations Research Office (ORO), to perform research for

the Army. As the title indicated, ORO's principal activities were

limited to employing scientific methods, specifically operations

research techniques, in improving current tactical doctrine rather than

developing new weapons or equipment.41

-

- Distinguished civilian

scientists like Dr. Vannevar Bush complained about the way the services

were handling research. A major irritant was the relationship between

scientists and their military superiors in the development of new

weapons. Writing in 1949 Dr. Bush, the first chairman of the Research

and Development Board, asserted:

-

- The days are gone when military

men could sit on a pedestal, receive the advice of professional groups

in neighboring fields who were maintained in a subordinate or tributary

position, accept or reject

- [244]

- such advice at will, discount

its importance as they saw fit, and speak with omniscience on the

overall conduct of war . . . . If military men attempt to absorb or

dominate the outstanding exponents in these fields, they will simply be

left with second-raters and the mediocre . . . . The professional men

of the country will work cordially and seriously in professional

partnership with the military; they will not become subservient to them;

and the military can not do their full present job without them.42

-

- As a member of the Army Policy

Council, Dr. Bush also expressed his dissatisfaction with the progress

of the Army's research program to Secretary of the Army Gordon Gray in

the spring of 1950. Gray in turn sent a memorandum to the Chief of Staff

complaining that the Army was placing too much emphasis and spending too

many dollars on maintaining its current arsenal at the expense of the

future. Given the pace of scientific advance, the next war was not

likely to be the same kind of "total war" as World War II.43

-

- Secretary Gray's memorandum led

to a formal staff study of the entire Army research and development

organization. The Kilgo report, so designated because Mr. Marvin M.

Kilgo of the Comptroller's Office reportedly collected most of the

information, was sent to the Secretary on 12 January 1951. In substance

it argued that the Army's research and development program lacked

effective leadership from the Defense Department and inside the Army.

It recommended a separate Assistant Chief of Staff for Research and

Development with control over funds for such activities and a Deputy

Chief of Staff for Development. There should be a direct link, it said,

between these programs and the Army's strategic planning, and greater

use should be made of "operations research" techniques by

setting up organizations for this purpose in all major commands.44

-

- General Larkin, the G-4, spoke

for the Army staff in rejecting the major proposals of the Kilgo

report. He and all the technical service chiefs were opposed to a

separate Research and Development Division on the General Staff. It had

been tried and found wanting, they said. The Army could perform this

mission just as well under the supervision of G-4, and it was

- [245]

- important to retain the link

between research and procurement. Besides, the technical services

ought to report through only one direct command channel.

-

- The Chief of Staff, General

Collins, repeated General Larkin's comments in his recommendations to

the new Secretary of the Army, Frank Pace, Jr. Staff responsibility

for research and development should remain, he said, with G-4. It was

also essential to integrate this program with production because at the

technical service level they were combined. Further, he did not see

how "pure" research could be separated from development.45

-

- Secretary Pace accepted these

recommendations but left the issue of a separate Research and

Development Division open. Some Army staff officials believed that the

main current problem was the lack of firm strategic planning on which

to base projections of future research and development requirements. The

Chief of Research and Development in G-4 believed a change was desirable

in the technical services, which would make the head of research and

development in each service responsible directly rather than indirectly

to the chief of the service. Civilian personnel shortages were also

hindering progress.46

-

- In the fall of 1951 Maj. Gen.

Maxwell D. Taylor, then Deputy Chief of Staff for Organization and

Training, sought to reopen the question of a separate Research and

Development Division because "its increased importance and extended

scope make increasingly, apparent the lack of logic in assigning

Research

and Development to G-4." Secretary Pace agreed that "the

departmental research and development functions must be removed from

G-4." By this time opinion within the General Staff had shifted.

Most favored a separate General Staff division in some form, but the G-2

and G-3 suggested placing this function under the Deputy Chief of Staff

for Plans. General Larkin and General Collins still opposed a separate

staff agency.

-

- At this point General Taylor

canvassed senior officers of the Army including the chiefs of the

technical services on the subject. The G-1, Lt. Gen. Anthony C.

McAuliffe, strongly

- [246]

- SECRETARY PACE

-

- urged removing the function from

G-4. Placing it under the Deputy Chief of Staff for Plans with

additional research and development elements in each major staff agency

he thought "a screwy idea" that would further fragment

responsibility for the program. General Taylor himself favored such a

plan because he thought it would force all General Staff agencies to

focus attention on the subject. No one at this time proposed changes at

the technical service level where the greater part of the Army's

research and development work was done. 47

-

- After considerable debate the

Army staff reached a compromise acceptable to Secretary Pace. As a

result, on 15 January 1952 the Deputy Chief of Staff for Plans became

the Deputy Chief of Staff for Plans and Research. He was responsible for

co-ordinating the Army's research and development activities with JCS

assigned missions, war plans, and with the latest tactical doctrines. A

Chief of Research and Development under him was directly responsible for

supervising this activity as Program Director for Army Primary Program

7, "Research and Development," including responsibility for

allocating its appropriations within the Army. He would also be the

Army's spokesman on such matters in dealing with the Office of the

Secretary of Defense and other government agencies.48

- [247]

- Severe personnel limitations

forced the new Chief of Research and Development to delegate much of

his authority to the General Staff, particularly G-4. G-3's new

responsibilities included supervising the Operations Research Office,

while G-1 became responsible for supervising the activities of the Human

Resources Research Office (HumRRO) established at George Washington

University in 1951 under contract to the Army for research involving

"human factors," the individual soldier, his training, and

combat environment. What remained of the old Research and Development

Division in G-4 was responsible for supervising these activities in the

technical services.49

-

- Secretary Pace thought the

"new organization had elevated the research and development

function from its former position subordinate to the logistics function

in the Army," and there the matter rested until the Army staff

reorganization proposals of 1954.50

-

- Civilian scientists continued

their efforts to separate research and development completely from

logistics at the General Staff level. In November 1951 Secretary Pace

appointed twelve "outstanding scientists and industrialists"

as members of an "Army Scientific Advisory Panel" to assist

him and the Chief of Staff in creating a fighting force "as

effective, economical, and progressive, as our scientific,

technological, and industrial resources permit." Dr. James Killian

was the first chairman of this group and a leader in the effort to

remove research and development from G-4.51

-

- Scientists now had more direct

influence within the Army itself as part of the establishment. They

played a direct role also in the Korean War when representatives of ORO

went there to apply operations research techniques. These scientists

returned

certain that "something had to be done to improve our capability to

conduct land warfare." 52

Out of this developed

- [248]

- Project VISTA, conducted by the

California Institute of Technology under the joint auspices of the

Army, Navy, and Air Force and designed "to bring the battle back to

the battle field." One major recommendation was to create a Combat

Developments Center for testing new tactical concepts on troops in the

field. The Combat Developments Group set up in 1952 under Army Field

Forces was a direct consequence of this recommendation.53

-

- President Eisenhower's

Reorganization Plan No. 6 of 1953 reopened the question of the

relationship of research and development to logistics within the Army.

The new Defense Department organization had strengthened control over

research

and development by replacing the unwieldy Research and Development Board

with two assistant secretaries, one for Research and Development and

another for Applications Engineering, both separate from the Assistant

Secretary for Supply and Logistics. The Davies Committee on Army

organization considered separation of research from supply in its own

deliberations.

-

- General Palmer, the new G-4,

opposed any change, asserting the main issue was control over the

technical services. Another General Staff division for research and

development to whom the technical services would have to report would

make matters worse.54

-

- Dr. Killian told the Davies

Committee he was unhappy with the Army's research program. There was

still little coordination between strategic planning and research and

development. He had welcomed the appointment of Maj. Gen. Kenneth D.

Nichols as the Chief of Research and Development, but the latter's

emergency assignment to the Army's guided missiles program obviously

interfered with his main job. Dr. Killian still wanted a separate

General Staff division for research and development with direct access

to the Chief of Staff and the Secretary of the Army together with a

separate Assistant Secretary for Research and Development. He did not

think creation of a separate research and development command, such as

Mr. Bendetsen had suggested, would be practical because of

- [249]

- the necessarily close relationship between the

researcher and "the user" who developed and produced the

finished product.55

-

- The recommendations of the

Davies Committee regarding the Army's research program were a

compromise. While the committee did not advocate removing this function

entirely from G-4, it suggested transferring research and development

planning from G-4 to the Chief of Research and Development. Operating

functions should be transferred from G-4 to the new Supply Command. In

the Secretary's Office it recommended transferring responsibility for

this program from the Under Secretary to the Assistant Secretary for Materiél. It also recommended making the Army Scientific Advisory Panel

permanent 56

-

- The final Slezak plan on Army

organization irritated Dr. Killian. Writing to Secretary Stevens he

complained that the proposed organization "would serve seriously to

handicap the management and further development of the Army in Research

and Development activities . . . ." It had two serious defects.

"It brings Research and Development under the domination of

logistics and procurement philosophy, and this has repeatedly been

demonstrated to be the wrong environment for the top direction of

research in military services." Second, it actually reduced the

status of the Chief of Research and Development by making his role

ambiguous.57

General Lemnitzer, the Deputy Chief of Staff for Plans

and Research, endorsed Dr. Killian's views. Stressing the

incompatibility of research and logistics, he wrote George H. Roderick,

chairman of the ad hoc Committee for Implementation of the

Reorganization of the Army, that the only solution was to consolidate

under the Chief of Research and Development all of the existing G-4

research and development work as well as those portions of the program

scattered among other General Staff agencies.58

Maj. Gen. John F.

Uncles, Chief of the Research and Development Division, wrote Lemnitzer,

his superior, that "we are paying too high a price for rigid

adherence to the prin-

- [250]

- ciple that only a Deputy Chief

of Staff for Logistics can issue instruction to the Technical

Services." He favored centralizing all Army staff research and

development functions under General Lemnitzer's office rather than the

"present dispersed and inadequate staff organization." 59

-

- James Davis, special assistant

for research and development to Under Secretary Slezak, warned that

G-4's Research and Development Division was currently too involved in

administrative details. What was needed was an agency devoted to

original studies and analyses which would bring together problems of

new weapons or equipment needed in combat with new technical ideas. This

would give concrete direction to the research and development program.

For years relating weapons and technology had been swept under the rug

as a secondary mission of the Army schools, which were also so isolated

from technology and science that they could not perform the function

properly.60

-

- The Palmer Reorganization and

the new Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics represented another defeat

for those who demanded separation of research and development from

logistics.

The deputy chief now supposedly had greater control over the operations

of the technical services, including research and development, than

before. The scientists, led by Dr. Killian, refused to surrender. A

Congressional investigation of the Defense Department's research and

development programs under Congressman R. Walter Riehlman, Republican of

New York, supported their efforts. General Uncles, Dr. Killian, and Dr.

Bush in testimony before this group publicly ventilated the arguments

they had been urging within the Army staff.61

-

- The Riehlman Committee's report

warned that "unless the military departments, and our military

leaders in particular, choose to correct these problems caused largely

by military administrative characteristics, the forces of logic and

civilian scientific dissatisfaction could well dictate that research and

- [251]

- development be rightly

considered incompatible with military organization.62

-

- The report also discussed the

Davies Committee recommendations, concluding that the Secretary of the

Army's plan had treated the problem too superficially. It agreed with

Dr. Killian and other scientists that research and development were

incompatible with logistics and that the Army Scientific Advisory

Panel should be strengthened in numbers and authority. It urged creation

of an additional Assistant Secretary for Research and Development and

criticized the Department of the Army for failing to "attract

adequate support and interest from civilian scientists" largely

because of massive red tape and an apparent lack of interest in the

subject.63

-

- The struggle entered a new phase

when the now permanent and expanded Army Scientific Advisory Panel

(ASAP) held its first formal meeting on 16 November 1954. It discussed

the continued conflict between the Deputy Chief of Staff for Plans and

Research and the new Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics over the

research and development program. The new Assistant Secretary for

Logistics and Research and Development, Frank Higgins, a former

president of the Minneapolis Grain Exchange, concluded that "the

Army Research and Development Program, especially at the top, should be

reorganized without delay." 64

-

- Dr. Killian, as chairman of the

Army Scientific Advisory Panel, then personally urged Secretary Stevens

to separate research and development from logistics and raise the status

of the Chief of Research and Development to the Deputy Chief of Staff

level. Secretary Stevens finally agreed, and on 28 December 1954 all

research and development functions and responsibilities assigned to

the Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics were transferred to the Deputy

Chief of Staff for Plans and Research. A new General Staff division

under a Chief of Research and Development would be responsible for

"planning, supervising, coordinating, arid directing" all Army

research and development.65

- [252]

- The new organization was not

satisfactory because both the Assistant Secretary for Logistics and Research and Development and the Deputy Chief of Staff

for Plans and Research were overburdened with work. The McKinsey and

Company report of March 1955 said that the Army should create a new

Research and Development Directorate, relieving the existing Assistant

Secretary for Logistics of this burden. The Second Hoover Commission of

1955 recommended assigning to the Assistant Secretary for Logistics

responsibility for almost all Army logistical functions, including

research and development and supervision of the technical services,

removing these functions entirely from the General Staff.

-

- Brig. Gen. Andrew P. O'Meara,

the new Chief of Research and Development, on 3 August 1955 formally

proposed creating a new deputy chief of staff for Research and

Development. The Army staff agreed, including Lt. Gen. James M. Gavin

and General Palmer, who had become Vice Chief of Staff. The new

Secretary of the Army, Wilber M. Brucker approved, and the new office

began operations on 10 October 1955 with General Gavin appointed as the

Army's first Chief of Research and Development. A new civilian post, the

Director of Research and Development, was created on 3 November 1955

at the assistant secretary level. Dr. William H. Martin, then Deputy

Assistant Secretary of Defense for Applications Engineering, became

the first director.66

-

- Despite these changes the Deputy

Chief of Staff for Logistics still controlled the technical services,

including their budgets and personnel. As the historian of OCRD noted:

-

- The Chief of Research and

Development had little or no say in the placement of personnel . . . in

responsible research and development positions within the Technical

Services. And even if he were consulted there was no means by which he

might reward outstanding effort or penalize unsatisfactory performance.

-

- A management subcommittee of the

Army Scientific Advisory Panel in the fall of 1958 concluded it was

unrealistic "to expect the Chief of Research and Development to

assume responsibility for success in this field without having direct

control

- [253]

- over funds, personnel, and

facilities to accomplish his mission." 67

The full ASAP urged

that the Chief of Research and Development have sole responsibility for

all policy decisions in his area and sole control of funds required to

carry out his missions, including the construction, evaluation, and

testing of prototypes.

-

- Another development came with

the announcement by the Department of Defense in November 1958 that

beginning with fiscal year 1960 all research and development

appropriations as well as identifiable research and development

activities under other budget programs would be included in one new

research,

development, test, and evaluation budget category.68

-

- During this same period the ASAP

conducted a series of studies and held conferences aimed at reducing the

lead time between the point when a new weapon is conceived and the time

it reaches the soldier on the battlefield. The ASAP believed that much

time was wasted simply in unproductive red tape and that more authority

for the Chief of Research and Development would reduce it.

-

- As an example it took ten years,

from 1950 to 1960, for the Army to produce a replacement for the World

War II amphibian veteran known as the DUKW. Research was not involved,

just development engineering. The Ordnance Corps received the assignment

in late 1950. Six years later in 1956 only an unsatisfactory prototype

had been produced. The Transportation Corps in the meantime had produced

a larger amphibian, the BARC, for testing in less than two years.

Disagreement

between the Transportation Corps and Ordnance Department over the type

of smaller amphibian required stalled progress for more than two years.

In late 1958 a contract for developing a prototype of a new small

amphibian, the LARC, was finally negotiated by the Transportation Corps.

Two more years passed, again partly because of continued opposition by

the Ordnance Corps, before the LARC was finally accepted or "type

classified" as standard equipment for

- [254]

- the Army on 20 July 1960. As

this case demonstrated, a major reason for delay in developing new

equipment was disagreement among the technical services.69

-

- ASAP pressure also resulted in

establishing the Army Research Office (ARO) on 24 March 1958 under the

Office of the Chief of Research and Development (OCRD) "to plan and

direct the research program of the Army," to make maximum use of

the nation's scientific talent, to provide the nation's scientific

community with a single contact in the Army, and ensure that the Army's

research and development program emphasized the Army's future needs. ARO

would also coordinate the Army's program with similar programs in the

Navy, Air Force, and other government agencies. Within the Army it would

co-ordinate the research and development programs of the technical

services.70

-

- The next official to grapple

with the issue of control over the technical services' research and

development programs was the Army's new Director for Research and

Development, Richard S. Morse, formerly president of the National

Research Corporation and vice chairman of the Army Scientific Advisory

Panel. The 1958 reorganization of the Department of Defense had created

a Director of Defense Research and Engineering. President Eisenhower

had also established a special White House Assistant for Science and

Technology, appointing Dr. Killian, former chairman of ASAP, to that

post. These events led Mr. Morse to suggest a complete reevaluation of

the Army's research and development organization. Lt. Gen. Arthur G.

Trudeau, General Gavin's successor as Chief of Research and Development,

agreed. Following recommendations from the Chief of Staff, General

Lyman L. Lemnitzer, Secretary Brucker appointed a seven-man board under

the Assistant Secretary for Financial Management, George H. Roderick.

The Roderick Board, which included Mr. Morse, General Trudeau, and Lt.