- When General George C. Marshall became Chief of Staff in 1939, he inherited

not only the staff structure sketched in the previous chapter, but also

a set of planning assumptions on the nature of the next war laid down

in the Harbord Board report. The basic assumption was that any new war

would be similar to World War I and would require similar command and

management methods. In fact the circumstances of World War II would differ

radically from those of World War I, and this difference made the Harbord

Board doctrine and the planning based upon it almost irrelevant from the

start. In the prewar period, 1939-41, the War Department struggled along

trying to adapt the Harbord concepts to the new situation, revising them

piecemeal in response to the immediate needs of the moment. When war came

General Marshall determined to sweep the entire structure aside and develop

a new and radically changed organization adapted to the circumstances

of World War II.

-

- The Harbord Board had assumed that the next war would involve a single

theater of operations, that the Chief of Staff would take the field as

commanding general with the nucleus of his GHQ taken from the War Plans

Division, and that military planning in GHQ would be primarily on tactics

for a one-front war. It took into consideration neither the new importance

of air power and armor, nor the necessity for genuinely joint operations

with the Navy or combined operations with the Allies. The board also assumed

there would be a single M-day (mobilization day) on which the United States

would change overnight from peace to war as in April 1917, a concept which

dominated mobilization planning between the two wars. Instead the nation

gradually drifted from neutrality to active belligerency between September

1939 and December

- [57]

- 1941, and the war developed as a global affair on many fronts involving

combined ground, air, and naval forces. A complicated series of combined

arrangements with the British evolved, and the Army found itself, from

1939 onward, caught up in vital questions of global political and military

strategy for which it was not thoroughly prepared.1

-

- Probably the most important assumption of the Harbord Board was one

never stated, but clearly implied: that the President and Secretary of

War would follow the practice of Woodrow Wilson and Newton D. Baker in

delegating broad authority for the conduct of the war to professional

military officers. This was a questionable assumption since President

Wilson was the only President in American history who did not play an

active role as Commander in Chief in wartime. President Franklin D. Roosevelt's

decision to exercise an independent role in determining political and

military strategy was more consistent with the traditional concept of

the President as Commander in Chief developed by George Washington, James

Madison, James K. Polk, Abraham Lincoln, and William McKinley. Even if

Roosevelt had not deliberately chosen to play an active role, the vital

political issues raised by World War II would have forced him to do so.

Every major decision on military strategy was almost always a political

decision as well and vice versa. There was, consequently, no clear distinction

between political and military considerations during World War II, although

many, including the President himself at times, imagined there was one.

-

-

- Since President Roosevelt played an active role as Commander in Chief,

he dealt directly with General Marshall rather than through the Secretary

of War. General Marshall's primary role became that of the President's

principal Army adviser on military strategy and operations. As a result,

the Chief of Staff also became the center of authority on military

matters within

- [58]

- MARSHALL AND STIMSON. (Photograph taken in 1942.)

-

- the department. This fact at first complicated Marshall's relations

with his titular superior, the Secretary of War. It also had important

consequences ultimately for the position of the Under Secretary of War

charged with procurement and industrial mobilization.2

-

- There were other complications. When Marshall became Chief of Staff

a bitter feud between Secretary Harry H. Woodring, a forthright, impulsive

Middle Western isolationist, and Assistant Secretary Louis A. Johnson,

an ambitious, active interventionist, had demoralized the department and

reduced the Office of the Secretary of War to a position of little con-

- [59]

- sequence. This feud placed General Marshall in an impossible situation

which the President's delay in dealing with it made worse. Roosevelt finally

removed Woodring in June 1940, and for personal and political reasons

replaced him with a Republican, Henry L. Stimson, previously Secretary

of War, as well as a colonel in the AEF, Governor-General of the Philippine

Islands, and Secretary of State. Stimson's great personal prestige and

distinction as an elder statesman in the Root tradition became the basis

for his real authority within the department rather than his ambiguous

official position under a President who frequently acted as his own Secretary

of War.3

-

- Although the relations between the Secretary and the Chief of Staff

were strained at first by the President's policy of dealing with the latter

directly, Stimson and Marshall soon reestablished the alliance between

the Secretary and Chief of Staff initiated by Mr. Root. Friction then

gave way to a close personal relationship based upon mutual respect.

-

- The Secretary and the Chief of Staff worked out an informal division

of labor in which the general concentrated on military strategy, operations,

and administration, while Stimson dealt with essentially civilian matters

less directly related to the conduct of the war. Manpower problems, scientific

developments, civil affairs, and atomic energy were among the most important

of Stimson's concerns. On these and similar issues he acted as liaison

between the Army and the heterogeneous collection of civilian agencies

created from time to time to help direct the war on the home front. He

also ran political interference for the general, protecting him from importunate

congressmen, politicians, and businessmen. Sharing essentially the same

values and priorities, Stimson and Marshall were a unique team in an environment

where competition rather than co-operation was the general rule. The Secretary

at the end of the war expressed his feelings to Marshall, saying: "I

have seen a great

- [60]

- many soldiers in my lifetime, and you, sir, are the finest soldier I

have ever known."4

-

- Mr. Stimson was fortunate in being able to recruit his own personal

staff, and he gradually reorganized the secretariat as he saw fit in 1940

and 1941. He chose judge Robert P. Patterson as Assistant Secretary (later

Under Secretary) of War in charge of industrial mobilization and procurement.

Robert A. Lovett became Assistant Secretary of War for Air and John J.

McCloy a special Assistant Secretary who acted as a troubleshooter on

intelligence, lend-lease, and civil affairs. A personal friend of Stimson's,

Harvey H. Bundy, became a special assistant who dealt with scientists

and educators, and Dr. Edward L. Bowles of the Massachusetts Institute

of Technology, designated officially as the Secretary's Expert Consultant,

worked on radar and electronics. From the ranks of these men chosen by

Stimson came the civilian leadership in defense policy in the postwar

period.5

-

- Below the Secretary and his personal staff lay a permanent civilian

secretariat. The Chief Clerk (later designated the Administrative Assistant

to the Secretary) , John W. Martyn, was a veteran of long service. His

office was responsible for a heterogeneous collection of War Department

administrative functions, including civilian personnel administration,

the expenditure of contingency funds, procurement of general nonmilitary

supplies and services for the department, the development of internal

accounting procedures, and the control of administrative forms used in

the department.

-

- The Bureau of Public Relations was directly attached to the Secretary's

office. Later it was transferred to the Army Service Forces and at the

end of the war made a War Department Special Staff division. Its Industrial

Services Division was responsible for publicity on labor relations. In

November 1940 the President appointed a Civilian Aide for Negro Affairs,

Judge William H. Hastie, who worked under Mr. McCloy. The Panama Canal

Zone and the Board of Commissioners of

- [61]

- the United States Soldiers' Home were two agencies outside formal War

Department channels that reported directly to the Secretary of War for

administrative purposes.6

-

- Congress redesignated the position of the Assistant Secretary of War

as the Under Secretary of War on 16 December 1940. At the beginning of

the war in Europe this office had about fifty officers engaged in planning

for industrial mobilization. By the end of 1941 the staff had expanded

to 1,200 officers and civilians. The Planning Branch consisted of eleven

divisions, and separate branches were created for Purchase and Contract,

Production, and Statistics. It was responsible for dealing with the rapidly

proliferating civilian mobilization agencies created by the President,

particularly the War Production Board. The Office of the Assistant Chief

of Staff, G-4, which dealt with the Under Secretary on military procurement,

also found it necessary to expand its organization and operations. At

first primarily a planning agency it quickly became an operating agency

engaged in directing and co-ordinating activities of the supply

services.7

-

-

- Unlike Secretary Stimson General Marshall initially could not choose

his own staff nor organize it as he saw fit, and while the secretariat

took shape in 1940-41 the General Staff bogged down and had to undergo

a radical reorganization after Pearl Harbor. Marshall inherited an organization

prescribed by Congress in the National Defense Act amendments of 1920.

It was adequate for a small peacetime constabulary force with Congress

tightly controlling the expenditure of every dollar. It proved inadequate

for the conduct of a major war. As one historian has described it:

-

- By 1940 the military establishment had grown into a loose federation

of agencies-the General Staff, the Special Staff for services, the Overseas

Departments, the Corps areas, the Exempted Stations. Nowhere in this

- [62]

- federation was there a center of energy and directing authority. Things

were held together by custom, habit, standard operating procedure, regulations,

and a kind of genial conspiracy among the responsible officers. In the

stillness of peace the system worked.8

-

- By mid-1941 approximately sixty agencies were reporting to the Chief

of Staff directly, creating management problems and administrative bottlenecks

potentially as monumental as those that had developed in 1917. Marshall's

role as general manager of the department was interfering with his duties

as the President's adviser on military strategy and operations.9

-

- After World War I several major industries in expanding and diversifying

their operations had faced similar management problems. There was little

effective control because top executives were preoccupied like General

Marshall with daily administrative details to the detriment of over-all

control. Major policy decisions were made on an ad hoc basis by compromise

and bargaining among executives, each more concerned with his own area

of operating responsibility than with the interests of the whole organization.

-

- The managers of E. I. DuPont de Nemouxs & Co., Inc., General Motors

Corp., and Sears Roebuck & Co. solved these problems by combining

centralized control over policy with decentralized responsibility for

operations. Control was centralized in a group of top executives without

operating or administrative responsibilities, who concentrated on major

policy decisions, planning future operations, allocating resources accordingly,

and reviewing the results, a technique later referred to as "planning-programming-budgeting."

Responsibility for operations was decentralized to field agencies. In

one case, Sears, the experiences of the War Department General Staff under

General March in World War I seem to have been a factor in the development

of a modern corporate organization.

- [63]

- Engineering the reorganization for Sears was Robert E. Wood, General

Goethals' Quartermaster General in World War I.10

-

- General Marshall's experience as Chief of Staff in 1939-41 led him to

the same general conclusion on the necessity for centralized over-all

control and decentralized responsibility for operations if the War Department

and the Army were to function effectively. After World War I he had foreseen

that members of the General Staff might become "so engrossed in their

coordinating and supervisory functions" that they would neglect their

primary missions of preparing war plans and tactical doctrine.11

In

the two years before Pearl Harbor the War Department staff, including

the General Staff, became a huge operating empire increasingly involved

in the minutiae of Army administration. The pressing requirements of the

moment eliminated all other considerations. 12

-

- Co-ordinating the technical services, for example, was difficult because

of the complicated division of responsibility for their activities among

the General Staff. Not only did they report to the Under Secretary on

industrial mobilization and planning, but also to each of the General

Staff divisions: G-1 on personnel, G-2 on technical intelligence, G-8

on training, and to G-4 only on supply requirements and distribution.

The new lend-lease program of all aid short of war to the Allies created

further complications, and a special Defense Aid Director was established

in the department to co-ordinate this function among the numerous agencies

concerned with it. Still another problem was created by the Army Air Forces'

drive

- [64]

- for autonomy including separate administrative and supply agencies.13

-

- Serious delays in military camp construction led to the transfer of

responsibility for this function and for construction of airfields and

other installations from an overburdened Quartermaster Corps to the Corps

of Engineers, a transfer made permanent by law in December 1941.14

-

- To assist him in administering the department, Marshall added in 1940

two additional Deputy Chiefs of Staff. The existing Deputy Chief, Maj.

Gen. William Bryden, was responsible for general administration of the

department and the Army. Maj. Gen. Henry H. Arnold, Chief of Army Air

Forces, served also as Deputy Chief of Staff for Air and participated

with Marshall in the development of joint strategy. After Pearl Harbor

Arnold became a member of the joint and Combined Chiefs of Staff. This

arrangement reflected Marshall's appreciation of the Air Forces' desire

for autonomy.15

-

- Maj. Gen. Richard C. Moore became Deputy Chief of Staff for supply,

construction, and the newly designated Armored Force. Congress, acting

on General Pershing's recommendation, had deprived the Tank Corps, created

during World War 1, of its status as a separate combat arm. Between the

wars the roles and missions of the armored forces in this country as in

Europe were the subject of bitter internal dissension within the Army.

The strongest opposition to the tank came naturally from the Cavalry whose

chief, Maj. Gen. John K. Herr, in 1938 urged:

- [65]

- "We must not be misled to our own detriment to assume that the

untried machine can displace the proved and tried horse."16

-

- Asking Congress for authority to re-create a separate armored force

risked public ventilation of this dispute within Army ranks. This in turn

might have embarrassed the Army in its efforts to obtain Congressional

support for expanding the Army to meet the threat of Axis aggression.

Consequently, the Armored Force came quietly into existence at Fort Knox,

Kentucky, on 10 July 1940 by direction of the Secretary of War. Congress

did not designate the Armored Force as a separate combat branch until

the Army Organization Act of 1950 when as the Armor Branch it officially

replaced the horse cavalry. General Herr went to his grave asserting the

Army had betrayed the horse.17

-

- The man who delivered the coup de grace to the horse was an ardent

armor supporter, Brig. Gen. Lesley J. McNair. General Marshall personally

selected him as his deputy in charge of General Headquarters, when it

was activated in July 1940. The primary mission of GHQ was to raise and

train the new Army, but, in accordance with the Harbord Board concept,

it was also supposed to become the commanding general's military operations

staff in the event of war.

-

- General McNair set up his headquarters across town from the War Department

in the Army War College. As in 1917 physical separation from the War Department

as well as preoccupation with training made it difficult for GHQ to maintain

effective personal contact with General Marshall and to keep up with the

rapidly changing complexion of the war. It was the War Plans Division,

physically close by, upon which Marshall came to rely for immediate assistance

in planning and preparing for military operations.18

- [66]

- Such was the jury-rigged, extempore manner in which the War Department

under General Marshall organized for war. He had hoped to change things

in this manner gradually without publicity or stirring up antagonisms

among powerful interests groups like the chiefs of the supply services.

Tinkering with the machinery did not produce satisfactory results, and

two days after Pearl Harbor Marshall asserted that the War Department

was a "poor command post."19

-

- The pressing need, he later said, was for "more definite and positive

control by the Chief of Staff." The General Staff, as he had warned,

"had lost track of the purpose of its existence. It had become a

huge, bureaucratic, red tape-ridden, operating agency. It slowed down

everything." 20

Too many staff

divisions and too many individuals within these staff divisions had to

pass on every little decision that had to be made by the Chief of Staff.

"It took forever to get anything done, and it didn't make any difference

whether it was a major decision" or a minor detail.21

The Chief

of Staff and the three deputy chiefs were "so bogged down in details

that they were unable to make any decisions."

-

- You had so many different people in there that there wasn't anybody

who could get together and make a decision . . . . The Cavalry didn't

agree that an Infantryman could ride on a tank; the Infantry said "Yes,

we have some tanks, and we can ride tanks." General Herr said "Anybody

who wants to ride in a tank is a damn fool. He ought to be riding a horse."

And it was almost impossible to get a decision. There were too many people

who had too much authority.22

-

-

- The decision General Marshall reached was to substitute the vertical

pattern of military command for the traditional horizontal pattern of

bureaucratic co-ordination. This centralization of executive control would

enable him to decentralize operating responsibilities. He would then be

free, like

- [67]

- the top managers of DuPont, General Motors, and Sears, to devote his

time to the larger issues of planning strategy, allocating resources,

and directing global military operations.23

-

- Instead of the General Staff and three score or more agencies with direct

access to the Chief of Staff's office, the Marshall reorganization created

three field commands outside the formal structure of the War Department:

Army Ground Forces (AGF), Army Air Forces (AAF), and Army Service Forces

(ASF), initially the Services of Supply. Army Ground Forces under Lt.

Gen. Lesley J. McNair, responsible for training the Army, and Army Air

Forces under Lt. Gen. Henry H. Arnold were for practical purposes already

functioning, the former under its designation of General Headquarters.

Army Service Forces under Lt. Gen. Brehon B. Somervell was an agency new

to World War II and hastily thrown together to include the Army's supply

system, administration, and "housekeeping" functions within

the United States. With the creation of these commands, said Maj. Gen.

Joseph T. McNarney, who became the Deputy Chief of Staff in March 1942,

"Immediately 95 per cent of the papers that came up to the General

Staff ceased just like that." 24

During the war both ASF and AAF

operated as integral parts of the War Department because they were intimately

involved in military planning. AGF, on the other hand, remained a field

command separate from the War Department.

-

- The War Plans Division (soon renamed the Operations Division) became

General Marshall's command post or GHQ. The rest of the General Staff,

drastically reduced in numbers, were forced out of operations and confined

in theory to a broad policy planning and co-ordination role for which

their long, drawn-out staff procedures were more appropriate. General

- [68]

- Marshall insisted on this change and had disapproved earlier reorganization

proposals because they offered him little relief from administrative details

that came up to his office through the General Staff. Without such a reduction

in personnel the General Staff would work its way back into operations,

and Marshall was certain the whole reorganization would be a failure.25

-

- The Marshall reorganization also abolished the offices of the chiefs

of the combat arms, the offspring of the National Defense Acts of 1916

and 1920, as an unnecessary staff layer and gave their powers to Army

Ground Forces which emphasized integrating the several arms into a single,

unified fighting team. Among other things the creation of AGF was a triumph

of the infant armored forces over the cavalry and field artillery. General

Herr regarded armored forces advocates as betraying the horse, as mentioned

earlier. Maj. Gen. Robert M. Danford, the Chief of Field Artillery, the

only combat arms chief to record his objections in writing, obstinately

insisted that field artillery remain horse-drawn. One argument repeatedly

made within field artillery was that horses could feed off the land, while

motor trucks could not.26

-

- This streamlined structure required equally streamlined staff procedures.

Out for the duration were formal staff actions with their elaborate, time-consuming

processes of concurrence, cognizance, and consonance, except in special

circumstances where they were appropriate. Instead procedures were developed

which would produce prompter and more effective decisions and action.

The three major commands were also urged to use "judicious shortcuts

in procedure to expedite operations." 27

-

- In approving this reorganization General Marshall achieved

- [69]

- GENERAL McNARNEY

-

- the same results as General March had in World War I of sweeping aside

accustomed procedures. Unlike March, Marshall achieved these results without

arousing widespread opposition both within and outside the department.

-

- The Marshall reorganization actually had a rather long period of gestation,

its basic outline having been proposed by Lt. Col. William K. Harrison,

Jr., of WPD sometime in the fall of 1940.28

The Harrison plan came up

for formal discussion within the War Plans Division in the summer of 1941.

Brig. Gen. Leonard T. Gerow, Chief of the War Plans Division, vetoed the

Harrison plan at this point because it involved "extensive experimentation

with untried ideas in a critical time." 29

-

- A conflict between the missions and responsibilities assigned General

Headquarters and Army Air Corps came to a head in the fall of 1941 and

was responsible for General Marshall's decision to scrap the cumbersome

existing organization of the General Staff. What was really at issue was

the Air Corps' determined drive for complete autonomy within the Army.

The

- [70]

- War Plans Division defeated Air Corps attempts to set up a separate

air planning staff independent of WPD. GHQ's control over tactical planning

and operations, specifically over the allocation and tactical employment

of air units in the air defense of the continental United States and certain

bases in the Atlantic and overseas, was another problem. The latter were

already under the formal control of GHQ, and the former would follow in

the event of war.

-

- The solution to this problem, proposed to General Marshall by General

Arnold in mid-November, was to limit GHQ to organizing and training ground

combat forces. Its command and planning functions would be transferred

to WPD as a policy and strategy planning agency with broad co-ordinating

authority over the separate field commands for the future AAF, ground

forces, and supply services. In substance this scheme followed the plan

earlier proposed by Colonel Harrison. General McNair himself at this point

favored eliminating the existing organization of GHQ as part of a general

reorganization of the War Department. Favorably impressed, General Marshall

ordered WPD to develop the plan in greater detail to determine its practicality.

-

- About a week before Pearl Harbor, Marshall recalled Brig. Gen. Joseph

T. McNarney of WPD, then in London on a special mission, to head a committee

to study and recommend a proper organization for the War Department. When

McNarney reached Washington, President Roosevelt ordered him to serve

on the special Roberts Pearl Harbor Investigating Committee. It was not

until 25 January 1942 that McNarney learned from General Marshall that

he was to take charge of reorganizing the department.

-

- Pearl Harbor and American entrance into the war had intensified the

Chief of Staff's problems and the need for a reorganization. General Marshall

told McNarney he simply couldn't stand the "red-tape" and delay

any longer. What he wanted was "some kind of organization that would

give the Chief of Staff time to devote to strategic policy and the strategic

. . . direction of the war." The First War Powers Act of 18 December

1941, like the Overman Act of 1918, gave the President power to reorganize

the federal government as he saw fit for the duration of the war plus

six months. This gave

- [71]

- General Marshall the opportunity to reorganize the War Department, subject

to Presidential approval.30

-

- After outlining the problem General Marshall turned the pick and shovel

work of devising a practical reorganization plan over to McNarney and

two assistants-Colonel Harrison and Lt. Col. Laurence S. Kuter. The trio

discussed the issues, examined various alternative proposals, and on 31

January General McNarney recommended to the Chief of Staff a modified

version of the Harrison plan. Advising against following traditional General

Staff procedures, McNarney warned that submitting the proposal to "all

interested parties" would result in many nonconcurrences and "interminable

delay." Instead he recommended approving the plan, appointing the

new commanders, and creating an "executive committee" to carry

out the reorganization as soon as possible.

-

- General Marshall announced his approval of the McNarneyHarrison plan

at a meeting of representatives of the General Staff, General Headquarters,

and Army Air Corps on 5 February 1942. Representatives of the chiefs of

the combat arms and services and of the Under Secretary's Office were

conspicuous by their absence. General Marshall said he did not want the

reorganization discussed with the Under Secretary until more detailed

plans had been developed. To avoid stirring up opposition General McNarney

ordered that the reorganization plan be discussed only with those who

had to execute it. This excluded those chiefs of combat arms whose terms

were to expire shortly in any event as well as The Adjutant General, whose

term was also soon to expire. 31

-

- General Marshall's references to the Under Secretary of War's Office

emphasized that the 5 February meeting was the first time representatives

of the Army's supply agencies were consulted about the reorganization.

Although nearly all the reorganization plans proposed and discussed had

advocated a supply or service command, they went no further than the general

proposition that supply should be under a unified command. The McNarney-Harrison

plan, according to Goldthwaite

- [72]

- Dorr, an adviser to General Somervell, looked very much as if it had

been drawn up by a group of officers who did not know much about the Army's

supply system. Army Service Forces thus seems to have emerged largely

as a more or less unplanned by-product of the Marshall reorganization

designed to reduce the number of agencies reporting directly to the Chief

of Staff. It also reflected the tendency of combat arms officers to take

logistics for granted, a tendency which had caused embarrassment during

World War I and would cause further problems in World War II.32

-

- Both the Under Secretary's Office and G-4 had been studying the problem

of supply organization on their own. The same problems that led to the

McNarney-Harrison plan, the administrative burden of increasing mobilization,

red tape, and divided command naturally had affected the Army's supply

system. Under Secretary Patterson asked Booz, Frey, Allen and Hamilton,

a management consultant firm, to suggest improvements in the organization

and operations of his office. Their report, submitted in December 1941,

criticized the divided command over Army logistics and the confused relationship

between the Under Secretary's Office and G-4. Their solution was to appoint

a military officer as "Procurement General" with functions similar

to those of General Goethals in World War I. Mr. Patterson rejected this

solution.

-

- After General Somervell became G-4 in December 1941 he asked Mr. Dorr,

who had served as Assistant Director of Munitions under Benedict Crowell

in World War I, to investigate the Army's supply system informally. Equally

critical of divided command, Dorr also recommended re-creating General

Goethals' position as executive manager of the Army's supply system under

the dual direction of the Under Secretary and the Chief of Staff. 33

-

- By the time General Marshall approved the McNarney-Harrison plan there

was general agreement among top War Department officials on the need for

unified command over

- [73]

- the Army's logistical system. Secretary Stimson and General Marshall

also agreed that General Somervell should be the commanding general of

ASF. 34

-

- The McNarney Committee conferred with Secretary Stimson who likewise

approved the reorganization, suggesting only that Marshall remain Chief

of Staff rather than commander in chief in order to retain the principle

of civilian control. General Marshall then appointed an Executive Committee

to carry out the reorganization headed by General McNarney and including

representatives of the new commands and other agencies with a vested interest

in making the reorganization work. McNarney emphasized that the committee

was not to debate the reorganization but simply to draft the necessary

operational directives to put it into effect as soon as possible. With

a 9 March deadline the committee, meeting behind closed doors, hammered

out the detailed plans. Secretary Stimson sent the draft of an executive

order announcing the reorganization on 20 February to the President, while

General Marshall undertook personally to persuade the President of its

necessity. The President approved the plan with one significant change.

He wanted it reworded to "make it very clear that the Commander-in-Chief

exercises his command function in relation to strategy, tactics, and operations

directly through the Chief of Staff." With this amendment, Executive

Order 9082 of 28 February 1942 officially announced the reorganization

and declared it effective 9 March 1942 for the duration of the war plus

six months under the authority of the First War Powers Act of 18 December

1941. War Department Circular 59 of 2 March 1942 followed this up with

a detailed operational plan for, transferring various agencies and functions

to the new commands.35

-

- The Marshall reorganization enabled the Chief of Staff to concentrate

on the larger issues of the war, while the new commands handled the administrative

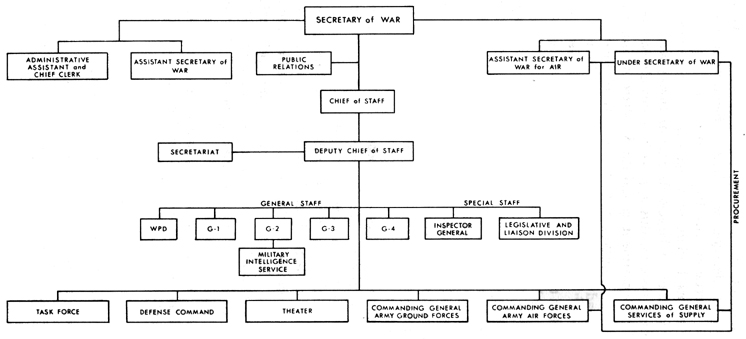

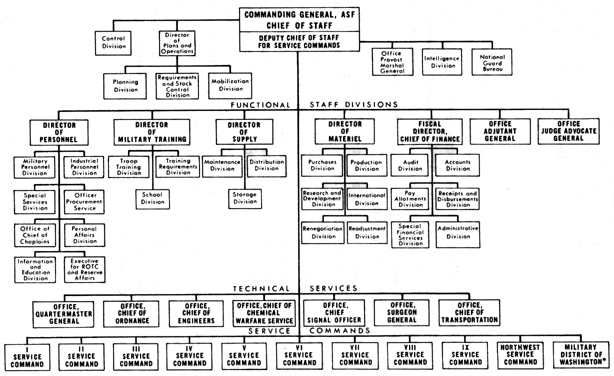

details and operations. (Chart 4) The Chief of Staff now had enough time

to consider the changing strategic complexion of the war and to make his

- [74]

- ORGANIZATION OF THE ARMY (THE MARSHALL REORGANIZATION), 9 MARCH 1942

-

- Source: War Department Circular 59, 2 March 1942.

- [75]

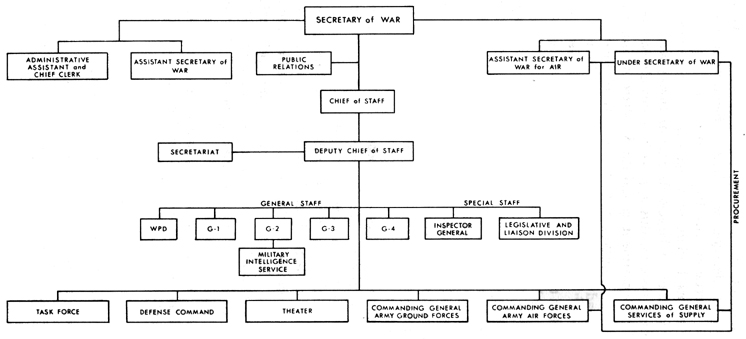

- THE OPERATIONS DIVISION, WAR DEPARTMENT GENERAL STAFF, 12 MAY 1942

-

-

- * This group was called Strategic and Policy Group on 12 May 1942, but

was changed shortly thereafter to Strategy and Policy Group. It has

changed on this chart to conform to the text.

-

- Source: OPD Unit History File

-

- decisions more deliberately. As a result, said General McNarney, the

"decisions were better; they were bound to be."36

-

- The success of any large organization depends upon the ability of its

leaders to select competent subordinates, not merely yes-men. In large-scale

organizations governed by formal promotion systems, this approach is not

always possible, and the War Department contained its share of bureaucratic

incompetents. Assistant Secretary Lovett recalled there was so much "deadwood"

in the department that it was "a positive fire hazard." In reorganizing

the department General Marshall could select the men he wanted as his

assistants, as had Secretary Stimson earlier. General McNarney became

the sole Deputy Chief of Staff and acted as Marshall's general manager

in running the department until McNarney went overseas in October 1944.

McNarney, McNair, Arnold, Somervell, and the principal staff officers

of WPD-OPD were Marshall's men, and upon them he relied heavily in the

development and co-ordination of military strategy. His reputation as

the Army's greatest Chief of Staff depended in no small measure upon his

exceptional judgment of men.37

-

- In summary the main purpose of the Marshall reorganization was to provide

effective executive control over the War Department and the Army. The

rationalization of the department's structure in substituting the vertical

pattern of military command for the traditional horizontal pattern of

co-ordination paralleled similar developments among leading industrial

organizations. However disgruntled those personalities and agencies displaced

by the new dispensation, the officials most. directly responsible for

the management of the Army as a whole testified to its effectiveness.

The complaints came mostly from those responsible for only one aspect

of the war and who resented the restrictions placed on their traditional

freedom of action and autonomy. 38

-

-

- The effectiveness of the reorganization depended on the

- [76]

- effectiveness of the new agencies. The successful conduct of the war

depended most directly on General Marshall's military operations staff,

WPD, which on 23 March 1942 was redesignated the Operations Division (OPD).

Its principal reason for existence was to assist General Marshall in developing

strategy and directing the conduct of military operations. It represented

the Army in dealings with the Navy, the Joint and Combined Chiefs of Staff,

the White House, and civilian war agencies. With the assistance of Army

Ground Forces, Air Forces, and Service Forces OPD calculated the requirements

in men and resources the Army needed to carry out the strategy and plans

hammered out by the joint and combined staffs. It acted as liaison between

the overseas theaters of operations and the War Department, AGF, AAF,

ASF, the Navy, the Joint and Combined Chiefs of Staff, and the home front.

Responsible for planning the Army's global military operations, for determining

and allocating the resources required, and for directing and co-ordinating

their execution, OPD was the Army's top management staff. 39

-

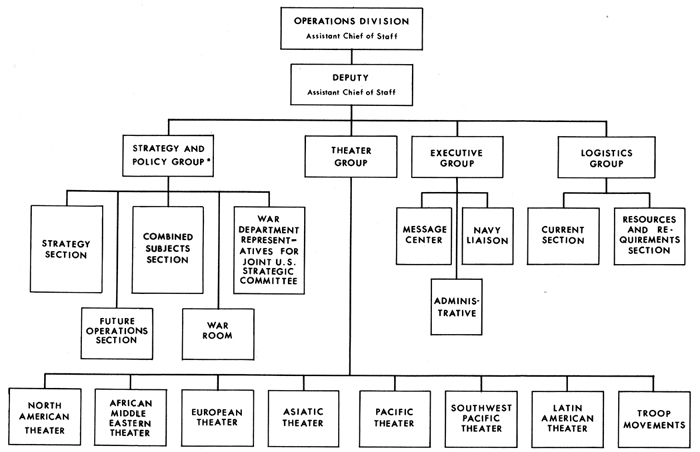

- The Operations Division's internal organization reflected its several

functions. (Chart 5) The Strategy and Policy Group was responsible for

strategy and planning. It provided OPD's representation on the joint and

combined planning staffs and liaison with other war agencies. The Logistics

Group determined the resources required to support projected military

operations. It also represented OPD on those joint and combined committees

responsible for logistical planning. Necessarily, it worked closely with

G-4 and Army Service Forces, and in the process considerable friction

developed between OPD and ASF's Plans and Operations Division. ASF, believing

OPD did not pay sufficient attention to practical logistical problems,

especially the lead time required to produce weapons and other materiel,

sought a greater role in strategic logistical planning. OPD, on the other

hand, resented ASF's attempted intrusions into its areas of responsibility.

-

- OPD's Theater Group was the link between the Army at home and the overseas

theaters, transmitting orders to and re-

- [77]

- laying requests from them. It exercised greater control over theater

operations in the initial stages of their campaigns than later when theater

headquarters had developed their own experienced staffs. An Executive

Group provided personnel and administrative services, including the operation

of OPD's Message Center and Records Section.

-

- With the expansion of the war the activities of these groups in OPD

became so involved that it became necessary to set up a separate Current

Group in February 1944 responsible solely for providing information on

all current OPD operations. It prepared the War Department Daily Operational

and White House Summaries, invaluable to executives for their brevity.

A Pan-American Group was created in April 1945 to deal with the problems

of western hemispheric defense.

-

- The key to OPD's success was its streamlined staff procedure, which

emphasized delegating authority to make recommendations or take action

to the lowest possible level. Personal conferences by designated action

officers, often junior staff members, with responsible officials of other

agencies possessing needed information, replaced written concurrences

submitted through formal staff channels. The belabored decisions reached

by traditional staff procedures would have come too late to have any effect,

and a wrong decision based on hasty research was considered better than

a tardy one based on more thorough study. Special requests for action

from General Marshall required a reply within

twenty-four hours and were known as Green Hornets from their readily identifiable

cover and the consequences of delaying action too long.40

-

-

- The obstacles GHQ encountered before the Marshall reorganization arose

from the confusion of planning and operating functions within the Army

staff. As General Marshall had forecast after World War I the greatest

weakness of the General Staff became its preoccupation with co-ordinating

operations to the detriment of its responsibilities for long-range planning

and the development of tactical doctrine. Instead of revising the

- [78]

- increasingly obsolete Harbord doctrine to meet the radically different

circumstances of World War II, the department, reflecting the reactions

of the nation at large, bumped from one crisis to the next between 1939

and Pearl Harbor, making adjustments here and there according to the needs

of the moment.

-

- The inability to separate planning and operating functions and responsibilities

had been a characteristic vice of the Army and, indeed, of most American

corporate institutions. The failure to make this distinction had hobbled

the General Staff from its inception because it had been assigned both

functions. The only kind of planning most Army officers understood was

operational planning. When they insisted it was both impossible and impractical

to try to separate planning and operations, they clearly meant immediate

operational planning. With little experience in broad, long-range planning

and policy-making and confined to the isolated present, they ignored the

hypothetical future whose consideration almost always yielded to the demands

of the moment. As a consequence the Army lagged behind in just those areas,

such as research and development of weapons and other materiel and the

development of tactical doctrine, where long-range planning was

important.41

-

- The Marshall reorganization did not settle the issue of separating planning

from operations within AGE General McNair settled that issue himself.

-

- The reorganization directive ordered AGF headquarters to separate these

two functions. A small general staff, like the reduced War Department

General Staff, was supposed to be responsible for basic policy decisions

and not become involved in administration or operations. Under its supervision

there was to be a functionally oriented operating staff responsible for

personnel, operations and training, materiel requirements, transportation,

construction, and hospitalization and evacuation.

-

- From the beginning AGF headquarters protested that this

- [79]

- separation was artificial and impractical. Its general staff could not

plan without information from the operating divisions, while the operating

divisions felt they were better qualified to plan because they were in

closer touch with operations. This arrangement also confused relations

with subordinate commands and the technical services which were also organized

with no distinction between planning and operations. Inevitably the AGF

general staff became involved in operations and the operating divisions

in planning.

-

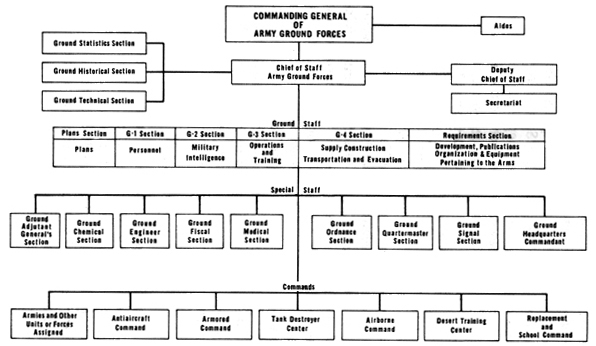

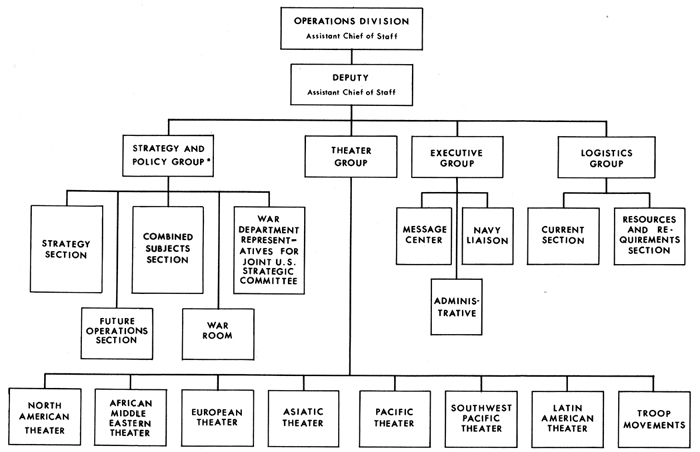

- It was not long before General McNair complained officially to General

Marshall that separating planning and operations was inefficient and productive

only of duplication, delay, and confusion. With General Marshall's assent,

the AGF staff reverted in July 1942 to the traditional pattern, adding

a Requirements Section responsible for developing new weapons and tactical

doctrine. What remained of the offices of the chiefs of the combat arms

had been absorbed in March by the Requirements Section, but in the July

1942 reorganization they disappeared entirely.42

(Chart 6)

-

- Army Ground Forces success depended ultimately on the effectiveness

of the tactical doctrines it developed because they, in turn, determined

the training the Army received and the requirements for new weapons and

equipment. The Armored, Airborne, and Amphibious Commands and the Tank

Destroyer, Mountain, and Desert Training Centers, integrating all the

combat arms, were created because these were the areas where AGF concentrated

its efforts in the development of new doctrine. They symbolized, in fact,

these new doctrines. The testing of weapons and equipment by the Combat

Arms and Technical Services Testing Boards and by the several combined

arms commands and centers during maneuvers was all carried out within

the framework of approved tactical doctrine. The schools disseminated

these doctrines throughout the Army.

-

- The AGF staff sections responsible for tactical doctrine, training,

and requirements for new weapons and material were G-3 and Requirements.

These two sections accounted for half of AGF headquarters officer strength.

While G-3 concentrated on training and the Requirements Section on new

weapons and equipment, they functioned as a single staff unit in the

- [80]

- ORGANIZATION OF THE ARMY GROUND FORCES, OCTOBER 1943

-

-

- Source: Nelson, National Security and the General Staff, p. 407.

- [81]

- development of tactical doctrine, tables of organization and equipment,

and the preparation of training manuals.

-

- In training and tactical doctrine the influence of AGF within the Army

was paramount. Responsibility and authority for the development of new

weapons and equipment, on the other hand, were divided among many agencies

within and outside the Army. The Requirements Section represented the

AGF in negotiations with other War Department agencies concerned with

weapons development such as the Research and Development Division of Army

Service Forces, the technical services, G-4, and later the New Developments

Division of the War Department Special Staff, a troubleshooting agency

designed to expedite tile production of new equipment and its delivery

to the battlefield. Outside the Army the Requirements Section maintained

liaison with the National Inventors' Council and the National Defense

Research Committee, which operated under Dr. Vannevar Bush's Office of

Scientific Research and Development. Representing the military consumer,

the Requirements Section was responsible for assuring that the requirements

of tactical doctrine received adequate consideration in decisions regarding

new weapons and equipment. AGF's approved tactical doctrine, for instance,

dictated that in developing tanks maneuverability was more important than

firepower or armor. Durability and ease of maintenance on the battlefield

were two other AGF priorities.43

-

-

- The Marshall reorganization was a major milestone on the Army Air Forces

road to complete separation from the Army. Now separate from the ground

combat forces, the AAF directed its future efforts toward divorcing itself

from the Army Service Forces and the technical services. By the end of

the war it had succeeded in integrating the majority of some 600,000 Air

technical service personnel into its own organization.

- [82]

- The immediate reason the Air Forces supported reorganizing the War Department

had been its tangled relations with General McNair's GHQ organization.

The autonomous status inherent in the creation of a separate Assistant

Secretary of War for Air and General Arnold's later elevation to Acting

Deputy Chief of Staff for Air did not apply to lower staff or command

levels. The Air Staff was still subordinate to the Army's General Staff,

and the Air Force Combat Command (formerly GHQ Air Force) was nominally

subordinate to General McNair's GHQ as well as the Air Staff. The Air

Corps proper, responsible for training, logistics, and overseas movement

of men and materiel, had a greater degree of autonomy.

-

- In addition to separating Army Air Forces from Army Ground Forces the

Marshall reorganization promised to improve the former's status further

by providing for equal Air Forces representation on the General Staff,

including OPD, and on the various joint and combined staffs. Furthermore

the presence of RAF representatives on the British Joint Staff Mission

made it virtually necessary to appoint General Arnold as a member of the

joint and Combined Chiefs of Staff. 44

-

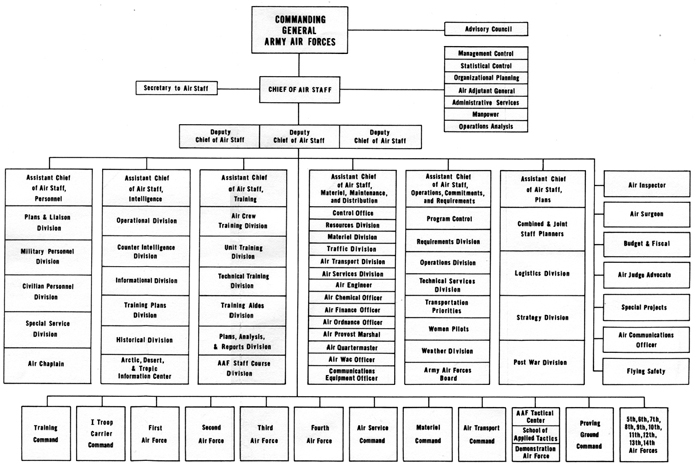

- The reorganization presented AAF headquarters with the same problem

as AGF headquarters-how to separate staff and operating functions. The

Air Staff as a policy planning staff was to be distinct from a group of

operating directorates, responsible for military requirements, transportation,

communications, and personnel. There was also a Management Control Directorate,

responsible for administrative services, organizational planning, and

statistical controls.

-

- AAF headquarters reached the same conclusion as AGF, that it was impractical

to separate planning and operations, and in a reorganization in March

1943 it reverted to the familiar Pershing pattern. There were the usual

Assistant Chiefs of the Air Staff for Personnel, Intelligence, Training,

Logistics, and Planning as well as an additional Assistant Chief for Operations,

Commitments, and Requirements with functions similar to AGF's Requirements

Section. Plans Division personnel

- [83]

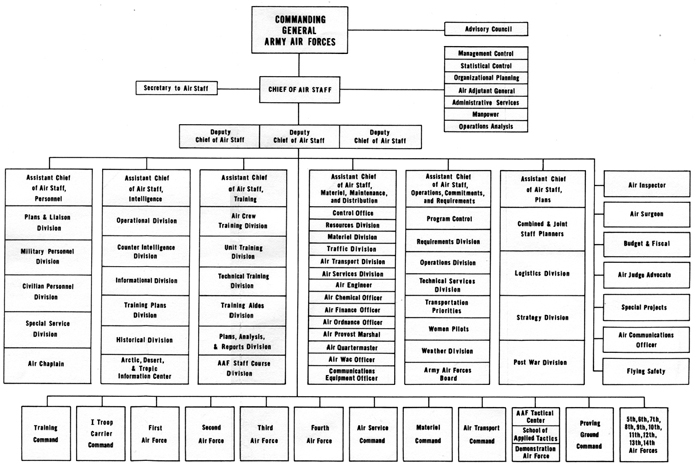

- ORGANIZATION OF THE ARMY AIR FORCES, OCTOBER 1943

-

-

- Source: Nelson, National Security and the General Staff, p.411

-

- were assigned as AAF representatives to OPD and the various joint and

combined staff committees. An important difference with the Army at the

special staff level was the separation of personnel management from the

Air Adjutant General who was placed under the Management Control Directorate.

This basic organization remained stable for the remainder of the war.45

(Chart 7)

-

- The Management Control Directorate, now attached to the Office of the

Commanding General, AAF, borrowed heavily from the experiences of the

aircraft industry. The relationship between the AAF and the aircraft industry

was a uniquely close one. They had grown up together and were mutually

dependent on each other. The AAF had few traditions to hamper development

along new and untried lines, including the development of modern industrial

management control techniques.

-

- The principal divisions of the AAF's Management Control Directorate

included the Air Adjutant General's Office and the Administrative Services

Division which it absorbed, a Manpower Division, an Organizational Planning

Division, a Statistical Control Division, and an Operations Analysis Division.

Except for the Adjutant General's Office and Administrative Services Division,

the staff of the directorate was composed largely of civilian management

experts.

-

- The Manpower Division, established in March 1943 as a result of the

developing nationwide manpower shortage, was responsible for promoting

the efficient utilization of all personnel, military and civilian, by

eliminating unnecessary duplication of effort and nonessential functions,

simplifying administrative procedures, and releasing general service military

personnel for overseas combat duty by replacing them with members of the

Women's Army Corps (WAC), those on limited service, and civilians not

subject to the draft. It prepared job analyses and descriptions to determine

the exact number of individuals by types, both military and civilian,

required to perform efficiently the functions of any Air Force

- [84]

- unit or installation. It controlled manpower levels in the field, while

the Organizational Planning Division controlled manpower authorizations

in AAF headquarters.46

-

- As its name implied, the Organizational Planning Division was responsible

for analyzing and recommending the proper allocation of functions within

the AAF. The internal organization of the Organizational Planning Division

into Training and Operations, Intelligence, and Supply and Transport Branches

reflected the functional organization of AAF headquarters. This division

supervised the preparation of organization charts and promoted decentralized

operations, the elimination of duplication, the clarification of functional

responsibilities, and other measures to provide more effective co-ordination

and administration. A Publications Branch reviewed, edited, and issued

all AAF administrative publications, a function of the Adjutant General

elsewhere in the Army.

-

- The Organizational Planning Division planned and coordinated the AAF

headquarters reorganization of March 1943. It developed the three directorate

system-plans and operations, administration, and supply and maintenance-adopted

by all continental air forces and commands in 1944. It planned and co-ordinated

the complete integration into the Army Air Forces of those technical service

personnel assigned to it who still retained their original technical service

identities. In its own opinion this was the most significant move taken

after the reorganization toward the avowed goal of a completely separate

air force.47

-

- The Statistical Control Division endeavored to consolidate, standardize,

and rationalize the many disparate reporting systems within the AAF, particularly

in the fields of personnel, materiel development, and training. By 1945

it had succeeded in centralizing control over statistical reporting to

such an extent that it could decentralize some of its operations to the

- [85]

- field. The statistics obtained were indispensable also in establishing

effective program controls and in evaluating air operations. At the end

of the war the AAF's statistical controls were the most sophisticated

and effective of all the armed services.48

-

- In December 1942 General Arnold directed establishment of an Operations

Analysis Division (OAD) within the Management Control Directorate which

would apply scientific techniques to the problems of selecting strategic

air targets in Germany. The British had pioneered in this area, known

then and later as Operations Research. OAD's success led to the creation

of similar units within the headquarters of strategic and tactical air

forces overseas. The development of new weapons and other materiel and

the improvement of tactical doctrine were other areas in which the AAF

employed the techniques of operations research.49

-

- Co-ordinating the development, production, and ultimate combat deployment

of aircraft and the highly technical training required for their operation

and maintenance proved extremely difficult. Program monitoring, as this

process was then called, was the progenitor of contemporary systems for

project management. From a purely administrative standpoint the problem

created by these programs was that they cut across established lines of

functional and command responsibility. Until the end of the war the AAF

never successfully solved the problem because it did not provide a centralized

agency high enough in the hierarchy of command to co-ordinate and synchronize

the

- [86]

- various program elements effectively. Although the Marshall reorganization

provided for an Assistant Chief of Air Staff for Program Planning on the

Air Staff, after the March 1943 reorganization this responsibility was

buried as a branch of the Allocations and Programs Division under the

Assistant Chief of Air Staff for Operations, Commitments, and Requirements.

-

- The Statistical Control Division performed some of the work needed to

balance requirements and commitments. In late 1942 it studied the requirements

of the strategic air offensive against Germany on the one hand and Japan

on the other. Using this study the AAF balanced resources and aircraft

production schedules between the two programs. On another occasion the

Statistical Control Division found that training of pilots in the United

States was lagging behind the production of combat aircraft because there

were insufficient aircraft available or allocated for training.

-

- Brig. Gen. Laurence S. Kuter, Assistant Chief of Air Staff for Plans,

assumed responsibility in mid-1943 for program planning. The appointment

of Dr. Edmund P. Learned, an economist from the Harvard Graduate School

of Business Administration, as Special Consultant to the Commanding General

of the Army Air Forces for Program Control, followed shortly. The Statistical

Control Division continued to provide essential program control data relating

to training, ammunition expenditure rates, intelligence, and the accuracy

of strategic and tactical bombing programs. Finally in August 1945 an

Office of Program Monitoring was created which reported directly to the

Chief of the Air Staff. Its responsibility was to supervise all AAF programs

including the resources, requirements, allocation, authority, and commitments

involved in the procurement, availability, production, training, flow,

storage, separation or disposition of personnel, crews, units, aircraft,

equipment, supply, and facilities.50

-

- At the end of the war in August 1945, there was another major reorganization

of AAF headquarters in which the Management Control Office as well as

its Organizational Planning

- [87]

- and Operations Analysis Divisions were abolished. The Air Adjutant General

regained control over the Administrative Services Division and publications.

Along with the new Office of Program Monitoring the Statistical Services

Division became a part of the Office of the Secretary of the Air Staff.

The Manpower Division was transferred to the Office of the Assistant Chief

of Air Staff for Personnel. The previously centralized functions of the

Organizational Planning Division were fragmented among the regular staff

divisions of AAF headquarters. The Operations Analysis Division's functions

were transferred to the Assistant Chief of Air Staff for Operations. In

December 1945 the Office of Deputy Chief of Air Staff for Research and

Development was created. This office sponsored the creation of the Research

and Development (RAND) Corporation in 1946 as an independent private corporation

employing civilian scientists on operations research and later broader

systems analysis projects under contract to the AAF.

-

- Brig. Gen. Byron E. Gates, who was Director of Management Control for

most of the war, believed the reason for abolishing his directorate and

its Organizational Planning Division was the resentment created by such

concepts as management and control among tradition-minded military officers.

Other staff agencies resented what they felt was the interference of the

Organizational Planning Branch in their operations, a delicate question

of cognizance. These developments reflected widespread and growing disenchantment

among Army officers with industrial concepts of management control brought

into the AAF and ASF during the war. In the future the civilian administrators

of the Army and its sister services would urge these concepts and practices

on the services against continued military opposition.51

-

- The Air Forces continued drive for complete separation from the rest

of the Army created other organizational problems and conflicts with the

General Staff and Army Service Forces, particularly the technical services.

The development of an AAF personnel system completely separate from the

rest of the Army also led to conflicts with G-1. According to the theory

- [88]

- behind the Marshall reorganization, the Army Service Forces was supposed

to provide services for both AGF and AAF, freeing the latter to concentrate

on their principal mission of providing trained ground and air combat

troops. At the same time, the AAF was assigned responsibility for procuring

and supplying materiel "peculiar to the Air Forces." The definition

of this term led to a running battle between the Air Forces and the Service

Forces. According to one ASF spokesman, "Army Air Forces always regarded

Army Service Forces as a service organization primarily designed for the

Ground Forces and incapable of understanding Air Forces' problems."

52

-

- As mentioned earlier, technical service personnel, while assigned to

the AAF, retained their traditional identity with their parent organizations.

Ordnance Corps technicians worked alongside Air Force armaments personnel,

Signal Corps men with Air Force communications personnel, and supply personnel

of all arms and services with Air Corps supply personnel. Tradition required

the services to draw tight jurisdictional boundaries around their activities

with consequent duplication of effort and waste of manpower. Partially

in the interest of efficiency General Henry H. Arnold in late 1943 requested

the complete integration of technical service personnel into the Army

Air Forces.

-

- Two other jurisdictional disputes with the technical services involved

responsibility for electronic equipment and missiles. Ultimately General

Marshall had to decide these issues personally. In August 1944 he directed

transfer of responsibility for development and procurement of radar and

radar equipment used in aircraft from the Signal Corps to the AAF. A month

later he split responsibility for the development of missiles between

the Ordnance Department and the AAF. While the Ordnance Department would

have responsibility for development of ground-launched missiles which

"depended on momentum," the AAF would be responsible for "guided

or

- [89]

- homing missiles launched from aircraft" or "ground-launched

missiles which depended on the lift of aerodynamic forces." 53

This

somewhat vague boundary became the basis for organizing the separate Army

and Air Force missile programs in the postwar years.

-

- Most of AAF organizational problems stemmed from its drive for complete

separation from the rest of the Army. The highly advanced and rapidly

changing technology peculiar to the Air Forces and the aircraft industry

presented another and more difficult set of organizational problems. The

main issues concerned the most effective means of co-ordinating the development

and deployment of aircraft along with the training of personnel required

to maintain and operate them. At the end of the war the AAF was still

feeling its way toward solving these problems.54

-

-

- The Operations Division, Army Ground Forces, and Army Air Forces evolved

slowly from existing organizations in the months before Pearl Harbor.

There was no such gradual evolution behind the organization of General

Somervell's command, just the precedent of General Goethals' Purchase,

Storage, and Traffic Division in World War I. What changes had preceded

the creation of the Army Service Forces had been crash actions designed

to meet specific problems. The lagging camp construction program led to

its transfer from an overburdened, overcentralized Quartermaster Corps

to the Corps of Engineers which was faced with a cutback in its own civil

works programs. The lend-lease program led to creation of a new agency,

the Office of the Defense Aid Director. Co-ordination between the Office

of the Under Secretary of War, responsible for mobilizing industrial production,

and G-4, responsible for military supply requirements, became increasingly

difficult as military programs increased in size. The solution provided

by the Marshall reorganization was to combine both activities under General

Somervell's Army Service Forces and relieve G-4 and the

- [90]

- GENERAL SOMERVELL. (Photograph taken in 1945.)

-

- Office of the Under Secretary of War of their operating responsibilities.

This had the virtue, from the military standpoint, of establishing unity

of command over the entire Army supply system in the zone of interior.55

-

- General Somervell was an Army engineer with a well-earned reputation

as an aggressive troubleshooter and administrator who could cut through

red tape and get things done. He had been assigned as head of the Quartermaster

Corps Construction Division in December 1940 to expedite the Army's lagging

camp construction program. He immediately reorganized the division replacing

old branch chiefs with engineers who had worked with him before, Lt. Col.

Edmond H. Leavey, Lt. Col. Wilhelm D. Styer, and Capt. Clinton F. Robinson.

A year later Somervell was promoted to G-4 and thus a logical choice for

the new command. Neither Secretary Stimson nor General Marshall ever appears

to have regretted their selection. Somervell's aggressiveness did stir

up controversy and bitterness

- [91]

- within and outside the Army as General March had done in World War I,

but General Marshall later reflected that if he had to do it all over

again, "I would start looking for another General Somervell the very

first thing I did."

-

- General Marshall also looked to General Somervell as his chief adviser

on supply, treating him as G-4 of the General Staff as well as commanding

general of the ASK Somervell also benefited from the support of Secretary

Stimson and of Harry Hopkins in the White House. On the occasions when

he lost a round in the constant bureaucratic feuding within and outside

the department, he lost because either the Secretary or General Marshall

sided with his opponents.56

-

- The organization of General Somervell's headquarters in the beginning

was a hurried, makeshift grouping of the agencies and personnel assigned

to his command. Integrating their operations required repeated reorganization

of ASF headquarters during the next year and a half. The immediate need

was to link the mobilization and production functions of the Under Secretary's

Office with the military supply requirements and distribution functions

of G-4. General Somervell merged their staffs into one operating agency,

the Directorate of Procurement and Distribution, and attached it to his

own office. At the next level were nine staff divisions responsible for

procurement and distribution operations, training, civilian personnel,

military personnel, fiscal, military requirements, military resources,

and international (lend-lease) . These in turn supervised ASF operating

divisions, the technical and administrative services, and the service

commands.57

-

- Industrial mobilization remained the principal concern of General Somervell

and his staff during the first year. In 1943 emphasis shifted to supply

planning for offensive military

- [92]

- operations overseas. At this point attention focused on the ASF Operations

Division, the agency responsible for logistics planning.

-

- Organizational changes within ASF headquarters reflected this change

in its primary mission. The Directorate of Procurement and Distribution

had become merely one of several staff divisions a year later. The Operations

Division absorbed its distribution functions because supplying overseas

theaters required effective control over and co-ordination of domestic

transportation and supply facilities. In a further reorganization in November

1943, the Operations Division was attached to General Somervell's office

and redesignated the Directorate of Plans and Operations. The former Procurement

Division became its Supply and Materiel Division.. As the link between

logistics, the business of ASF, and strategic planning, the business of

OPD and the JCS, this agency became the most important element in ASF

headquarters. Its chief, Maj. Gen. LeRoy Lutes, and his staff, aggressively

supported by General Somervell, represented the interests of ASF in the

frequently rancorous disputes with OPD over the proper role of logistics

in strategic planning.58

-

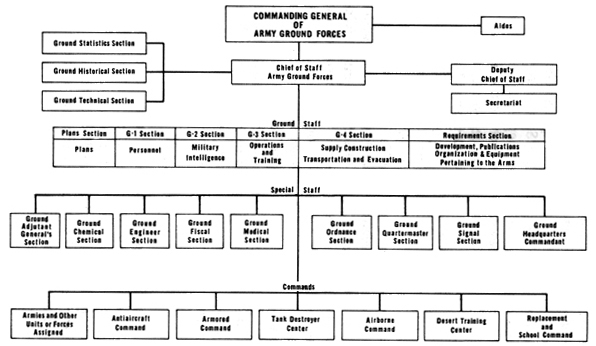

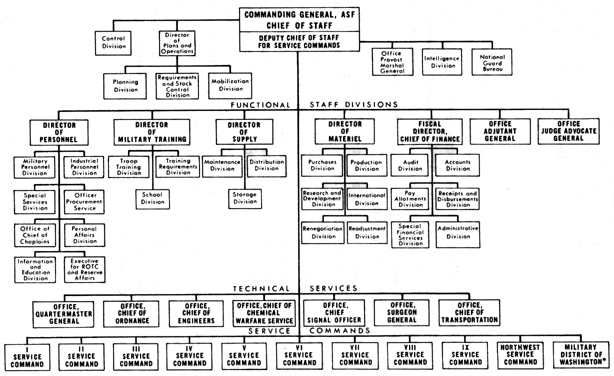

- The organization of ASF headquarters after November 1943 remained relatively

stable. Both the Directorate of Plans and Operations and the Control Division

were attached to General Somervell's office, indicative of their great

importance and influence within ASF headquarters. (Chart 8) Beneath General

Somervell was a Deputy Chief of Staff for Service Commands who relieved

him of this administrative burden. The ASF staff now included seven divisions:

four operating divisions for personnel, military training, supply, and

materiel, and three administrative services, the Fiscal Director (the

Chief of Finance), The Adjutant General's Office, and the Office of the

Judge Advocate General. Like AGF and AAF General Somervell's staff believed

that the attempt to separate staff and operating agencies was

impractical.59

- [93]

- GENERAL LUTES

-

-

- The creation of the Control Division within ASF headquarters was a major

administrative reform within the Army introduced by General Somervell.

Under Maj. Gen. Clinton F. Robinson it performed functions similar to

General Gates' Management Control Division introduced about the same time

in AAF headquarters. Its members for the most part were drawn largely

from civilian management experts rather than military officers who had

had little experience with industrial management.

-

- Its main purpose was to develop and employ industrial management techniques

in the supervision, direction, co-ordination, and control of the disparate

functions and operations for which ASF was responsible. As in the AAF,

there was a Statistical Branch responsible for developing statistical

controls within ASF and for standardizing statistical reporting techniques.

Its Monthly Progress Report, a comprehensive study covering over a dozen

major functions, was one of the principal means by which General Somervell

and his staff reviewed ASF operations. It alerted them to problems as

they developed and helped them maintain a proper balance among the various

elements of the Army's supply system.

-

- The Work Simplification Branch, employing standard in-

- [94]

- ORGANIZATION OF THE ARMY SERVICE FORCES, 15 AUGUST 1944

-

-

- *Under Army Service Forces for Administration and Supply functions.

- Source: Millett: The Organization and Role of Army Service Forces,

p.355.

- [95]

- dustrial work measurement techniques, attempted to organize routine

clerical and industrial operations more efficiently and to simplify supply

and personnel procedures. It was no longer sufficient to justify current

procedures by claiming that "this was the way it had always been

done." OPD and G-2 employed similar techniques in reorganizing their

own paper work.

-

- The Administrative Branch performed functions similar to the AAF Organizational

Planning Division. It studied and developed plans for more effective organization

and administration, and it promoted the use of industrial management techniques

generally throughout the ASF. Its most important function was administrative

troubleshooting. Employing civilian consultants,

it conducted hundreds of special management surveys ranging from manpower

conservation to co-ordinating the allocation of scarce commodities within

the Army under the Controlled Materials Plan.60

-

- The technical services, particularly the Ordnance Department, resented

the Control Division and its efforts to impose management controls alien

to their traditions of bureau autonomy. They regarded its efficiency experts

as a horde of uninformed, meddlesome busybodies. What they resented most

of all was the Control Division's persistent efforts to reorganize the

Army's supply system along functional lines in the manner of the Root

and March reforms. Functionalization as the technical services understood

it meant their ultimate demise as independent operating agencies. Merely

mentioning functionalization was enough to send the Chief of Ordnance,

Maj. Gen. Levin H. Campbell, Jr., into a towering rage. As in the AAF,

opposition stemmed from the fact that management control concepts were

based on the experiences of modern industry rather than the Army. To combat

arms officers, on the other

- [96]

- hand, management controls violated the principle of unity of command.61

-

-

- The main purpose of Army Service Forces was to supply and equip the

Army, including, theoretically, the Air Forces. The Marshall reorganization

made this task difficult because it did not provide for the complete integration

of the Army's supply services as it had the combat arms in Army Ground

Forces. Instead the traditionally autonomous technical services remained

intact, operating the Army's supply system and providing technical services

under the direction of ASF. ASF was thus a holding company, a device industry

generally regarded as inherently clumsy, inefficient, and difficult to

control.

-

- In World War II there were seven technical services. In order of seniority

and tradition they were the Quartermaster Corps, the Corps of Engineers,

the Medical Department, the Ordnance Department, the Signal Corps, the

Chemical Warfare Service, and, after July 1942, the Transportation Corps,

staffed at the top by engineers but created out of the Quartermaster Corps.

Differing widely in organization and purpose, the technical services had

two traditional features in common, their administrative independence

and their dual roles as staff agencies and operating commands.62

-

- As administratively independent agencies they continued to control their

own organizations, procedures, personnel, intelligence, training, supply,

and planning functions. They had their own budgets which accounted for

over one-half the Army's appropriations. As operating agencies they had

installations located in many Congressional districts, their principal

source of political support.

-

- Their dissimilarities were as marked as their similarities. They differed

widely in their often archaic procedures, the result more of historical

accident than of conscious planning.

- [97]

- These differences generated a prodigious amount of red tape, making

it difficult for the department and ASF to control their operations and

for industry to do business with them. ASF and the efficiency experts

of its Control Division hoped to rationalize their structure and operations

along sound businesslike principles.

-

- All the Army technical services in practice combined commodity and service

functions, but in most of them one element was clearly subordinate to

the other. Some were organized along commodity lines like the Ordnance

Department, which was responsible for the design, development, production,

distribution, and maintenance of materiel from the cradle to the grave.

The Corps of Engineers, the Medical Department, and the new Transportation

Corps performed services for the Army and were organized along recognizable