![]()

DARKNESS AND LIGHT

THE INTERWAR YEARS

1865–1898

ith the end of the Civil War, the great volunteer army enlisted

for that struggle was quickly demobilized and the U.S. Army became once again a small regular organization. During the ensuing period the Army faced a variety of problems, some old and some new. These included, besides demobilization, occupation duty in the South, a French threat in Mexico, domestic disturbances, Indian troubles, and, within the Army itself, the old awkward relationship

between the line and the staff departments. Despite a relative isolation

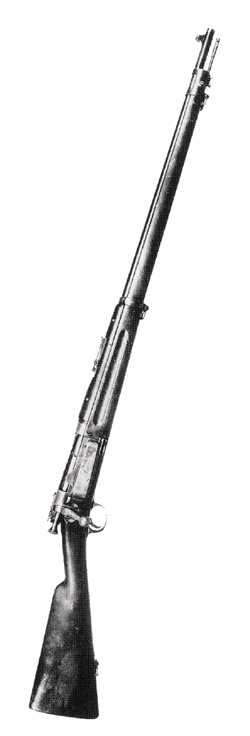

from civilian society during the period 1865–1898, the Army developed professionally, experimented with new equipment of various kinds, and took halting steps toward utilizing the period’s new technology

in weapons. In a period of professional introspection and physical isolation, the Army still contributed to the nation’s civil progress.

ith the end of the Civil War, the great volunteer army enlisted

for that struggle was quickly demobilized and the U.S. Army became once again a small regular organization. During the ensuing period the Army faced a variety of problems, some old and some new. These included, besides demobilization, occupation duty in the South, a French threat in Mexico, domestic disturbances, Indian troubles, and, within the Army itself, the old awkward relationship

between the line and the staff departments. Despite a relative isolation

from civilian society during the period 1865–1898, the Army developed professionally, experimented with new equipment of various kinds, and took halting steps toward utilizing the period’s new technology

in weapons. In a period of professional introspection and physical isolation, the Army still contributed to the nation’s civil progress.

Demobilization, Reorganization,

and the French Threat in Mexico

The military might of the Union was put on display late in May 1865, when Meade’s and Sherman’s armies participated in a grand review in Washington with Sherman’s army alone taking six and one-half hours to pass the reviewing stand on Pennsylvania Avenue. It was a spectacle well calculated to impress on Confederate and foreign leaders alike that only a strong government could field such a powerful force. But even as these troops were preparing for their victory march, the War Department sent Sheridan to command an aggregate force of 80,000 men in the territory west of the Mississippi and south of the Arkansas, of which he put 52,000 in Texas. There Sheridan’s men put muscle behind previ-