![]()

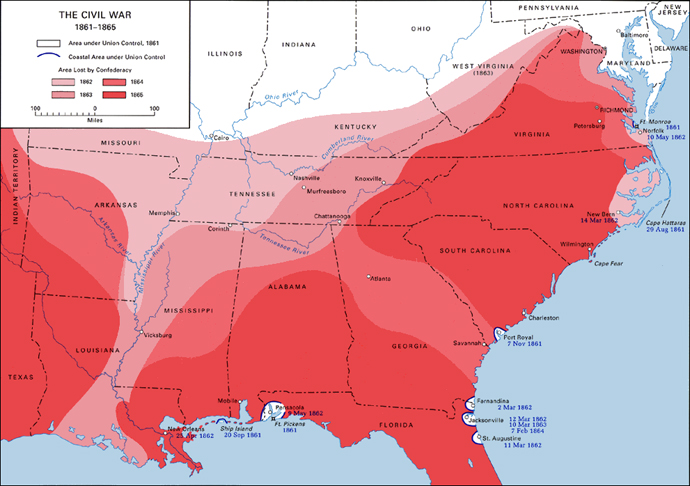

THE CIVIL WAR, 1864–1865

![]() rom Bull Run to Chattanooga, the Union armies had fought their battles without benefit of either a grand strategy or a supreme

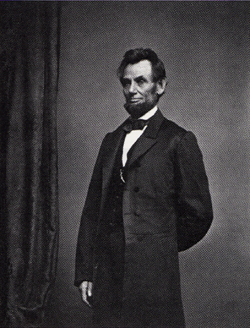

field commander. Even after the great victories of 1863, the situation in 1864 reflected this lack of unity of command. During the final year of the war the people of the North grew restless; and as the election of 1864 approached, many of them advocated a policy of making peace with the Confederacy. President Abraham Lincoln never wavered. Committed to the policy of destroying the armed power of the Confederacy, he sought a general who could pull together all the threads of an emerging strategy and then concentrate the Union armies and their supporting naval power against the secessionists. After Vicksburg

in July 1863, Lincoln leaned more and more toward Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant as the man whose strategic thinking and resolution could lead the Union armies to final victory.

rom Bull Run to Chattanooga, the Union armies had fought their battles without benefit of either a grand strategy or a supreme

field commander. Even after the great victories of 1863, the situation in 1864 reflected this lack of unity of command. During the final year of the war the people of the North grew restless; and as the election of 1864 approached, many of them advocated a policy of making peace with the Confederacy. President Abraham Lincoln never wavered. Committed to the policy of destroying the armed power of the Confederacy, he sought a general who could pull together all the threads of an emerging strategy and then concentrate the Union armies and their supporting naval power against the secessionists. After Vicksburg

in July 1863, Lincoln leaned more and more toward Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant as the man whose strategic thinking and resolution could lead the Union armies to final victory.

Acting largely as his own General in Chief, although Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck had been given that title after George B. McClellan’s removal in early 1862, Mr. Lincoln had watched the Confederates fight from one victory to another inside their cockpit of northern Virginia. In the Western Theater, Union armies, often operating independently of one another, had scored great victories at key terrain points. But their hold on the communications base at Nashville was always in jeopardy as long as the elusive armies of the Confederacy could escape to fight another day at another key point. The twin, uncoordinated victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, 900 miles apart, only pointed out the North’s need for an overall strategic plan and a general who could carry it out.

Having cleared the Mississippi River, Grant wrote to Halleck and the President in the late summer of 1863 about the opportunities now open to his army. Grant first called for the consolidation of the autonomous

western departments and the coordination of their individual