![]()

THE MEXICAN WAR

AND AFTER

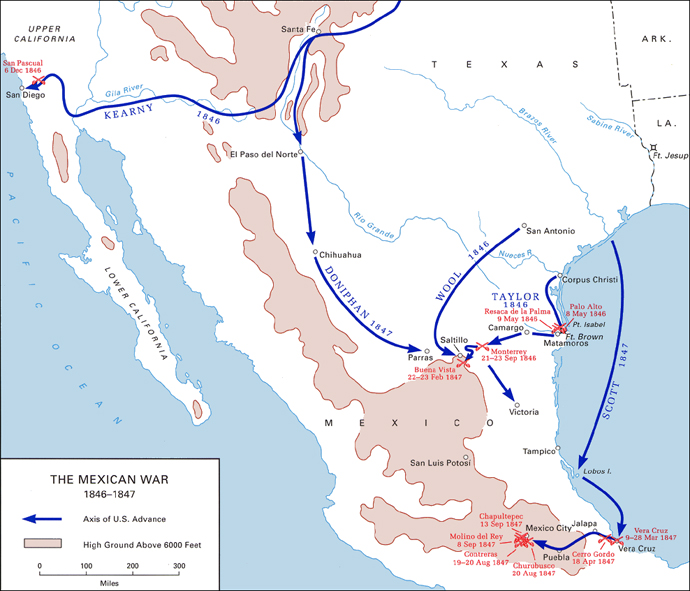

eceiving by the new telegraph the news that James K. Polk had been elected to the Presidency in November 1844, President John Tyler interpreted the verdict as a mandate from the people for the annexation of Texas, since Polk had come out strongly in favor of annexation. On March 1, 1845, Congress jointly resolved to admit Texas into the Union and the Mexican Government promptly broke off diplomatic relations. President Polk continued to hope that he could settle by negotiation Mexico’s claim to Texas and acquire Upper California

by purchase as well. In mid-June, nevertheless, anticipating Texas’ Fourth of July acceptance of annexation, he ordered Bvt. Brig. Gen. Zachary Taylor to move his forces from Fort Jesup on the Louisiana border to a point "on or near" the Rio Grande to repel any invasion from Mexico.

eceiving by the new telegraph the news that James K. Polk had been elected to the Presidency in November 1844, President John Tyler interpreted the verdict as a mandate from the people for the annexation of Texas, since Polk had come out strongly in favor of annexation. On March 1, 1845, Congress jointly resolved to admit Texas into the Union and the Mexican Government promptly broke off diplomatic relations. President Polk continued to hope that he could settle by negotiation Mexico’s claim to Texas and acquire Upper California

by purchase as well. In mid-June, nevertheless, anticipating Texas’ Fourth of July acceptance of annexation, he ordered Bvt. Brig. Gen. Zachary Taylor to move his forces from Fort Jesup on the Louisiana border to a point "on or near" the Rio Grande to repel any invasion from Mexico.

The Period of Watchful Waiting

General Taylor selected a wide sandy plain at the mouth of the Nueces River near the hamlet of Corpus Christi and beginning July 23 sent most of his 1,500-man force by steamboat from New Orleans. Only his dragoons moved overland, via San Antonio. By mid-October, as shipments of regulars continued to come in from all over the country, his forces had swollen to nearly 4,000, including some volunteers from New Orleans. This force constituted nearly 50 percent of the 7,365-strong Regular Army. A company of Texas Rangers served as the eyes and ears of the Army. For the next six months tactical drilling, horse breaking, and parades, interspersed with boredom and dissipation, went on at the big camp on the Nueces. Then in February Taylor received orders from Washington to advance into disputed territory to the Rio Grande. Negotiations with the Mexican government had broken down.