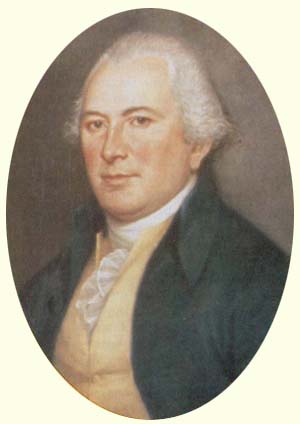

Oil, by Charles Willson Peale (1784); Independence National Historical Park.

THOMAS MIFFLIN

Pennsylvania

Birth: 10 January 1744, at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Death: 20 January 1800, at Lancaster, Pennsylvania

Interment: Trinity Lutheran Church Cemetery, Lancaster, Pennsylvania

Oil, by Charles Willson Peale (1784); Independence National Historical Park.

Thomas Mifflin, who represented Pennsylvania at the Constitutional Convention, seemed full of contradictions. Although he chose to become a businessman and twice served as the chief logistical officer of the Revolutionary armies, he never mastered his personal finances. A Quaker with strong pacifist beliefs, he helped organize Pennsylvania's military forces at the outset of the Revolution and rose to the rank of major general in the Continental Army. Despite his generally judicious deportment, contemporaries noted his "warm temperament" that led to frequent quarrels, including one with George Washington that had national consequences.

Throughout the twists and turns of a checkered career Mifflin remained true to ideas formulated in his youth. Believing mankind an imperfect species composed of weak and selfish individuals, he placed his trust on the collective judgment of the citizenry. As he noted in his schoolbooks, "There can be no Right to Power, except what is either founded upon, or speedily obtains the hearty Consent of the Body of the People." Mifflin's service—during the Revolution, in the Constitutional Convention, and, more importantly, as governor during the time when the federal partnership between the states and the national government was being worked out—can only be understood in the context of his commitment to these basic principles and his impatience with those who failed to live up to them.

The Patriot

Mifflin was among the fourth generation of his family to live in Philadelphia, where his Quaker forebears had attained high rank. His father served as a city alderman, on the Governor's Council, and as a trustee of the College of Philadelphia (today's University of Pennsylvania). Mifflin attended local grammar schools and graduated in 1760 from the College. Following in his father's footsteps, he then apprenticed himself to an important local merchant, completing his training with a year-long trip to Europe to gain a better insight into markets and trading patterns. In 1765 he formed a partnership in the import and export business with a younger brother.

Mifflin married a distant cousin, and the young couple—witty, intelligent, and wealthy—soon became an ornament in Philadelphia's highest social circles. In 1768 Mifflin joined the American Philosophical Society, serving for two years as its secretary. Membership in other fraternal and charitable organizations soon followed. Associations formed in this manner quickly brought young Mifflin to the attention of Pennsylvania's most important politicians, and led to his first venture into politics. In 1771 he won election as a city warden, and a year later he began the first of four consecutive terms in the colonial legislature.

Mifflin's business experiences colored his political ideas. He was particularly concerned with Parliament's taxation policy and as early as 1765 was speaking out against London's attempt to levy taxes on the colonies. A summer vacation in New England in 1773 brought him in contact with Samuel Adams and other Patriot leaders in Massachusetts, who channeled his thoughts toward open resistance. Parliament's passage of the Coercive Acts in 1774, designed to punish Boston's merchant community for the Tea Party, provoked a storm of protest in Philadelphia. Merchants as well as the common workers who depended on the port's trade for their jobs recognized that punitive acts against one city could be repeated against another. Mifflin helped to organize the town meetings that led to a call for a conference of all the colonies to prepare a unified position.

In the summer of 1774 Mifflin was elected by the legislature to the First Continental Congress. There, his work in the committee that drafted the Continental Association, an organized boycott of English goods adopted by Congress, spread his reputation across America. It also led to his election to the Second Continental Congress, which convened in Philadelphia in the aftermath of the fighting at Lexington and Concord.

The Soldier

Mifflin was prepared to defend his views under arms, and he played a major role in the creation of Philadelphia's military forces. Since the colony lacked a militia, its Patriots turned to volunteers. John Dickinson and Mifflin resurrected the so-called Associators (a volunteer force in the colonial wars, perpetuated by today's 111th Infantry, Pennsylvania Army National Guard). Despite a lack of previous military experience, Mifflin was elected senior major in the city's 3d Battalion, a commission that led to his expulsion from his Quaker church.

Mifflin's service in the Second Continental Congress proved short-lived. When Congress created the Continental Army as the national armed force on 14 June 1775, he resigned, along with George Washington, Philip Schuyler, and others, to go on active duty with the regulars. Washington, the Commander in Chief, selected Mifflin, now a major, to serve as one of his aides, but Mifflin's talents and mercantile background led almost immediately to a more challenging assignment. In August, Washington appointed him Quartermaster General of the Continental Army. Washington believed that Mifflin's personal integrity would protect the Army from the fraud and corruption that too often characterized eighteenth-century procurement efforts. Mifflin, in fact, never used his position for personal profit, but rather struggled to eliminate those abuses that did exist in the supply system.

As the Army grew, so did Mifflin's responsibilities. He arranged the transportation required to place heavy artillery on Dorchester Heights, a tactical move that ended the siege of Boston. He also managed the complex logistics of moving troops to meet a British thrust at New York City. Promoted to brigadier general in recognition of his service, Mifflin nevertheless increasingly longed for a field command. In 1776 he persuaded Washington and Congress to transfer him to the infantry. Mifflin led a brigade of Pennsylvania continentals during the early part of the New York City campaign, covering Washington's difficult nighttime evacuation of Brooklyn. Troubles in the Quartermaster's Department demanded his return to his old assignment shortly afterwards, a move which bitterly disappointed him. He also brooded over Nathanael Greene's emergence as Washington's principal adviser, a role which Mifflin coveted.

Mifflin's last military action came during the Trenton-Princeton campaign. As the Army's position in northern New Jersey started to crumble in late November 1776, Washington sent him to Philadelphia to lay the groundwork for a restoration of American fortunes. Mifflin played a vital, though often overlooked, role in mobilizing the Associators to reinforce the continentals and in orchestrating the complex resupply of the tattered American forces once they reached safety on the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware River. These measures gave Washington the resources to counterattack. Mifflin saw action with the Associators at Princeton. His service in the campaign resulted in his promotion to major general.

Mifflin tried to cope with the massive logistical workload caused by Congress' decision in 1777 to expand the Continental Army. Congress also approved a new organization of the Quartermaster's Department, but Mifflin had not fully implemented the reforms and changes before Philadelphia fell. Dispirited by the loss of his home and suffering from poor health, Mifflin now attempted to resign. He also openly criticized Greene's advice to Washington. These ill-timed actions created a perception among the staff at Valley Forge that Mifflin was no longer loyal to Washington.

The feuding among Washington's staff and a debate in Congress over war policy led to the so-called Conway Cabal. A strong faction in Congress insisted that success in the Revolution could come only through heavy reliance on the militia. Washington and most of the Army's leaders believed that victory depended on perfecting the training and organization of the continentals so that they could best the British at traditional European warfare. This debate came to a head during the winter of 1777-78, and centered around the reorganization of the Board of War, Congress' administrative arm for dealing with the Army. Mifflin was appointed to the Board because of his technical expertise, but his political ties embroiled him in an unsuccessful effort to use the Board to dismiss Washington. This incident ended Mifflin's influence in military affairs and brought about his own resignation in 1779.

The Statesman

Mifflin lost little time in resuming his political career. While still on active duty in late 1778 he won reelection to the state legislature. In 1780 Pennsylvania again sent him to the Continental Congress, and that body elected him its president in 1783. In an ironic moment, "President" Mifflin accepted Washington's formal resignation as Commander in Chief. He also presided over the ratification of the Treaty of Paris, which ended the Revolution. Mifflin returned to the state legislature in 1784, where he served as speaker. In 1788 he began the first of two one-year terms as Pennsylvania's president of council, or governor.

Although Mifflin's fundamental view of government changed little during these years of intense political activity, his war experiences made him more sensitive to the need for order and control. As Quartermaster General, he had witnessed firsthand the weakness of Congress in dealing with feuding state governments over vitally needed supplies, and he concluded that it was impractical to try to govern through a loose confederation. Pennsylvania's constitution, adopted in 1776, very narrowly defined the powers conceded to Congress, and during the next decade Mifflin emerged as one of the leaders calling for changes in those limitations in order to strike a balanced apportionment of political power between the states and the national government.

Such a system was clearly impossible under the Articles of Confederation, and Mifflin had the opportunity to press his arguments when he represented Pennsylvania at the Constitutional Convention in 1787. Although his dedication to Federalist principles never wavered during the deliberations in Philadelphia, his greatest service to the Constitution came later when, as the nationalists' primary tactician, he helped convince his fellow Pennsylvanians to ratify it.

Elected governor under the new state constitution in 1790, Mifflin served for nine years, a period highlighted by his constant effort to minimize partisan politics in order to build a consensus. Although disagreeing with the federal government's position on several issues, Mifflin fully supported Washington's efforts to maintain the national government's primacy. He used militia, for example, to control French privateers who were trying to use Philadelphia as a base in violation of American neutrality. He also commanded Pennsylvania's contingent called out in 1794 to deal with the so-called Whiskey Rebellion, even though he was in sympathy with the economic plight of the aroused western farmers.

In these incidents Mifflin regarded the principle of the common good as more important than transitory issues or local concerns. This same sense of nationalism led him to urge the national government to adopt policies designed to strengthen the country both economically and politically. He led a drive for internal improvements to open the west to eastern ports. He prodded the government to promote "National felicity and opulance ... by encouraging industry, disseminating knowledge, and raising our social compact upon the permanent foundations of liberty and virtue." In his own state he devised a financial system to fund such programs. He also took very seriously his role as commander of the state militia, devoting considerable time to its training so that it would be able to reinforce the Regular Army.

Mifflin retired in 1799, his health debilitated and his personal finances in disarray. In a gesture both apt and kind, the commander of the Philadelphia militia (perpetuated by today's 111th Infantry and 103d Engineer Battalion, Pennsylvania Army National Guard) resigned so that the new governor might commission Mifflin as the major general commanding the states senior contingent. Voters also returned him one more time to the state legislature. He died during the session and was buried at state expense, since his estate was too small to cover funeral costs.

[109-111]