|

CHAPTER III From the Tropics to the Arctic Having concentrated on its weather duties for the past twenty years, the Signal Corps had fallen behind in the field of military communications. Although the Army still used flags and torches to convey information, the rapidly developing technology of the late nineteenth century carried communications into the electrical age. The growing sense of professionalism both in society at large and within the Army, along with the concomitant specialization of functions, finally gave the Signal Corps the sense of mission and identification for which it had long been striving. The emergence of the United States as a great power in the wake of the War with Spain found the Signal Corps providing communications around the globe. Organization, Training, and Operations, 1891-1898 The act transferring the weather service outlined the functions assigned to the Signal Corps in some detail. In addition to performing all military signal duties and retaining charge of the "books, papers, and devices connected therewith," the branch's responsibilities now included:

Finally, the legislation specified that the Corps' operations would be "confined to strictly military matters." While Congress thus defined the Corps' mission more explicitly than in previous legislation, it still left a considerable area open to interpretation under the category of "other duties usually pertaining to military signaling." The legislation set the Signal Corps' strength at one brigadier general, one major, four captains, four first lieutenants, and fifty sergeants. Upon the transfer of the weather duties, the Signal Corps turned its attention to the rather sorry state of its military signaling apparatus. During the twenty years that the branch had operated the weather service, it had lost its technical predominance in the signaling field. Chief Signal Officer Greely described the telegraph train as "antiquated," and the Corps' tiny appropriation of $22,500 (excluding personnel costs) for fiscal year 1892 barely covered regular expenses, let alone extensive research and development of new equipment.2 [81] Despite the lack of research funds, the ingenuity of signal officers frequently led to the creation of new items. In 1892, for example, Capt. Charles E. Kilbourne developed the outpost cable cart. A wheeled vehicle weighing slightly over fifty pounds, it included an automatic spooling device that enabled a man to lay two miles of insulated double-conductor telephone cable. Because the existing portable field telephone kit contained only one-third mile of cable, Kilbourne's invention became valuable when longer lines were needed. The versatile cart could also be adapted to other uses-for instance, to carry wounded soldiers from the field. Two years later, Capt. James Allen developed a method of "duplexing" whereby both telegraphic and telephonic messages could be sent simultaneously over the same line, greatly increasing its efficiency.3 The United States Army had to catch up with its European counterparts, most of whom had by now successfully employed field telegraphy. The British Army, in particular, made extensive use of field lines while fighting a series of colonial wars in Africa.4 After the long period of neglect, the telegraph train began to receive some attention. To provide more opportunities for practice, Greely sent trains to Fort Grant, Arizona; Fort Sam Houston, Texas; and the Presidio of San Francisco to supplement those at the Infantry and Cavalry School at Fort Leavenworth and the Cavalry and Light Artillery School at Fort Riley. In May 1892, "for the first time since the war of the rebellion," the Signal Corps constructed a field telegraph line. At the request of the International Boundary Commission, the Corps ran a line from Separ, New Mexico, to the monument marking the international boundary between Mexico and the United States. Four Signal Corps sergeants, assisted by Company D, 24th Infantry, built the 35-mile line in twenty-five working hours, despite difficult working conditions. The Corps used the line to transmit chronometric signals between the monument and the observatory at El Paso, Texas, 100 miles to the east, for the purpose of determining the monument's exact longitude.5 A more urgent need for a field telegraph arose later that year when the possibility of border trouble loomed with Mexico. At the insistence of the Mexican government, the Army was called upon to stop a band of Mexican revolutionaries headed by Catarino Garza that based its operations in southern Texas. In response to rumors of the band's activities, Army units rushed back and forth across the countryside in pursuit of Garza. As might be expected, communications in this part of the country were poor. Because Congress did not appropriate sufficient funds to build permanent lines, the Corps drew on its available stock of field line around the country to build a temporary connection of nearly 75 miles between Fort McIntosh, Texas (at Laredo), and Lopena, Texas.6 The signal students from Fort Riley constructed the Texas line, only one of several occasions on which they demonstrated the signal skills they had learned. They provided communications for the dedication ceremonies of the World's Columbian Exposition held in Chicago in October 1892, and then they returned for more serious duty during the violent strike against the Pullman Sleeping Car Company in July 1894. Against the wishes of Illinois Governor John Peter [82] Atgeld, President Grover Cleveland called out troops to expedite movement of the mail and to protect interstate commerce. Maj. Gen. Nelson A. Miles, commander of the 2,000 federal troops sent to Chicago, requested the services of signal soldiers. Under Capt. James Allen, the signal troops (1st Lt. Joseph E. Maxfield and twelve sergeants) established a system of visual, telegraph, and telephone lines that connected Miles with his subordinate commanders. The signal troops also operated lines in conjunction with the commercial telephone and telegraph companies.7 In addition to its temporary field duties, the Signal Corps continued to operate permanent telegraph lines. According to the terms of the agreement to transfer the weather service, the Corps relinquished control over its 600 miles of sea coast telegraph lines, which thereupon became the property of the Department of Agriculture. The Corps retained, however, the lines that connected military posts, totaling just over 1,000 miles in length. Signal Corps sergeants operated the more important lines, such as those at departmental headquarters, and civilian operators worked the rest.8 The Corps discontinued its lines where no longer needed, but it also occasionally built new ones. When appropriations became available, the Corps completed, late in 1893, a permanent line between Fort Ringgold and Fort McIntosh in Texas to replace the temporary flying line. Maintenance proved difficult, however, due to a tendency of some of the local inhabitants to damage it "by pistol practice on the insulators and lariat practice on the poles." The chief signal officer reported in 1894 that the situation had improved "through the judicious influence of the more intelligent citizens."9 While coping with such circumstances, the Signal Corps constantly sought more efficient methods to perform line repair and maintenance. In keeping with the bicycle craze then rolling across the nation, the Corps found its own uses for the velocipede, as it was then called. Bicycles provided a faster and more economical means for making repairs. In the time it took to secure a horse and wagon, a linesman could jump on his bicycle, repair the line, and return to his station. The Corps also began adapting the bicycle to lay and take up wire. The replacement of wooden with iron poles also lessened the damage caused by deterioration or fire.10 In addition to the frontier land lines, the Signal Corps had retained control of the cables in San Francisco Harbor that linked its fortifications to the mainland. Unfortunately, the weather and ships' anchors conspired to render them inoperative much of the time. The Corps lacked the funds to make substantial repairs or to build new cables, and Greely's requests for additional funds went unanswered. Cable connections were also needed in New York and Boston, harbors that were vital to the nation's defense. These difficulties spurred the Signal Corps' development of wireless communication.11 The Signal Corps' involvement in coastal defense went beyond its control of electrical cables in major harbors. In addition to improvements in communication methods, the technological achievements of the post Civil War era revolutionized [83] coast artillery through the introduction of such items as steel guns, more powerful propellants, and high explosive shells. These advances rendered obsolete the existing coastal fortifications, which dated from the Civil War or earlier. Concern over the poor condition of the nation's coastal defenses led to the assembly of the Endicott Board by President Cleveland in 1885. The board conducted an extensive review of coastal fortifications and developed an ambitious improvement program. Congress responded by creating the Board of Ordnance and Fortification in 1888 to supervise projects relating to coast defense. The Signal Corps became involved by installing electrical communication systems for fire direction that made more precise fire control possible. Prior to this time aiming had been done by each individual gun. Now several sighting stations took optical bearings of the moving target and telephoned the information to a central plotting room where targeting positions were determined. The results were then communicated to the gun emplacements to direct their fire. The Signal Corps had only begun the installation program when war broke out with Spain in 1898, but work would resume in the postwar period.12 The Board of Ordnance and Fortification did not concern itself solely with matters of coast defense. While the enabling legislation gave it responsibility to "make all needful and proper purchases, investigations, experiments, and tests" of guns and other items of ordnance, it also could investigate "other implements and engines of war." This broad mandate made the board, in effect, a vehicle to support research and development. The board's grant of $25,000 to Samuel P. Langley, secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, in 1898 for building an aerodrome marked an important milestone in the evolution of heavier-than-air flight. Greely had urged the secretary of war to support Langley's efforts, and the board made the chief signal officer responsible for the expenditure of this money and a subsequent grant of equal amount. (Greely later called his work with Langley "the most important peace duty I ever performed.")13 Besides its association with Langley, the Signal Corps became directly involved in aeronautical matters as it expanded its communications mission. 1st Lt. Richard E. Thompson, in charge of the Division of Military Signaling, remarked in his report to Greely in 1889 that several European countries were using captive balloons for reconnaissance and had devised balloon trains.14 The United States Army had not used captive balloons for observation since the work of Thaddeus Lowe and others during the Civil War. Greely, noting the success of the French with the use of captive balloons in maneuvers, included an estimate of $11,000 for the purchase and construction of a balloon train in his budget request to Congress for the fiscal year ending 30 June 1893.15 The balloon would accompany each telegraph train and be used as a portable observation platform to gather information on topography, the disposition and movement of troops, and the like. Communication between the train and the balloon would be carried through the anchor rope, which contained insulated copper wires and doubled as a telephone cable. (During the Civil War Lowe had communicated with the ground via telegraph.)16 [84] THE SIGNAL CORPS' BALLOON AT THE WORLD'S COLUMBIAN EXPOSITION IN CHICAGO, 1893 When Congress refused to appropriate funds for balloons, Greely sought and received approval from the secretary of war and the commanding general of the Army to use part of the Signal Corps' regular appropriation for this purpose. The secretary of war assigned responsibility for obtaining a balloon to 1st Lt. William A. Glassford and released him from his duties with the Weather Bureau. In the summer of 1892 Glassford traveled to Paris, the center of European ballooning activity, and purchased a balloon from a French manufacturer for $1,970.17 Christened the General Myer in honor of the first chief signal officer, the balloon became part of the Corps' exhibit at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, where it made demonstration ascensions under the supervision of Thompson, now a captain. At a conference on aerial navigation held in conjunction with the fair, the delegates discussed the newly realized possibility of aerial warfare. When the fair closed in the fall of 1893, the chief signal officer sent the balloon to Fort Riley for use by the signal detachment stationed there.18 The Signal Corps' balloon was spherical in shape and made of goldbeater's skin, a polite term for a material made from the intestines of cattle. The balloon was inflated with hydrogen that was usually generated from sulfuric acid and iron filings, but this process was a slow one. For service in the field, steel cylinders of compressed hydrogen provided a portable means of gas supply. The Myer needed [85] 135 such cylinders per inflation. The balloon train would carry these cylinders in 3 wagons, each loaded with 45 tubes weighing about 70 pounds each. A fourth wagon hauled the balloon and its additional accouterments. During the Civil War Lowe had used portable gas generators for his balloons, but the Signal Corps had difficulty in securing suitable equipment.19 The Corps' initial aeronautical attempts proved somewhat disappointing. During the Pullman strike in Chicago, the commander of the Department of Missouri, General Miles, requested the use of the General Myer, but improving conditions in the city made its deployment unnecessary.20 When the signal detachment returned to Fort Riley from duty in Chicago, it found the Myer suffering from the lack of maintenance.21 The men nevertheless resumed their aerial operations, but with limited results. Difficulty with gas generation posed a chronic problem, and erratic weather conditions, especially sudden high winds, aborted many of the ascension attempts. With the encouragement of Captain Glassford, now signal officer of the Department of the Colorado, the balloon detachment transferred in 1894 to Fort Logan, near Denver, Colorado, where conditions were better suited to aeronautics. However, when the Myer arrived from Fort Riley, it had deteriorated to the point that it burst while being inflated. Unable to afford a new French balloon, the Signal Corps agreed to purchase a homemade silken sphere from the aeronaut Ivy Baldwin, who had enlisted in the Corps to assist with ballooning. Meanwhile, a balloon shed, a gas generating plant, and a compressor were made ready. By 1897 the balloon detachment was able to resume its operations under somewhat improved conditions, but the Corps' limited funds kept experimentation to a minimum.22 Despite his initiatives in several fields, Greely did not meet with complete success in his efforts to obtain new duties for his branch. During 1892 he engaged in a bureaucratic struggle for control of the Military Information Division, which had been created within The Adjutant General's Office in 1885. Greely claimed that this function fell within the Signal Corps' auspices, as outlined in the legislation of 1890. The chief signal officer lost this fight, however, and the military information function remained with the adjutant general.23 In 1894 the Signal Corps did acquire another new responsibility: supervision of the War Department library. In addition to books, the library's holdings included the photographs taken by Mathew Brady during the Civil War. The War Department had purchased the pictures in 1875 when financial difficulties had forced Brady to sell them. In order to preserve this precious resource, Greely discontinued loaning out the negatives, a practice that had resulted in considerable loss and damage. He also instituted a cataloging project to correctly identify the remaining photographs.24 While Greely solidified the Signal Corps' position within the Regular Army, the state militia also provided a fertile ground for the growth of signaling in the closing decades of the nineteenth century. The labor unrest of the 1870s had stimulated a revival of interest in the organized militia or National Guard, and between 1881 and 1892 every state revised its military code to provide for an [86] organized militia.25 As early as the autumn of 1882 the state of Massachusetts detailed men to signal duty during the annual brigade encampment. A Regular Army signalman attended the encampment to aid in signal instruction and to take weather observations.26 In fact, signal units were organized in the militia before their counterparts existed in the Regular Army. New York became one of the first states to organize signal units in 1885. The 101st Signal Battalion of the New York Army National Guard traces its lineage to those early units. Another signal unit with a long history, the 133d Signal Battalion of the Illinois Army National Guard, was originally organized as a signal company in 1897. In that year nearly a dozen states reported having a signal corps within their militia structure. Several other states reported some form of signal organization at brigade, regimental, or battalion level. In the District of Columbia an engineer company performed signal duties.27 In 1892 Andrew Carnegie's attempt to break the iron and steel workers' union at his plant in Homestead, Pennsylvania, resulted in a violent strike, and Governor William Stone called up the militia to restore order. Although the Pennsylvania National Guard had no organized signal corps per se, several of its companies had signaling experience, and Company H, 12th Pennsylvania Infantry, provided communications during the riots. As Assistant Adjutant General Maj. William J. Volkmar reported:

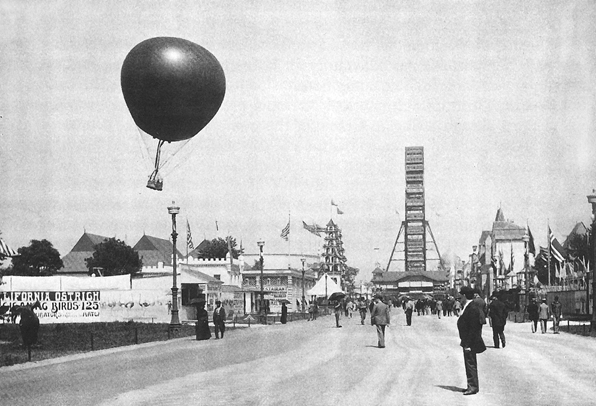

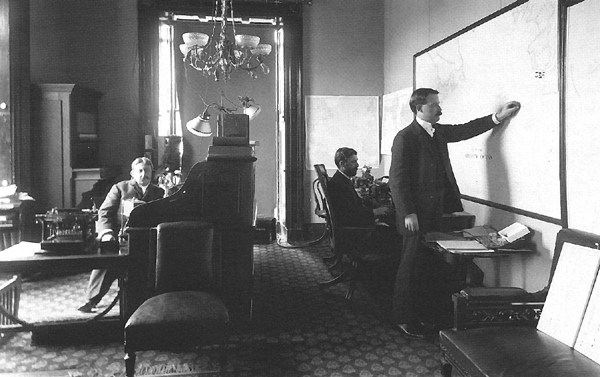

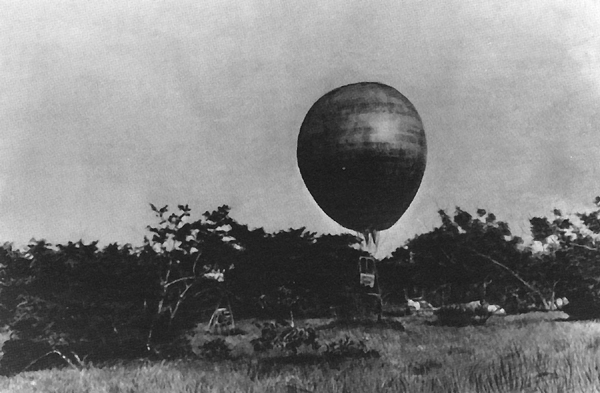

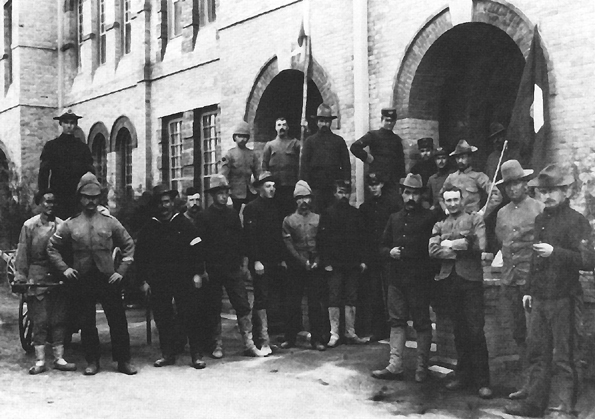

One of the projects delayed by the strike was work on the armored battleship Maine, then under construction at the Carnegie mills.29 While state forces made progress, the federal government hesitated. Throughout the 1890s Greely expressed concern about the Army's shortage of trained signalmen. As in the past, the system of instruction at the various posts had not proved very successful. The departments were not devoting enough time to signal training for the men to become skilled. Moreover, the line soldiers who were detailed for signal training would probably be needed by their own companies in the event of combat. Although the Corps had been able to provide sufficient numbers of signalmen during the Pullman riot in Chicago, Greely worried that, in the event of a more serious emergency, there would not be enough experienced men available. Therefore, in both 1894 and 1895 he recommended to the secretary of war that fifty privates be added to the branch. In 1896 he increased his request to four companies of fifty men each.30 But his pleas for additional personnel went unanswered. In addition, two of the Corps' allotment of ten officers served on detached duty until the outbreak of the War with Spain. Maj. H. H. C. [87] Dunwoody (promoted to lieutenant colonel in 1897) remained with the Weather Bureau while Capt. George E Scriven served as the military attaché to Rome. Thus, as the United States moved toward its first conflict on foreign soil since the Mexican War, the Signal Corps had available only eight officers and fifty men to provide the necessary communications. A new national commitment would be required to create an army that was ready for war. The sinking of the Maine in Havana harbor in February 1898 precipitated the crisis. When Spain failed to respond to diplomatic pressure, Congress declared war in April of that year. While it proved to be a "little" war, lasting only a few months, the nation emerged from the conflict as a world power. The war also provided a glimpse of the impact that the technological innovations of the era would have on the nature of warfare. Before the fighting was over, the Signal Corps demonstrated that it could link the Army electrically with its commander in chief thousands of miles away. In the beginning the United States Army and the Signal Corps in particular found themselves unprepared for war. Since the massive demobilization after the Civil War, Congress had limited the Army's strength to an average of 26,000 officers and men; in April 1898 it stood at slightly over 28,000.31 The tiny Signal Corps of eight officers and fifty enlisted men comprised a minuscule percentage of this total. Moreover, the Corps counted just $800 in its war chest. Greely had to obtain additional money from Congress, amounting to $609,000 through December 1898.32 To provide the needed manpower for wartime operations, Congress authorized the formation of a Volunteer Signal Corps which, as in the Civil War, was authorized only "for service during the existing war." Congress set its strength at 1 colonel, 1 lieutenant colonel, 1 major as disbursing officer, and other officers as required, not to exceed 1 major for each army corps. Each division was allotted 2 captains, 2 first lieutenants, and 2 second lieutenants, as well as an enlisted force of 15 sergeants, 10 corporals, and 30 privates. Significantly, the legislation specified that two-thirds of the officers below the rank of major and the same proportion of enlisted men be skilled electricians or telegraph operators.33 The regular signal establishment provided the nucleus around which the wartime corps was formed. Dunwoody, relieved from his weather duties, became the colonel of the Volunteer Signal Corps, and James Allen received the lieutenant colonelcy.34 The remaining junior officers became field officers in the volunteer organization. Most of the enlisted force also joined the volunteers. To free signal soldiers for field service, civilians replaced the signal sergeants on duty with the military telegraph lines. To quickly obtain skilled men to fill its expanded ranks, the Signal Corps recruited men from private business, particularly the electrical and telegraph industries. The signal units in the National Guard also provided a significant source of experienced personnel as well as a supply of [88] much-needed equipment.35 Upon enlistment, these men reported to Washington Barracks, D.C., for training in signal techniques and military drill. There they were organized into companies of approximately four officers and fifty-five men each. Despite the wording of the legislation setting up the volunteer corps, the companies were not assigned to divisions, but were consolidated at corps headquarters (generally three to a corps) for distribution as the commanding general saw fit.36 Due to the short duration of the conflict, most of these companies did not serve overseas but instead performed communication duties at the various mobilization camps. Upon the declaration of war on 25 April, President William McKinley ordered Chief Signal Officer Greely to take possession of the nation's telegraph system, both cable and land lines. The Signal Corps particularly exercised its jurisdiction over those lines with termini in New York City, Key West, and Tampa. The commercial companies, including those owned by foreign firms, censored themselves under the supervision of a signal officer. The censors prohibited the transmission of information regarding military movements and of any messages between Spain and its colonies except for personal and commercial messages in plain text that were deemed not to contain sensitive information. The Corps also disallowed messages in cipher to foreign nations except those between the diplomatic and consular representatives of neutral governments.37 Through its perusal of telegraphic traffic the Signal Corps derived much valuable information. One of the most critical items concerned the arrival in Santiago harbor on 19 May of a Spanish squadron under Admiral Pascual Cervera. Americans feared an attack on the East Coast by Cervera's ships. The Navy had last sighted the squadron on 13 May west of Martinique, and three days later the American consul at Curagao reported Cervera's arrival there. Then Cervera disappeared from sight once more, his destination unknown. On the morning of the 19th, James Allen, who was monitoring telegraphic traffic at Key West, received news of the squadron's entrance into Santiago from a special agent in the Havana telegraph office. Allen, then a captain, immediately sent the news on to Greely, who relayed it in person to McKinley. The Navy Department, while unable to confirm Cervera's arrival for another ten days, took the Signal Corps' report seriously and initiated action to close the port of Santiago.38 Shortly before the declaration of war, the Navy Department had dispatched a squadron under Admiral William T. Sampson to blockade the Cuban coast. On 19 May, the same day the Signal Corps received its report of Cervera's arrival in Santiago, a squadron commanded by Commodore Winfield Scott Schley (Greely's Arctic rescuer) left for Cienfuegos, on the southern coast of Cuba, thought to be Cervera's likely destination. Even after receiving orders from Sampson on 23 May indicating that Cervera was probably at Santiago and directing him to proceed to that port, Schley remained for several days at Cienfuegos in the mistaken belief that Cervera was anchored there. Meanwhile, Sampson's squadron moved to intercept Cervera should he attempt to enter Havana. Schley finally arrived off Santiago on 26 May, but left almost immediately for Key West without reconnoi- [89] tering the harbor. After more delay and a profusion of orders from Sampson and Secretary of the Navy John D. Long, Schley returned to Santiago on 28 May to blockade the port. The following day one of his ships sighted a Spanish man-ofwar near the harbor entrance, putting the speculation about Cervera's location to an end at last. With this confirmation of Allen's report, the Navy Department requested that the Army send troops to Santiago to help destroy the Spanish squadron. The War Department, which had previously focused its attention on Havana, now hastily planned a campaign against Santiago.39 Among the Signal Corps' first operations was the outfitting of an expedition to cut the underwater telegraph cables that connected Cuba with Spain and to establish cable communication between American forces arriving in Cuba and the United States. The Corps, however, had no ships in its inventory, and the Navy had purchased all the submarine cable available in the United States. With the help of officials of the Western Union and Mexican Telegraph companies, Greely chartered the Norwegian ship Adria, outfitted it, and secured a small amount of cable. The Mexican Telegraph Company provided the necessary cable gear. When ready, the Adria sailed from New York to Key West where it came under the command of Allen, by now a lieutenant colonel. A major problem arose, however, when the captain and crew of the private vessel balked at the hazardous nature of the mission. Eventually they agreed to sail, but the experienced cable handlers hired for the job refused. To replace these men, Allen received three Signal Corps sergeants and, at the last minute, ten privates from the 1st Artillery at Key West. Unfortunately, only one of these men had ever been to sea before, and none had ever seen a cable. Nevertheless, the Adria set sail on 29 May and arrived off Santiago on 1 June to begin destruction of the three cables believed to connect Cuba with the outside world. The task proved to be a dangerous one. The crew worked within the range of Spanish guns, to which the unarmed Adria could not reply. Moreover, the job proved more difficult than anticipated because of the deep waters and the fact that the cable became caught up on the coral sea bottom. Allen and his men did succeed in twice severing a cable but, as luck would have it, both cuts were made in the same line. After being exposed to repeated shelling, the captain and crew refused to continue working, forcing the abandonment of the operation. The War Department later cited Allen in general orders for his meritorious service in raising and severing the cables, and in 1925 he received the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions off Santiago.40 Allen then turned his attention to the second portion of his mission: establishing cable communication with the War Department in Washington. First he made arrangements to repair and use a French cable running from Guantanamo to New York via Haiti, which had been cut by the Navy. On 20 June he reported from shipboard the arrival of Maj. Gen. William R. Shafter and his V Army Corps off Santiago. The next day Allen opened a cable office near Guantanamo. From this point he could communicate with the War Department within five minutes. After Shafter's troops landed signal soldiers constructed land lines to complete the cir- [90] FIELD TELEPHONE STATION NO. 4 NEAR SAN JUAN HILL cuit between the front and Washington. Somewhat later, in mid-July, the Signal Corps laid its own cable between Guantanamo and Daiquiri to establish a connection independent of the French cable.41 If General Shafter had gotten his way, such electrical communication between the front and Washington would have been impossible. When his signal officer, Maj. Frank Greene, tried to persuade him to take signaling equipment to Cuba, Shafter replied that he only wanted soldiers with guns on their shoulders.42 Shafter's attitude notwithstanding, Greene and his signalmen accompanied the V Corps to Cuba and maintained flag communication between the ships of the fleet during the voyage. Despite the Signal Corps' ability to provide electrical communications, Shafter refused to allow the field telegraph train to be sent to Cuba. Once ashore, the folly of this decision became apparent, because the island's dense vegetation severely inhibited the use of visual signals. They were employed, however, to communicate with Sampson's squadron offshore. The Army thus would have been dependent on messengers to communicate between its commands had not Greely foreseen the difficulties. Before the Adria sailed, he had taken steps to obtain electrical equipment, insulated wire in particular, and loaded it aboard for Allen to use in Cuba. Since the Spanish enjoyed the benefits of both telephonic and telegraphic communications, the Americans would have been at a great disadvantage without them. Thanks to Greely's efforts, the War with Spain became the first conflict fought by the United States in which electrical communications played a predom- [91] WHITE HOUSE

COMMUNICATIONS CENTER DURING THE WAR WITH

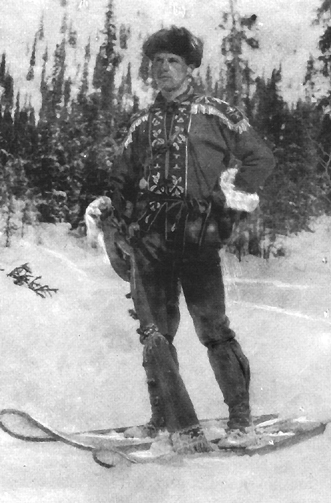

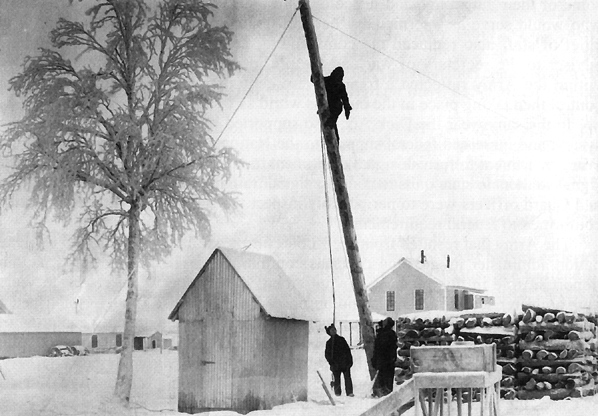

SPAIN. CAPTAIN inant role. For tactical purposes, the Signal Corps established telephone communication within camps and headquarters. For long-distance communication, it installed telegraph lines. While the telephone had the advantage of simpler operation, it did not, like the telegraph, provide a written record of all message traffic. Through the connections with the undersea cable, Shafter could communicate with Washington within twenty minutes even in the midst of battle. Like Secretary of War Stanton during the Civil War, President McKinley set up a war room next to his office in the White House with telegraphic connection to the front in Cuba. In addition, telephone lines linked McKinley with the War and Navy Departments, other key officials in Washington, and the port of embarkation at Tampa. A signal officer, Capt. Benjamin F. Montgomery, operated the White House communications center, known as the Telegraph and Cipher Bureau, a significant departure from Stanton's regime. Moreover, the executive departments also enjoyed telegraphic communication with Army and Navy officers in the field.43 Because the Signal Corps could not take its horses to Cuba due to the shortage of transport space, the men had to carry coils of wire into the field themselves or, when possible, use pack mules for that purpose. Even if telegraph wagons had been available, they would have been unable to travel over the rough terrain where unpaved trails often served as the only roads. Moreover, the jungle vegetation yielded few poles on which to string line. This fact made it all the [92] more important that Greely had sent insulated wire that could be laid directly on the ground or atop bushes. The Signal Corps' efforts under these difficult conditions enabled Shafter to communicate by telephone with his subordinate commanders throughout the campaign.44 Perhaps the Signal Corps' most famous (or infamous) incident in Cuba involved its use of the captive balloon during the battle of Santiago on 1 July. Because the jungle concealed both troop movements and terrain features, such as trails and streams, aerial reconnaissance could be of great advantage. The balloon saga began with its shipment in early April from Fort Logan to Fort Wadsworth in New York Harbor. There Greely intended it to be used to watch for the anticipated arrival of Cervera's squadron off the coast. The balloon became the responsibility of Lt. Joseph Maxfield, who had been relieved from duty as departmental signal officer in Chicago and transferred to New York. With his main task being the monitoring of international cable traffic into New York City, Maxfield had little time to spare for ballooning. When Greely finally received funds to purchase additional balloons and equipment after the war began, he directed Maxfield to procure them. As the Signal Corps had done in the past, Maxfield turned to French sources and purchased two balloons from the aeronaut A. Varicle. He was not able to complete them, however, in what proved to be the short time available. While Varicle labored, Maxfield shipped the old Fort Logan envelope and associated equipment to Tampa, where the V Corps awaited orders to embark. Maxfield, now a major in the Volunteer Signal Corps, arrived several days later and found his outfit scattered among various unmarked freight cars on sidings outside the city. Hastily locating the balloon and equipment, Maxfield and his recently organized detachment boarded ship just in time to sail with the V Corps. A second balloon detachment remained behind at Tampa.45 Once in Cuba, the balloon remained aboard ship for a week waiting to be unloaded. In the steaming hold, the varnished sides of the sphere stuck together. When Shafter finally called for a balloon reconnaissance before attacking the Spanish defenses outside Santiago, he denied Maxfield's request to unload the gas generator. Thus the balloon would have to depend on the gas brought along in storage cylinders-enough for only one inflation. Maxfield made the first ascent on 30 June, during which he noted terrain features and observed Cervera's ships in Santiago harbor. When the battle opened the next morning, the balloon was ready for action. Maxfield, accompanied by Lt. Col. George F. Derby, Shafter's engineer officer, ascended about a quarter of a mile to the rear of the American position at El Pozo. Derby, however, wished to get closer to the fighting and ordered that the balloon be moved toward the front. Maxfield objected, but he obeyed the command of his superior officer, and the balloon detachment hauled the sphere forward. Maxfield's concerns soon proved justified. The balloon floating overhead not only marked the location of the American troops but also gave the Spaniards an excellent target. Disaster followed. In the hands of an inexperienced crew, the guide ropes became entangled in the brush, completely immobilizing the craft. When the Spanish opened fire at [93] SIGNAL CORPS BALLOON AT SAN JUAN FORD the balloon, shrapnel and bullets rained down upon the troops below, resulting in numerous casualties. Maxfield and Derby escaped injury, but one member of the detachment received a wound in the foot. The balloon, meanwhile, was torn apart. Even if the holes could have been repaired, the signal detachment had no reserve gas available for reinflation. Despite the damaged balloon, the aerial reconnaissance had not been a total failure. The officers had observed the Spanish entrenchments on San Juan Hill and found them to be heavily defended. They then passed this information to the commanding general, with a recommendation to reopen artillery fire upon them. More important, Derby discovered a previously unknown trail through the woods that helped to speed the deployment of troops toward San Juan Hill.46 Although the Americans suffered heavy casualties during the fighting on 1 July, the Spanish had been more seriously harmed. The subsequent destruction of Cervera's squadron on 3 July in a desperate dash for freedom signaled the conclusion of the Santiago campaign. Shafter laid siege to the city and, after threatening to attack, forced the Spanish to surrender on 17 July. Following the end of the fighting in Cuba, troops under Maj. Gen. Nelson A. Miles undertook the capture of Puerto Rico, Spain's other major colony in the Caribbean. Of the six signal companies participating in this campaign, two bore the distinction of being among the Regular Army's first permanent signal units. They had been among the four companies, designated A through D, authorized by [94] General Greely on 27 July 1898. Companies A and D saw their first service in Puerto Rico. The other four signal companies that served there belonged to the volunteer corps. These six companies were organized into two provisional battalions, one commanded by Lt. Col. William A. Glassford and the other by Lt. Col. Samuel Reber, who later became Miles' son-in-law.47 Both Glassford and Reber held volunteer rank during the conflict. The invasion force landed on Puerto Rico's southern coast on 25 July and encountered only weak Spanish resistance as it moved toward the capital of San Juan. By 28 July Miles had captured Ponce, Puerto Rico's largest city. The Signal Corps promptly took charge of the city's telegraph office, which became the center of the Army's communication system on the island. Moreover, from Ponce two cable lines ran to the United States. Before abandoning the office, however, the Spanish had destroyed nearly all the equipment, and signal officers, short of repair material, had to improvise with the items at hand. Colonel Reber, for example, fashioned a telephone switchboard from a brass sugar kettle. Although the Spanish still held San Juan when the signing of a peace protocol ended the fighting on 12 August, the island, for all intents and purposes, was in American hands. By the time the Spanish evacuated Puerto Rico in mid-October the Signal Corps was operating nearly two hundred miles of lines there.48 Concurrent with operations in Cuba and Puerto Rico, the Army launched a third expedition to the Philippines, seeking to take advantage of an overwhelming naval victory. Upon the declaration of war, the Navy Department had ordered Commodore George Dewey, commander of the Asiatic Squadron, to sail from Hong Kong to Manila. With Spanish forces concentrated in the Caribbean, the Philippines lay vulnerable to attack. After winning control of Manila Bay by destroying the relatively weak Spanish squadron on 1 May, Dewey requested troops from the United States to capture the city. Meanwhile, Filipino insurgent forces led by Emilio Aguinaldo surrounded Manila, hoping to win Philippine independence from Spain with the assistance of the United States. The McKinley administration, however, chose not to ally with Aguinaldo's forces.49 Communication difficulties hampered Washington's ability to direct operations in the Philippines nearly ten thousand miles away. In fact, news of Dewey's victory did not reach Washington until 7 May. Dewey had cut Manila's cable to Hong Kong after the Spanish authorities refused his request to use it, and it did not return to operation until 22 August. In the interim, dispatches to the outside world traveled by ship to Hong Kong for transmission.50 As volunteer troops from western states as well as some Regular Army units gathered at San Francisco to sail for the Philippines, Maj. Gen. Wesley Merritt assumed command of what eventually became known as the VIII Army Corps. Recognizing the necessity of communications, Merritt requested signal soldiers, especially those who could speak Spanish, to accompany his troops. Since, as Greely commented, the Signal Corps was "fortunate in the linguistic acquirements of its officers," he could comply with Merritt's wishes.51 With little of the confusion and supply problems that plagued the Army at Tampa, the vanguard of [95] Merritt's force sailed from San Francisco on 25 May, stopped along the way to occupy Guam, and arrived in Manila on 30 June. The 1st Volunteer Signal Company was the first signal unit to land in the Philippines, arriving at Manila Bay on 31 July. The next day it began the construction of a telegraph line to connect Cavite, the base of supply, with the American troops stationed outside Manila. Working in heavy rains and excessive heat, the task was not an easy one. Difficulties notwithstanding, the company completed the job on 5 August. The 18th Volunteer Signal Company arrived on 24 August to assist with the establishment and maintenance of telegraph and telephone lines.52 Although the protocol signed on 12 August called for a cease-fire on all fronts, the troops in the Philippines did not receive the news for several days because of the severed cable. Thus, the armies fought the Battle of Manila on 13 August after peace had been declared. Like the Battle of New Orleans fought and won eighty-five years earlier by Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson after the formal conclusion of hostilities, the Battle of Manila occurred solely as a result of the slowness of communications. Because the Spanish could not successfully defend Manila, they made arrangements with the Americans to surrender after a token resistance. According to the agreement, the insurgents were not allowed to enter the city. All commanders had not been apprised of the arrangement, however, and hard fighting in several sectors resulted in some casualties. Having salvaged their honor, the Spanish finally surrendered, bringing the war to an end.53 During the Battle of Manila signal detachments served with each division and brigade commander, with one held in reserve. Another detachment ran an insulated wire along the beach as the troops advanced. Signalmen maintained communication with the Navy with flags, which they also used to direct naval gunfire against the Spanish positions. Within fifteen minutes after the troops seized the Spanish lines the Signal Corps ran its telegraph wires to the front. As Capt. Elmore A. McKenna, commander of the 1st Volunteer Signal Company, reported, "A red and a white flag of the Signal Corps were the first American emblems shown within the Spanish intrenchments, being there some minutes before the Spanish flag was pulled down and the American flag run up in its place."54 Among those cited for distinguished service during the battle was Sgt. George S. Gibbs, Jr., later a chief signal officer and father of the last man to bear that title, Maj. Gen. David P Gibbs.55 According to the terms of the peace treaty signed with Spain in December 1898, the United States acquired the islands of Puerto Rico and Guam. Spain further agreed to American occupation of Cuba and the annexation of the Philippines by the United States, for which Spain received $20 million in compensation. With the Hawaiian Islands, also annexed in 1898, the nation now held significant overseas territories. Despite the war's successful conclusion, the Army received much criticism, especially in regard to the health and diet of the troops in Cuba. The "embalmed beef" scandal is perhaps the best known. While few soldiers died of wounds, scores contracted typhoid, dysentery, yellow fever, and malaria. Many of the victims never [96] SIGNAL CORPS AT WORK DURING THE BATTLE OF MANILA, 13 AUGUST 1898 left the United States. Despite these problems, the Signal Corps escaped with a relatively low casualty rate, losing one officer in combat and only three officers and nineteen men to disease, about 2 percent of its total wartime strength of 1,300 officers and men. Four others died in accidents.56 Not only had the Signal Corps remained healthy, it had performed its communication functions well. The government's Dodge Commission, which investigated the conduct of the war, concluded that "the work accomplished by the Signal Corps was of great aid to the army in the field and very efficient in maintaining communication in all of the camps.57 The Signal Corps' aeronautical activities, however, did not fare as well. Although the Dodge Commission did not address the issue in its report to the president, the Corps' handling of the balloon received considerable rebuke, especially from members of units exposed to the fire it had drawn. One of these units was the 10th Cavalry, in which 1st Lt. John J. Pershing served as regimental quartermaster. Caught beneath the balloon, the 10th Cavalry received, in Pershing's words, "a veritable hail of shot and shell."58 According to Pershing, no one in the line knew the balloon's purpose, and the only intelligence furnished by its occupants was "that the Spanish were firing upon us-information which at that particular time was entirely superfluous."59 The novelist Stephen Crane, reporting on the war in Cuba, wrote of the balloon's "public death before the eyes of two armies."60 Aeronautics was still a largely unexplored area of Army operations, with no clear-cut doctrine yet developed for its use. Despite the mixed results in Cuba, the Signal Corps continued to explore the possibilities of airborne observation and reconnaissance in the postwar period. During the war the Signal Corps also experimented with another device-the camera. Although not an officially assigned function, photography fell within the [97] broad definition of communications. Beginning in 1894 photography had been taught as part of the signal course at Fort Riley, and in 1896 the Corps had published a Manual of Photography written by then 1st Lt. Samuel Reber. While serving in Puerto Rico, Reber used his skills to draw topographical maps based on photographs.61 Moreover, signal companies in all three campaigns carried cameras with which to document their operations. Improvements in photographic technology since the Civil War made combat photography an easier task than it had been for Mathew Brady. Smaller cameras using rolled film had replaced cumbersome glass plates; high-speed shutters and shorter exposure time made action photographs possible.62 Thus began one of the activities with which the Signal Corps is most closely identified-one that has made "Photo by the U.S. Army Signal Corps" a well-known phrase. The Corps displayed a collection of its wartime photos as part of its exhibit at the Pan-American Exposition held in Buffalo, New York, in the fall of 1901, and some of the photographs were reproduced in Greely's annual reports for 1898 and 1899.63 With the return to peace, the Signal Corps shrank to its prewar size. As the volunteer companies began to be mustered out, Greely expressed his appreciation for their service in lengthy orders published on 13 September 1898, in which he reviewed the contributions of the Corps in the three theaters of operation. Despite the hardships of the war, signalmen had "filled neither the guardhouse nor the hospital." In his words: "Battles may be fought and epidemics spread, but speedy communications must nevertheless be maintained."64 The acquisition of foreign territories by the United States carried with it increased duties and responsibilities for the Army. With the end of the war, soldiers could not return to business as usual, because the nation had become a major power. For the Signal Corps, its mission now included the administration of the communication systems in the Caribbean and the Pacific, in addition to its domestic duties. After the signing of the peace treaty with Spain, the United States sent troops to occupy Cuba until the Cubans established a government of their own. Maj. Gen. John R. Brooke commanded the American forces on the island and also served as military governor. Colonel Dunwoody became chief signal officer of the newly established Division of Cuba. Effective 1 January 1899, the Signal Corps took over the telegraph and telephone lines formerly operated by the Spanish government and assumed supervision of the private telephone and telegraph companies that had been granted licenses by Spain. First of all, Dunwoody arranged for the separation of the postal and telegraphic services, which had been combined in a single bureau. Then he turned his attention to repair and extension of the existing lines. The Spanish had built lines primarily in the western portion of the island, leaving two-thirds of Cuba without telegraph or telephone service. To enable General Brooke to communicate with his various subordinate commands and [98] posts, by April 1899 the Signal Corps had completed a 600-mile telegraph line from Havana to Santiago, or practically from one end of the island to the other. The Corps also built a new telephone system for the city of Havana and laid two cables in Havana Harbor. In addition to filling the Army's communication needs, the Signal Corps transmitted commercial business over its system. To meet the demand, the Corps constructed a second line between Havana and Santiago. With the mustering out of the Volunteer Signal Corps in April and May 1899, Dunwoody lost most of his men. To compensate for these losses, he hired Cuban workers to supplement his force and ultimately to replace Army personnel. When the Corps turned over operations to the Cuban government in 1902, it transferred nearly 3,500 miles of line that covered the entire island.65 In Puerto Rico, Major Glassford, who had reverted to his permanent rank after the war, directed signal operations. After the Spanish evacuated the island, the communication systems that had formerly been the province of the Spanish government or its licensees came under the Signal Corps' control. As in Cuba, the Signal Corps found most of the Spanish lines in a dilapidated state. It reconstructed and extended the system, but disaster struck when a hurricane hit the island in August 1899 and destroyed all the Signal Corps' work. Glassford began the task again, completed it, and in February 1901 the Signal Corps turned over the system to the new civil government of Puerto Rico.66 In the Philippines, meanwhile, a new war was brewing. Tensions had steadily increased between the Americans and the Filipino insurgent forces; their leader Aguinaldo had organized a provisional government for which he sought recognition. When it became clear that independence would not be forthcoming and that the United States would replace Spain as the ruler of the archipelago, Aguinaldo began an active resistance. On the night of 4 February 1899 fighting broke out around Manila, the beginning of what became known as the Philippine Insurrection. The next day a signal officer, 1st Lt. Charles E. Kilbourne, Jr. (son of the inventor of the outpost cable cart), distinguished himself at Paco Bridge, in a suburb of Manila. Under enemy fire he climbed a telegraph pole to repair a broken wire, reestablishing communication with the front. For this feat he became the third Signal Corpsman to win the Medal of Honor.67 American commissioners arrived in March primarily to act as a fact-finding body for President McKinley in preparation for the establishment of a civil government. On 4 April they issued a proclamation intended to convince the Filipinos of America's good intentions. It included a pledge to construct a communications network throughout the archipelago.68 The Signal Corps, under Maj. Richard E. Thompson and his successor Lt. Col. James Allen, became responsible for installing this system, which entailed laying cables between the principal islands. In addition to the permanent lines, the Corps ran temporary lines to accompany the troops in the field. Because the two volunteer signal companies still serving in the Philippines could not handle the expanded duties, a third company was formed out of personnel drawn from the two existing companies as well [99] as from other units. Each company operated with a division, forming detachments as needed for a variety of duties. The 18th Company, serving with Maj. Gen. Arthur MacArthur along the railroad from Manila to Dagupan, became railway dispatchers. As the volunteer signal units were gradually mustered out, Regular Army units replaced them. As in Cuba, the Signal Corps labored under adverse conditions. Lack of roads hindered the transportation of material and equipment; the terrain was often either jungle or swamp. To facilitate transportation, signalmen used carabao, or water buffalo, as pack animals. When possible, they employed either Filipino laborers who were friendly to the Americans or Chinese coolies as porters and linesmen. Wooden poles required constant repairs because they rotted in the intense heat or were destroyed by ants. The tropical climate, with its alternate wet and dry seasons, caused the soldiers physical discomfort and exposed them to indigenous diseases, such as malaria and amebic dysentery. The insurgents posed the greatest danger, however, incessantly sabotaging the lines and ambushing the soldiers who came to fix them. Armed escorts often accompanied the signal parties to provide protection, as the signalmen carried only revolvers.69 Perhaps the most ambitious job undertaken by the Signal Corps was the laying of submarine cables between the major islands. (Although a British firm, under concession from Spain, had already constructed cables between many of the islands, the Army needed its own system.) Other forms of communication were too slow, with mail sometimes taking two to four months to travel from one island to another. In some areas the Signal Corps conducted inter-island communication by heliograph and the newly adopted acetylene lantern. The transport Hooker, having been outfitted by the Quartermaster Department, arrived in the Philippines in June 1899 to begin cable-laying operations. While the Corps had received some experience with underwater cables in Cuba, it obtained assistance for the Philippine project from professional cable engineers. Unfortunately, on the way to Hong Kong to obtain coal, the Hooker was wrecked on a reef near Corregidor. Luckily, most of the cable and machinery were saved, and in April 1900 a second ship, the Romulus, began laying the recovered cable. With the arrival of the Burnside in December 1900, the Corps extended its system, laying over 1,300 miles of cable connecting the principal islands of the archipelago by June 1902.70 By early 1900 organized Filipino resistance had declined markedly. Despite American control of most of the provinces on Luzon, which was Aguinaldo's home and the center of the independence movement, guerrilla warfare continued and the pacification of the entire archipelago proceeded slowly. It was difficult for the Americans to tell friend from foe: The insurgents posed as civilians by day and took up arms at night. The hundreds of raids and ambushes mounted by the guerrillas cost the Americans dearly in casualties. With the capture of Aguinaldo in March 1901, guerrilla activity subsided but did not cease. Given the improving conditions in the islands, the Army shed its governmental responsibilities, and William Howard Taft became the civil governor in June 1901. Although sporadic [100] SIGNAL PARTY ON THE WAY TO MALOLOS, PHILIPPINES, 1899 fighting continued for several years thereafter, the United States declared the insurrection at an end on 4 July 1902.71 A gradual transfer of the Signal Corps' communications system to the civil government began in 1902. Initially the Army retained control of the entire cable system as well as those land lines needed for military purposes, but by 1907 the Corps had completed the transfer of over five thousand miles of land lines and cable, retaining only its system of post telephones and about one hundred and twenty-five miles of military land lines and cable.72 The acquisition of overseas territories made the laying of a Pacific cable a matter of urgent concern to the United States; without it, messages from the Philippines had to travel to the United States via China, India, Egypt, France, and England. President McKinley recommended its construction in his special message of 10 February 1899.73 Although Greely hoped that the Signal Corps would have a role in the project, the government instead granted permission to the Commercial Pacific Cable Company to construct a cable from San Francisco to China via Honolulu, Midway, Guam, and Luzon. The cable reached the Philippines in July 1903.74 America's growing involvement in Asian affairs received added impetus from the Boxer Rebellion of 1900. The United States had already espoused the Open Door policy, proclaiming the principle that all nations should share equally in trade with China. China's exploitation by foreign nations aroused resentment among young Chinese, who formed a secret society called the "Righteous Fists of Harmony" or Boxers. With the connivance of the Dowager Empress, the Boxers launched a bloody campaign to rid the country of foreigners who, fearing for their lives, took refuge in their legations in Peking. The legations, defended by [101] SIGNAL CORPS SOLDIERS IN CHINA DURING THE BOXER REBELLION, 1900 small numbers of soldiers and armed civilians, were soon besieged by a much larger force of Boxers and Chinese imperial troops. Because it already had substantial forces in the Philippines, the United States contributed a sizable contingent to an international relief force sent to China. A signal detachment of four officers and nineteen men under the command of Maj. George P Scriven accompanied the American troops on their march to Peking in August 1900.75 These men, in conjunction with British signal personnel, constructed a telegraph line to accompany the advance of the allied army from Tientsin to Peking, a distance of about ninety miles. The allies entered Peking on 14 August and saved the beleaguered legations. For several days the British-American telegraph line provided the only means of communication between the city and the outside world. During the period of occupation that followed, additional Signal Corpsmen arrived to construct a permanent telegraph line between Peking and Taku, on the coast, a distance of 122 miles. The occupation troops withdrew from China in September 1901, but a small American force remained to guard the Tientsin-Peking railway in accordance with the Boxer protocol.76 During the few years since the sinking of the Maine, the United States had firmly established itself as an active participant in world affairs. In the Philippines and China, the Army had demonstrated that it could operate success- [102] fully thousands of miles from home. By providing the necessary communications support, the Signal Corps contributed significantly to the nation's rise as a world power. Organization and Training, 1899-1903 The Signal Corps' greatly expanded duties required far more personnel than the ten officers and fifty enlisted men it had been authorized when the War with Spain began. The expansion of the Signal Corps by more than twenty times (from 60 to 1,300 officers and men) for wartime purposes seemingly convinced Army and congressional leaders that the Corps needed a larger peacetime force in the new electrical age. To meet the Army's current manpower demands caused by occupation duties and continued fighting in the Philippines, Congress on 2 March 1899 temporarily increased the size of the regular and volunteer forces. For the Signal Corps, Congress provided 720 enlisted men. In separate legislation, Congress authorized the president to retain in service or appoint 31 volunteer Signal Corps officers to supplement its complement of 10 regular officers. For the immediate future, this action helped to alleviate the Corps' critical need for trained officers.77 Over the next few years the Signal Corps underwent numerous reorganizations. By July 1899 all of the volunteer signal companies had been mustered out except those in the Philippines. Because the conditions of service were so poor and the length of overseas tours so long (from two to four years), especially in the Philippines, few volunteer signal soldiers chose to transfer to the Regulars. The Corps needed, therefore, a sizable pool of new personnel to provide replacements for these overworked soldiers. In 1900 President McKinley increased the enlisted strength of the Signal Corps to 800 and Congress, by joint resolution, authorized the appointment for one year of ten additional volunteer officers.78 When Congress legislated a permanent expansion of the Army in February 1901, however, it reduced the Signal Corps' enlisted strength to 760, causing the discharge or reduction in rank of many men who had served with distinction in China and the Philippines.79 In the next year the lawmakers reversed themselves, boosting the branch's enlisted strength in June 1902 once more to a total of 810, adding 50 sergeants. Subsequent legislation allowed the temporary addition of another 50 sergeants for as long as deemed necessary by the secretary of war or the president.80 As for the officer ranks, the February 1901 legislation provided some relief by setting the Signal Corps' permanent commissioned strength at 35 (a brigadier general, a colonel, a lieutenant colonel, 4 majors, 14 captains, and 14 first lieutenants). The law also authorized the retention "only for the period when their services may be absolutely necessary" of 10 volunteer officers: 5 first lieutenants and 5 second lieutenants. Chief Signal Officer Greely, however, wanted more than such stopgap measures. Not only did Signal Corps officers have increasingly complex duties to perform, but the arduous service expected of them in the trop- [103] ics placed many on the sick and disabled lists.81 Moreover, the percentage of officers (17.1) in relation to the total strength of the branch ranked far below that of the other staff corps (the proportion of officers in the Medical Department, which had the next lowest percentage, was 24.9).82 In March 1903 Congress responded to the Signal Corps' needs by authorizing the addition of 11 commissioned officers (1 lieutenant colonel, 2 majors, 4 captains, and 4 first lieutenants), bringing the total to 46.83 Meanwhile, signal training also underwent some changes, as Fort Myer once again became the home of the Signal Corps in 1899.84 The branch returned to centralized training and discontinued the schools at Fort Logan, the Presidio of San Francisco, and San Antonio, Texas. Individual signal instruction at the departmental level, while still mandated by Army regulations, could not be relied upon to produce skilled signal soldiers, as previous experience had demonstrated. In fact, the War Department had made matters worse by amending the regulations in 1899 to require only such instruction as the departmental commanders "deemed necessary for the public service," rather than the previously required two months' worth.85 Moreover, the Corps had been unable to furnish a signal officer to each department to oversee the instruction. Recruits sent to Fort Myer received training in telegraphy, telephony, line repair, and visual signaling. While six months of training was preferable, the demand for signal soldiers in the field limited it to as few as four months. Once telegraph operators achieved a competency of twenty words per minute, they served as assistants on the military telegraph lines in preparation for duty overseas. Officer-level instruction was also conducted on a limited basis. In addition to its training function, the post became a depot for supplies being returned from the various Signal Corps posts, domestic and overseas. With the closing of the signal school at Fort Logan, Fort Myer also became the new home of the Signal Corps' balloon operations. In 1900 Congress appropriated funds to build a balloon house on the post, which was completed early the following year.86 Congress did not, however, appropriate additional funds to support aeronautical activities. In particular, Fort Myer lacked a gas generating plant, an essential facility for successful ballooning. Despite the continuing shortage of resources, both in personnel and equipment, the Signal Corps formed a balloon detachment at Fort Myer in 1902, and it participated in the Army maneuvers held in Connecticut that year.87 Although the Signal Corps remained earthbound for lack of a gas plant, the year 1903 witnessed several significant events in aeronautical history. In October and December, Samuel P Langley made two unsuccessful attempts to launch his so-called Aerodrome, a machine that resembled a giant dragonfly. A few days after his second failure, the Wright brothers flew successfully at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, on 17 December. Their achievement remained virtually unknown to the world at large for several years because the Wrights avoided publicity pending the receipt of a patent for their airplane. Nevertheless, above the windswept dunes of the Outer Banks, a new age of flight had begun. [104] New Frontiers: Alaska and the Dawn of the Electrical Age While the military potential of aeronautics was yet to be discovered, the value of electricity to Army communications had been clearly demonstrated during the War with Spain. In 1902 the Signal Corps recognized its increasing importance by establishing an Electrical Division, headed by Capt. Edgar Russel, to take responsibility for the field of electrical signaling, exclusive of the military telegraph lines. In the division's laboratory and carpentry shop, the construction and testing of improved telephones and other devices took place. The Corps also undertook the installation of electric lighting at Army posts. Because not enough signal soldiers were available to fully staff the division, the Corps hired civilian electrical engineers.88 While the telegraph and the telephone had dramatically improved communications, a new technology began to make its appearance-wireless telegraphy, or radio, as it became known. This new form of communication had been demonstrated in Europe by Guglielmo Marconi, an Italian inventor and entrepreneur. Although others had discovered the principles of radio, Marconi successfully exploited its commercial potential. He brought his system to the United States in 1899, where he used it to report the results of the America's Cup yacht races held that fall.89 Radio had many advantages over the visual, wire, and cable systems then in use. For example, it was not limited by hindrances to visibility such as darkness or fog. Moreover, with the Army and the world at large becoming more mobile through the introduction of motorized transport, radio had the ability to go where wires and cables could not. Radio had particular application for communication from ship to ship and between ship and shore. Its availability during the War with Spain might have dispelled some of the confusion between Sampson and Schley concerning Santiago. Still, in the early twentieth century, "radio" simply meant the transmission of Morse dots and dashes through the air. The technology for the wireless transmission of the human voice and music had not yet been developed. The Signal Corps began its investigations into radio even before Marconi's arrival in America. To lead its research efforts, the Corps had its own electrical expert, 1st Lt. George O. Squier. After graduating from West Point in 1887, Squier had attended the Johns Hopkins University and received a doctorate in electrical engineering in 1893, becoming one of the first soldiers to earn this advanced degree. He selected as his dissertation topic "Electro-Chemical Effects Due to Magnetization."90 Originally commissioned as an artillery officer, Squier served in the Volunteer Signal Corps during the War with Spain and transferred to the Signal Corps of the Regular Army in February 1899. Assisted by Lt. Col. James Allen, a signal officer with considerable experience in electrical communication, Squier developed a wireless system that was first used in April 1899 to communicate between Fire Island and the Fire Island lightship off Long Island, a distance of about twelve miles. With this success, the Signal Corps next established a wireless connection between Governors Island and Fort Hamilton in New [105] York Harbor, followed by Fort Mason and Alcatraz in San Francisco. In May 1899 Squier traveled to London to study under Marconi.91 While wireless still had many "bugs" (it could be easily intercepted by the enemy, for example), the Signal Corps had taken the initial steps toward launching this new form of communication. If wireless had been further along the road to perfection, it would have been ideally suited for the Signal Corps' next major project, the installation of a military communications system for Alaska. The discovery of gold in Alaska along the Yukon River and at Nome in the late 1890s and the consequent rush of fortune seekers created the need for a significant Army presence as a police force in that untamed wilderness. In 1897 rumors of starvation among the miners led Secretary of War Russell A. Alger to prepare a relief expedition to prevent a tragedy. Besides foodstuffs, the War Department purchased 500 Norwegian reindeer to carry the supplies over the frozen terrain. Just before the relief force departed from Portland, Oregon, reports from Alaska indicated that the rumors of famine had been unfounded. When Canadian and American authorities confirmed that no danger existed, Alger canceled the expedition. The whole affair had highlighted, however, the problems to be faced in communicating with the nation's northernmost territory.92 In 1899 the War Department created the Department of Alaska, with headquarters at Fort St. Michael on Norton Sound. To establish communication links, Congress in 1900 authorized construction of the Washington-Alaska Military Cable and Telegraph System (WAMCATS) and assigned its supervision to the Signal Corps. The new lines would connect the nation's capital to the military posts and the posts to one another as well as serve the commercial telegraph needs of the territory.93 The Alaskan system, in fact, became the last in the chain of frontier telegraph lines to be built by the Signal Corps. After enduring service in the tropical climes of the Caribbean and the Philippines, signal soldiers now faced the opposite extreme. As in the tropics, the environment itself would present one of the most formidable obstacles to progress. In Alaska, featureless tundra and treacherous muskeg swamps replaced jungles as natural obstacles, while the accompanying temperatures plunged as low as -72 degrees Fahrenheit. In the summer when the weather moderated, hordes of mosquitoes plagued the linesmen, and forest fires posed an additional hazard. Funds from the initial appropriation of $450,550 became available in June 1900, and Greely hurried to secure supplies so that work could begin before winter. The first detachment of men from Company D, Signal Corps, under 1st Lt. George C. Burnell, landed at Port Valdez on 9 July. By August, when most of the equipment had finally arrived from the United States, construction parties had taken the field. Difficulties in finding suitable routes for the line and the onset of winter slowed the rate of progress, and Greely expressed concern that the system would not be completed before Congress cut off the money. The chief signal officer, who had himself strung thousands of miles of wire early in his career, could apply his considerable experience to the task at hand. [106] CAPTAIN MITCHELL IN ALASKA From his Arctic service, Greely knew only too well the rigors under which his men would be laboring. Alaska was virtually unexplored and uninhabited, with a climate to test the mettle of the most sturdy soldier. Luckily the Signal Corps had such a man in 1st Lt. William ("Billy") Mitchell. Mitchell, who later became famous as an outspoken advocate of air power, joined the Volunteer Signal Corps in 1898 and served in Cuba and the Philippines. In the summer of 1901 Greely sent him to investigate the conditions in Alaska. After traveling extensively throughout the territory, Mitchell submitted his report to the chief signal officer. To expedite the construction project, Mitchell suggested that work continue throughout the winter when supplies could be easily transported over the ice and snow and cached for work in the warmer months. In the fall of 1901 Mitchell returned to Alaska to help build the lines, later writing an account of his observations and travails that makes fascinating reading.94 Greely assigned to Mitchell the job of surveying and laying the telegraph line south from Eagle City (site of Fort Egbert) on the Yukon River to meet the line northward from Valdez (Fort Liscum) being built by Burnell, now a captain. The total length of this line measured approximately four hundred and twenty miles. While surveying the route, Mitchell nearly died when he and his sled broke through the ice of a frozen river with the air temperature at about sixty degrees below zero. Fortunately, his lead dog gained a foothold on the ice and pulled the lieutenant to safety.95 After completing this job in August 1902, Mitchell constructed the line westward from Eagle toward Fairbanks to connect with the wire run eastward from St. Michael by 1st Lt. George S. Gibbs. When he finished his Alaskan duties in the summer of 1903, Mitchell and his sled dogs had traveled more than 2,000 miles.96 Infantry and artillery troops posted to Alaska performed much of the line construction, while signal soldiers handled the technical aspects. Telegraph main- [107] tenance stations were established every forty miles and were manned by three soldiers-one signalman with two infantrymen as assistants. Some men found this lonely vigil more than they could take, especially during the long, dark Alaskan winters, and a few desperate souls committed suicide.97 As originally planned, the first Alaskan lines made no connections outside of the territory. To establish telegraphic communication with the United States it would be necessary to connect the Alaskan lines with those of Canada. Therefore, Greely arranged a meeting with his personal friend, Canadian Premier Sir Wilfrid Laurier, to request permission for the Army to connect its wires to the Canadian lines terminating at Dawson in the Yukon Territory. Laurier agreed to the proposal, and by the spring of 1901 telegraphic messages from Alaska traveled via Canada to the United States.98 To provide an "all-American" communication system, the final portion to be constructed consisted of cables connecting southeastern Alaska to the continental United States. The Burnside, the Army's only cable ship, was transferred from the Philippines to begin the job in the summer of 1903. Colonel Allen and Captain Russel supervised the installation. During the winter, while operations were suspended for several months, the buoyed sea end of the cable was washed away, and 600 miles of cable had to be recovered and put back in place. By October 1904 Allen and Russel had laid over 2,000 miles of cable from Seattle to Valdez to include a section between Sitka and Skagway.99 Because the movement of ice floes prevented a cable from being maintained across the 107 miles of Norton Sound, the Signal Corps established a wireless link across its waters in 1904.100 This project, successfully carried out by Capt. Leonard D. Wildman after a private contractor had failed, finally made communication possible between St. Michael and Nome. Because radio was still in its infancy and generally reliable only over short distances, the success at Norton Sound was significant; Greely declared it to be "the longest wireless section of any commercial telegraph system in the world."101 Upon completion, the Washington-Alaska Military Cable and Telegraph System comprised 2,079 miles of cable, 1,439 miles of land lines, and the wireless system of 107 miles, for a total mileage of 3,625.102 It had proven to be an enormous undertaking, and an accomplishment of which the Signal Corps could be justifiably proud.103 The early years of the twentieth century marked an important transitional period for both the nation and the Army. In the War Department, Secretary of War Elihu Root effected a major reorganization in 1903 with the establishment of the General Staff, headed by a chief of staff. Root recognized, as had the Dodge Commission, that the Army, with its global responsibilities, could not afford to repeat the chaos it had experienced during the mobilization for the War with Spain. The General Staff would conduct overall military planning for the Army and coordinate the activities of its bureaus. Consequently, the bureau chiefs lost [108] TELEGRAPH REPAIR WORD AT FORT

GIBBON, ALASKA;

below, INTERIOR OF FORT

GIBBON [109] some of their autonomy, and henceforth they would report to the chief of staff, who would serve as intermediary between them and the secretary of war. The chief of staff also replaced the commanding general as the principal military adviser to the secretary of war and the president. This consolidation of power within the Army reflected a trend toward centralization of administration and control then taking place in the business world as well.104 In the same year the Dick Act, also supported by Root, reformed the militia system and increased federal support to the National Guard. The act allowed the War Department to furnish signal equipment to Guard units and to detail Regular signal soldiers to state units to conduct signal training. Furthermore, both Regular and Guard officers were to periodically inspect the state units to ensure that they conformed to federal requirements.105 The Army that resulted from the Root reforms was better prepared to help the nation administer its growing overseas commitments. The Signal Corps had an important role in this process. Having emerged from the weather service years with a clearer sense of mission and purpose, the branch had finally established a place for itself within the Army's structure. Adapting to the ongoing evolution of communications technology, the Corps rendered diverse and arduous service in far-flung areas of the globe, in the words of Chief Signal Officer Greely, "whether in isolated Alaska, storm-stricken Porto Rico, the yellow fever districts of Cuba, the arid plains of China, or among the Philippine insurgents."106 Even greater challenges lay ahead [110] Return to Table of Contents

|